Joe Dietsch

We’re eating at street-corner stalls and food trucks, in front of the TV and at the grocery—everywhere but restaurants. They might not be here when we get back.

In a week, The New York Times would run a rave review of FieldTrip, a rice-centric little place in Harlem, New York City. Crowds of eager diners would suddenly descend, and the Sweetgreen chain, as well as the folks at Rockefeller Center and developers around the country, would get in touch about possible alliances.

But at 5:30 on a weekday before the review, owner and chef JJ Johnson did what he’d done since the restaurant opened three months earlier: He greeted the two tables of two who were having an early dinner, tasted everything the kitchen had going, dropped some supplies on a shelf, and fretted.

The 35-year-old Johnson had cooked at two high-end restaurants until they went out of business—The Cecil, a fine-dining establishment nearby, and Henry, a short-lived place in a restaurant-laden neighborhood called the Flatiron, where he was a partner. FieldTrip is as different from them as a restaurant can be: Its short menu is built on Johnson’s obsession with varieties of rice, priced to feed a customer for $20, served in disposable dishware and eaten with a compostable spork. There is no décor to speak of, beyond basic clean and bright. Forty percent of his business is take-out and delivery.

FieldTrip’s chef/owner JJ Johnson at his fast-casual, rice-centric restaurant in Harlem, New York City.

Tricia Vuong

After years in the culinary fast lane—Johnson was a semifinalist for the James Beard Foundation rising star award and made multiple 30-under-30 lists—he has retooled his aspirations. FieldTrip is within walking distance of far more familiar brands, including Popeyes, McDonald’s, and KFC. He wants to offer an affordable but nutritious alternative, to build a brand that might someday support 10 outlets if things work out well. Anything more than that is a pipe dream, and he is no longer interested in dreams.

“What I want,” he said, “is butts in seats.”

The restaurant industry is in a scary place, one that fairly guarantees heartbreak. Restaurant traffic was “flat” at the end of 2019 and “sluggish” the year before that, according to The NPD Group, a research firm that tracks how often we spend money at five types of businesses: fine dining, midscale, casual dining, retail, and, the biggest category, with 62 percent of the pie, quick-service restaurants (QSRs). Quick-service and retail qualified as “relative bright spots,” according to NPD, and casual places managed not to endure a fifth straight year of losses. But full-service restaurants dragged everything down: “Visit declines in the full-service restaurant segment continue to prevent the industry from growing.”

Hardly a bull market, and it only gets less reassuring from here, because there’s no consensus on the consequences. The NPD group says restaurants are closing. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) says they’re opening: In the first half of 2019 the BLS logged about 40,000 more “food service and drinking establishments” than there were just four years ago, a jump from 526,387 to 568,870.

The National Restaurant Association says that 70 percent of America’s restaurants are owned by individuals, not operating companies or venture capitalists. Left, making rice bowls at FieldTrip.

Tricia Vuong

The credibility gap may stem from different definitions of “restaurant”—or worse, it could mean that places are opening at a faster pace than they’re closing, which surely qualifies as a case of mass denial. The BLS data hardly scream stability, showing a dip between 2012 and 2013, and another that started in 2017 and isn’t over yet.

A perfect storm of variables, many of which have little to do with food, has already changed restaurant culture—and the coming decade may make the current disarray look like nothing.

Chefs and restaurateurs on both coasts take a dim view of the future, not because of the numbers but because of their own experience, going to work and talking to their peers: Too many restaurants open and then close too fast, after months, not years. And closures are an equal-opportunity phenomenon, nationwide. If you live someplace that grows or raises the food these city chefs sell, you might want to make sure your local Applebee’s is still open before you pile the family in the car and head over—the chain just announced a new growth strategy, but it centers on catering and delivery, not restaurants.

That sound you hear is doors closing, no matter where you live or where you go out to eat.

If this were the stock market, an analyst might say we’re in an inevitable correction, a healthy if unnerving return to reality, which means fewer but more sustainable places to eat. If we were talking evolution this would be survival of the fittest, who get even more fit because there’s less competition for every dining dollar.

Experienced restaurateurs say it’s a paradigm shift—new people, new sources of money, new expectations, most of them unrealistic, and a new generation of diners who don’t consider seats and service a priority. As more businesses look for more ways to feed us, today’s definition of “restaurant” may take its place on the shelf right next to the typewriter.

Restaurants are an at-risk population even in more stable times, in part because their owners embody the American ethos of the independent, can-do spirit, which means they have no safety net. The National Restaurant Association (NRA) says that 70 percent of America’s restaurants are owned by individuals, not operating companies or venture capitalists—people who don’t have the kind of deep pockets a bigger company might. A national chain like the ones in Johnson’s Harlem neighborhood can amortize risk over thousands of units, the stronger ones compensating for a location that’s having a slow month. A singleton like FieldTrip is more vulnerable.

Back of house at Huckleberry Bakery and Café in Santa Monica, California.

Joe Dietsch

The logical, if unwelcome, next step might be further consolidation, as corporate investors gobble up promising small businesses or simply outlast shakier ones—and in fact, NPD blamed a 2018 dip in quick-service outlets on a decrease in the number of independents. In the tradition of Big Ag, Big Pharma, and Big Tobacco, we could be headed into the era of Big Menu; some complain we’re already much of the way there.

None of this seems to concern the NRA, which sees a boom food economy ahead, with projected annual sales of $1.2 trillion by 2030, up from a projected $863 billion last year.

The question is where that $1.2 trillion will be spent. Chip Wade thinks there are too many options; something’s got to give. “You can elevate the conversations above restaurants,” said Wade, president of New York City’s Union Square Hospitality Group, with its group of legendary fine-dining restaurants, after years spent at Darden Restaurants, home of the popular Olive Garden and Longhorn Steakhouse brands, and at Red Lobster. “There may simply be too many food establishments.”

That has even seasoned restaurateurs staring down the apocalypse. “There’s no protection for a well-intentioned restaurant anymore,” said Josh Loeb, co-owner of nine successful restaurants and retail shops that make up the Rustic Canyon Family in Santa Monica, California. “There’s no middle ground. You’re either wildly successful or you’re closed.”

And yet people keep opening restaurants, on the assumption that bad news happens to someone else. Gadi Peleg, owner of four Breads Bakery locations and two fine-dining restaurants in New York City, came to food from the world of finance. He sees an unnerving similarity.

In 2018, an NRA report said 37 percent of its members ranked hiring as their biggest challenge. Pictured: Back of house at Breads Bakery’s Union Square location in New York City.

Tricia Vuong

“The problem with bubbles,” he said, “is that you don’t know you’re in one until it bursts.”

