Graphic by Alice Heyeh | New York Public Library/Smithsonian/iStock

From small, incremental additions and subtractions to complete menu overhauls, the pandemic has prompted chefs around the country to rethink what they serve.

Earlier this year, on a brisk May evening at the El Sereno Night Market in East Los Angeles, dozens of people lined up outside the tent where Elvia Huerta and Alex Garcia of the “metal taco” duo called Evil Cooks were selling, among other dishes, tacos and tortas filled to bursting with pork basted in an intensely fragrant, ink-black paste of charred chiles and spices.

Evil Cooks

The Poseidon is an eye-catching octopus dish that is marinated in a Yucatan-style recaudo negro chile paste and spit-roasted on a trompo. The dish, originally inspired by the ‘octopus al pastor’ taco made by Evil Cooks’ friend, Dallas taco chef Regino Rojas, has become a staple of Evil Cooks’ pandemic-era restaurant menu.

On this night, their popular “black al pastor” was upstaged by a newer menu item—a $5 octopus taco called The Poseidon. The dish became an instant hit among the city’s taco cognoscenti when it was added to the menu earlier this year, thanks in part to its laborious and uncommonly dramatic preparation—the brawny, Medusa-like headdress of chile-rubbed, pineapple-garnished octopus is skewered on a trompo and slow-roasted until muscle and flesh become preternaturally tender.

Because the dish is expensive and time-consuming to make, the Poseidon is not a big profit-maker, Huerta said. But it generates social media interest, drives foot traffic, and its eye-catching preparation has bolstered Evil Cooks’ reputation as one of Los Angeles’ most distinctive and exciting taco purveyors.

The Poseidon (inspired by the ‘octopus al pastor’ taco made by Evil Cooks’ friend, Dallas taco chef Regino Rojas) is a “calling card,” said Huerta, the culinary embodiment of Evil Cooks’ basic operating philosophy: “Go big or go home.”

In March of 2020, when the pandemic shut down the public markets and pop-up venues where they made a living, Huerta and Garcia went very big—they erected a semi-permanent food stand in front of their home in El Sereno, and expanded the menu with new items. At one point, Garcia recalls, there were three trompos in front of their home, simultaneously churning out lushly marinated taco meats. And it worked—the bigger menu generated new customers, which compelled them to extend their hours at the food stand.

Twenty miles across town in Santa Monica, Bryant Ng took a different approach to pandemic-proofing the menu at Cassia, the French-Southeast Asian brasserie that he opened with his wife and business partner, Kim Luu-Ng, in 2015 (the restaurant is part of the Santa Monica-based Rustic Canyon restaurant group).

In the chaotic early months of the shutdown, Ng and his team whittled down Cassia’s menu to “core” items that translated well into take-out and curbside pick-up. Seafood was the first thing to leave the menu, Ng recalls, and the restaurant’s raw bar and wood-fired grill were temporarily closed to reduce costs. Like many restaurants, Cassia added a carryout family meal option that proved so popular it has stayed on the menu.

“Most restaurants of this size, you try to make incremental changes. You can’t make drastic changes to the menu.”

Making any kind of change to a large and well-established brick-and mortar restaurant such as Cassia is like trying to turn an aircraft carrier around in the middle of the storm—it requires a conservative approach, Ng told me earlier this year.

“Most restaurants of this size, you try to make incremental changes. You can’t make drastic changes to the menu,” he said.

Evil Cooks and Cassia, two restaurants rarely mentioned in the same breath, share one basic attribute, at least—both navigated the extreme turbulence of the coronavirus pandemic by reevaluating and constantly adapting their menus at every stage of the pandemic. And they’re hardly alone—in a January 2021 survey by the National Restaurant Association, 63 percent of fine-dining restaurants operators, and half of family and fast-casual operators reported changing menus (namely, by streamlining the number of menu options).

Amid constantly changing health mandates and dining restrictions, supply-chain breakdowns, surging inflation and widespread worker shortages, the restaurant menu is one of the few variables under an owner’s control. As such, it plays a central role in shaping a restaurant’s destiny and form.

