Last week, Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker announced he plans to move forward with drug-testing requirements for adults applying for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly “food stamps”). This has been an objective of his for a long time—the Republican-controlled Wisconsin state legislature passed a law allowing the change in 2015—but until President Trump took office, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) under Tom Vilsack had made it clear that imposing additional requirements for SNAP access would be blocked by the federal government.

Soon after Walker’s announcement, USDA issued a letter that signaled it will allow states more latitude in deciding how to administer the SNAP program. Though the letter didn’t make explicit reference to Walker’s decision, its timing may indicate the new administration will soon allow states to drug test SNAP recipients.

Drug testing in welfare programs has a long, fraught history. Since the 1990s, states have introduced pieces of legislation that would require recipients of various social programs including Medicaid, SNAP, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF, more on this one later) to submit to drug testing as a prerequisite for benefits. Advocates for testing say it helps identify people who need treatment and prevents abuse in social programs. Critics say it’s invasive and a violation of constitutional rights. District Courts in Florida and Michigan have sided with the critics in the past, ruling that drug testing when there’s no cause for suspicion constitutes unreasonable search and seizure, violating the fourth amendment.

Walker’s rules, if implemented, could prove to be the first in a new wave of state-level policy changes that fall under the “welfare reform” umbrella. Politico reports the White House plans to order a sweeping, top-down review of social programs in the coming months, and Speaker of the House Paul Ryan has said Republicans will target welfare spending in 2018. If USDA follows through on its seemingly permissive (or at least flexible) stance, Politico points out, the move could lead to all sorts of changes in SNAP at the state level, like limiting junk food purchases, changing requirements for eligible stores, and new eligibility requirements.

But what do Walker’s proposed drug tests actually look like? What legal challenges are likely once they’re implemented? And what does it all mean for other states?