If you’re intrigued by the notion of an artificial-intelligence cook making a meal that you enjoy in the comfort of your own home—no driving, no parking, no combing your hair—you might not mind the end of the brick-and-mortar era. If you like your neighborhood café, wherever that neighborhood might be, you have cause for concern.

Not that we get to vote on the outcome here. A perfect storm of variables, many of which have little to do with food, has already changed restaurant culture—and the coming decade may make the current disarray look like nothing.

One thing for sure: It’s safe to say that as you read this a restaurant owner, somewhere, is staring at a screen full of numbers, weighing options and wondering how things got this crazy this fast.

Being a chef has become an aspirational calling, kind of like being a movie star—with a similar blind spot about the percentage of failures.

—

Too many people want to be chefs and own restaurants. For that we have new media to blame, along with our intersecting love of food and the meteoric-rise narrative. Instagram debuted in 2010, so, for the sake of shorthand, let’s refer to the last 10 years as the Instagram decade, though it’s hardly the only medium that embraced and exploited food: Restaurants and chefs showed up on countless television shows, from a South Korean Zen Buddhist nun on “Chef’s Table” to Guy Fieri on “Guy’s Grocery Games,” as the number of outlets grew and demanded ever more original content. We tracked restaurants in legacy publications and on influencer blogs, and grabbed a kimchee quesadilla from L.A. chef Roy Choi’s Kogi truck to eat while we watched his alter ego in the movie “Chef.” Culinary school enrollments went up, even as those schools expanded their curricula beyond traditional culinary classes, because the world is not elastic enough to accommodate that many more restaurant chefs.

All that noise attracted customers and rewarded the ones who got to a new place first to post photos of opening-night dishes. Being fickle was imperative; a regular, a diner who prized loyalty to a favorite place, clearly lacked initiative.

It is easy to get caught up in the frenzy. The Pew Center says that 96 percent of U.S. adults own cell phones—but the number that’s really taken off since 2011 is the owners of smartphones, up from 35 percent in May, 2011, to 81 percent in February of last year. As we enter the second decade of this new information age, most of us have access to whatever a chef chooses to share, from an Instagram post of today’s special to a running commentary on the chef’s pets, travels, political opinions, awards, and family. There have always been stars, but not so many, not so quick to ascend, not elbowing each other for a shot at the limelight.

And if you exhibit the slightest interest, an algorithm somewhere starts sending you more information, which you click on, which gets you more information, tailored to your personal preferences. We are the high-speed descendants of fans who pored over movie magazines 100 years ago.

That’s not a random analogy. Being a chef has become an aspirational calling, kind of like being a movie star—with a similar blind spot about the percentage of failures—and young cooks with stars in their eyes are in a hurry to be the next big thing. They make for an impatient, ill-prepared workforce, unwilling to work their way up the kitchen ladder. In 2018, The New York Times cited an NRA report that said 37 percent of its members ranked hiring as their biggest challenge, compared to 15 percent only two years earlier.

Jody Williams (right), co-owner with Rita Sodi (left) of New York City’s Via Carota, says the first thing she does with new sous chefs, who are responsible for placing food orders, is slow them down.

Jody Williams is co-owner with Rita Sodi of three places in New York City’s Greenwich Village (Sodi owns I Sodi on her own), with a fourth planned for this spring; their small café, Buvette, already has two international outposts with two more on the way. The first thing Williams does with new sous chefs, who are responsible for placing food orders, is slow them down. “I give a new sous chef a marking pen,” said Williams, who last year shared the James Beard award for Best New York City Chef with Sodi, “and I tell them, you’re going to write down the price of everything in this kitchen for the next two weeks. How much is an egg worth? Write it down, on the egg. Understand it—because you can’t manage what you don’t know.”

“We pay attention beyond guests and cooking, to numbers and prices,” she said. “You’ve got to know your books, know how much a seat makes. One chair at Buvette, what does it make in a year, what is it worth? You have to have a feel for it so you can do the math in your head, and then you verify it every month.”

Hardly the fun part, unless your idea of fun involves staying in the black.

But too many people enter the field based on its public image, which is a lot more attractive than reality turns out to be. “When we sit at one of my restaurants it’s alluring and fun—and that represents about one percent of my life,” said Gadi Peleg, who starts each morning at a communal table at his flagship bakery in New York’s Union Square, to monitor how things are going. “The other 99 percent I’m looking at grease traps, making sure the bathrooms are clean, dealing with employees who don’t show up. I get my hands very, very dirty. That’s the reality of the restaurant business. Any illusion of ‘I’ll hire people and it’ll go great’ isn’t reality.”

“You’re on call more than a doctor, working all the time, you’ve dedicated your life completely,” he said. “You never won’t work, or I haven’t figured out how to. It never stops.”

Front of house at Gadi Peleg’s flagship Breads Bakery.

Tricia Vuong

Los Angeles baker Roxana Jullapat blames social media for another seductive, if damaging, illusion: that there are hordes of eager customers dining out several nights a week, surely enough to support a new venture. Jullapat owns Friends & Family café and bakery in the East Hollywood neighborhood of Los Angeles with her husband, chef Daniel Mattern. After 20 years working at some of the city’s best-known restaurants, and being a partner at one place that closed, she knows the city’s daunting secret.

“Social media, the stratosphere of influencers, make it seem like everything’s booming, but the places that are bubbling all the time you can count on one hand,” she said. “What we’ve always said is that L.A. is a small restaurant market. The group of consistent diners is really very small.”

“When we talk casually among colleagues, ‘did you hear that so-and-so closed after nine months?,’ some short period of time, we always say, ‘People think they know L.A., but they really don’t,’” she said. “We wish people felt the need to go out to eat more, not just on the weekend.”

Baker Nicole Rucker opened Fiona, a bakery and café, in November 2018, and closed only nine months later, despite a Los Angeles Times review that praised her “assured virtuosity” and said, “Rucker reigns supreme among Los Angeles pie bakers.” She recalls the stream of bloggers, influencers, and mere civilians looking to increase the size of their social media platforms—and holds them partly responsible for what happened to her.

After closing her bakery and café, Fiona, Nicole Rucker will open Fat and Flour as a permanent stall at Grand Central Market in Los Angeles.

Joe Dietsch

“It’s embarrassing we’ve allowed it to get this far, we, as a culture,” she said. “Look how it’s inflated all of our notions of lifestyle—beauty, all the categories—into a very blown-out culture of ‘show me, show me, show me.’” Customers ordered food at Fiona, took photos, and never took a bite; they were after likes, not a dining experience. Given their priorities, they were never coming back.

The new breed of investor, the one who sees food as a potential gold mine, defines success as bigger profits in a shorter time frame.

