This week, our senior editor, Joe Fassler, joined Katy Kieffer, host of “What Doesn’t Kill You: Food Industry Insights,” and Sally Lee of the Rural Advancement Foundation International to talk about his story “Playing chicken.” The article covers a class action lawsuit that claims poultry processors have conspired to keep farmers trapped and dependent.

Listen to the story using the Sticher player below, on Heritage’s site here, or read the transcript below (it has been edited for clarity and length). The conversation picks up at around the 06:30 mark.

Katy Keiffer: Joe, the reason you are here is that you wrote a piece in February called “Playing Chicken” that describes not only how contract growing operates through the perspective of a grower but, more importantly, it describes a recent class action suit, which “alleges that five of the country’s poultry companies, Tyson, Perdue, Pilgrim’s Pride, Sanderson Farms, and Koch Foods have colluded for years to keep farmers in debt and underpaid.” Describe that suit and what success would mean for contract growers if they prevail in this suit.

Joe Fassler: I think the first thing that’s important to point out is there are actually two major class action suits against the poultry industry right now. The second one is the one that you mentioned that’s on behalf of farmers, but the first one is actually on behalf of chicken buyers.

Katy Keiffer: Basically, on behalf of distributors and grocers. Right?

Joe Fassler: Exactly, and what they said was that the major integrators–which is the word for the big chicken companies Tyson, Sanderson Farms, Perdue, and many others–used a database called Agri Stats to kind of collude and exchange business information in a way that created a noncompetitive environment. Basically, it was like a clearing house for information where the companies could kind of monitor one another’s various numbers, of all kinds of different data and stats, without actually having to necessarily get into a room and talk about them.

Joe Fassler: Now, both suits alleged that some of that does happen but the sort of crux of it is that allegedly these central clearing houses were a way for them to swap their sort of business secrets.

In terms of the farmers’ suit, what is alleged is that they were about to say, “Okay, we have certain farmers in this neck of the woods.” Because the clearing house has geographic information, too, right? It allowed them to specialize in different regions of the country and not have to compete with one another, which–if true–would make a much more difficult situation for farmers, because they don’t have multiple integrators to work with.

Katy Keiffer: Right.

Joe Fassler: So that’s kind of the crux of it, saying that this collusion has artificially suppressed the kind of incomes that farmers were making because the businesses had this advantage by being in conversation.

Katy Keiffer: Absolutely, absolutely. So Sally, why don’t you tell us a little bit about why growers get into the contracting business? Because it really seems like if you do any reading at all about being a poultry farmer, it seems like a losing proposition from the get-go. How is it that they are able to entice farmers? And Joe just mentioned the fact that they were making more money in the past, and then with the price fixing that’s allegedly gone on in the last (I think) ten years. They are making less money. So walk us through: Why would somebody get into the contracting business? And how could they see that as a winning solution for them in terms of generating income?

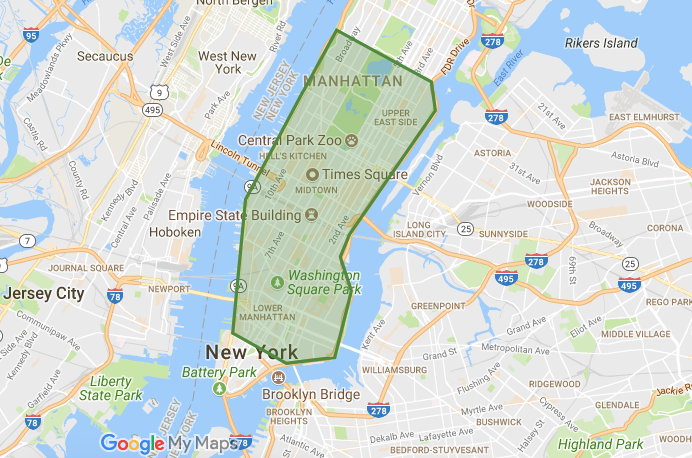

Sally Lee: Sure, well the stories that farmers told in the past are certainly part of it, because many new farmers getting into it now have heard from older growers or maybe even family members that this was a good business, and they don’t realize the changes that have happened. Another thing that’s really useful to understand is that this industry is very geographically concentrated.

