Cristiana Couceiro

Cody Easterday wagered hundreds of millions of dollars on the price of beef. He lost.

This story was originally published at High Country News (hcn.org) on Dec. 1, 2021.

Illustrations by Cristiana Couceiro.

After the fraud at Easterday Ranches was discovered, owner Gale Easterday steered his pickup onto the off-ramp of the highway and drove head-on into a semi-truck that was delivering his farm’s potatoes.

The afternoon of Dec. 10 was cloudy but clear, the roads unencumbered. And Easterday, who was 79, had been making his usual rounds in an industrial part of Pasco, Washington. He was at the helm of four generations of farming and ranching, a multimillion-dollar operation that grew, packed and shipped a massive amount of onions and potatoes, plus raised beef on feedlots outside of town. His family owned nearby facilities — huge operations involving conveyor belts and forklifts that hoisted pallets onto delivery trucks. Several of the company’s contractors were based in the corrugated metal shops nearby. He often ran errands there, or stopped to chat with the dozens of mechanics employed to tinker with the part of the business he loved best: the farm machines.

But on his way out of town, Easterday steered his Dodge Ram onto a highway off-ramp. It was a particularly confusing stretch, and not an uncommon error for the spot. Police records show as much. He ascended the exit ramp, past signs that warned “wrong way,” and rounded the bend onto the interstate, colliding with a vehicle driven by his own delivery man. It happened very fast. The semi driver could not have avoided it. When he tried, too late, to swerve, the truck and its potato haul screamed across the highway, crossed the center median, and came to a jolting rest on the opposite side, blocking all of the lanes. Officers who questioned the driver found him badly shaken. Another truck had broadsided the semi on its course across the asphalt, and he had scarcely avoided driving over the top of it. Two more cars were struck by flying debris, their occupants mostly unscathed.

Gale Easterday was at the helm of four generations of farming and ranching, a multimillion-dollar operation that grew, packed and shipped a massive amount of onions and potatoes, plus raised beef.

Easterday, however, was dead; his Ram decimated. State troopers had the grim task of contacting his family and puzzling over the scene. There were no tire marks where he might have braked, no sign that he had attempted to avoid the crash.

Afterward, along with heartbreak, there was bewilderment and disbelief. Conjecture in the metal shops and on ranches ran the gamut from illness to injury to suicide. But within two weeks of his death, everyone would know what Gale Easterday likely knew that day: Tyson Fresh Meats — one of the nation’s largest meat distributors — was investigating Easterday Ranches and slowly discovering that Gale’s son, Cody, had sold them hundreds of thousands of cattle that never existed.

The deceit that soon unspooled may seem like a one-off fraud. But while it is indeed an anomaly — an expansive hoodwinking far from normal by ranching standards — it exposed a problem widespread in the beef business, which is that the price of a steak has increasingly little to do with the cost of fattening a steer. That circumstance requires ranchers to shoulder tremendous financial risks. And while it has made corporations the beneficiaries of declining rural wealth, it has also wrought awful wreckage for ranching communities and rural families.

Gale’s son tried to outplay this system and lost.

Maybe he was never going to win.

Cristiana Couceiro

Before the matter of the nonexistent cattle, Easterday was a name of distinction. Easterday Farms had been a part of Washington’s Tri-Cities — the agricultural trifecta of Richland, Pasco and Kennewick — since 1958, back when Ervine Easterday, Gale’s father, saw his fortune in the new freshwater from the Grand Coulee Dam and purchased land in the Columbia Basin. Four generations in, the Easterdays were a powerhouse of ranching and farming. The farm, at a sweeping 18,000 acres, was 60 times its original size, dominated by the potatoes and onions. The family had launched Easterday Ranches along the way, a “finishing operation” that raised cattle from weaning to the slaughterhouse after four or five months of fattening.

The ranch was mammoth by Northwest standards. By the end of 2020, it was producing 2% of the cattle supplied to Tyson, which is a lot. A multinational monolith, Tyson produced one out of every five pounds of chicken, beef and pork in the United States and made $43.2 billion in sales every year. As beef industry heavyweights go, Tyson has few equals. Cody, the youngest of Gale’s children with his wife, Karen, eventually held the reins of the family’s partnership with Tyson. In 1989, he joined the business with his wife, Debby, when he was barely 18, and the couple became co-owners with his parents.