—

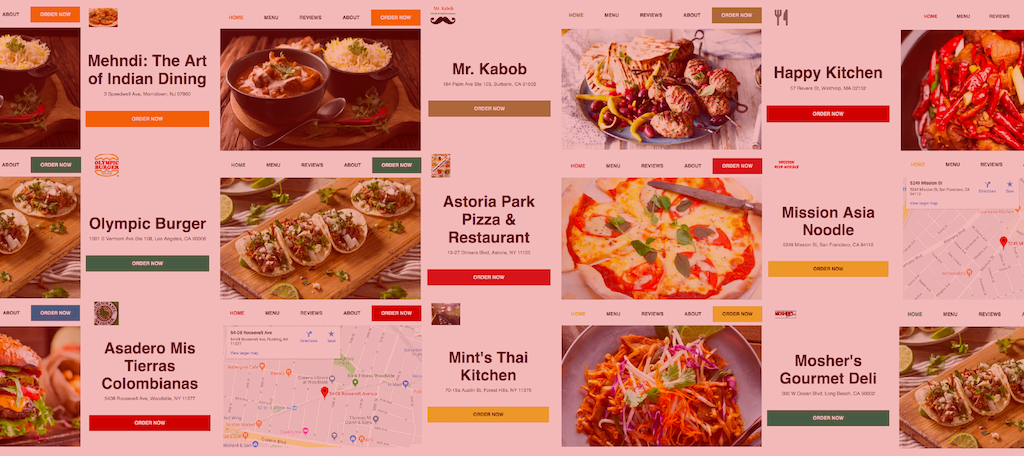

Venture capital is throwing money at the end of restaurants. CloudKitchens, a start-up from ex-Uber CEO Travis Kalanick, has received $400 million from Saudi Arabia’s sovereign-wealth fund, according to The New York Times. Reef Technology, a Miami start-up, has funding from SoftBank, the Tokyo-based multinational whose previous, oft-troubled investments include Uber and WeWork. And Kitopi (short for Kitchen Operation Innovation), based in Dubai and New York City, is about to spend $60 million to expand its U.S. business.

The money’s for ghost kitchens, volume operations designed to cook and deliver multiple cuisines from a single, massive kitchen. The latest iteration, from Kitopi, is the ghost kitchen as remote franchise, contracting with a brick-and-mortar restaurant to make and deliver its dishes. Whatever the model, big money is banking on a stay-at-home future. The old-school argument about who wants what for dinner will be resolved by a driver who pulls up to your home with one Chinese meal, one Italian, one vegan, and one hot-chicken plate.

Huckleberry Bakery and Café’s ingredients are all organic—attractive to diners, as long as they don’t make a meal too expensive.

Joe Dietsch

This is not the type of investor who funds the traditional restaurant, in which a place opens, builds over time, establishes a loyal clientele even as it attracts newcomers, and stays in business for years if not decades. In that version of the story, investors assume they’ll see a small payback in about five years, and in the meantime they’ll always be able to get a great table, no matter how busy the restaurant is.

The new breed of investor, the one who sees food as a potential gold mine, defines success as bigger profits in a shorter time frame. Patience is not part of the high-finance, cut-and-run formula, so places close, often before they’ve found their footing, if profits fail to meet projections.

“At a certain point in the last few years,” said Josh Loeb, “restaurants became a sexy thing to invest in from big venture money—‘this bakery or coffee shop is going to expand, so we’ll put seed money in.’” He and his wife, baker Zoe Nathan, regularly field—and turn down—inquiries about cloning their popular Huckleberry Café in Santa Monica.

Today’s restaurant investors want bigger profits in a shorter time frame. Above, the pastry case at Huckleberry Café.

Joe Dietsch

But it’s easy to get caught up in the excitement, especially when a chef already has a public profile—is herself an exploitable commodity—and investors are prepared to underwrite a massive roll-out. “Carla Hall did the most honest interview when Carla Hall’s Southern Chicken closed in Brooklyn,” said Peleg, of the “Top Chef” alumna’s first stand-alone restaurant, which opened in June, 2016 and lasted just over a year. “It’s a lesson I’ll have forever in this industry: she said she was focused on the 200th location before the first one opened. That’s a powerful comment.”

“People who pitch to investors have to present concepts where the graph runs bottom left to top right,” he said. “I get the economics of scale, but scaling used to happen more organically—not so deliberately and on a PowerPoint before you’ve put one thing in a skillet.”

The same dynamic can show up in smaller partnerships, often with the same abrupt, early end. An operating company approaches a chef like JJ Johnson, who has more ambition than cash, and offers him more money than he can possibly raise on his own. In exchange, Johnson said, he chips in his “intellectual property,” the creative ideas that make him a draw.

“When people invest in a tech startup they figure they have to fund it for three years. A restaurant gets three months. But you’re not going to know your business in the first three months, c’mon. Why can’t we be well-funded and smart?”

Henry, which opened in New York City in late 2017, was already in trouble the following summer, when Craveable Hospitality Group approached Johnson with what sounded to him like a good idea. He didn’t have to put up money he didn’t have, he would be a partner, and his food was supposed to save the place, which implied a level of freedom in the kitchen. In practice he felt more like an employee—and by the time the group closed the restaurant for good, 11 months later, he had come to understand “the trade-off for cash, that’s the risk you take, you give up the right to make decisions.”

Craveable Hospitality did not respond to several requests for comment.

Chef Michael Cimarusti, co-owner of the Los Angeles restaurant group that includes both the Michelin-starred Providence and the fresh seafood joint Connie and Ted’s, refers with dismay to a “gold-rush mentality” and doubts he would be able to sustain a new business in today’s climate.

Chef Michael Cimarusti, who won the James Beard award for Best Chef, western region, last year, started out in his teens as a dishwasher. He went to culinary school, studied in France and worked in other people’s restaurants for over a decade before he opened Providence. Not many of today’s young cooks have that kind of patience.

Joe Dietsch

“The level of speculation going on in L.A. is insane,” said Cimarusti. “Lots of people invest lots of money, throw those doors open and expect to be crushed by the crowds,” he said, “and it doesn’t happen. You can throw $20, $30 million at a place, roll the dice and hope it all goes well—or do it for less, and build something that will last.”

Or you can miscalculate and have to pull the plug too soon. Jullapat said the “first and foremost” reason new places fold is that they run out of money before they start seeing profits, thanks to misguided notions of how long it takes to get to healthy. “Places are undercapitalized,” she said, “because people completely underestimate what they’re going to need. They think of opening costs—let’s build it, let’s get through the inspections—and then you don’t have enough cash. You have to be prepared to be under budget for a couple of months. And that’s a lot of money.”

