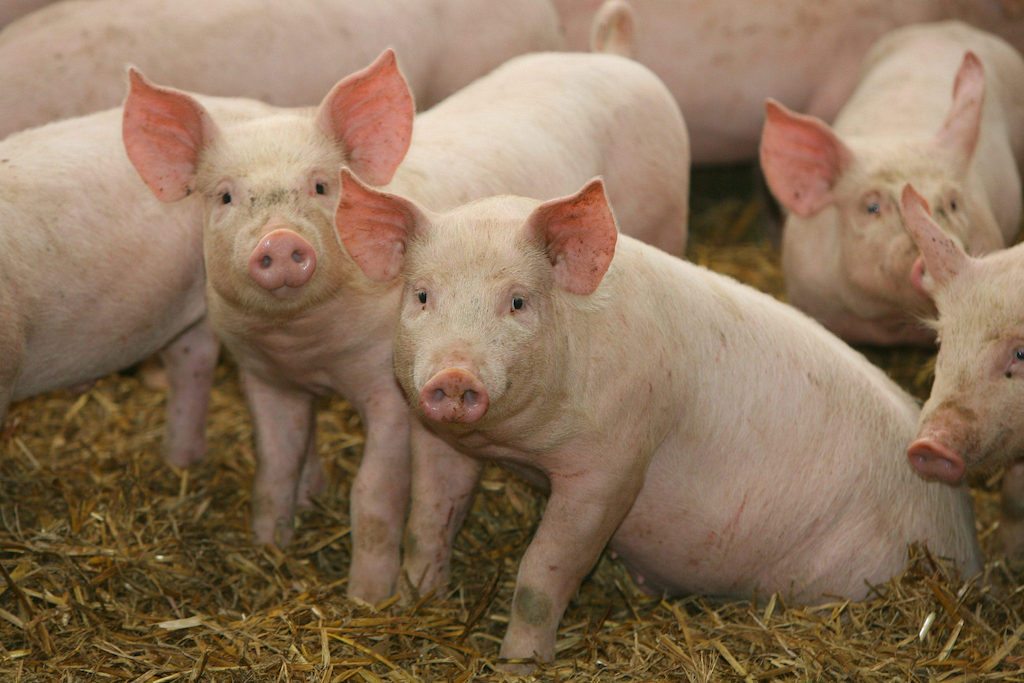

In January of 2009, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finalized a rule exempting all farms from reporting air releases of hazardous substances to the federal government. It was an exemption granted by the outgoing Bush administration in 2008 that environmental groups said allowed concentrated animal feeding operations (also known as CAFOs) to skirt accountability for their emissions of toxic and potentially lethal ammonia, hydrogen sulfide, and manure fumes.

For its part, EPA said at the time that the rule was “consistent with the Agency’s goal to reduce reporting burden, particularly considering that Federal, State or local response officials are unlikely to respond to notifications of air releases of hazardous substances from animal waste at farms.”

Just after the rule was finalized, environmental advocacy groups including Waterkeeper Alliance and Sierra Club filed a lawsuit with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, arguing that the rule should be abolished entirely. Pork producers were also upset about the rule and filed a lawsuit, but for an entirely different reason. The National Pork Producers Council contended that EPA hadn’t provided adequate guidance for farmers on compliance and didn’t have a system in place to handle the volume of reports. It also alleged that EPA had deliberately undermined the ability of farmers to comply by issuing its guidance on the last business day before the deadline for filing emissions reports. The two lawsuits were later folded into one.

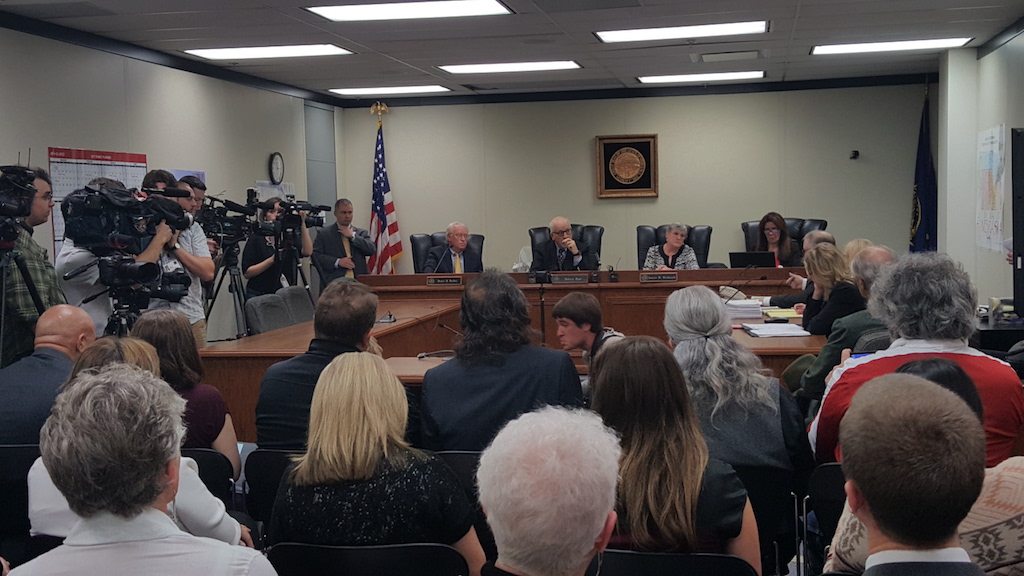

What followed was years (and years) of procedural delays, as EPA stalled and attorneys from non-profit environmental law organization Earthjustice fought to roll the rule back. Finally, in December of 2016, Jonathan Smith, associate attorney at Earthjustice, went to court on behalf of communities suffering from various health issues they said were related to exposure to emissions.

In a blog post dated December 12, 2016—the same day he went before the Court—Smith wrote: “While other industrial facilities are required by law to report their toxic releases, tens of thousands of livestock factories have essentially been given a free pass by the EPA. The exemption stymies local efforts to clean up pollution and puts the health of local people at risk. It’s also unlawful, as I will argue in court.”

This week, Smith and other environmental groups have cause to celebrate. The District of Columbia Court of Appeals on Tuesday handed down a decision that vacates the rule.

In a post published on Wednesday, Smith said that the public has regained its right to information. “Because of yesterday’s ruling, the government and the public will again know about releases of hazardous substances like ammonia that can affect our health and safety. Government agencies can use this data to better protect the public from toxic emissions and respond to emergencies. And the public can use these reports to avoid health threats in their communities from livestock pollution.”

But the final word on the value of emissions reports to the EPA belongs to Judge Stephen F. Williams, who in his opinion states: “We find that those reports aren’t nearly as useless as the EPA makes them out to be.”