If you peel back the cultural and aesthetic attributes of most restaurant menus, what can they tell us about the economic and sociocultural forces that so far have shuttered an estimated 10 percent of all U.S. restaurants? And what can they tell us about American dining, if anything, in the months and years ahead?

One thing the pandemic laid bare is that restaurant menu prices rarely reflect the true cost of doing business.

At San Francisco’s Che Fico, the California-Italian restaurant that chef and restaurateur David Nayfeld operates with his business partner, Matt Brewer, a new 10 percent “dining in charge” is printed prominently at the top of the menu.

“Dining in” surcharges are not yet common on most menus, but higher prices are forecasted for both independent and chain restaurants, who are raising prices to mitigate the rising costs of doing business.

The surcharge helps pay for higher wages and benefits for Che Fico employees, Nayfeld said. But it also represents the “true cost of dining inside of a restaurant.”

Higher restaurant menu pricing is a corrective to an industry built on bad math, he said. “There has been a decades-long fear of telling the consumer that they need to pay more for food.”

“Hospitality brands are about generosity of spirit. We’re about making guests feel welcome, like they can have anything their imagination can come up with,” he said. “But for the past several decades, we’ve done that at the expense of the labor force.”

“Dining in” surcharges are not yet common on most menus, but higher prices are forecasted for both independent and chain restaurants, who are raising prices to mitigate the rising costs of doing business. As prices rise, consumers will have to adjust expectations about what is reasonable or not, for the privilege of eating inside restaurants.

The pandemic is also making menus smaller and less complicated. Restaurants of all sizes have drastically reduced their menu offerings, including fast-food and fast-casual chains; the pancake chain IHOP downsized from 12-pages to a two-page menu, and McDonald’s famously axed its all-day breakfast menu. More than 60 percent of restaurateurs surveyed by the National Restaurant Association said they planned to keep smaller menus, which are less costly overall to execute.

Menus have changed in substance, as well: the transition to carry-out and delivery service forced traditional sit-down restaurants—steakhouses and fine-dining establishments, for example—to reconsider dishes that are too unwieldy, complicated or otherwise unsuitable for take-out.

IHOP downsized from 12-pages to a two-page menu during the pandemic.

“We did a fair amount of seafood that didn’t feel like it would translate well as carryout. Those things worked their way off the menu,” recalls Austin Carson, chef and co-owner of Restaurant Olivia in Denver, who opened the fine-dining Italian restaurant with partners Heather Morrison and Ty Leon in January of 2020.

Two months after Restaurant Olivia’s opening date, the pandemic shut down indoor dining in Denver. Since then, the menu has been put through the pandemic gauntlet—depending on what stage of the pandemic you’re talking about, the restaurant shape-shifted from a take-out only restaurant to a reservations-please, prix-fixe destination.

Take-out and delivery menus emerged as the definitive feature of pandemic-era dining, and it’s possible that the speed and convenience of eating at home will make take-out a permanent fixture of many people’s lives. According to a report from the restaurant software company Paytronix, online orders tripled over the course of the pandemic; 65 percent of those orders were made by customers with no previous experience using online ordering platforms, a staggering rate of adoption that points to the staying power of a trend.

Eating at home, alone or among family, is hardly new. But the rise of online ordering, coupled with pandemic-era rules around physical distancing, have forced us to reconsider the value of the restaurant as a social and public space.

Historian Rebecca Spang reminds us that modern-era restaurant culture is rooted in the idea of shared public space. In her book, The Invention of the Restaurant, Spang notes that the term “restaurant” originally referred to the restorative bouillons (not unlike today’s bone broths) that were once served inside the fashionable, spa-like parlours of 18th and 19th century Paris.

“We did a fair amount of seafood that didn’t feel like it would translate well as carryout. Those things worked their way off the menu.”

The bouillon-centric venues, eventually known better as restaurants, helped delineate a new kind of public-private space where people could go to unwind, assert personal preferences through the selection of dishes and drinks, and affirm their social standing by sharing public space with their peers.