In the daily hum of this meat-making venture and on the farm, Cody was described by one worker as the embodiment of its bustle.

“He is on the go all the time, trying to see what he can come up with or buy,” said Johnny Gamino, who worked as a mechanic on Easterday’s many tractors, trailers, trucks and machines for 15 years. “He was almost like anxious — anxious to do something, get something accomplished. He’s always on the run.”

Working with him and his father was easy to enjoy, Gamino said. Both Cody and Gale treated their staff like equals and looked after them like they looked after their own. When they recruited Gamino, for example, the Easterdays doubled his salary and afterward advanced him $6,000 to buy the land on which he made his home. To work with the Easterdays was to be part of a circuit of father-and-son pitstops, check-ins and brainstorms. Cody was frequently at top efficiency, and Gale was often toting Cody’s three boys in his pickup, the next generation in training. The duo were industrious, driven and often on the hunt for opportunities and deals, angling to better the farm and ranch.

“He was almost like anxious — anxious to do something, get something accomplished. He’s always on the run.”

“What I liked about him was that if anybody wanted to talk to him … he would make time for us,” Gamino said.

By all outward appearances in the fall of 2020, the Easterdays looked better than good. They employed hundreds of workers in their packing plants and on the ranch and farm, and contracted crews for seasonal labor. They were donors and boosters for Republican candidates and campaigns, gifted livestock to fairs in three counties and sponsored one of the region’s biggest rodeos, the Pendleton Round-Up. From steer wrestling to barrel races, they were fixtures in arena box seats and in the community, too.

But there was trouble.

Over the fiscal year ending in 2020, Easterday Ranches’ gross revenues had declined by almost half from the previous year, from $111 million to $65 million. And the ranches’ investments had been wiped out entirely. The farm was similarly failing, with gross revenues falling from $82 million to $52 million and interest income on investments diving even as the stock market was booming.

Coronavirus slowdowns at meatpackers surely accounted for some of the loss — cattle were hard to sell in 2020 while plants sputtered, labor was scarce and the supply chain shifted from restaurants to grocery stores. But a longstanding problem was also threatening the businesses: For years, Cody Easterday had been piling up staggering debts gambling on the future price of beef. To cover his losses, he invented whole herds of cattle on paper, then sold them to Tyson while pretending to raise them on the ranch. In November, after a Tyson worker came to take stock of its herd, Easterday confessed the phony invoicing — for the cattle that didn’t exist, and feed for the nonexistent animals. One particularly eye-catching invoice charged $5.3 million for eight lots of cattle that couldn’t be found anywhere other than on paper.

