USDA just opened up America’s largest temperate rainforest, “the lungs of North America,” to logging. Resistance is coming from unlikely places.

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) yesterday announced a final decision in exempting Alaska’s Tongass National Forest from the so-called Roadless Rule, clearing the way for logging and road construction in the world’s largest intact temperate rainforest. The decision, which comes nearly two years after Alaska petitioned the federal government for the exemption, was praised by Governor Mike Dunleavy and Senator Lisa Murkowski, both Republicans, who said it would bring more jobs and money to the state.

But conservationists say that clear-cutting the pristine rainforest would destroy animal habitat, as well as threaten the state’s fishing, tourism, and recreation industries—which they say are now far more important to the state’s economy than logging. They say the fight to protect the forest—which began decades before Alaska’s petition—is not over, and threaten litigation.

“There’s every reason to be outraged,” said Lance Preston, a salmon troller in Sitka, Alaska. “A very small minority is going to make a lot of money, and the majority are going to be hurt.”

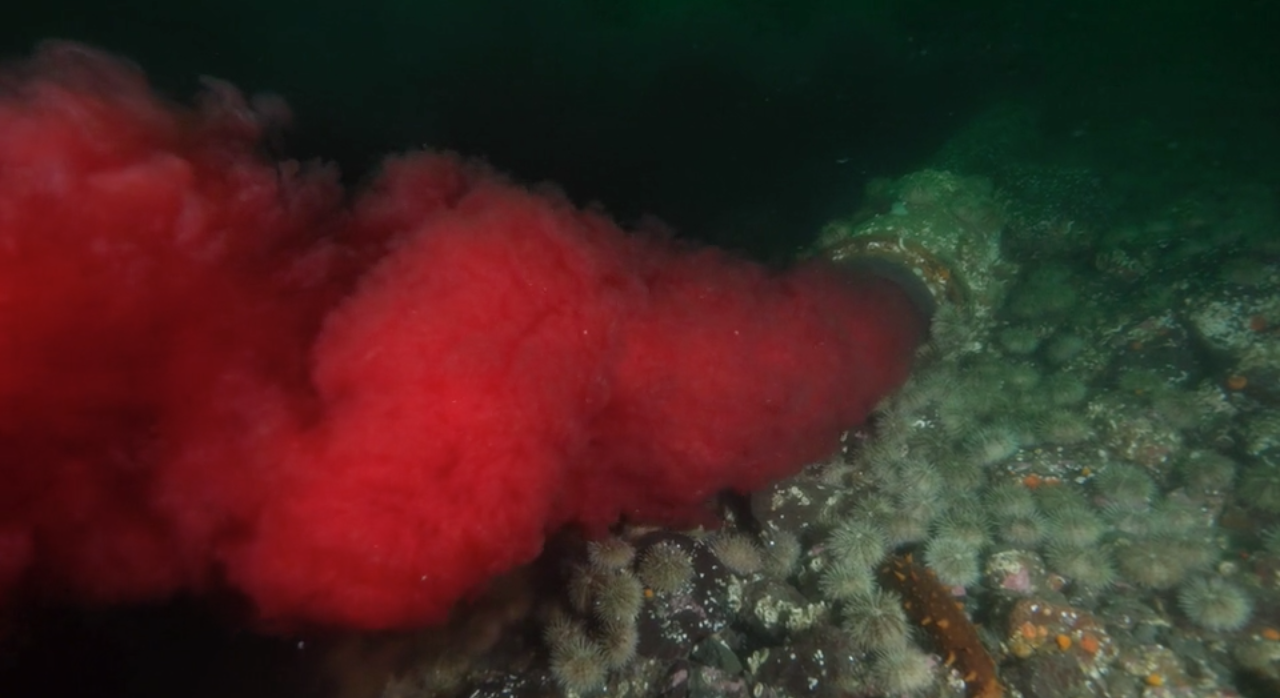

The 17-million-acre Tongass is America’s biggest national forest. Sprawling across southeast Alaska, the landscape boasts high populations of bears, wolves, and bald eagles. Rivers run wild with salmon and trout, and tourists flock to miles of sandy shoreline and misty fjords. The old-growth trees absorb at least 8 percent of all carbon stored in American national forests, with one scientist calling them “the lungs of North America.”