Spang, a history professor at Indiana University, believes that one of the pandemic’s long-term effects is how it’s “collapsed” the idea of shared public spaces. “It feels like going out and sitting down at a restaurant is becoming more of a special occasion thing,” she told me. “Through the course of the Trump presidency, and now the pandemic, people have really needed a bubble around themselves, for better or worse.”

Spang notes that the pandemic also overlapped with the explosive growth of ghost kitchens, the delivery-only restaurants with no physical dining space for customers.

Frequently touted by tech companies as “the future of restaurants,” ghost kitchen business models sharply reduce many of the major costs associated with running a brick-and-mortar restaurant, most notably rent and staffing. But as journalist Rachel Sugar notes in her essay, “Ghost Kitchens Will Always Be Dumb,” ghost kitchen menus tend to yield “uncomplicated comfort foods, largely inspired by what tech platforms say people are searching for on apps.”

These menus feel, paradoxically, at once individually customized and computer-generated, a marriage of digital marketing and technology that writer Aaron Timms has described as the “appification” of delivery. Perhaps not since the first wave of drive-thru restaurants have we experienced such large-scale depersonalization of ordering and eating restaurant food.

Ghost kitchen menus also bump up against a nagging philosophical question that has become less avoidable during the pandemic: What exactly is a restaurant? Is a semi-permanent food stand a restaurant? Is a food truck a restaurant? Is a “chef driven” dinner series held at different weekly venues a restaurant? Is a pixelated logo on your phone screen a restaurant?

“I think we’re limiting ourselves by forcing people to go to this one place. Why not bring that place to them?”

Eric Rivera, the Seattle chef and restaurateur behind the chef’s-counter restaurant, Addo, acclaimed for its out-of-the-ordinary 15-course tasting menus, has been rethinking the basic definition of restaurants and menus.

“I recently became familiar with the term ‘Software as Service,’ So I thought, ‘What if I was a ‘restaurant as a service?’” Rivera told me.

He envisions a bespoke online platform where a menu is not a piece of paper, but rather a slate of digital options: Customers would be able to log in for cooking classes, kitchen gear recommendations, or other customized culinary content. The idea of a restaurant as a physical space is limiting, he says—what we really crave are the personal interactions that happen in those spaces: “I think we’re limiting ourselves by forcing people to go to this one place. Why not bring that place to them?”