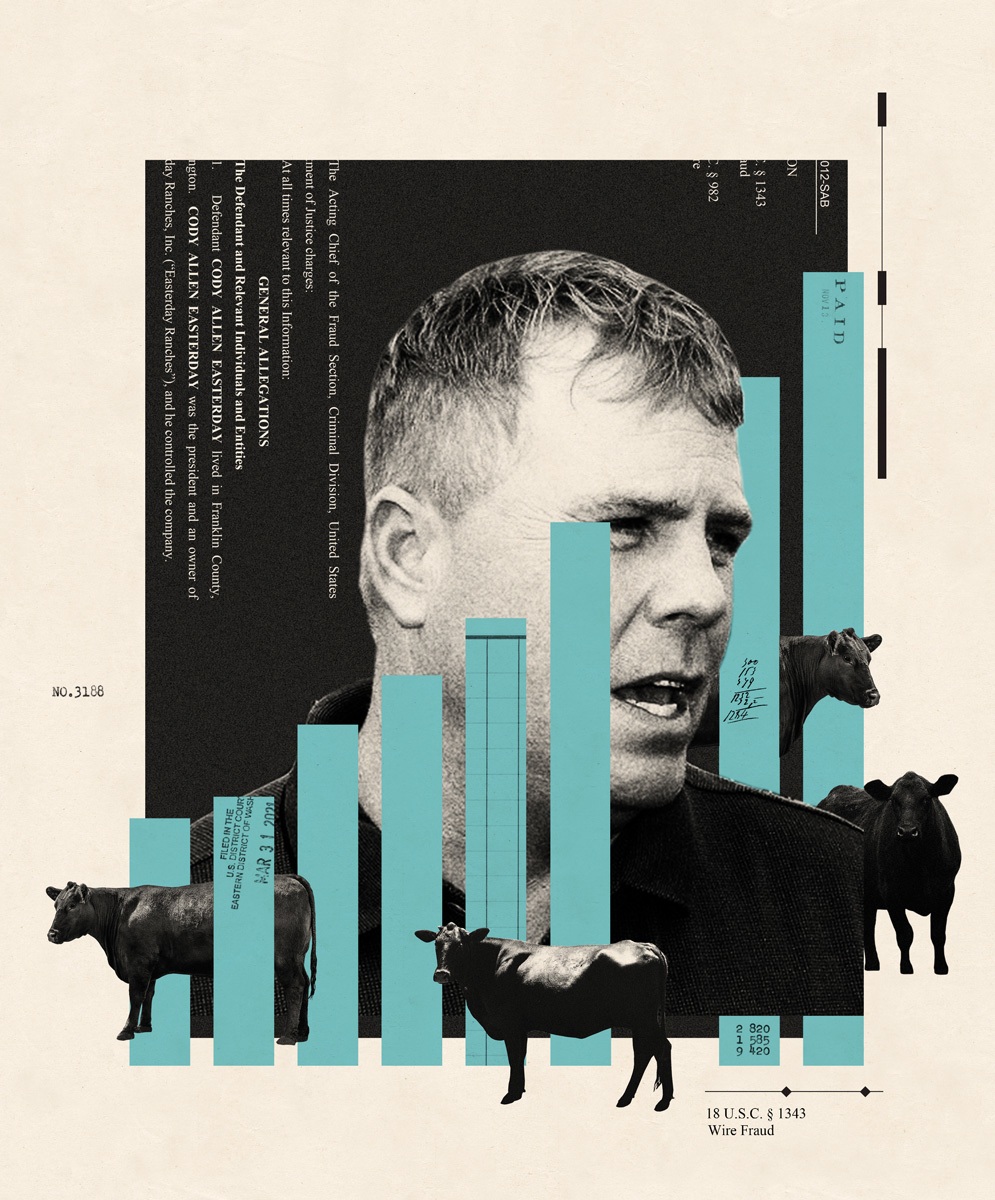

Cody Easterday, through an attorney, declined to be interviewed for this story. Court records explained much of the rest. Maybe the daily ingenuity involved in running the farm and ranch — the deal-hunting and the thirst for productivity — explains a little of why Cody Easterday fell prey to the allure of betting everything his family built. But personal predilection this was not, not entirely.

To understand how the Easterdays unraveled in this system, first you have to know that the system is rigged. And that to be a rancher is to be a gambler — at least in a business sense — because the market for beef is more about enriching corporations than paying ranchers a fair share.

The primary challenge is that 73% of the beef in the U.S. is controlled by four corporations. That’s it. Despite the array of colorfully packaged this-and-that in the grocery store, the corporations either create or acquire the brands that give consumers a fairly anemic range of choice. The meat inside might come from different farms, be raised in different ways, or vary in quality. But at the end of the day, it is bought, packaged and shipped by the same few actors. And because of their market heft, these corporations increasingly influence how the products are made and the prices paid to ranchers to make them. Tyson is among these market heavyweights, along with JBS, Cargill and Marfrig.

Ranchers have long complained about lowball prices from these companies. Nationwide, data from the United States Department of Agriculture shows they have reason to. Profits for ranchers have trended slimmer almost every year since the late 1980s, when those prices were first tracked. By 2020, the same year the Easterday empire began to crumble, a rancher’s share of the value of boxed beef shipped to retailers was 37.3%, down nearly 27% since 2015, when it was 51.5%. This while the consumer price of beef soared higher than ever.

These disappearing earnings were captured by the corporations. They’ve made enormous gains by pulling profits from both sides of the business: pushing pay for ranchers down while also benefiting from the rising price of beef for consumers. Tyson disputes that the company has this much influence over consumer costs, or that consolidation has been a factor. Feeding America requires scale, its officials say. But this capitalistic pursuit — scale — is a primary reason why so many ranchers are going out of business, especially when drought and the high price of hay add other pressures. It’s also why the beef business is consolidating among ranchers like the Easterdays, who instead of raising a few hundred head of cattle on rangeland, raised them by the tens of thousands in feedlots. That industry parlance — feedlots — is shorthand for saying the cattle are raised in pen after pen after pen on dirt squares that look from the sky like enormous bingo cards.