Johnson blames Henry’s demise on that kind of unrealistic timetable. “When people invest in a tech startup they figure they have to fund it for three years,” he said. “A restaurant gets three months. But you’re not going to know your business in the first three months, c’mon. Why can’t we be well-funded and smart? ‘Let’s get behind this person and really support him for three years, let’s have a $1.2 million loss cap, and then, if we don’t see progress we’ll have to cut it off.’”

“We’re creators of beautiful things, but we also have to stay in business. You have to make things that people want to eat—and there’s a section of the public that’s adventurous, but that’s not the general rule.”

Nicole Rucker can rattle off every obstacle she and her two partners faced at Fiona: a bad-luck location, a neighborhood that didn’t step up, confusion over whether Fiona was a bakery or a Vietnamese café, thanks to chef Shawn Pham’s menu. But the reason it failed, she said, is simple: “Not enough money. We were underfunded.”

Chefs clamoring for attention, diners on the prowl, and bottom-line investors who don’t appreciate the idiosyncrasies of the business: not a secure environment.

—

Lemmings, those little rodents who travel in herds, do not regularly commit suicide by playing follow the leader off a cliff. They do practice their own form of population control, which can mean a watery grave, but not by choice. When a herd gets too big, a group of them sets off in search of a new home, and if they have to cross a body of water they jump in, because they know how to swim. Or at least some of them do. Some drown, and that, over time, has congealed into the suicide myth.

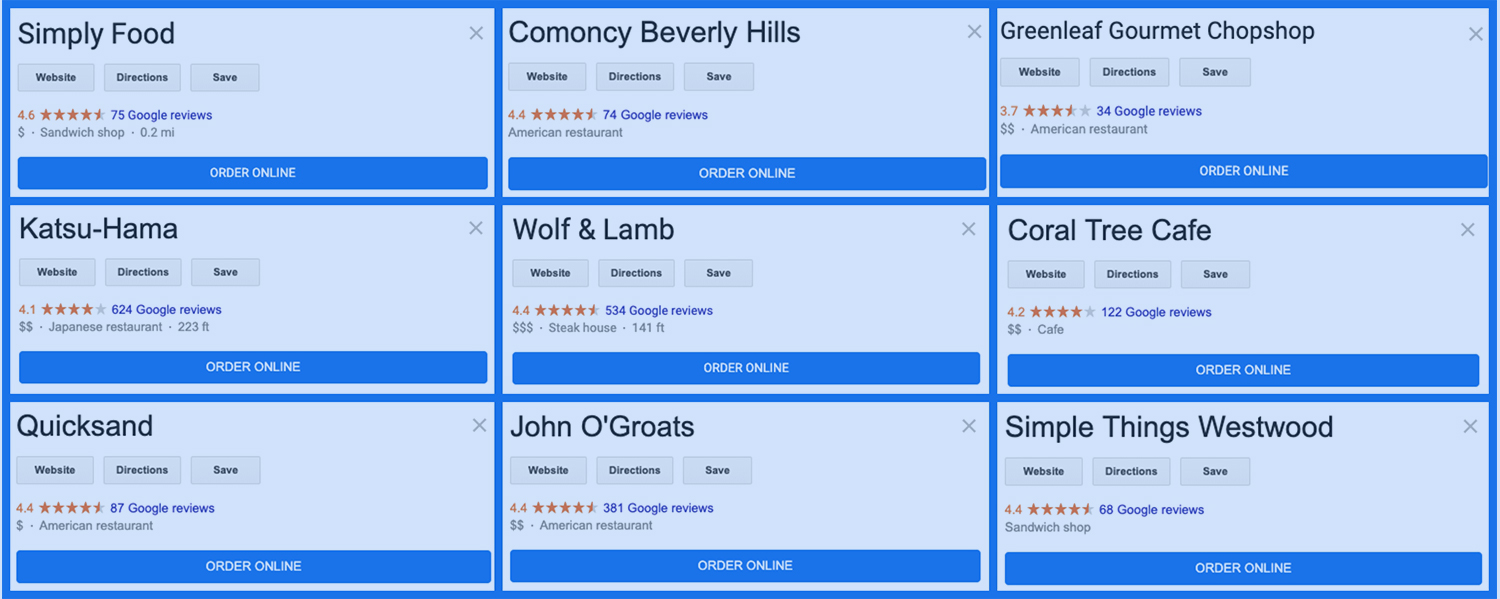

That mentality, translated to restaurants, means trends: a bunch of newbies see a promising food concept and follow that splinter group to what they hope will be a happy, profitable new home, having learned nothing about the dangers of too many lemmings in one place. They chase replication instead of innovation, figuring a proven concept is safer than a new one, until they find themselves at the edge of a lake some will not be able to cross.

