Major new food production and packaging rules were finalized the first week of September, marking a dramatic shift in safety regulations in response to increased instances of dangerous food contamination. The new rules, being enforced by the Food and Drug Administration, are the first wave of regulation changes stemming from 2011’s Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA), which required FDA to revise rules and granted it new powers, including the ability to order mandatory food recalls. The compliance countdown for businesses of nearly every size starts now, with full compliance required for some companies beginning in September 2016.

Meanwhile, the last of these rules — regarding third-party accreditation, produce safety and foreign supplier verification — have been finalized and sent to the Federal Register for publication.

FSMA rules are “probably the most significant legislation since the early 1900s,” says Lauren Handel, a partner at Foscolo & Handel in New York, which calls itself the Food Law Firm. The final rules switch food safety policies from a largely reactionary approach by FDA to a proactive one where food producers are required to have detailed plans documenting preventive safety protocols.

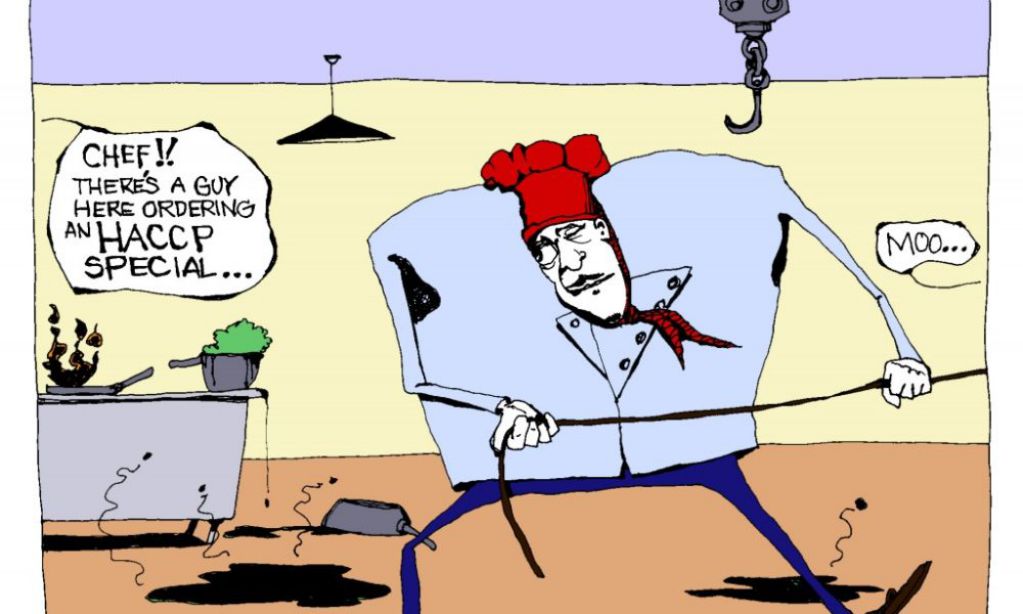

The new rules are more far-reaching than current regulations. One major change: FSMA broadly requires food companies to adopt hazard analysis and risk-based preventive control (HARPC) plans similar to the hazard analysis critical control points (HACCP) systems currently required by FDA that now apply to just seafood and juice. (HACCP systems are voluntary for Grade “A” dairy processors.) Before, a company that produced baked goods, for instance, needed only to comply with basic sanitary regulations. The new rules require a company to develop a detailed plan on its food safety protocols, potential risks, and how it plans to mitigate them, a shift in food policy that moves from reactive enforcement of contamination to one that more specifically aims to prevent it.

The rules require nearly every food company, from local mom and pop operations to the nation’s largest producers, to be fully compliant in less than five years. Size and annual sales determine exactly how long a company has to meet the requirements, which include documenting where it sources its ingredients, how it transports and stores each item, and how it will keep everything free of contamination during production, packing, and distribution. And any change—a new ingredient, an upgraded piece of equipment, or a shift in a recipe itself—will need to be reflected in the preventive documentation.

As for non-farm food business exemptions, Handel says, there isn’t a total exemption, there’s just more time to comply. However, “very small businesses” — defined as those having less than $1 million in annual sales or in the value of food they process or hold — may benefit from a “qualified exemption” (exempt from most but not all requirements). But those businesses will still be required to keep records and submit an attestation to FDA every two years, confirming they’ve either evaluated the hazards of their process and are doing something to prevent them (though not at the level of detail the full rules require), or are complying with state or, in the case of an entity in a foreign company, a foreign jurisdiction’s food safety rules.

“Qualified” is a key word in this exemption because it means FDA can take the exemption away from a very small business if it has reason to believe the business’s facility is linked to a public health risk.

Other exemptions and partial exemptions apply to farms, restaurants and retail food establishments, facilities covered by the produce safety rule or the seafood and juice HACCP rules, and facilities having to comply with the low-acid canned foods rule.

Large food companies are defined as having more than 500 employees. They will have the shortest compliance window—one year after publication. “Very small businesses,” will have three years to comply, and small businesses with fewer than 500 employees that don’t qualify for an exemption will have two years. But full FSMA implementation after the recent finalization of produce safety and foreign supplier verification rules, is likely to take much longer, says Shelly Garg, an associate in the FDA Practice Group of Miami firm Sandler, Travis & Rosenberg.

“It’s a pretty big undertaking by the government and the industry to comply,” Garg says. “It will probably take 10 years for a seamless integration…In terms of how all of these seven rules all fit together, that is something we are waiting to see.”

Handel adds one additional development regarding the supplier verification requirements — or the supply-chain program, as it’s called in the rules, which addresses concern that small companies (with more time to comply) supplying to larger companies (with less time), would have to comply on the faster timeline. Handel says FDA has taken care of that concern by giving recipient companies six months to comply with those requirements after their supplier’s compliance date. But, she adds, “Practically, I’m still not sure how it’s going to play out. Because even if FDA has given larger companies more time with respect to their smaller suppliers, those companies may just decide it’s administratively more simple to treat all of their suppliers the same way, therefore requiring them to comply faster.”

One issue not addressed by FDA’s supply chain fix will be of particular interest to businesses using larger co-pack manufacturers. “They’re going to still have to comply on their own timelines,” says Handel. “Technically, it’s their own obligation under the rules. But as a business matter, they push those costs to their customers.”

But it’s unclear how exactly these entities will ultimately fit into the final equation. “What we are waiting for as regulatory counsel is waiting to see how all of these rules will pair up together and how they will complement each other,” Garg says. “Different entities in the food supply—how will they all interact? How will they all synthesize?”

A major challenge, says Handel, is that there just aren’t enough people in positions to design and implement new safety plans. Though FDA provides online safety training, she says courses like those rarely provide enough information for companies to develop adequate plans.

“I have yet to meet a small company that has a qualified food safety person on staff, and the rules require the plan be developed by someone ‘qualified,’” Handel says. “There’s going to be a huge need for these people.”