Corporations have made enormous gains by pulling profits from both sides of the business: pushing pay for ranchers down while also benefiting from the rising price of beef for consumers.

Inside this system, Easterday was playing an impossible game. As cattle prices steadily declined, his negotiating power diminished. That’s because while meatpackers like Tyson were buying up all the brands and slaughterhouses, they eliminated his ability to shop around. There were only two corporations operating near enough his ranch to buy his herds. He was already selling to both, including Tyson.

When he entered into his most recent contract with Tyson in 2014, the corporation offered him a deal that’s increasingly common: Tyson agreed to front Easterday the cash to buy weaned calves and to feed them, and to buy the cattle back from Easterday at market rates when they were grown. Tyson would pay premiums for beef quality, and discounts for deficiencies. But while that might seem like a sound arrangement, one with clear expectations and guarantees, it isn’t. That’s because once the cattle were grown, Easterday had to repay Tyson the money the company had loaned him to buy and feed them. Plus, he owed 4% interest on that money. And because no one can know what the market price of beef will be in some months, he never knew whether he would break even. So while this deal brought millions in cash from Tyson to Easterday Ranches in the short term, it could also send that money — and sometimes more — back again. If the price of beef was good, Easterday pocketed the difference. If the price was bad, he was stuck for the loss.

This practice is called formula contracting. It’s a type of forward contract, or a contract that sets prices in the future. And it is not always a ruinous position to be in. But it is risky when contracting with a company like Tyson, because Tyson’s market heft can drive the price of cattle down by eliminating cash competition. Tyson points out the upsides: steady income, reliable markets and easier access to bank loans. But there’s no disputing that formula contracting depresses the price of a steer.

By spring of 2020, formula contracting ballooned to 70% of the market for cattle, more than double what it was 15 years earlier.

Cristiana Couceiro

Cody Easterday must have faced colossal pressure. In addition to employing workers who depended on the farm and ranch, the Easterdays had hundreds of accounts around town. For fuel, for machinery, for fertilizer and things like hay. In those corrugated metal shops where Gale Easterday spent his last day running errands, he was on a first-name basis with the owners of the local enterprises there. After four generations of success, his credit — Cody’s credit, too — it was their name.

Ranchers can manage the financial precarity of raising beef as such a middleman. But to do it well is to treat it more like buying insurance than like a night at the poker table. And ranchers need two things: One is an awful lot of cattle, and the other is a stockbroker.

This is how it works: Ranchers with more than 50,000 pounds of living, breathing, snorting mammal can go to the Chicago Mercantile Exchange — the agrarian equivalent of the New York Stock Exchange — and buy what’s called a futures contract. It’s a paper trade, that’s all. A place to trade bets with investors who are wagering on the future price of beef. With the help of a stockbroker, ranchers can carefully wager against their cattle to make a little extra profit, just in case the market price doesn’t go their way.

Say, for example, that the break-even price on a herd is $1.30 per pound in June. That rancher might buy a futures contract for $1.34, looking to make a profit of 4 cents. That way if the market price turns out to be only $1.20 by June, the rancher might have lost 10 cents per pound on the cost of feeding his cattle, but still netted 4 cents a pound by trading paper. This is how a guy in Greenwich, Connecticut, can come to be placing bets on tens of thousands of pounds of cattle without ever setting foot in a feedlot. And that’s a good thing, because he’s the only one left driving the price of beef up for the rancher.

Some people play this system quite well. Ron Rowan is the director of risk management for Beef Northwest Feeders, another cattle finishing operation in Oregon, and trades cattle futures for a living. Rowan’s knowledge of the beef industry helps him manage the risk at his cattle-fattening enterprise while the guy in Greenwich takes on a share of risk, too. Rowan says the incentives in the formula contracts — the premiums paid for higher quality — combine with this trading to drive better beef cuts and grades. “We’re producing — in my opinion, and look at the statistics, too — the highest-quality beef that we’ve ever produced.” More choice prime. Happier customers. Increased demand. Tyson officials point to these benefits as perks of the current system.

But little ranches can’t play this game. That rangeland? That Western grit and independence? The smallest of players — specifically the ones that rely on grass and forage to feed cattle — are often too small to trade on the exchange. They don’t have enough pounds of mammal.