Katy Keiffer: Right.

Sally Lee: And it’s very prevalent in areas where there isn’t necessarily another major industry where other kinds of farming ventures are as lucrative. That’s really what we call the broiler belt in the southeast.

So if you’re a farmer in these regions, you don’t have a whole lot of options, and when a company comes in and starts holding town hall meetings to recruit for new contracts and new houses, that’s a really big deal. A lot of farmers will see this as an opportunity to maybe bring their kids back home to work on the farm, or as a way to establish some cashflow that they desperately need because some of their other farming ventures are not going so well. The storyline that I think is really important, that the companies will promote at these town hall meetings and use as a way to recruit farmers, is that this contract is going to be a steady job, unlike other aspects of agriculture. It’s going to be guaranteed income. It’s going to be guaranteed cashflow. And they promise farmers that this is an honest industry that operates on honest competition so the harder you work the more you’ll get paid.

Farmers are very hardworking people so this sales pitch really appeals to that entrepreneurial American farming spirit. But what they don’t tell farmers is that that contract is actually loaded with loopholes for the company, so once they get the deal worked out, and farmers have signed on to hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars worth of debt, the company can come back and change the deal, and leave the farmer stranded under that debt.

Katy Keiffer: Mm hm. (affirmative) So that brings me to Joe. You mentioned in your piece that the integrator, and that would be again the big chicken companies (the Tyson, the Perdue etc.), keep tabs on the amount of debt that their growers acquire in the service of either building or upgrading housing. How did they get access to that information. Shouldn’t that be private?

Joe Fassler: Tyson denies this. I’ve asked them directly about it, and I haven’t spoken with, say, Perdue and others, but my guess is that they would say no, they don’t do that. Anecdotally I’ve spoken to farmers who say that that is the case. I bet Sally can chime in on this but I think that there’s a couple of ways that it could theoretically happen even if it wasn’t necessarily a strategy that was by design.

One of those ways is that the chicken houses are sort of upgraded in waves. The farmers whom I talked to in the piece actually gave a pretty good nutshell history of how chicken-growing houses have changed over the years, because as technology comes up, it sort of rolls in waves through the houses. I think the industry has a good sense of when the last required upgrades that they stipulated came into place. Sometimes there are 200- or 300-thousand-dollar upgrades that are necessary, and those are amortized over often a contract of 20 years or more.

So there’s usually a sense of where the farmers stand in that regard. The farmer I spoke to for the piece said that she would see the local Tyson representatives also meeting with the farm credit people in the local restaurant in town. But I can’t speak to that.

Katy Keiffer: Right, right. The farm credit bureau is a lender, right? Or something like that, there’s a bank that’s affiliated with the farmer … I don’t quite understand how that financing works but I do know that there are institutions that deal specifically with agricultural concerns in terms of load advancing money. It makes me wonder (and Sally by all means chime in on this)if those institutions are colluding with the big companies on a certain level. Like a company will come in and say, “Hey, farm credit bureau person A, we want to generate some upgrades because for whatever reason we need these upgrades, and we want to talk to you about pricing a loan.” I’m wondering how much influence they have over the actual lending institution and the types of loans that it will write for growers.

Joe Fassler: Right. One thing that’s definitely true (and I’d be curious to hear Sally’s perspective on this because Sally you’d know a lot more than me): Generally poultry farmers I think tend to have some of the most debt in agriculture, period. For whatever reason, they are able to get a lot deeper and deeper into debt than others are.

Katy Keiffer: Yes. Mind blowing.

Joe Fassler: So there are norms there—the ability of poultry farmers to get loans when they’re deeply underwater seems to be different than in other forms of agriculture.

Katy Keiffer: Yeah.

Joe Fassler: But I’m not sure really how that came to be, and Sally I wonder if you have any thoughts.

