Meklit Gebre-Mariam

We’re saying goodbye to beloved culinary traditions. We’re saying hello to an uncertain, potentially exciting future.

I sat in my family’s empty restaurant as Dad stepped out of the kitchen and removed his mask. He checked all the tablets: UberEats, Postmates, DoorDash. There were no orders.

Ethiopian food, at least in the traditional style of eating it on a shared plate, with your hands, was no longer feasible in a Covid-19 world. Two weeks after the shutdown, limited to only takeout and delivery, we had to innovate if we wanted to survive.

We spent days in the kitchen tinkering with new menu items that would travel well. “Does it have to be a bowl?” Dad asked. “Yes,” I replied, “millennials love bowls!” Dad rolled his eyes. I could sense his frustration. He had opened Rosalind’s, L.A.’s first Ethiopian restaurant, in the early 80s; the L.A. Times called him the Godfather of Little Ethiopia, the neighborhood that grew up around Rosalind’s. I had worked at the restaurant for half a summer when I was 15. I was the worst combination, naive yet pushy.

Dad had catered to Western preferences before, downplaying the spice of a dish or two. But to him, removing injera felt like the ultimate sacrifice.

I insisted because I was scared we were going to lose the restaurant. I think Dad was too. Most of the staff at Rosalind’s has worked there since before I was born, so there was a lot at stake. But neither of us could admit our fears. So instead of discussing our feelings, we talked about food.

The worst disagreement was about injera, the foundation of Ethiopian meals, a spongy bread that soaks up the meat and spices on your plate. I wanted to get rid of it because it limited our appeal. Dad had catered to Western preferences before, downplaying the spice of a dish or two. But to him, removing injera felt like the ultimate sacrifice.

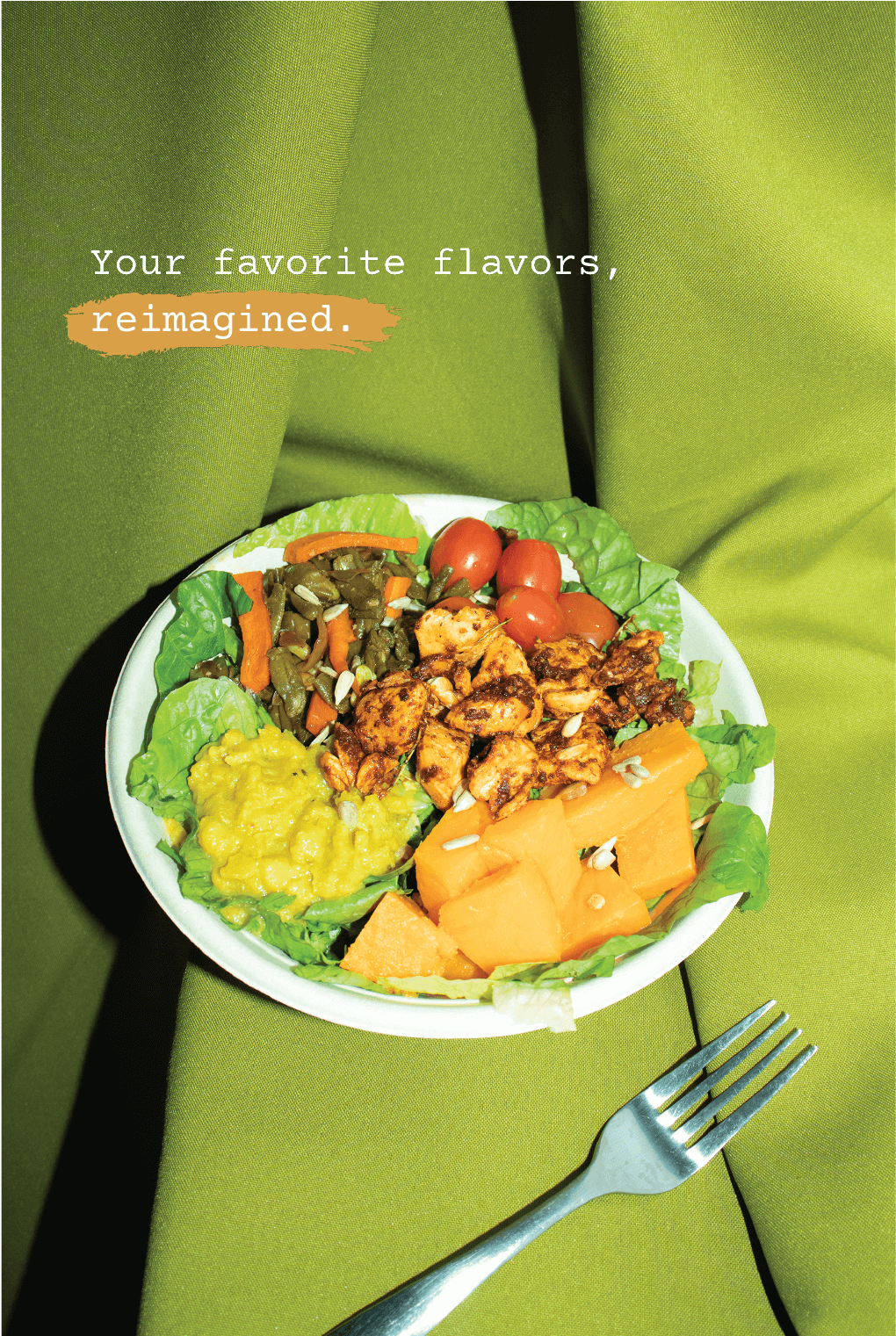

A few days later, I showed Dad images of bowls from Sweetgreen and Tocaya, and for the first time, I saw a hint of excitement. That night, he came home and asked, “What if we added plantains?” It was a traditional Ethiopian ingredient, filling and colorful. Not only had we found something we could agree on but we’d also found the last missing ingredient to our newest menu item, the Sheba bowl: yams, cherry tomatoes, plantains, yellow split peas and yedoro tibs, which is marinated chicken. And plantains, all of it over salad with our house dressing.

Meklit Gebre-Mariam

The new “Sheba Bowl” from Rosalind’s Ethiopian Cuisine in Los Angeles, California.

To me, bowls were a catalyst for something more daring: fusion, perhaps Ethiopian tacos, sambusas with sriracha dipping sauce, something with kimchi. I wanted to introduce the world to Ethiopian flavors before someone from outside our community did. It happens all the time: Small immigrant-run restaurants, like ours, struggle to stay afloat while high-profile chefs open fusion restaurants and earn praise for innovating our cuisine. I wanted us to be able to tell our own story.

We had no orders the day we launched the bowls, though Dad lingered past closing time in case there was a last-minute one. We waited a whole week until that first order came, and when it did I felt like I could finally breathe.

I nervously brought up the idea of fusion. Dad said, “Do you know how hard it was to get Angelenos to try Ethiopian food in 1985?” Then he shrugged. “We were pioneers then. It’s only fitting we explore new frontiers now.”

It’s too early to tell you how this story ends. But when we talk about the future, Rosalind’s is still very much a part of it.