“It’s not looking rosy,” said Toni Meacham, a rancher in her early 40s who has a second income as an attorney. “You’ve always got Tyson and all those big plants saying, ‘You guys have got to get your costs down.’ And we’re sitting here going, ‘We can’t pencil that, that doesn’t work.’” One of her colleagues bought a grocery store to capture more money on his beef. Another started selling directly to consumers.

“It’s not looking rosy.”

Some ranchers forgo the market altogether now. Federal data shows that the largest percentage of ranchers raise 10 or fewer cattle for themselves, maybe a few friends. In recent testimony to Congress about Western drought, which was so severe in 2021 that irrigation water was scarce, several ranchers described selling off herds at significant losses, unable to buy hay while grass wouldn’t grow and profits were too slim to afford it. Whether those ranchers can borrow their way back into business in another year is unknown. But last spring, cattle moved in droves to large feedlots in places like Nebraska, Kansas and Texas where grass was abundant. That means cattle moved away from the open ranges that are beef’s Americana, and off the free-roaming lands that consumers value.

For the ranchers that remain in business, raising beef is an enterprise of scale — scale and futures trading. But for them, there is another potential snag: While futures trades on the price of beef can earn big, they are extremely risky when they angle into gambling.

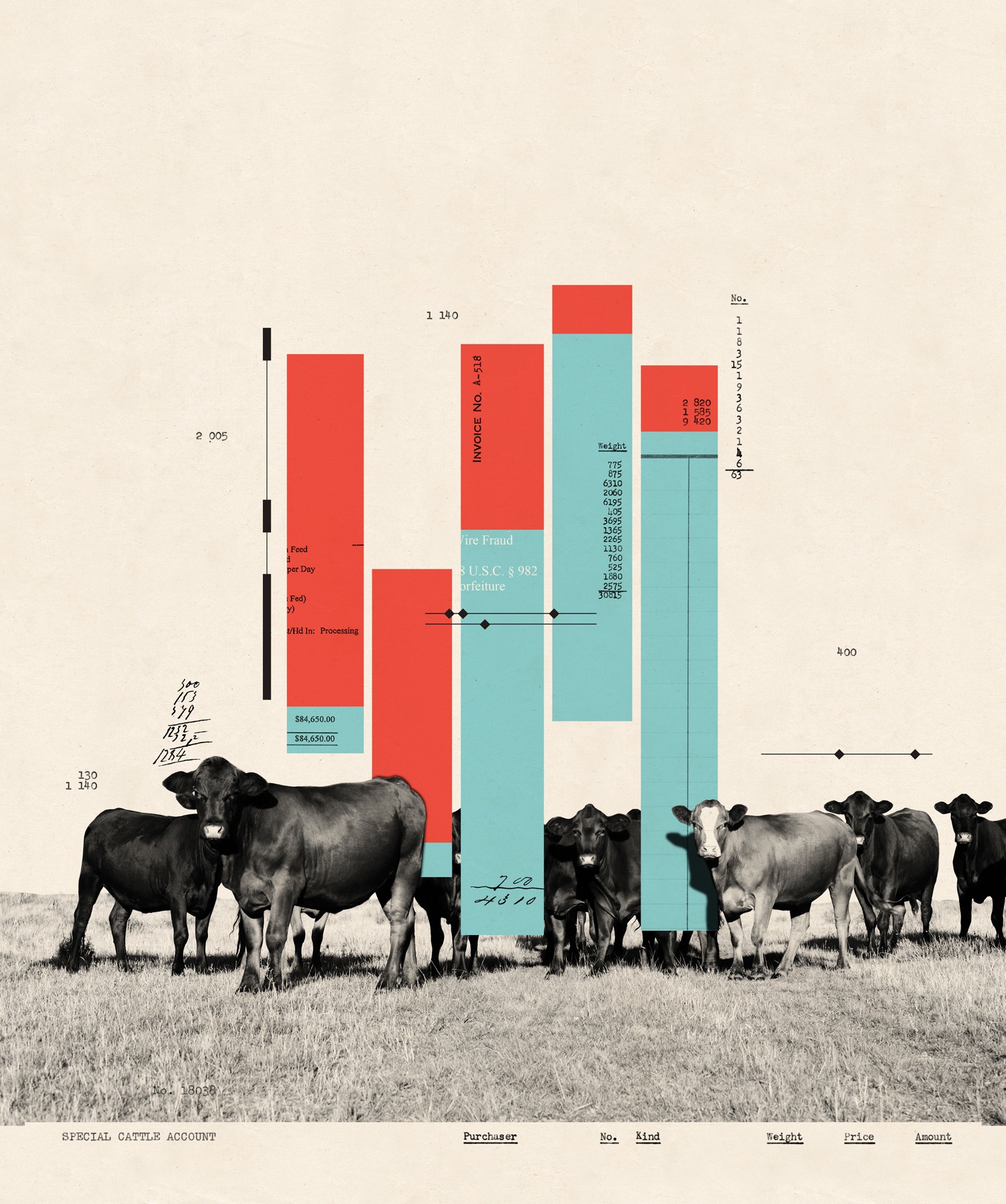

This is the territory that Cody Easterday found himself in: on a first-name basis with at least one stockbroker. Easterday’s first recorded big loss was in 2011, when court records show he lost almost $14 million. He lost another $17 million in 2012. The following year, another $10 million, then another $20 million. Then he won: In 2015, a haul of nearly $7 million turned his luck. But the victory was brief. In 2016, he lost another $6 million. That year, with losses piled high and cash undoubtedly short, Easterday told employees to submit fake invoices to Tyson, a criminal investigation found, billing for cattle he never bought and feed for those imaginary animals. Then he used the cash to pay down his debts and bet some more.

It worked. Sort of. Tyson paid the tab, and Easterday used Tyson’s money to pay down his trading debts. But Easterday quickly lost another $18 million. So he invoiced Tyson for more cattle and more feed he didn’t have. Then he bet again, losing $58 million in 2018. For the next two years, he was in a nasty cycle, billing Tyson for imaginary cattle, then paying down the losses and trading again. Some of the fake invoices included pen numbers, the animals’ gender, even a financial analysis of their prospects in the market. Each sought millions of dollars for thousands of head of cattle. Hundreds of thousands of them were never real.