Sally Lee: Yeah, a couple actually. There’s some direct reasons why that is, which are related to taxpayer money. One thing that’s useful to understand: When a company is coming into new area, they will work with private banks, with Farm Credit, or with others to discuss the fact that they’re coming in. They’re going to be expanding by 500 houses, and they’ll give cashflow estimates, and kind of work out in discussion with banks what they’re looking at in terms of farmers’ debt load. Banks are very much a part of the process of expanding this operation so they’re involved. The farmers’ paycheck will often go from the company to the bank directly rather than the farmer receiving the paycheck and then paying the bank back their debt. It’s called an assignment process.

Katy Keiffer: Wow.

Sally Lee: While it might not be collusion, there’s definitely cooperation in the system. The other thing that’s really important about we taxpayers is that we actually finance these loans in large part or we back them. The Farm Service Agency [FSA] and the SBA, Small Business Administration.

Both are able to guarantee up to 90 or 95% of the loans that meet certain criteria within our regulations. And a big portion of those backings go towards chicken operation loans–especially for the FSA, and increasingly now for the SBA. What that means is that farmers are going to come in to a bank, and they’re going to say, “I would like to get a 1.5 million dollar loan to build these chicken houses.” And the bank will say, “Well, we think that’s too risky because we’ve seen some foreclosures. We don’t want to take that on.” But the farmer can then apply to FSA and get a guarantee, and if they come back to the bank with that guarantee, then the bank has very little risk in this lending at this point.

Because the taxpayer would be taking a major kick if the farm were to go under, and they couldn’t sell it off for the amount that was owed. The bank is now willing to make larger loans and more frequent loans than they would necessarily without that guarantee.

Guarantee loans are a really important part of the credit infrastructure for farmers. They help socially disadvantaged farmers get access to credit that they wouldn’t otherwise have, and they help farmers in emergencies, but, in the case of poultry loans, they’re being abused a little bit by the industry because the industry knows they’re a way for farmers to take on excessive amount of debts.

Katy Keiffer: Right, that they really would have a very difficult time paying back. And that leads me to the next question for you, Sally, which is that you have a great page on your RAFI website on the facts and figures of the poultry industry, and among them is the average income for a grower under contract to one of the top five integrators.

Can you talk a little about those figures? Because they were a real eye-opener for me: So far below the poverty level for a family of four on the regular score that it’s just kind of mind blowing, and it speaks to this ability to borrow more money than you should be able to. It reminded me of the housing bubble where people who had an income of maybe 30,000 dollars were buying houses that were so far beyond their means.

Sally Lee: There are a couple of things. It’s interesting when you talk about chicken contract farmer income, there’s a lack of very concrete information in some areas, which is a result of the companies’ use of Agri Stat that we mentioned earlier in those lawsuits.

Katy Keiffer: Yup.

Sally Lee: They keep a lot of that data private but what we do know from looking at USDA data, is that farmers are completely dependent on contract production for their livelihood, and that up to 70% of them are living under the poverty line, which means that this industry does not pay enough for a family to subsist on and pay back their debt. That’s very clear.

Many chicken farmers also have other farming operations. So that while the top 20th percentile of family households with chicken farms but including all of their sources of income (it could be off-farm jobs, cattle, everything else) have an income on average of a hundred and forty-three thousand, which is pretty high, the bottom 20th percentile has an income of 18,000.

Katy Keiffer: Right.

Sally Lee: Which is incredibly low, and so what we see when we look at these numbers, numbers that even USDA researchers note as a red flag, is that this farmer paychecks are incredibly variable, and they can go up and down by thousands of dollars between flocks. The farmers have a really hard time budgeting and predicting how much they’re going to be able to earn in order to make debt payment and pay their own bills, and often get into a credit crisis or everyday financial cashflow problems.

