I think I owe Hilal Elver an apology.

You may recognize Ms. Elver’s name. She’s the United Nations special rapporteur on the right to food, whose remarks were the subject of an AP story, “UN Expert: Junk Food Is a Human Rights Concern,” that was picked up in dozens of outlets last week.

I read the piece and concluded that Ms. Elver was a nincompoop. Doesn’t she get that there’s a lot more to nutrition than banning junk food? I asked. Doesn’t she realize that this so-called right needs to coordinate with other human rights in ways that are not at all obvious? Doesn’t she care that nutrition is interwoven with other issues like development, investment, and trade in ways that make it treacherous to act too quickly or aggressively?

Then I watched her sparsely attended press conference and read her report to the UN (which was surprisingly hard to locate, given how widely circulated the story was).

Verdict: Not a nincompoop. Not unaware of complexity. In fact, Elver’s report, though it leaves plenty of room for disagreement and refinement, turns out to be one of the most useful guides I’ve found to just how complex nutrition can be and how deeply interconnected with other urgent issues. Her premise is that if we’re going to talk about a basic human right to food, we can’t think just in terms of providing enough calories to fend off starvation. We need to think about providing real nutrition. And treating nutrition as a right gets us into unmapped territory.

It’s not an argument I can do justice to in a few words. But here are some examples of things I think Elver gets right:

The challenge: “Malnutrition, in all its forms, has become a universal challenge. Today, nearly 800 million people remain chronically undernourished, more than 2 billion suffer from micronutrient deficiencies, and another 600 million are obese. These three forms of malnutrition coexist within most countries, communities and even individuals. Ensuring the right to adequate food extends far beyond merely ensuring the minimum requirements needed for survival and includes access to food that is nutritionally adequate. Increasingly, the right to adequate nutrition is being recognized as an essential element of the right to food and the right to health.”

Children: “WHO has concluded that malnutrition is the underlying contributing factor in about 45 per cent of all child deaths. . . . In 2014, there were 159 million stunted and 50 million wasted children in the world, and by 2030, stunting is expected to affect 129 million children. At the same time, there were 41 million overweight children under the age of 5. If this trend continues, 70 million infants and young children will be overweight or obese by 2025.”

The double whammy: Poverty and inequality are drivers of obesity and micronutrient deficiency, in addition to undernutrition. Low-income populations are particularly vulnerable to obesity. Processed foods tend to be highly accessible and relatively cheap and can be stored for long periods without spoiling. . . . Unable to afford healthier food options, individuals may become overreliant on poor-quality foods, essentially being forced to choose between economic viability and nutrition and exposed to ‘double malnutrition.’”

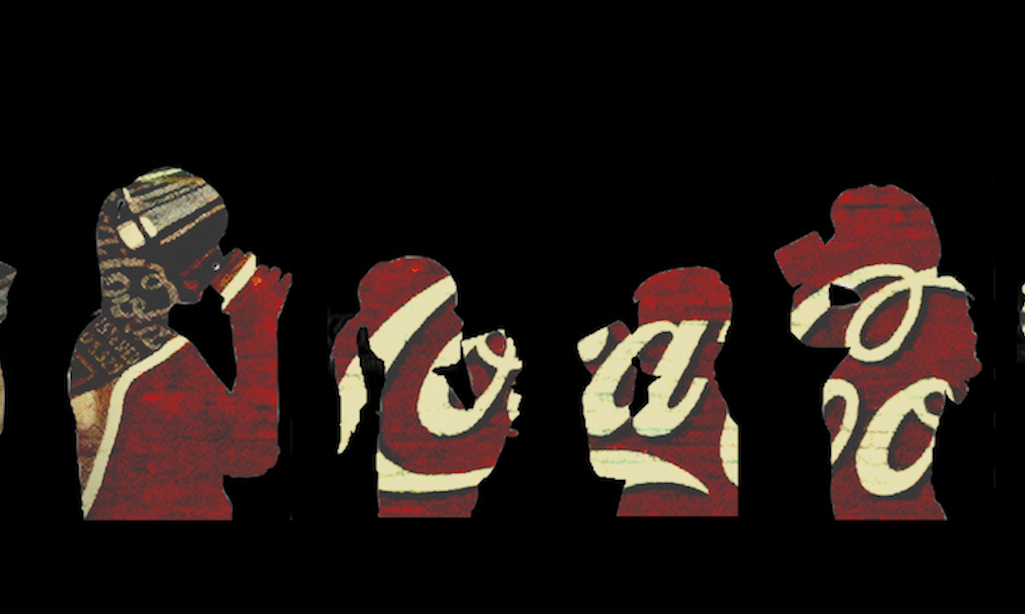

Foreign direct investment: “FDI is playing a significant role in the “nutrition transition”. The food processing industry is now the largest recipient of FDI, particularly in support of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods. FDI allows companies to become transnational by purchasing or investing in ‘foreign affiliates’ located in other countries, which then produce food for the domestic markets. This allows the foreign-based company to bypass import tariffs and lowers transportation and production costs. By flooding markets with cheap refined grains, corn sweeteners and vegetable oil, FDI has become a driving force behind rising obesity rates in developing countries.”

Nutrition and development: “The [U.N. Sustainable Development] Goals have a universal character and cannot be achieved without special attention to nutrition. While Goal 2 explicitly refers to ‘nutrition’ and Goal 3 to non-communicable diseases, nutrition is arguably interwoven within all 17 Goals.”

Corporations: “While recognizing that companies play a big role in fighting malnutrition, there is a danger in giving corporations unprecedented access to policymaking processes, which may produce conflicts of interest at several levels unless governed properly. It has been questioned whether nutrition policies can deliver both short term financial returns for companies and long-term social and health benefits that help to effectively tackle global malnutrition challenges. Adequate safeguards are thus needed to ensure that the private sector does not use its position as a ‘stakeholder’ to influence public policymaking spaces on nutrition to promote commercial objectives.”

There’s much more where that came from, and it’s worth your attention. That’s not to say that you’ll agree with everything. If you’re a hard-core believer in the power of markets, you’ll probably find the approach too top-down for your taste. You’ll probably wonder, as I do, why there is so little on farmers or on the role of global changes in employment, urbanization, and life style. Some of the proposals, such as taxes on non-nutritious food, will be much more complex to implement (especially within already-damaged food systems) than they appear on the surface. And some proposals—such as the idea of exempting food taxes and other market restrictions from World Trade Organization rules if they are justified in terms of nutrition—sound almost impossible in real-world terms.