By the time Tyson began to suspect the fraud, in November 2020, Easterday had lost more than $200 million in the futures market. When confronted by a Tyson worker, and next a trio of corporate honchos, he told them all he had “screwed up” and “pissed it away on the Merc.” He disputed that he had been stealing, called the phony invoices “forward billing” instead.

Cristiana Couceiro

Lots of cattlemen will tell you that Cody Easterday is an outlier. That he fudged receipts, cooked books, made up livestock that were never there. They are quick to note that this is fraud, that it was illegal, that it is very far afield of the normal business dealings of a ranch. They also say that Easterday may have had a gambling problem. All of that might be true.

But what’s certainly true is that the price of a steak is increasingly untethered from the cost of raising cattle. And that the scenario drives ranchers to operate on margins so perilously slim that speculative trading is necessary and spectacular failure possible. Tyson officials say their margins are also slim, slimmer than ranchers’ margins once you factor in all the costs. Only a portion of the company’s $43.2 billion in sales is profit. But for Easterday, spectacular failure is what happened next.

Tyson’s inquiry quickly revealed that at least 200,000 head of cattle purported to be in the care of Easterday Ranches were, in fact, made up. It added up to $233 million in losses for Tyson. The corporation soon disclosed as much to shareholders, along with its own overstated financials. Then, in January, Tyson filed suit against Easterday Ranches to reclaim the money. By the first week of February, while the Easterdays were likely still mourning the death of Gale Easterday, both the farm and the ranch had filed for bankruptcy, their fates left to a federal court.

In a capitalist system, failure like this is felt hardest by the people with the least protection. The people in the box seats at the county fair — the kind of seat that Cody Easterday still claimed — would survive. It’s the workers that earn the least that are at risk to be hardest hit: the seasonal, often undocumented, laborers employed by farms, who are paid piecemeal through third parties for tasks far from the looping highways and bridges of the Tri-Cities, out in the land of irrigation pivots and row crops.

Take Jesus Caldero, for example. He’s an occasional laborer who also works at a farmworker housing complex run by a Seattle-based health clinic. In a brightly colored dormitory there one day, he described through a translator how, in early spring, workers begin at 3 in the morning, ground lit by headlamps, to race the rising sun while picking asparagus. “The way you’re positioned, after 10 a.m., it’s very hot,” he said. He stood to demonstrate, hinging himself at the hips, bending forward to grab a plastic water bottle on the floor by its base. “It’s very uncomfortable.” The trick, Caldero said, is to get up slowly for the first two weeks. Never fast. After that the body, strangely, adjusts. Workers travel between six and 10 miles in this position every day, paid by how much they pick. Usual earnings are around $300 a day.