Katy Keiffer: Really interesting. Joe why do you think this is so? You had this quote in your piece, “Why would poultry companies want their producers to struggle? Wouldn’t they want to reward their good work and not bury them in debt?” As you point out, Tyson claims they want the best for their growers, that they do admit that they reward with financial incentives growers who upgrade, and we’re going to talk about upgrading all the time, . In your article, the couple that you profiled, the Crutchfields, they acquiesced to upgrade after upgrade, and it wasn’t until they were close to retirement age that they thought, “Oh my God, I can’t take out another loan for 250,000 dollars.” But the point is they went through all these upgrades, and their financial situation never seemed to improve. Just as they were peeling themselves out from under the last stone of debt, they were required to take on more. I find that just a fascinating cycle. I wanted you to go into that a little bit more.

Joe Fassler: To answer that question, I think the farmers need their supplier to survive and do well. If you ask Tyson (or, I’m sure, any other integrator) this, they will say, “We support our farmers. We rely on our farmers. We need them.”

Katy Keiffer: I’m sure.

Joe Fassler: Why that gets tricky is because of the system that Sally mentioned. Basically it’s a zero-sum game. Every cycle,–I think there’s five or six chicken growing cycles a year typically–the farmers who grow the most amount of chicken meat for the least expense will be compensated the most.

Katy Keiffer: So they’ll get more contracts, they’ll get better birds ….

Joe Fassler: Actually though, I think they’ll get a better price per pound.

Katy Keiffer: They get a better price per pound. In Chris Leonard’s book The Meat Racket, which I absolutely love and taught me so much, he talks a lot about the tournament system. And you know, sometimes if you complained, you might get lesser quality birds, for example, for a couple of cycles, to kind of teach you to mind your manners.

Joe Fassler: There’s this situation where there’s going to be winners every time, and they might be the same people sometimes, and they might not. But absolutely there are always going to be the farmers who are doing well, which in the industry’s eyes means growing the most meat as cheaply as they can.

Katy Keiffer: Right.

Joe Fassler: At the same time, there are always going to be people who don’t do as well. It’s like getting graded on a curve in college. There are going to be only a certain number of A’s, and it’s not that it’s a level playing field most of the time. There are variations in the type of feed, the quality of feed, and the quality of the birds. And so actually it’s not that everyone is starting on the same starting line. The reason it ends up being unfair a lot of the time is because of this zero-sum system. Add to that the fact that there will always be struggling because there are more farmers out there than the integrators need to have them all do well.

Katy Keiffer: Well, I think I want to stop for a second, and just point out that listeners who aren’t familiar with perhaps contract growing, the way it works, is that the companies own the birds, the companies own the feed. They supply the birds, they supply the feed to the growers, and then once the birds are grown, they pick up the birds, and deduct the cost of the feed from the ultimate price that the grower gets. Basically, the company is risk-free. I don’t think that the, yeah, the growers are only paid for the birds that survive. And of course there’s always some death rates there, but the company is basically risk-free, and the grower takes on all the risk, which is why this contract system is (I think to my mind anyway) fundamentally unfair. Right, Sally?

Sally Lee: Do you mind if I just jump in on the tournament piece there?

Katy Keiffer: Please do. Yeah.

Sally Lee: Because it’s a really important piece, and it has all these nuances that are actually being exported into other industries, so it’s really relevant to look at that a little bit. The company owns the birds, they provide all of the input to the farmer.

Katy Keiffer: Right, the drugs, food, yeah.

Sally Lee: The farmer is paid per pound of meat produced, and the company uses an equation so that they don’t quite deduct the cost of the feed from the final pay but they come up with this equation of how expensive the farmers were to the company, which we talked about. The reason why a lot of farmers get disenchanted and frustrated is because, while the company in a meeting says, “this is about how hard you work,” in the end their rank in the tournament is really determined by the company’s decisions and the company’s input.

I really like that analogy of being graded on a curve in college. But imagine that before the exam, everyone is given slightly different notes and slightly different slides to prepare from.

Katy Keiffer: Right.

Sally Lee: Some farmers are starting in the tournament at a significant disadvantage because of disease, because of just unavoidable biological risk in farming. And this tournament mechanism is a way to pass that biological risk on to farmers. They become sort of shock absorbers of that risk because of the zero-sum game.