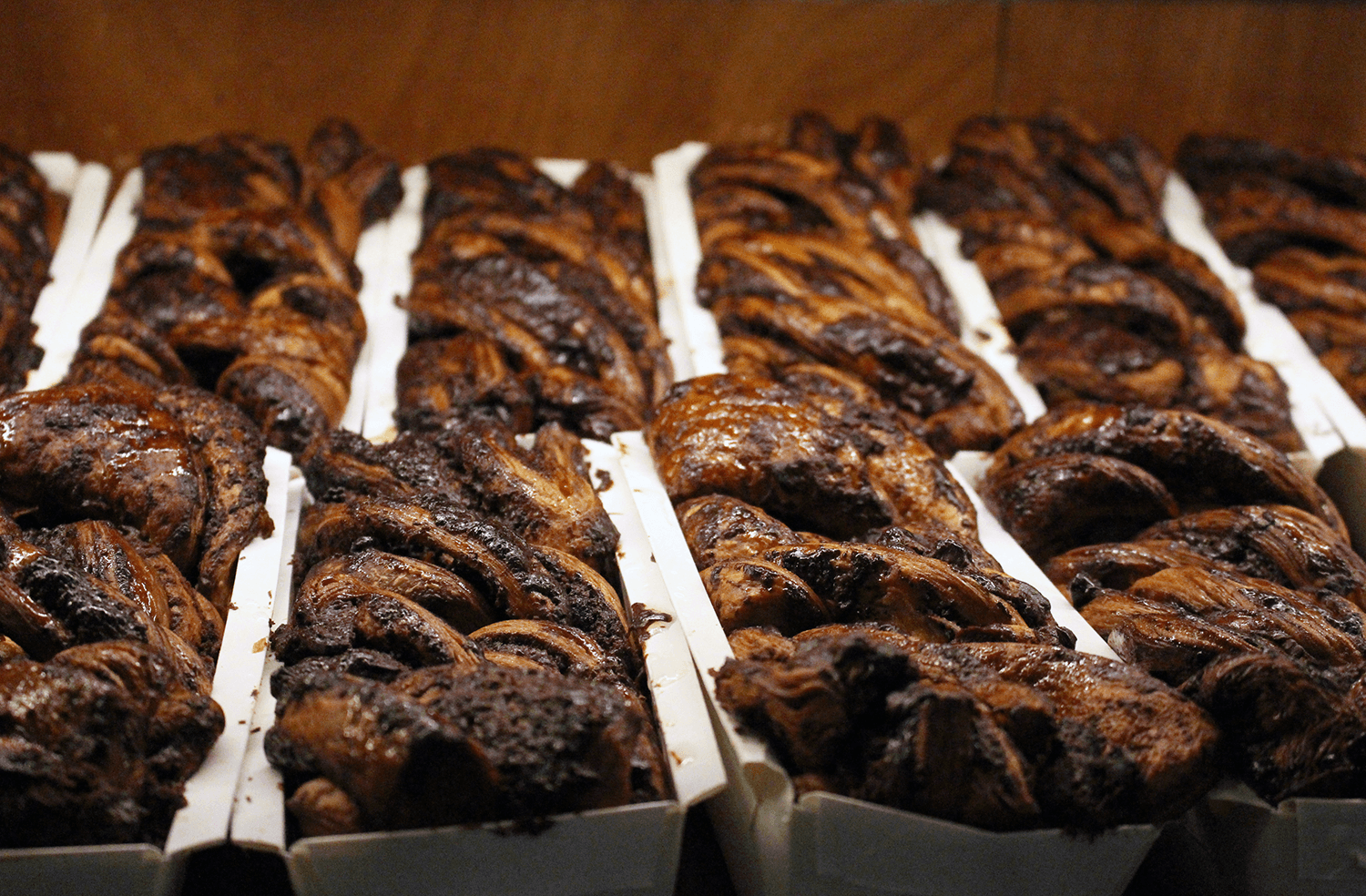

“I see pockets of little bubbles,” said Peleg, who believes that too many of any specialized business guarantees attrition. “It seemed a couple of years ago that all of a sudden every block had a cupcake concept in New York City, the great craze. But how many cupcakes do you really need, popping up everywhere?”

Not as many as there were. “Now I don’t know if you can get a cupcake in New York City,” he said, exaggerating for effect, “and the ones that remain are the ones that were here before the bubble.” Magnolia Bakery, made famous by the television series “Sex and the City,” has expanded to Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C.—and the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, and more, and if there isn’t one on your corner you can order online.

After New York Magazine named Breads Bakery’s chocolate babka the best, they went from selling 20 to 30 to thousands a day

Tricia Vuong

At the other end of the spectrum, Crumbs Bake Shop, which opened in 2003, was at one point the largest cupcake business in the U.S., a beacon of success for hundreds of imitators who would enter, and swamp, the market. As the cupcake trend crested and began to fade, as trends do, the company took a nosedive, closing all its stores on a day’s notice in 2014. A few stores re-opened, briefly, but there is no second act in food trends. By 2016, Crumbs was gone.

Cautionary tales like this seem to have little impact on the next wave, though, and Peleg marvels at people’s faith in their ability to be the exception that proves the rule. “I never heard the word poke in my life,” he said, referring to a Hawaiian raw-fish preparation that has inspired countless quick-service restaurants. “I went to one once, and I thought, okay, this is fresh, this is valid—but then there were 30 of them. We may be at the end of that wave.”

And yet being too different can backfire as well. Successful chefs say it’s important to strike a balance between giving people want they want right this minute, the passing fancy, and serving proven favorites.

“We’ll be slammed with orders from Postmates and Uber Eats in the back, and two tables are full in the front.”

“Look at your sales,” said Jullapat. “Every restaurant I’ve ever worked at, the chocolate dessert is always the best seller. We’re creators of beautiful things, but we also have to stay in business. You have to make things that people want to eat—and there’s a section of the public that’s adventurous, but that’s not the general rule.”

—

The chicken-and-egg question is, Which came first, dining options that aren’t restaurants or customers looking for new ways to get fed? The fallout’s the same, with restaurants wedged into the shrinking space between delivery and grab-and-go, facing a painful truth: Much of the time, we either can’t be bothered to get up and go out to eat, or we can’t be bothered to slow down and take a seat.

As our homes turn into sophisticated entertainment centers, the old notion of a sad sack slumped on the couch with cold pizza (offspring of the sad sack slumped on the couch with a foil-wrapped TV dinner) has given way to a new reality. We can order a great meal from a favorite restaurant via a delivery service, or from meal suppliers that didn’t exist 10 years ago—or did, but have since upped the quality of what they sell.