Easterday Farms contracted hundreds of workers annually. When Easterday filed for bankruptcy, it owed $47,000 and $454,000, respectively, to two farm labor contractors who supplied such workers. Called FLCs for short, the companies — Rangeview Ag Labor and Labor Plus Solutions — hire the migrant and local laborers who work the fields, most of whom come from the Latinx community. FLCs organize, transport and manage pay for these crews, which in turn supply farms like Easterday with frequent on-demand help doing these most difficult and timely chores.

Spokespeople for both companies declined to be interviewed, but Erik Nicholson, the former vice president of United Farm Workers, who is now a consultant, said the outstanding sums would be painful blows for both. “Most of the FLCs are woefully undercapitalized,” he said. “They operate paycheck to paycheck. For an FLC, that is a huge hit.”

These kinds of losses also hit the corrugated metal shops. At the Olberding Seed warehouse, set on a thin tract of land between the airport and the railroad, the tab was $160,000. It was $503,000 at Industrial Ventilation. The Easterdays supported mechanics and parts stores and irrigation specialists all over town, often keeping large accounts open. All told, 230 small businesses were owed money, from small sums to millions. All were at the back of the line by bankruptcy standards, outranked by creditors like Washington Trust Bank, Rabo AgriFinance and John Deere Financial, which piled on their own litigation, anxious to be paid for loans. Those heavyweights were secured by contracts or collateral, something other than friendship.

Repaying all of them seemed an outsized task. In addition to the $233 million owed to Tyson, there was $223 million in debts across the ranch and farm for usual things. Mortgages, bank loans, purchase agreements for vehicles. Only $51 million remained in assets. In a bankruptcy hearing, an attorney for Easterday Ranches acknowledged the shortfall, telling a judge, “The pie is not big enough.” He said he was shopping a settlement agreement to avoid the years of litigation that could erupt in a fight for what was left.

“The pie is not big enough.”

Still, few small business owners wanted to talk about the money Easterday owed them. “You don’t get paid, you move on,” said Brad Curtis, whose farm was owed $112,000 for feed. He reasoned that if money was left over, much of it would probably be eaten up by attorneys.

Others also demurred, a verbal shrug, as if the shock of losing the money was less than the shock of losing an institution like Easterday Farms. Business with the Easterdays had always been good, they said. Worth the trouble for this stretch of bad. And maybe business with the Easterdays would be good again with the cousins or siblings or sons who remained. They suffered the loss and claimed not to be bitter with Cody. They talked of his community leadership. Of sticking together. Of proud traditions like raising your own livestock and eating steak.

After Tyson reported Cody Easterday’s fraud, federal investigators swooped in for their own examination, referring to the situation in shorthand as the “Ghost-Cattle Scam,” while ranchers called it “Cattlegate.” Tyson continued with its own investigation, dispatching the corporate honchos to debrief Easterday in a pair of meetings in which he detailed how he’d scammed them, sharing meticulous notes on the cattle, even the imaginary ones. Tyson employees, shocked by his stoicism and cool demeanor, checked his math by flying drones over the ranch to count the cattle.

On March 24, the Department of Justice charged Cody Easterday with a single count of wire fraud for sending the fake invoices to Tyson over email. It was a crime punishable by up to 20 years in prison and fines. In charging papers, Easterday was also accused, not only of bilking Tyson out of $233,008,042, but of replicating the scam with an unnamed company and defrauding that one of another $11,023,084.

Easterday’s capitulation was swift. Within a week, he pleaded guilty to the charges, agreed to pay $244,031,132 in restitution and began awaiting sentencing for possible jail time. By the end of May, the farm was set to be auctioned. Easterday was in Idaho on vacation, visiting his daughter for the birth of a grandchild with permission from a federal judge.

In the interim, because the coronavirus had bottlenecked beef processing and prices for consumers had spiked, pay for ranchers had fallen to an historic low of 31.1% before rebounding to 35.8% by June. The USDA had investigated, as had the American Farm Bureau Federation. They didn’t find any price fixing between Tyson and the other meat companies. Nothing illegal. But before long, white papers began to point to formula contracts as a key driver of the falling rates of pay. The USDA suggested one possible fix could be to create more trading tools for smaller ranchers, allowing those with fewer cattle to get in on the trading game. This way those ranchers who were shipping cattle south could also hedge their herds.