Katy Keiffer: Right.

Sally Lee: It’s been called by economists a brilliant mechanism to solve a lot of problems in risk management in the industry, and a lot of other industries are picking it up.

Katy Keiffer: Yes, I’m sure. I mean I know they’re doing it throughout animal agriculture. They’re all adopting this chicken model. But Sally, one of the things that we’ve been talking about also is the constant upgrades that are required, and part of that is because of the advances in technology. But growers are rewarded, as Joe pointed out, with financial incentives for creating these upgrades or putting these new upgrades into their houses or barns.

Can you talk a little bit about that housing? And this is what I think is just so incredibly unfair is that every company has different requirements for their housing, so that means that somebody who was working for Tyson has to completely start from scratch (like rip out his infrastructure or change his housing) in order to work for another company. I want you to talk a little bit about that and the impact that has on how farmers and growers cannot go from one company to another, and thus remain in this system of indentured servitude.

Sally Lee: Yeah, and I think that the backdrop to those issues that makes it such a vicious cycle for farmers is that this is a very geographically-based industry.

You essentially have a geographical monopsony [a market situation in which the product of several sellers is sought by only one buyer] where farmers are very limited, so maybe there are only ten integrators operating in North Carolina. But because each company is not willing to drive more than a 50 or 60 mile-radius from its processing plant in order to take on new farmers, then you’re really limited to who is in the driving distance in order to get a new contract.

It means that there’s a total lack of competition for farmers. Companies do not have to compete for their farmers, and as a result they can establish these sorts of extreme requirements, like having their own specs for housing, or imposing really significant capital investments or upgrades whenever they want because they know that farmers can’t easily switch integrators.

It’s definitely true that each company will have their own preset standards for housing, so some companies want houses that are longer or wider than other companies. And if you are with one company (we’ve seen this scenario happen often), and maybe you’ve been in the business for ten years or so, but then the company has come back and changed the contract. You’re no longer making enough money to make your payment so you would like to switch to another company, and maybe you’re lucky enough that there is another major company in your area that could pick you up, but in order to make that jump, you’re going to need to put in another couple of hundred thousand dollars in terms of investments in the house specs, or it could be a different brand of heaters, a different brand of waterers, or computer system.

Katy Keiffer: Right.

Sally Lee: These kinds of changing requirements pose a really serious barrier to transition and is a significant indicator of the lack of healthy competition in this industry.

Katy Keiffer: Right, an that is probably one of the most fundamental ways that the company has so much control over the farmers that –once build to somebody’s specs, and nobody else is accepting those specs–you’re basically screwed. Anyway, thank you for pointing that out.

So okay, now lets move on to something a little bit more macro here. In an article that I just read in The National Hog Farmer, because I follow all the trades (just love those trade magazines!). It is written for the pork-producing industry, and it was an article about ditching the new Farmer Fair Practices Rule, whichwas signed by the Obama administration just before the end of his presidency. And in that article the following statement was made,: “The long-term impact of these proposed regulations is unknown and, if the current contract model becomes too risky from a legal or economic standpoint, they could significantly change the structure of the industry over time to one that is far less beneficial for the grower.” And then, (my emphasis here), “It conceivably could force companies to evaluate other production models that do not include contracting with independent family farmers to raise turkeys.” Is that a threat or a promise? I mean doesn’t that sound like a threat, people?

Sally Lee: Yeah.

Katy Keiffer: Joe is nodding.

Sally Lee: I believe it does sound like a threat, and it’s one that we see made to farmers often. Whether they’re saying, “Well, if we allow any type of accountability in the industry, then it will be too expensive for companies to contract their farmers.” Which is a very, if you think about that, it’s a very unfair premise: that farmers should accept being exploited otherwise they’ll lose their job.

Katy Keiffer: It’s economic blackmail.

Sally Lee: It would be familiar to any type of worker organizing as well.

