Restaurant and school closures have led to a glut of dairy intended for the food service industry. Turning it into retail products is no easy feat.

On Monday, Mary Baus, co-owner of Tower View Acres dairy farm in Mt. Calvary, Wisconsin, was urged by her main buyer, a cheese factory, to decrease production by 20 percent. Typically, the factory can sell its extra milk to other processors. But in the past weeks, demand has all but evaporated. Now, farmers like Baus are being asked to scale back supply, sometimes in drastic ways.

Since the first Covid-19 outbreaks emerged in the U.S., stay-at-home orders have blanketed all but seven states. Consequently, most restaurants have shut down or switched to operating on a stripped-down, delivery basis. Approximately 120,000 public and private schools have closed their doors, with some reducing food service to grab-and-go options and others axing it altogether. These changes have significantly lowered demand for dairy products, including fluid milk, cheese, and butter, in the food service sector.

But from a grocery shopper’s perspective, the idea of a dairy surplus may come as a surprise, particularly when many stores have instituted limits on milk purchases due to high demand. The discrepancy is rooted in the fact that there are two distinct dairy supply chains, one dedicated to food service and another for retail. And crossover isn’t easy, leading to the dire quandaries many dairy farmers are being forced to face right now—up to and including, “Should I dump my unsold milk?”

The issue is, processors who primarily supply to food service buyers simply don’t have the infrastructure to quickly pivot to retail. “If you have a factory that was set up to produce sour cream to sell at Mexican restaurants, you can’t just decide that tomorrow you’re gonna produce ice cream and send it to the grocery store,” says Christopher Wolf, a Cornell economist who specializes in dairy.

Additionally, processors that do supply to retailers typically run a tight ship, meaning that they don’t have a lot of surplus equipment to absorb unexpected surges in supply or demand.

“The dairy supply chain is optimized for efficiency,” says Marin Bozic, an ag economist at the University of Minnesota. “Everybody tries to keep their plants running at full capacity, which also means that they don’t have a little spare capacity or spare packaging lying around.”

“If we reduce supply by reducing the herd size, then later when more milk is needed, we won’t have enough animals, and the milk prices will be really high.”

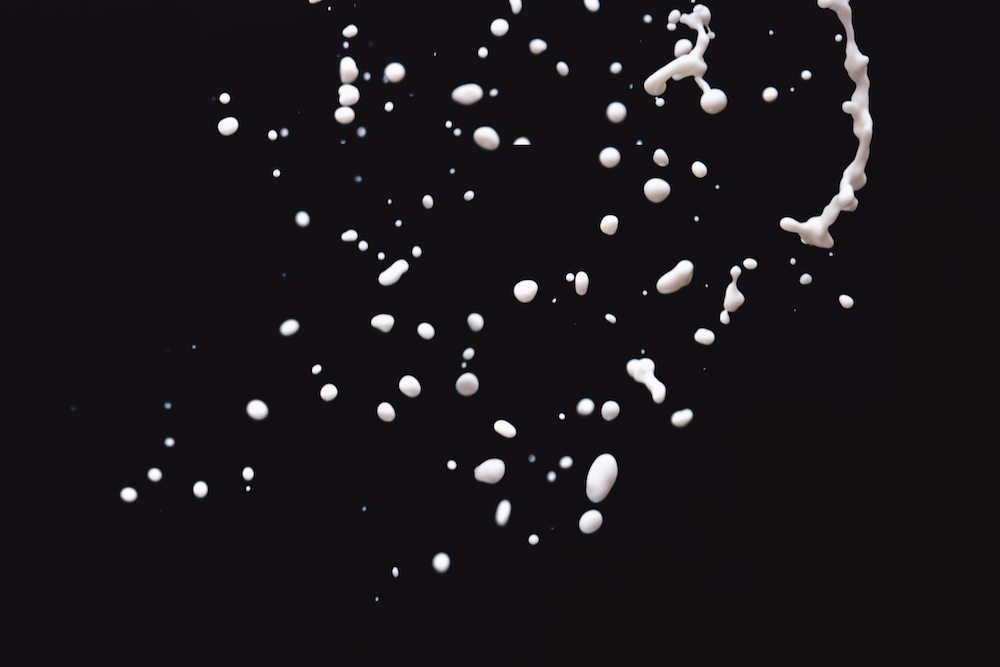

As a result, some producers have had to take extreme measures to correct for the unprecedented oversupply. In the biggest dairy-producing states, from Vermont to New York to Wisconsin, farmers are reportedly dumping tons of raw milk literally down the drain. Dairy Farmers of America (DFA), the country’s largest cooperative of milk farmers, has asked some members to do the same.