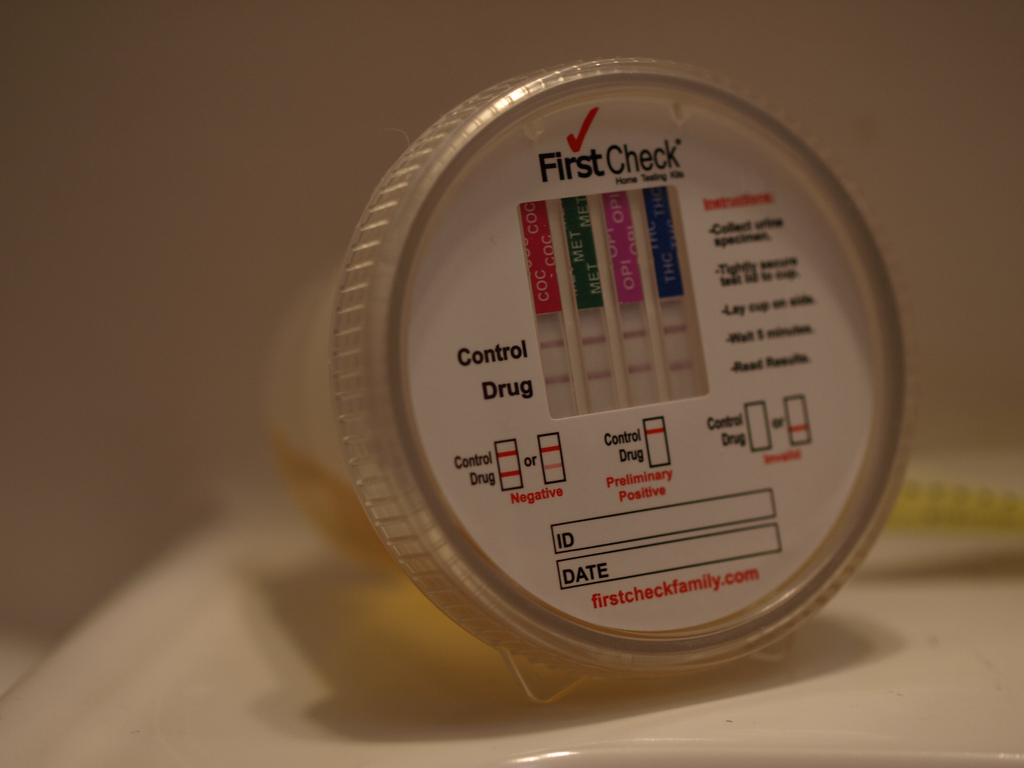

Screenshot of the drug-testing screening Wisconsin may use

Walker’s tests

First, the timeline: The Wisconsin legislature has four months to act on Governor Walker’s missive. Then, the Associated Press reports, it could take up to a year to start drug testing SNAP applicants.

Governor Walker’s in a bit of a tough spot. If he spends too much money on drug testing welfare recipients, he’ll draw criticism from fiscal hawks (this is a man who misquoted Thomas Jefferson on Twitter in 2015, inaccurately stating that the former president once said “The government is best which governs least”). But he’s been beating this drug-testing drum for a while now, so he has to find a way of screening people that’s both cheap and effective.

Enter the one-two punch of the proposed Wisconsin system. According to the state’s Division of Executive Budget and Finance’s Fiscal Impact & Economic Analysis, the drug testing starts with an online questionnaire for applicants. (Quick caveat: Wisconsin’s proposed rules apply only to able-bodied adults without dependents who are participating in the FoodShare Employment and Training program, an outgrowth of federal work requirements for people using public assistance. The program has enrolled a little more than 65,000 people since it launched in April 2015. People who are employed do not enroll.)

The fiscal analysis shows that this automated first step of the process—the questionnaire—will result in in “minimal workload” for the state and local agencies that deal with social programs because it amounts to little more than an online quiz.

I asked Wisconsin’s Department of Health Services what the questionnaire would look like. Spokesperson Elizabeth Goodsitt said in an email that it would likely be based on the DAST-10, or the Drug Abuse Screening Test, which asks participants 10 yes-or-no questions about drug use. Here are a few examples: “Have you used drugs other than those required for medical reasons in the last twelve months?” “Have you engaged in illegal activities in order to obtain drugs?” “Have you neglected your family because of your use of drugs?”

Goodsitt couldn’t tell me how many “yes” answers would lead to a real live pee-in-a-cup-style drug test, the second part of the two-step process, since the department hasn’t confirmed that it will be using the DAST-10 and not a variation on the test.

Still, if the test is online, and participants know that if they say they use drugs they’ll be denied food stamps, what’s preventing people from lying?

The state anticipates that only 3 percent of people who take the online test will score high enough to be subject to an additional drug test. Of those, Goodsitt says about 11 percent are expected to test positive. Those who test positive—an estimated 220 people per year—will be required to seek treatment. An estimated 60 percent of those people will be Medicare enrollees; the remaining 40 percent will be expected to find treatment from county facilities or through private insurance, according to the fiscal analysis. The total price tag for the tests adds up to about $101,500 for Wisconsin taxpayers. The total anticipated treatment costs are about $867,500 and would come from a combination of federal, state, and local funding sources.

It’s all couched as a major money-saver for companies that hire people out of the FoodShare Employment and Training program. “This is a savings to employers who can be confident that people coming through the FSET program will be drug-free, and it’s an opportunity to reduce the economic costs of drug abuse across Wisconsin,” Goodsitt says.

To recap: Wisconsin will screen only the subset of the population that is unemployed and seeking food stamps. Those people will fill out a questionnaire online, presumably knowing that if they indicate they’re using drugs they’ll have to seek treatment if they want to get food stamps. The whole process is likely to cost less than $1 million and render less than 300 positive drug tests. What’s the point of all the fuss?

As Vann R. Newkirk II points out in The Atlantic, the requirements may simply mean fewer people apply for benefits in the first place, a consequence Newkirk suspects Walker is not unaware of. When Wisconsin implemented drug testing for the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program in 2016, ThinkProgress found that more people were denied benefits for failing to follow through with the tests than were denied benefits for actually testing positive. “The chilling effect on enrollment is much greater than the number of people who end up receiving treatment,” Newkirk writes, later adding that Walker’s “insistence on this plan to encourage more ‘people who are drug free’ ignores the fact that there are ways to accomplish the worthwhile goal of treating substance abuse that don’t involve potentially taking away food stamps.”