Katy Keiffer: You know, even during the administration of Obama, they we’re trying to move towards anti-trust regulations to put on to the meat industry, and they never really got very farmer because of the unbelievable power of the food industry and the unbelievable spineless nature of our Congress who are all taking money hand over fist from these bastards.

What we need to see moving forward is some kind of anti-trust legislation that comes into play that limits the power of these integrators. One thing that struck me about that, though, is the poultry industry is pretty well automated as it is. I mean that’s part of the great success of the poultry industry is that you can have poultry houses, and also have another job. You can have poultry houses, and work other types of farming on your land because they pretty much run themselves.

All you have to do is walk around, and make sure that your feeders are dispensing feed, your waterers are dispensing water, and you don’t have too many dead birds on the floor. It’s a highly automated industry so isn’t that like sort of saying we could go further and just basically get rid of all of you guys? And would that be a plus or a minus for the industry when it comes down to it from an economic standpoint? Is it better to keep the grower in a state of indentured servitude? Or is it better to just go on full-on automation, and have one guy with a bunch of video cameras? What do you guys think?

Joe Fassler: It’s really hard to say, and Sally I’m curious what you think. One question that I have is, if these companies were to go fully automated, would they still host these facilities on people’s private properties and have them operate them? Or would they want to do it in something like a slaughterhouse where they own it? It’s not independent but brought into the company’s structure.

I mean, I did speak to a chicken industry representative recently who said that one of the challenges would be real estate. In other words, if you want to be growing billions of chickens a year, you can’t necessarily do that on land that any one company owns. At the same time, the farther away that you get from the human interaction with the creature, the less and less sense it makes. I’ll be actually watching this with a great interest. Sally I’m curious what you think about that.

Sally Lee: One thing that’s interesting is that, especially in the ’60s and ’70s, right as the contracting boom was building up, some company did experiment with owning their own houses and hiring employees to work those houses. It was definitely land that was the problem, and real estate expense. Also, if you think about the fact that many farmers leave the system and new farmers come in and have the responsibility to build brand new houses, then they face the costs of maintaining that equipment, the burden that the companies did not find to be profitable.

Katy Keiffer: Right.

Sally Lee: And there are many biological risks that the companies also have externalized to the farmers through these contracts. There are many benefits to the company of putting that whole situation onto the backs of farmers through a contract and extracting the most profitable aspects of it.

Katy Keiffer: I think so too because, let’s remember that the grower owns the shit. They own the litter, and the soiled hay and the dead birds: all of that stuff. I noticed somewhere, I can’t remember if it’s something I read from you Joe or somewhere else, that the contractors have to have a refrigerator to store the dead birds in. And I know that in the past there have been lawsuits. There was a lawsuit in the Chesapeake area against Tyson, I think it was, because the guy had so much poultry shit, and litter, and dead birds that it was like basically a health hazard for these neighbors. And yet Tyson won the suit, by the way. I think it’s really important to emphasize that the grower owns all of the external cost, and that (to me) makes it seem very unlikely that the industry will become fully automated. But it is sort of an interesting premise to bat around for a second.

Joe Fassler: Yeah, or would the economics of it change if it was fully automated?

Katy Keiffer: Right.

Joe Fassler: Would there be less risk? I mean (as Sally is saying) when it comes to slaughter, the economics are pretty straightforward because you get the birds in and the meat comes out. But when it comes to raising livestock, it’s really that biological risk that creates a lot of this uncertainty. Are there ways of automating so intensely that you can push back against some of those innate biological risks? Probably not. But I wonder if technology will change the game there somewhat.

Katy Keiffer: I can imagine somebody like a Tyson buying a relatively small piece of land and building a skyscraper on it that houses two million birds. I mean, why not? Like why not? And then you have a pit that all that stuff goes down into, you know like pretty much the same thing.

Joe Fassler: And there might even be environmental advantages to doing it that way in a sense because you’re not shipping birds from, you know, far away.