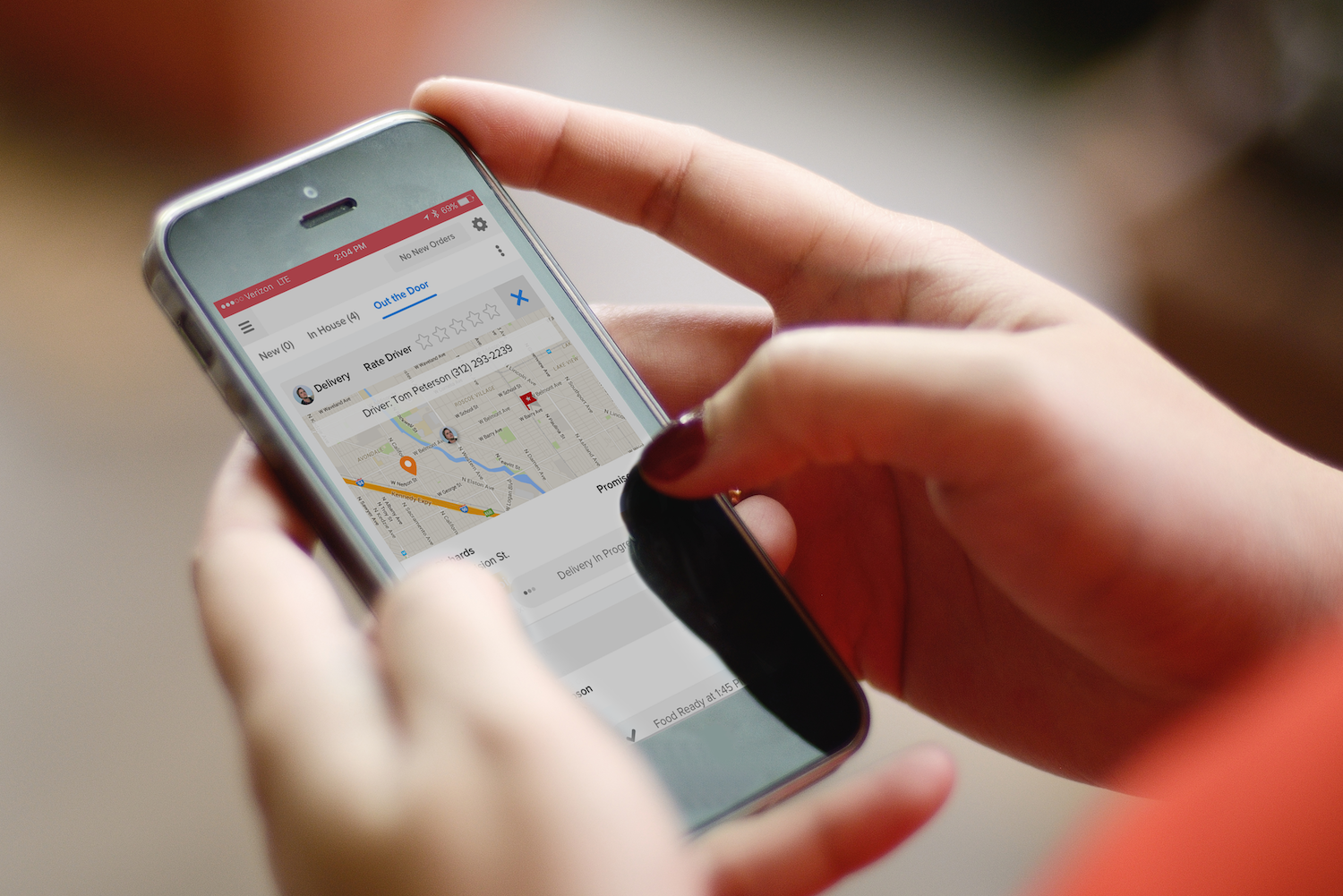

Delivery is still a small piece of the dining-traffic pie, but it’s distinctive because “it’s one of the only major sources of growth,” as David Portalatin, an NPD vice president, told Nation’s Restaurant News, “and everybody is starting to get into it.” The group’s research showed that 2019 digital delivery orders were up 16 percent over 2018—and the NRA estimates that nearly half of all take-out and delivery orders are made by customers who are under 35 years old, so it feels like the wave of the future. QSR magazine, which covers quick-service restaurants, cites a report from L.E.K Consulting predicting that delivery sales will outpace restaurant revenues over the next four years, by a factor of three.

Food doesn’t always travel well, so kitchens have to retool the menu to make their remote and take-out customers happy.

Joe Dietsch

While delivery sounds like a great way to increase sales—expansion without expanding—it’s not that straightforward. There are three ways to do it, all of which cost money: a restaurant can set up its own delivery system, use an outside service that takes orders and collects payment but requires the restaurant to deliver, or use a full-service system that takes a higher fee to deliver to the customer’s door. Delivery apps charge restaurants from 10 to 35 percent, cutting into potential profits, and restaurant owners face the nagging worry that delivery cannibalizes existing business. If the person eating a burger at home used to sit at the bar, the restaurant’s making less, because part of the check goes to the delivery service. And that customer didn’t order an alcoholic drink, further cutting into the restaurant’s profits.

Food doesn’t always travel well, so kitchens have to retool the menu to make their remote customers happy. At Tallula’s, Rustic Canyon’s Mexican place in Santa Monica, burritos show up on a separate delivery menu, but not at the restaurant, because they seem “a pretty solitary thing,” said Loeb, better for watching a football game than for sharing a meal out. The group’s Asian restaurant, Cassia, has created an offshoot, Cassia Rice and Noodle Kitchen, whose menu is available only by delivery or to go.

“Delivery food is food that can travel, so you have to narrow down the offerings,” said Jullapat. Not bothering is not an option, given the sales potential. “The trend sure is up. This world is constantly reinventing itself, evolving. It’s maybe 5 percent of our business, maybe more, and there’s a bunch of take-out.”

Ancillary businesses—delivery, catering and wholesale accounts—keep Friends & Family healthy. “We’ll be slammed with orders from Postmates and Uber Eats in the back, and two tables are full in the front,” said Jullapat, who also supplies baked goods and breads to about 30 cafes on the east side of the city. “We wouldn’t have been able to pull it off if it’d been just sit-down, or we would have had to downsize in the first year.”

Portable food, like the kind you can grab and go at L.A.’s Grand Central Market, appeals to our multi-tasking culture.

Joe Dietsch

Portable food appeals, in our multi-tasking culture, because linear behavior—I drive, I park, I order, I eat, and then I go home to my landline phone—has been replaced by a polyphasic model. Nobody’s sorry to eat and run anymore, but rather, proud of it. Ten years ago, the Kogi Korean BBQ truck was a Los Angeles novelty. No more, not when there are pop-ups, outdoor food events, and more and better street food than ever before. Tasty distraction is everywhere, and, while it contributes to a vibrant food scene, there’s a painful irony—it also siphons off some of the finite dining audience and weakens restaurants.

“There’s a lot of ethnic food in LA, very affordable, very accessible, very close to you,” said Jullapat. “Tacos on a street corner are great, but is that pulling us away from smart chefs who are working really hard, shopping ingredients that are grown sustainably and are delicious? We’re competing with that informal economy. We love co-existing, I go eat there when I have a minute, but they drain away dollars from places that pay wages and rent.”

“Grocery stores have materially upped their game in the last 10 to 12 years. If I can go into Whole Foods or an upscale retailer and get a rotisserie chicken as good as any fast-casual establishment, I’m going to do that.”

“I haven’t met one chef who ever complains about this economy, where people can make food cheaper than you,” she said. “We embrace ethnic food and street food and trucks, we like it, it’s colorful, it’s something about who we are as a city. But it does affect us.”

Union Square Hospitality Group’s Chip Wade has two sons in their 20s, so he’s seen the brave new world of mobile meals firsthand. “Convenience stores have blurred the line,” he said. “At breakfast and lunch you can get a wonderfully made sandwich or salad or soup that suits the lifestyle many consumers need and want, with speed and convenience. Grocery stores have materially upped their game in the last 10 to 12 years. If I can go into Whole Foods or an upscale retailer and get a rotisserie chicken as good as any fast-casual establishment, I’m going to do that.”

“And there’s wider choice and variety. If I want to splurge from a dietary point of view and get a high-calorie item, or I want kale with tofu and garlic, I can get both,” he said.

To prove the point, he mentions Wawa, a suburban Philadelphia-based chain of gas stations and convenience stores that’s been around since the 1970s but has experienced what he calls “explosive growth” in the last five years as it marches south along the eastern seaboard toward Florida. Wade ate Wawa sandwiches when he was his sons’ age; he’s impressed that the menu has expanded to include dozens of sandwich combinations, as well as salads and soups, and aware that decent food while you gas up fills a niche for younger eaters on the move.

“They value time and convenience differently than I do or boomers do,” he said.

