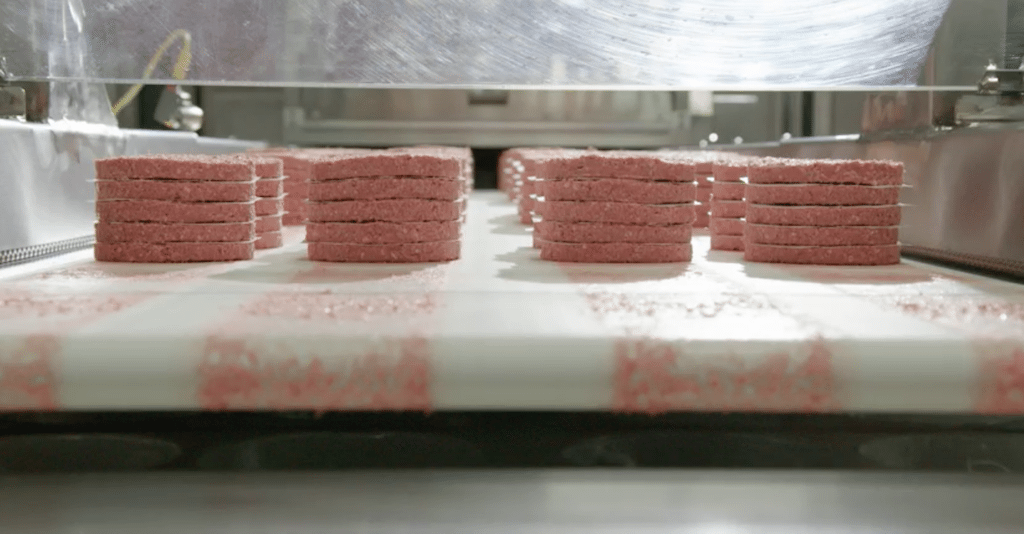

Rahmatallah Gheshm

Dr. Rebecca Brown thought that the sun had set on this year’s saffron harvest. The autumn-blooming plants—which she and her colleague had planted in the University of Rhode Island’s agronomy farm to the northwest of campus—hadn’t produced flowers in days, and winter was imminent.

“We were already a couple of weeks into harvest,” she says. “We thought it was finished.”

Then on Thursday morning, Brown discovered that, unexpectedly, fresh flowers had sprung out from the soil overnight—a sign of just how suitable growing conditions on the Northeast could now be for a lucrative plant that Americans have traditionally imported.

This is the third year that Brown and her colleague, Dr. Rahmatallah Gheshm, have harvested saffron in Rhode Island. Brown is an associate professor of plant sciences, and Gheshm is a postdoctoral fellow in agro-ecology. Their harvests are part of an ongoing research project aimed at assessing how viable commercial farming of the crop could be in the Northeast.

“We’re just trying to answer some very basic questions starting with: Can we grow saffron outdoors in Rhode Island?” Brown says. “[We’re] looking at whether we needed to provide winter protection or not, and what sort of planting density would be best here.”

At the center of every saffron flower are three thin, red threads, called stigma. Once extracted, producers sell these stigma as a valuable and aromatic spice, also called saffron, a coveted ingredient in Middle Eastern, South Asian, and European cooking. Its labor-intensive production and the disproportionate amount of work that goes into producing each strand makes saffron the most expensive spice in the world, commanding up to $10,000 per pound. This means that farmers in the Northeast stand to make a lot of money if commercial saffron harvesting could be incorporated into their production schedule.

Saffron plants in Rhode Island don’t appear to need the protection of hoop houses during the winter, when the leaves sprout in scallion-like grasses.

To conduct their research, the scientists planted 6,000 corms—the bulbous beginnings of every saffron flower—into a field measuring approximately 158 square feet. The land was divided into 16 separate plots, each measuring about 13 by 2.5 feet. To find saffron’s optimal growth conditions, Brown and Gheshm varied density among the plots, protected some with hoop houses during the winter, and left others uncovered year-round.

The idea to grow saffron in Rhode Island came to Gheshm after he was inspired by the Vermont-based saffron research of a friend and former classmate he’d met in their shared home country, Iran. He was curious about how harvest of the spice could be transferred to the particular climate of the Ocean State.

“The milder winters encouraged us to try planting saffron outdoors in Rhode Island, in southern New England,” Gheshm says. In Vermont, researchers needed to transfer their saffron plants into hoop houses during the winter to protect them from the cold.

The study’s results won’t be final until after this season’s harvest is over, but Brown and Gheshm tell me that they’ve already gleaned some preliminary findings. For one, saffron plants in Rhode Island don’t appear to need the protection of hoop houses during the winter, when the leaves sprout in scallion-like grasses. After this year’s harvest, Brown and Gheshm plan to conduct a follow-up experiment, looking at how saffron farming might be able to co-exist—particularly in the summer when saffron plants are dormant—with other crops that local farmers already grow. The project has secured funding from the Department of Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Block Grant Program.

“Could we grow something else like basil or lettuce on that land while the saffron is sleeping underneath?” Brown asks. If so, farmers “could make more money off the space.”

Right now, Iran is the highest saffron-producing country in the world, exporting nearly half of the world’s market, according to UN trade data. However, compared to the sunny, dry conditions in Iran, Rhode Island has a much higher humidity level—the impact of which Brown and Gheshm wanted to observe in their study. So far, however, it appears that the humidity might not be a problem. U.S. is a major saffron buyer, and its demand has never been higher. In 1992, the U.S. imported $3.17 million worth of the spice, a value that has since risen steadily to $16 million last year, according to Census data.

Because of issues like America’s economic sanctions against Iran, Gheshm explains, most of the U.S.’s saffron imports come from through Spain, which is both a major importer and exporter of the spice. Brown believes that local production of saffron can meet the rising demand from American consumers, which she attributes to an increasingly diverse population. What better way to get around a middle man than to grow it in our own backyards?