In June, while the Biden administration was talking of breaking up the corporate meat oligopoly, bidders for Easterday Farms and Ranches were few. The bankruptcy court opted not to split the four generations of sprawling business. While small pieces might have stayed in the hands of other smaller operators, the court reasoned it could capture more money for debts more quickly in one whopping sale. The onions and potatoes. Row crops, plus cherries and grapes. A feedlot (another had been sold). Onion and potato storages, other buildings, too. Plus piles and piles of land and land leases totaling 22,500 acres, 12,100 of them irrigated. All were advertised to whatever deep pocket could come along and help Cody Easterday and his lawyers bail water.

Only two buyers made offers. Both were real estate investment firms that turned profits on ag land. One was Cottonwood Ag Management, a subsidiary of Cascade Investment, owned by Bill Gates. The other was Farmland Reserve, the investment arm of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the parent company of AgriNorthwest, which operates farms in and around the Tri-Cities and elsewhere. It won the farm with a bid of $209 million.

Proceeds from the farm and ranch are not intended to benefit whoever lives here now; it’s to pad the profits of the LDS Church.

After that, anyone curious to see the old Easterday farm would need an airplane and a bit of time. AgriNorthwest had surrounded and dwarfed Easterday Farms for years, owning hundreds of thousands of acres north of the Columbia River and east of Highway 395, south to Hermiston and Boardman in Oregon. Though the company hired a quarter of Easterday Farms’ staff and rebooted many of their family’s contracts in the community, the transition to investor ownership could mean fewer donations to the county fairs, local Republican candidates and other causes the Easterdays championed. Proceeds from the farm and ranch are not intended to benefit whoever lives here now; it’s to pad the profits of the LDS Church.

Such behemoths are the heirs apparent to more than just the Easterdays’ lost fortunes. In an era of downsizing farms and ranches, they are the chief beneficiaries of farm economies that increasingly revolve around commodities of scale and investment. Maybe this was good news for Cody Easterday, who could finally gain something from the consolidation and higher prices.

When the sale was over, bales of straw were tarped by the hundred in a long, tall row outside a former Easterday feedlot. There were no cattle inside the hundreds of pens, just a flat expanse of soil and an eerie quiet in this place where millions of cattle once lived, and hundreds of thousands of invented ones never did. Down the hill, a row of farm machines lined a field that sloped skyward to meet the blue day. Tractors, trucks, trailers, a bulldozer, a couple of golf carts, next about to be auctioned.

The family had scrambled for what last money it could. Over the farm’s last year, the Easterdays secured $2.6 million in pandemic-related Paycheck Protection Program relief, the Tri-City Herald, a local paper, reported. Court records show credit card bills in Debby Easterday’s name were paid — $153,405.19. And another $30,249.72 in cash was spent for things like trips to Costco and plants. Someone took a $3,200 trip to the periodontist. And $23,000 in tuition was sent to a college in Virginia. The money flowed with an ease unlikely to resume.

The next generation of Easterdays who might have otherwise inherited what he lost — the grandsons who spent their youth riding shotgun in Gale’s pickup — now farm farther from the Tri-Cities.

Cody Easterday awaits sentencing while the government comes for the rest of what is his. He’s still a fixture in the box seats at the rodeo. Got a second hall pass from a federal judge to visit the new grandbaby in Idaho.

The next generation of Easterdays who might have otherwise inherited what he lost — the grandsons who spent their youth riding shotgun in Gale’s pickup — now farm farther from the Tri-Cities. The land is southwest of Boardman in Oregon, where much of what’s for rent is owned by another real estate investment firm. It’s also near the 28,000-cow dairy that Cody’s son proposes to operate instead of his father. But it’s unclear whether the dairy — a hoped-for venture that’s all that’s left of the Easterday empire — will ever start up. It has a history of environmental violations under a former owner and may never get the permits it needs. And it’s still unknown whether the dairy can avoid being embroiled in the tangle of debts that have ensnared the farm and ranch.

For now, it’s just a handful of buildings, plus aisle after aisle of empty cow corrals — another place where the animals that might have lived here are only ghosts.