“[In] some regions, where there is no viable market for milk right now, we’ve had to ask some farms to dispose of raw milk, as a last resort,” said Kristen Coady, senior vice president, corporate affairs at DFA, in an emailed statement.

Other cooperatives, like Organic Valley and the Northwest Dairy Association, haven’t resorted to such extreme measures. Nor has Baus, who tells me she can cut production back by feeding her herd less protein. However, she’s worried that she won’t be able to make a profit this year, because many of her costs—like insurance, repairs, and loan payments—are fixed. “It’s going to be very tight,” she says. “We’re going to work for nothing.”

“But we’re talking about a level of dumping that is not common at all. There’s a lot of farmers that are experiencing dumping milk for the first time in their 30- or 40-year careers.”

For many farmers, milk dumping can feel like an insult to injury: The industry has struggled in recent years due to declining consumption, consolidation, and low prices.

But just how much the industry should reorient processing systems away from food service and toward retail depends on a major unknown: How long the pandemic will keep schools out and restaurants shut down. “Part of the question is: How long is this disruption going to be?” Wolf says. “Is it worth it to kind of try to redo the supply chain? How much should we be changing this?”

As long as the answers to those questions remain up in the air, dumping may be the quickest, if painful, way to skim the fat.

Milk dumping isn’t a novel practice, but the scale of dumping right now is, according to University of Tennessee ag economist and extension professor Andrew Griffith.

“It’s not that [dumping] hasn’t occurred from farm to farm,” he says. For example, when poor weather conditions prevent a processor from picking up milk, or when supply unexpectedly goes bad. In 2016, for example, a glut forced farmers to dump 43 million pounds. “But we’re talking about a level of dumping that is not common at all. There’s a lot of farmers that are experiencing dumping milk for the first time in their 30- or 40-year careers.”

For farmers, the coronavirus pandemic couldn’t have hit at a worse time. Spring is known as the “flush” season in the industry, a period when production is at its peak. Cows can’t simply go unmilked—not if farmers want them to keep producing once the pandemic is over.

Milk prices are dropping, in some cases to levels where farmers aren’t sure if they can break even.

“If we reduce supply by reducing the herd size, then later when more milk is needed, we won’t have enough animals, and the milk prices will be really high,” Bozic says.

While retail-level purchases of milk have spiked, driven by an increase in shoppers and some panic-induced hoarders, it’s not necessarily enough to fill the gap left by schools and restaurants.

The National Milk Producers Federation (NMPF), an industry lobby, estimates that supply exceeds need by more than 10 percent right now. As a result, milk prices are dropping, in some cases to levels where farmers aren’t sure if they can break even. That’s the position that dairy farmer Tina Hinchley, of Hinchley’s Dairy Farm in Cambridge, Wisconsin, has found herself in.

“This is tough,” Hinchley says in a phone interview. Hinchley is a DFA member, but she hasn’t been asked to dump milk yet. In past years, Hinchley has been able to balance the books with revenue from other crops like corn. But the coronavirus pandemic has hit that industry hard as well: Demand for corn-based fuel is the lowest it’s been in a decade.

When a cooperative like DFA instructs select farmers to dump, the loss ultimately gets split among all members.

For NMPF’s part, the organization is asking the federal government to financially incentivize farmers to produce less milk—in other words, to give them a reason to scale back rather than double down on production.

On the slightly bright side, when producers dump milk, there are a few mechanisms that protect them from shouldering the loss alone. Late last month, the Department of Agriculture announced it would allow producers who participate in federal milk marketing orders to get paid for milk that had to get dumped due to impacts of Covid-19. Additionally, when a cooperative like DFA instructs select farmers to dump, the loss ultimately gets split among all members.

“[It] will just take the average amount of revenue that [its members] had and [it] will have to spread it across all the milk, including the dumped milk,” says Wolf. “So everybody will get paid a little bit less. So it’s kind of sharing the pain.”