Katy Keiffer: Indeed, it’s right next to the slaughterhouse, and then you also reduce your risk of avian flu and other issues that come with having people walking in and out of a facility–I mean, the bio-security for these places is really intense, I know that from having done the research.

Sally, explain this to us. How is it possible that growers have so little legal protection from these predatory practices? What happened?

Sally Lee: Well, there’s one law that we already have on the books called the Packers and Stockyards Act.

Katy Keiffer: Right, oh good we’re going to talk about that one.

Sally Lee: Yeah, it was passed in the ’20s. There’s one part of it that talks about anti-trust measures but the rest of it should be the rule book for integrators, and large companies, and meat packers But for a long time, however, many of our federal judges have been interpreting that law in such a way that if a company does something unfair against one farmer, that farmer has to prove that what the company did to them harmed all the competition in the industry. That their claim essentially satisfies the anti-trust component of the Packers and Stockyards Act in order for the act to be enforced.

In order for there to be any enforcement that the company should do something differently. Many farmers have brought very legitimate cases to court that have gone all the way up to being considered by the Supreme Court even that demonstrate documented damages, losses, even losing their farm as a result of unfair and discriminatory actions on behalf of the company. But these have been dismissed, and right now there is a series of rules that have been proposed by the USDA called the Farmer Fair Practices Rules, and these were put out at the end of the Obama administration. Part of those rules clarifies that the Packers and Stockyards Act should not be misinterpreted in the way that it has been in the past decade, and that it actually is there to protect farmers from these unfair practices. We desperately need that. We’re at a place right now where we need very basic rights enforcement for farmers, business rights enforcement, because the industry has gone so far in the opposite direction. It’s very one-sided.

Katy Keiffer: Yeah, absolutely. Well, we’re going to do more about the whole Fair Practices Act because obviously that’s going to go away now that we have Sonny Perdue sitting in the agricultural seat, and he will sail through his confirmation.

Besides the trade magazines where you would expect to see propaganda that promotes the corrupt status quo, I also follow a page called The Food and Farm Discussion Lab on Facebook, where virtually every day, I am amazed by the animosity that is directed towards progressive food movement people. That we are somehow meddling in their business and potentially causing problems for them by saying that we don’t like factory farming. There’s a lot of stuff about that. They aren’t fazed by Monsanto. They love GMO crops, and they think factory farming of animals is something that PETA thought of basically to screw them. And they’re all active farmers. They’re all pretty smart people, and they’re not industry. What explains this divide between your average farming guy and those of us who feel like (A) farmers are being screwed, and (B) we don’t like the kind of food that they’re being required to produce? Like what is that?

Joe Fassler: I think part of it is the cultural schism that you’re seeing in our culture right now, which is this divide between (generally speaking, of course) the urban centers and the rural heartland. Siena Chrisman has written well about this for Civil Eats recently, It’s one thing to say, as many farmers do, that something like factory farming has some issues. It’s another thing to not be directly involved in the production of food and point that same finger. I think there are some issues there. I remember speaking to Kathleen Merrigan, who’s undersecretary of agriculture.

Katy Keiffer: Under Vilsack in the first under Obama term. She’s been a guest.

Joe Fassler: She said people do not understand the way food is grown in this country and it starts with empathy. You have to understand that there are people out there trying to make a living, and people need to first know the facts and not have a romanticized view of the food system before they can start to critique it. And I think that’s where we come in as journalists, and one thing my publication is trying to do is just to raise the sea level of basic food literacy.

Katy Keiffer: Right.

Joe Fassler: There are lot of challenges to that but I think that that would go a long way. Beyond that, we’re talking about the people in these situations sometimes who get into situations that look predatory. They’re extremely hard workers.

Katy Keiffer: Yes.

Joe Fassler: Farmers don’t have so many options in their regions to make a living. There’s a million reasons for that on a policy level, and so I think they’re protective of their way of life. I think it makes a lot of sense, and one thing I would love to see happen is not to just have these sort of two tribes speaking different languages but to look at the gray between the black and the white, and see what we can do to have meaningful reform.