Talia Moore

Twitter’s impact on public health has been under the microscope in recent years, as research suggests the social media platform may cause information overload, fuel anxiety, and enable harassers. But what about Twitter’s ability to provide meaningful data on public health outcomes at the community level? Researchers are now using it as a tool to explore correlations between the way various communities talk about food on social media and their overall health outcomes.

Since 2016, Dr. Vinod Vydiswaran, a professor at the University of Michigan, has been working on a project aimed at understanding how food-related discussion on Twitter could be useful in reducing differences between health outcomes in various communities. Initiatives focused on changing our behaviors around food and nutrition require meaningful, timely, and—most important, local—information to be effective. So, Vydiswaran wanted to know whether Twitter could be a valid source for neighborhood-level data points about our dietary choices and attitudes.

But divining meaningful public health data from the global swamp of 280-character tweets is not as simple as typing “bacon” into the search bar and analyzing the results, of course.

Along with several interdisciplinary Ph.D. students, Vydiswaran began by cross-referencing tweet content with location data. They identified roughly 153,000 people who had tweeted about food in the Detroit, Michigan, area, then stripped out influencers and people who didn’t seem to live there. They were left with a set of 800,000 food-related tweets from more than 62,000 people.

From there, they built a machine learning-based model to help determine whether tweets that included words like “honey,” for example, were actually relevant to their research: “Honey, don’t get me started” is not the same as “Controversial opinion: I hate honey.”

From the keywords that remained, connections could be established between mentions of unhealthier foods like “bacon” and “fries,” and the relative affluence of the community.

Those connections yielded a finding the researchers called “intriguing”: Higher-income neighborhoods—defined in this study as the proportion of people making more than $75,000 a year—tended to tweet less positively about food, whether healthy or unhealthy.

Tweets from lower-income neighborhoods—those where a higher proportion of people made less than $75,000 a year—tended to show something different. “A lot of people like to talk about food and have strong opinions about food,” Vydiswaran says. This led to a new hypothesis to explore, that “food may be an isolated source of enjoyment in otherwise difficult lives.”

The researchers also made a curious discovery: Neighborhoods with more young people were less likely to tweet positively about unhealthy foods. This seemingly counterintuitive finding could auger well for future research.

The complete findings, published in the Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association last month, also includes an examination of the correlation between food-related tweeting and mortality rates from obesity-related causes of death. The Twitter-based “food healthiness measure” showed a modest but statistically significant correlation between neighborhoods that tweeted more about unhealthy foods and higher rates of heart failure. There was a less significant but still notable correlation between tweets and kidney failure.

The researchers were building on past research that shows, for instance, significant connections between the caloric value of foods people tweet about and state-level obesity rates. This is the first research that aggregates and analyzes that information on a micro, neighborhood level. Additionally, previous social media-based research has lacked dietary specifics such as sodium intake, fiber, and added sugar.

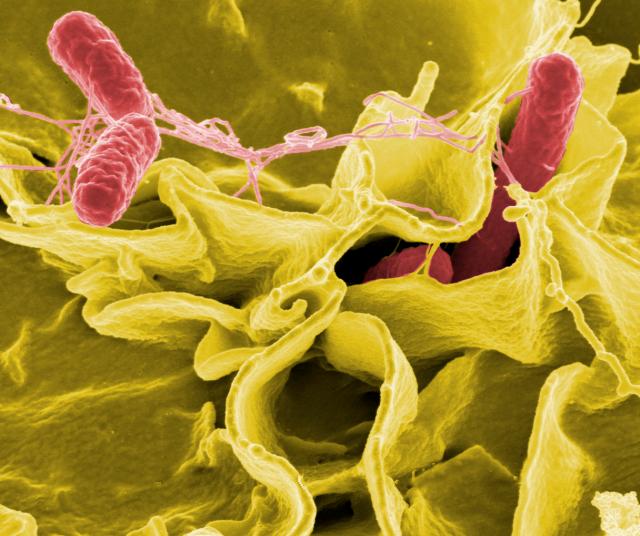

Vydiswaran says this research shows promise for policymakers interested in improving community health outcomes. Urban planners, for instance, might analyze tweets to identify neighborhoods that would benefit from being more walkable. Vydiswaran says data for that kind of research is generally gleaned from surveys, which are expensive and time-consuming. Twitter, on the other hand, is real-time information from a global community of users. Elsewhere, researchers are hoping Twitter might also be used as a tool to investigate foodborne illnesses.

The University of Michigan researchers have future plans to analyze Twitter data to gain insight into local exercise habits and alcohol consumption. They plan to cross-reference neighborhood liquor license density with Twitter mentions of terms like “hangover” and “wasted.” “What we want to really study is binge drinking and heavy drinking,” Vydiswaran says, adding that the data may be particularly interesting because of the high concentration of college students in Detroit and its surrounding areas.

City councils may never base their sidewalk construction priorities on nebulous Twitter sentiment. But for now, we’ll be thinking twice the next time we want to tweet about smashing a whole pizza in between lunch and dinner. You never know who’s reading.