That brings us to what Wade calls “the 800-pound gorilla in the room,” Amazon, which has its eye on food as yet another retail frontier to conquer. “With their strong financial backing and the acquisition of Whole Foods two years ago,” he said, “they make it increasingly hard for small restaurateurs to stay engaged and operating.”

And Amazon Go, a partly-automated convenience store with two dozen outlets so far, turns grab-and-go into scan-and-go, replacing the check-out line with technology that tracks purchases and extracts payment as a customer shops.

Amazon Go has expanded our notion of what a grocery or convenience store can offer.

An exasperated Michael Cimarusti struggles to understand the appeal of some of the alternatives. He went to an outdoor food festival with his wife and found it “completely devoid of charm, a bunch of people standing on hot pavement, a phone in one hand, lobster in the other, it’s just for the ‘gram,” he said, referring to Instagram. “Is this where we are now, is this okay? It’s so not for us.”

But he was equally bewildered by a restaurant meal where food came out as it was ready, not in courses, even though everyone at his table had ordered their own meal. To him the lack of pacing meant “you don’t know how to coordinate your kitchen. Your server should read the table, or ask questions: ‘Are you going to share or eat what you ordered?’”

“Nobody wanted to eat until everyone had their food, so we were all filled with anxiety,” he said. “Two of us have food and two of us don’t, this meal is going off the rails.” He’s fine eating cheap—a particular New England fish shack is one of his favorite places—but he wants a measure of what he calls “integrity,” both in the set-up and the food.

Restaurants have always been a gamble, thanks to a trifecta of trouble that predates the latest obstacles: Rent, food costs, and labor, known as fixed costs because you can’t have a restaurant without paying them.

The segment that’s the most unstable, mid-range restaurants, suffers in part because its success relies on a business that’s in worse shape than restaurants—retail stores, particularly the ones in vast shopping malls. Online shopping surpassed on-site shopping for the first time in February 2019, and malls struggle to stay alive, sometimes by turning a large anchor space into a food hall. Traffic’s down no matter what. Now that we shop at our laptops we want a meal we can eat at the same time.

“I think the changing retail shopping world may be a factor in restaurant closures, first and foremost,” said Wade. “In casual dining and fast-casual, people used restaurants in conjunction with something else: ‘Let’s go to the mall, and then we’ll leave at 12:30 and have lunch at Red Lobster.’”

In 2014, Darden Restaurants sold the then-struggling Red Lobster chain to Golden Gate Capital for $2.1 billion. Other familiar names across the country land on year-end lists of places that have closed the most outlets: Steak n’ Shake, Boston Market, Ruby Tuesday, Applebee’s, TGIFridays. It’s harder to find a Marie Callender pie in a Marie Callender restaurant than it used to be.

Darden has managed to “buck the trend,” said Wade, with an emphasis on “the value equation, innovation and great execution”—and, it seems, by keeping an eye on the ball. President and CEO Gene Lee declined an interview request through the company’s senior communications director, who said that Lee rarely grants interviews. He prefers to focus on the business.

Leases come up for renewal, and when they do, landlords tend to want more. If the increase is too much for a restaurant they either move or close. Pictured: Huckleberry’s front-of-house operation.

Joe Dietsch

Restaurants have always been a gamble, thanks to a trifecta of trouble that predates the latest obstacles: Rent, food costs, and labor, known as fixed costs because you can’t have a restaurant without paying them. They should add up to about 75 percent of a restaurant’s projected sales, with 15 percent going to smaller expenses, leaving a profit margin of about 10 percent. If any one of the three goes up, as they inevitably do, a very slim profit margin gets skinnier. If more than one goes up, a profitable place can skid into the red, and that’s in a healthy climate, which today is not. Restaurants are not built to withstand change.

—

Leases come up for renewal, and when they do, landlords tend to want more. If the increase is too much for a restaurant to absorb, there are only two options—move or close. No one’s immune: Union Square Hospitality Group had to find a new home for its iconic Union Square Café, the group’s first restaurant, when a 30-year lease expired and the rent rose from $48,000, about $8 per square foot, to a reported $650,000 per year. The $48,000 was a bargain, a reflection of how undesirable the neighborhood was when the restaurant opened, and a dispassionate onlooker might appreciate that the landlord wanted to be compensated for all the years he’d been locked into too little, but that was beside the point. An increase to more than 15 times the existing rent was more than USHG founder Danny Meyer was prepared to pay, so he moved the café a few blocks east and north.

Not everyone is as flexible. As Na Young Ma told me, her popular, nine-year-old Proof Bakery in Los Angeles’s Atwater Village neighborhood is safe until 2031 because she got an extension on her lease at favorable, pre-gentrification rates. But rent is also the reason she can’t open a second outlet: Although she gets frequent inquiries, the rents are always too high to make sense.

—

Doing the right thing is expensive. Josh Loeb and Zoe Nathan use organic ingredients at all their restaurants, but they can’t raise prices enough to compensate for the higher food costs. They open for business every morning with a slimmer profit margin baked into what they sell.

“It’s not an incremental, but an exponential, difference,” said Loeb. “It’s not a level playing field, what I pay for organic butter and organic avocados.”

Managing food costs are the bedrock of any successful restaurant operation. Raise prices too much, and customers will go elsewhere, even if it means they don’t get the same quality.

Joe Dietsch

This is where customers’ wallets and good intentions collide. One of the most promising developments of the last few years is diners’ growing interest in sourcing and sustainability, in Mother Nature’s health as well as their own, but only as long as it makes fiscal sense. If the Rustic Canyon Family raises its prices too much, said Loeb, some diners will decamp to one of the seemingly endless alternatives cropping up in Santa Monica.

“You can’t increase your prices enough to offset prices, so your profit margins shrink,” he said. “On your $10 cheeseburger, costs of ingredients may go up 50 percent over a period of time. I can charge $12, but if I charge $15, a bunch of people will go someplace that doesn’t make everything by hand, doesn’t use the best ingredients.”

“I will only start a business I can operate myself, maybe with one other person to help, occasionally. No investors.”

It’s a cautious two-step, doing the right thing without losing customers.

Jody Williams sees an unexpected advantage in the food-cost challenge for chefs who take a holistic approach to ingredients. Good business, to her, has always meant less food waste. “You have to pay attention to food costs,” she said, “and the way we were trained, we’re very thrifty. We use everything. We’re not using precise little food that’s really decorative, where you just need that one little part of a fish filet, not the head or tail.”

—

The chefs I talked to support minimum-wage increases, and yet they’re frank about the financial pressure they face. Roxana Jullapat already pays most of her 35 employees more than California’s $14.25 hourly wage, which will increase to $15 this summer.

“It’s not that we don’t want to pay them,” she said. “I’d pay them double, but this is not how the economics of the industry work. And when minimum wage goes up, everybody goes up—my $15-an-hour person, who used to make more than the minimum, will come to me and say, ‘I’m making minimum wage, now, and I think I should make more.’”

