From toast to theme restaurants, the avocado has soared in popularity in the United States. Consumption is up from 436.6 million pounds annually to 2.4 billion pounds between 1985 and 2018.

The discovery could help growers breed more disease-resistant avocados, and eventually lead to varieties that are drought-resistant or less temperature sensitive, and can be grown in northern and drier climates. More growing options could help supply match demand and protect shoppers from a price hike like this year’s. In early July, avocado prices were 129 percent higher than they were at the same time in 2018.

Despite the study’s findings on disease resistance, researcher Victor Albert, one of the study’s authors, says that avocado tree roots are susceptible to fungal rots. One possible solution, he says, is to use genome-assisted breeding—that is, identify a gene that performs a protective function, look for that gene in various avocado varieties, and then breed new strains that contain the desired genes. (CRISPR guacamole, anyone?)

Albert says that the avocado species was a “natural study topic” for him. In addition to being a professor of biological sciences at the University of Buffalo, he is an evolutionary biologist with interests in the genomic bases that differentiate plant species. He believes that climate change and accompanying disease changes are the biggest factors that impact avocado agriculture, and felt this research would be helpful for the future of avocado breeding.

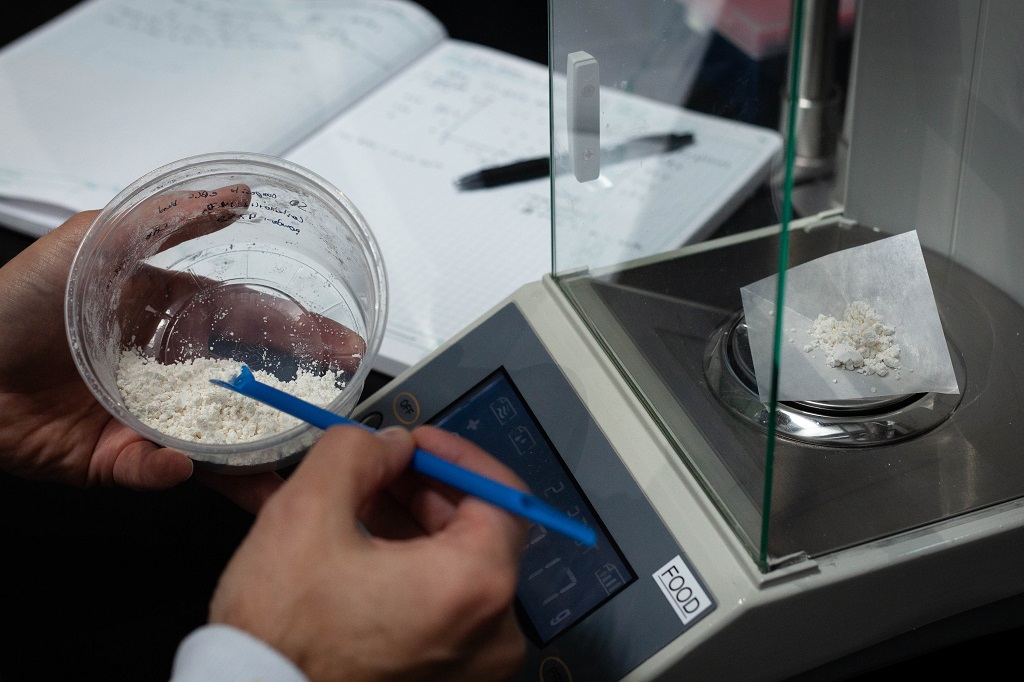

In order to conduct the study, researchers had to isolate the DNA from avocado leaves and—in computing terms—sequence it in a “massively parallel fashion on state-of-the-art genomics equipment,” Albert says. In lay terms, that means they used several computers simultaneously to gather data on the avocado that they then analyzed in comparison to other plants to “see what avocado’s secrets were,” as he describes it.

But Michael Clegg, an academic researcher and retired professor of biological sciences from the University of California, Irvine, estimates that it will be 20 to 30 years before we see any economic value from the findings. That’s due in part to the high costs of field tests. And even that might not be enough time. “We tend to underestimate the time it takes for an innovation to develop from basic knowledge to final product, and this is especially true in plant improvement,” he says.

In the meantime, the avocado’s popularity has a downside. In 2016, Michoacán, the Mexican state that produces most of the country’s avocados, dealt with illegal deforestation to keep up with demand and a hike in activity from criminal organizations like Los Caballeros Templarios (The Knights Templar). Local residents voiced concerns that the growers’ use of chemicals caused breathing and stomach problems for their children.

And lower prices aren’t good news for everyone. “While growing more avocados means lower prices for buyers, it also means there’s a loss of value for growers,” says Albert.