iStock

Last week, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced its intent to regulate lab-grown meat—a declaration that provides some clues about how the federal government will treat a new technology that upends some notions about food and agriculture.

In some ways, it’s unremarkable that lab-grown meat would fall under FDA’s purview. It’s the federal agency that’s already in charge of ensuring the safety of most foods, from Hot Pockets to baby carrots and coconut water. What is surprising, though, is FDA’s signaling that it wants domain over a meat product. That’s always been the responsibility of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

In theory, USDA regulates meat, poultry, and most “egg products,” like pourable egg whites, and FDA regulates everything else. In practice, the relationship between the two agencies is byzantine. A jurisdictional disagreement over mislabeled egg rolls led to a protracted regulatory standoff last year; FDA is responsible for closed-faced sandwiches, while USDA regulates their open-faced counterparts. This announcement suggests more confusion. While USDA will continue to regulate meat from animals, FDA wants to oversee cell-cultured meat grown in labs.

In his letter, Gottlieb indicated FDA would regulate lab-grown meat because the technology has the potential to resemble other medical advancements, like growing human organs from scratch. That’s not a stretch. As lab-grown meat gets more complex, and begins to resemble actual bluefin tuna steaks, instead of a tube of fish paste, it will require the kind of structuring, or “scaffolding,” that scientists are already using to emulate human lungs and livers.

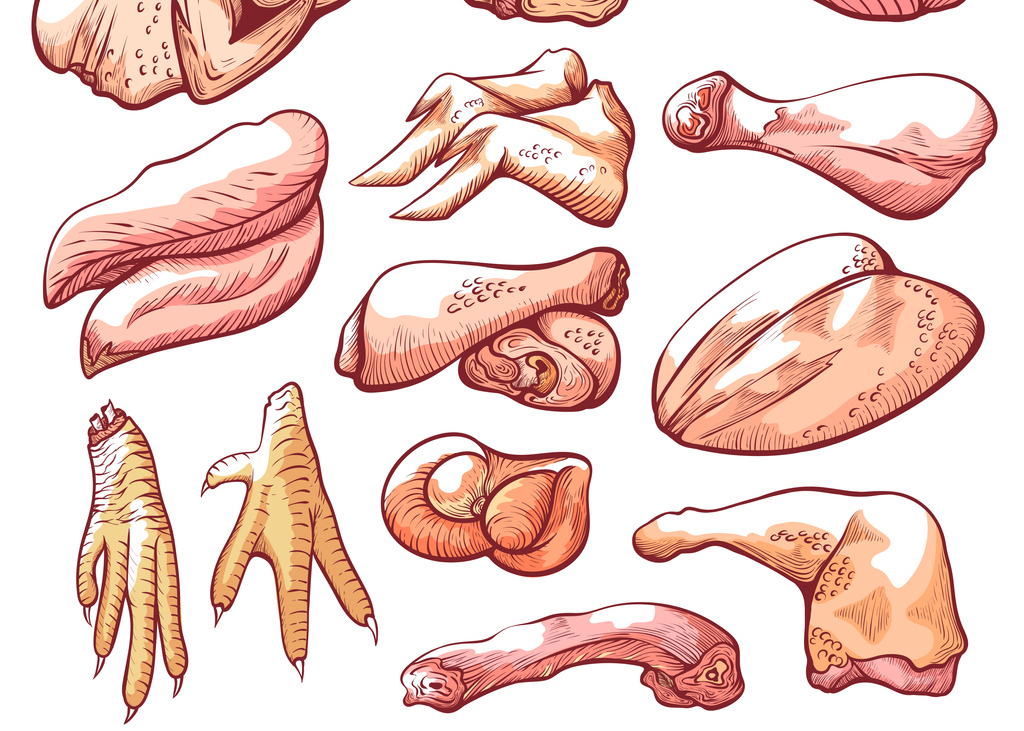

Lab-grown steaks, and other foods that resemble actual animal muscle, are likely years away from hitting supermarket shelves. Though leading companies like Just Foods and Memphis Meats are working on growing duck and chicken meat from animal cells, culturing them with protein serum, and growing them to scale in bioreactors, the resulting products are still paste-like in consistency. (Think pâté or foie gras.) For now, cellular agriculture is a fermentation process, which is how beer, cheese, and medical products like insulin (all of which fall under the purview of FDA) are made.

That’s likely to infuriate traditional meat companies, who may feel that USDA has their interests at heart, and not those of lab-grown competitors. Politico reports that the National Cattleman’s Beef Association, an industry group that has pushed legislation that would prevent Silicon Valley companies from calling their products meat, was “dismayed” the agriculture department was not included in the announcement.

But proponents of cellular ag argue that USDA, which is historically tasked with slaughterhouse safety and the inspection of animal carcasses, is ill-equipped to evaluate next-generation products that don’t involve animals.

“The nascent clean meat industry needs as much regulatory certainty as it can get, and it needs regulatory partners who are familiar with the science these start-ups are doing,” Paul Shapiro, the former Humane Society vice president, and author of Clean Meat, told The New Food Economy in an email.

The FDA is accepting public comment on animal cell-cultured foods through September.