Some restaurants end up reducing staff to keep labor costs under control. One employee’s raise is another’s pink slip, as restaurateurs redefine essential and decide they can survive without a pastry chef, or ask one person to double up on salads and pre-made desserts.

Paying employees when they’re sick is another welcome benefit, but it comes with a hidden, unpredictable cost for owners, beyond actual sick-day pay. People don’t call in sick a week ahead of time—it’s a last-minute change that requires a last-minute substitute at the salad or pasta or grill station, behind the bar, or as the host. If the person who fills in has already logged 40 hours, they must be paid overtime—again, appropriate, but that shift just cost the restaurant more than anticipated.

Some restaurants end up reducing staff to keep labor costs under control.

Joe Dietsch

“Thousands goes to sick pay,” said Josh Loeb, who employs about 375 people and is quick to acknowledge how fortunate he is, in the grand scheme of things. With nine businesses, the Rustic Canyon Family is not as big as a national chain, nor does he want it to be, but not as small as when he had a single restaurant, Rustic Canyon. He has ways to weather surprise, up to a point.

“We can survive because we have infrastructure, economies of scale within restaurants,” said Loeb, who occasionally has stopped taking the portion of his salary that comes from a specific restaurant, to improve the bottom line. “But if we were just Rustic Canyon? For the first two years it was break even—and if it was now, I’m not sure we ever would have made it to our second restaurant.”

Labor costs are a new restaurant’s biggest hurdle, he said, in part because the smart owner staffs up for an opening, “initially hiring two people to do the work eventually one person will do, because you need people to train and you have people who won’t work out, and on the 50th day you’re better at what you’re doing.”

“The rise of ‘placeless’ restaurants will challenge and redefine the concept of what a restaurant is.”

Nicole Rucker decided that the best solution, after Fiona, was a dramatic detour, so she became a one-woman show. In December, she opened a month-long pop-up called Fat and Flour, a tiny stall in Los Angeles’s Grand Central Market, where she sold pies, cookies, and an occasional special item like biscuits with butter and homemade jam. It was a downsized relief, thanks to the market’s steady stream of thousands of potential customers every day. Her pies often sold out by mid-afternoon, and she intends to re-open the pop-up soon as a transition to the next step.

Later this year she’ll move into a permanent stall in the market: No restaurant, no full-time employees, just a six-seat counter and baked goods to stay or to go.

“I will only start a business I can operate myself, maybe with one other person to help, occasionally,” she said. “No investors.” Rucker has launched a $61,000 Kickstarter campaign that will net her $55,000 after she pays taxes and fees, “enough to get to the finish line. I have some money in my back pocket if it doesn’t fund, so I can get to the $61,000 goal and access what’s been raised.”

“And if it doesn’t work,” she said, with a dry chuckle, “I’ll go be a therapist.” Mental, not physical.

Nicole Rucker turned this tiny space in Los Angeles’ Grand Central Market into a pop-up after her brick-and-mortar bakery closed. It’s a half-step to being back in business: she launched a $61,000 Kickstarter campaign to underwrite the next step, a permanent market stall.

Joe Dietsch

If you think the last decade has brought a lot of change, let me pull a line from a classic 1950 movie that has nothing to do with food. The heroine of “All About Eve” is a famous middle-aged actress who fears, like some established restaurateurs, that her time has come and gone, but won’t surrender without a fight. “Fasten your seat belts,” she warns, as a cocktail party gets going. “It’s going to be a bumpy ride.”

—

The National Restaurant Association predicts more change, faster. The NRA addresses the coming turbulence in a report called “Restaurant Industry 2030: Actionable Insights for the Future,” which anticipates continued churn: “The only constant as we look toward 2030 will be the speed of change and the hyper-competition the restaurant and foodservice industry will face.”

A “nimble” operator, according to the report, will embrace the octopus model that keeps Roxana Jullapat’s Friends & Family thriving, in which a room with seating is only one tentacle of a successful business. A survivor will learn to incorporate ever more data to ensure that a business is efficient and responsive to customer behavior. And there better be “strong motivation to automate routine back-of-house tasks in restaurant kitchens and bars.”

None of which is a guarantee. “The rise of ‘placeless’ restaurants,” the report notes, referring to every variation on the ghost kitchen model, “will challenge and redefine the concept of what a restaurant is.” Get ready for restaurants without borders.

While the futurists at a firm called Foresight Alliance were careful to refer to what they see as “possible futures,” not probable outcomes, that benign description may be cold comfort to restaurateurs who came out of the preceding decade clinging by their fingernails. Among the highlights of the 47-page report:

The Counter

Some of the news is easier to take—the report anticipates a strong commitment to sustainable food and practices, better ways to deal with allergies and dietary restrictions, and customers who dine at off-hours for that data-driven discount, expanding the number of hours a restaurant is busy. Still, the overall message is one of upheaval, enough so that the NRA felt the need to provide a glass-half-full perspective.

“Disruptors,” said the report, “are opportunities, too.”

And the predictions could be wrong, or the results less dramatic than anticipated. The report admits the possibility of “backlash,” of people rejecting automation in favor of a “‘return to artisanal’ movement—predicated on humans being the center of all parts of the food and beverage process.”

Predictions for the future include restaurants increasing their commitments to sustainable food and practices, and better ways to deal with allergies and dietary restrictions. Left, back-of-house staff at Providence in Los Angeles.

Joe Dietsch

Jullapat says it’s happening already. Her young customers—the core consumers of Tomorrowland—seem to want a place where they feel they belong, where they can escape the assumptions other people make about them. Mix that with their interest in idiosyncratic, hand-made food, and there are days when her front room is full of people eating and talking.

They could be the start of an anti-trend, or they could just be a blip. David Portalatin leans toward blip. “Meals are no longer viewed as isolated occasions,” Portalatin wrote in an NPD blog post, to explain why so many meals come with a side order of multi-tasking. “They’re part of an integrated lifestyle.”

But Josh Loeb has faith in the resistance. “That’s what I’m rooting for,” he said. “For all the technology, people will evolve. There will always be a need to be in a restaurant and say, ‘Hey, look, that person’s in the kitchen rolling pasta.’”

If this were a conversation about a landmark building, futurists would complain about empty nostalgia, while preservationists stressed the importance of protecting our history. Since it’s about endangered restaurants, futurists point out that face-to-face interaction is merely one of myriad ways people connect, and we can and should embrace great food wherever it is, while preservationists talk about the civilizing nature of a meal taken with friends and family, possibly without cellphones, away from the distractions of daily life.

It’s democracy in action. Or it’s the end of the world as we know it. Too soon to tell.