Electronic Benefit Transfer cards used to distribute SNAP dollars

Potential legal challenges

Assuming Walker’s plan is not blocked by the state legislature or the federal government, it’s likely to face a legal challenge once testing starts in earnest.

In 1999, Michigan passed a law requiring drug testing for applicants for its own Temporary Assistance to Needy Families program. A subsequent legal challenge resulted in a decision by the Sixth Circuit Court, which upheld the District Court’s decision that mandatory drug testing by the state violated fourth amendment rights, rights which protect against unnecessary search and seizure.

Similarly, in 2014, the Eleventh Circuit Court ruled that Florida had failed to show the “substantial need” to test all people applying for welfare benefits after the state passed a law that was challenged in court. That decision was also based on the fourth amendment and unreasonable search and seizure.

Both of the above court challenges apply to the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families Program—I’ll talk about why that program is different from other welfare programs in a minute. But first, there’s one last reason Walker’s plan may not pass muster: There’s a line in the 2014 Farm Bill that explicitly prohibits it.

Here it is: “No State agency shall impose any other standards of eligibility as a condition for participating in the program.” That’s the line Obama’s Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack used to deny state requests to drug test SNAP applicants. It’s worth noting that, in 2015, Governor Walker’s Department of Justice filed a lawsuit suing for its right to test for drugs as it pleases. There’s another farm bill on the horizon—Politico reports House Agriculture Chairman Mike Conaway says it may reach the floor in March of 2018—and it could include changes to federal oversight in SNAP enrollment.

What happened with TANF?

There’s one element of the SNAP/drug-testing playbook that looks familiar.

In the 1990s, a chorus of state governments started requesting waivers from the federal government to allow them to change eligibility requirements for a program called Aid to Families With Dependent Children. “These waivers were mostly designed to allow states to more stringently enforce work requirements for welfare recipients,” wrote Rebecca M. Blank for the National Bureau of Economic Research in 2002. “Such waivers had started under President Ronald Reagan, but the Clinton Administration actively encouraged more expansive state-wide waiver programs.”

Those waivers are exactly what Walker was looking for with his drug tests. But what about that chorus? In 2016, the Associated Press reports, 11 other governors joined Walker in signing a letter in support of—you guessed it—a bill introduced in the House that would allow drug testing for SNAP applicants. That bill, H.R. 4540 or the “SNAP Empowerment and Accountability Act,” didn’t leave committee.

The Aid to Families program got replaced by a block-grant program called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (the aforementioned TANF). A block is a large sum of money granted by the federal government to a local government to spend as it sees fit, with only minimal provisions as to how it is spent.

With states in charge of the dispersal of funds, many moved to implement drug testing requirements.

According to the progressive think tank Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, TANF, since it was launched in 1996, has provided cash assistance to fewer and fewer families, even as need has increased. The average monthly caseload has fallen from 4.4 million families in 1996 to 1.5 million families in 2015, though the number of families living in poverty has increased to 6.5 million.

It’s impossible to know what, if any, impact drug testing has had on TANF enrollment numbers. And block granting the SNAP program seems highly unlikely in the near future, though Politico reports that Democrats and anti-hunger advocates fear Republicans may eventually try.

But the block granting of TANF might give us a glimpse into a future of decentralized drug-testing policy, regardless of whether that future arrives in the form a full-on block grant or simply a relaxation in federal oversight: States that pass mandatory testing laws. Some of them require suspicion of drug use; some don’t. Those laws inch their way through the court system over the course of several years, and ultimately the judiciary decides what rights the constitution does and doesn’t protect. And even if a circuit court or two rules that to test individuals without suspicion is unconstitutional, there’s always a Wisconsin waiting in the wings.