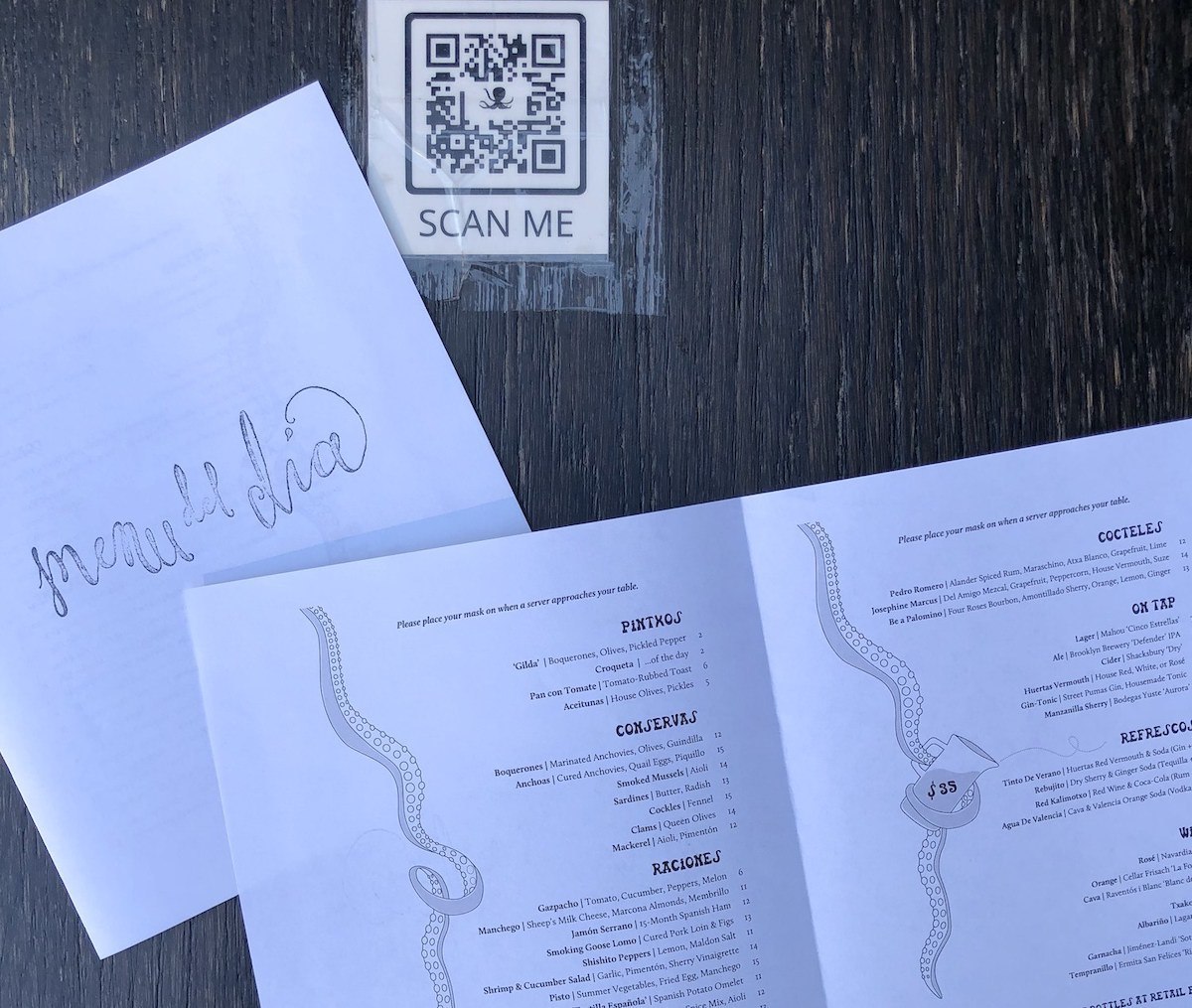

Are restaurant menus fated to live someday only on our computers and phones? The future already seems here—“contactless” ordering became a defining feature of pandemic-era dining, with online menus and Rorschach-like QR codes supplanting traditional printed menus at many restaurants. QR codes have been widely adopted by restaurants and bars during the pandemic. They are transforming the dining experience by diminishing the social interactions that have been a defining feature of eating inside restaurants since time immemorial; the technology makes it possible in many cases to read the menu and pay for food or drink without having to communicate with the restaurant staff. The technology also has privacy experts worried that it makes diners vulnerable to surveillance.

The decline of printed menus may seem small in relation to everything else we have lost in the pandemic. But we lose a lot when we lose printed menus. They are meaningful cultural artifacts, telegraphing with precision how we eat outside the home kitchen. (The fascinating Menu Collection at downtown Los Angeles’ Central Library provides direct, physical evidence of the city’s shifting demographics and trends. The University of Nevada, the New York Public Library, the University of Washington and the Culinary Institute of America are among the cultural institutions and colleges in the U.S. with large, searchable archived menu collections).

What pandemic-era restaurant menus ultimately reveal is fragmentation, said Spang, the historian. The sheer variety of menu forms and types speaks to the way food and dining has become increasingly siloed and compartmentalized and designed to fit into our increasingly sped-up digital lives.

“I really think that what’s happening with food culture in the United States is you cannot possibly speak of a single food culture or a single restaurant culture. It’s fragmented in so many ways,” Spang told me.

This fragmentation is being driven by disparate and often conflicting appetites: We want speed but also quality. We want convenience but also value. We want to be safe, but crave also the freedom to eat and drink alongside strangers inside big, loud dining rooms. The place where these negotiations often happen is on the restaurant menu, which is constantly being reshaped to fit our desires.