The Tongass also has a long history of logging, with its old-growth spruce trees feeding Alaska’s timber industry from the 1950s to 1990s. After decades in decline, President Bill Clinton banned road building and timber harvesting in 9 million Tongass acres in 2001, as part of a nationwide action called the Roadless Rule. But Alaska’s leaders have long argued the Roadless Rule should not apply to their state, and in 2018, after Governor Bill Walker petitioned the Forest Service for an exception, USDA announced its intention to roll it back.

Environmentalists and fishers say that’s far from the truth, and that industrial logging represents a threat to another Alaskan tradition: salmon fishing.

“A very small minority is going to make a lot of money, and the majority are going to be hurt.”

The exemption does not authorize any specific logging projects, which must still comply with a management plan and are subject to federal review. Murkowski and other state politicians say it will unlock valuable resources, and help “build a more sustainable economy.”

The Tongass is a salmon powerhouse, producing around 50 million salmon annually, or around 28 percent of the state’s total catch. It generates around $986 million in annual value for commercial, sport and subsistence salmon fishers, according to a Forest Service report. Fishing and tourism in southeast Alaska account for 26 percent of regional employment, according to the Southeast Conference business group.

“This is a politically driven decision, and it’s not responsive to the public,” said Austin Williams, the Alaska director for law and policy for Trout Unlimited, a conservation group that opposes the rule change. In a December letter submitted to the Forest Service, one of more than 15,000 sent in opposition to the carve-out, Williams wrote that the most valuable activities on the Tongass are not logging, but those “derived from intact fish and wildlife habitat and wild scenery.”

“This is a politically driven decision, and it’s not responsive to the public.”

He says logging poses threats to the salmon runs that are the backbone of all that activity. When trees are cut down, forests lose the shade that keeps the water cool, and protects salmon eggs from the hot sun. Without roots, soils are more prone to erosion, and sediment dumps into streams. Clear-cutting makes for less large, woody debris that falls into streams and creates natural habitat for spawning and rearing.

[Subscribe to our 2x-weekly newsletter and never miss a story.]

Road building, in particular, is a major threat to salmon habitat, both by overburdening streams with sediment from construction, and by cutting off their runs. Thousands of miles of logging roads already cross Tongass streams and rivers, making it harder for salmon to head upstream to spawn and rear, and for ocean-bound fish to travel downstream. Culverts underneath these roads are supposed to allow for passage, but they can cause blockages, high-velocity currents, and scour streams.

Williams added that one third of all bridges and culverts already in the rainforest don’t meet salmon migration standards, and dozens of watersheds need significant environmental remediation. He wrote that damage to once-thriving salmon runs, in places like the Harris River, or the colorfully named Fubar Creek, begs “the question of why we would compound these problems through expanded road construction in new areas.”

“I want to do everything I can, because this is our legacy. The Tongass is the closest thing we have to the Amazon.”

In its environmental impact statement, the Forest Service found that the Tongass excemption would have minimal or negligible effects on fish habitat, according to The Cordova Times. Overall, USDA said, it would not have “major adverse impacts” to fishing, recreation, or tourism industries, the Associated Press reported.

But Preston, the salmon troller, disagrees. He says clear-cut logging is brute and imprecise, like “mowing the lawn,” and that the 100-foot buffers required “don’t do nearly enough” to stop erosion or diminish temperature effects. Last year, he says, was his worst coho salmon catch in over 30 years. And with fewer trees in the forest, he expects it to get worse. Studies show Alaskan salmon species are shrinking, which means they lay fewer eggs, make smaller catches, and represent fewer dollars for fishers like him. Warming waters are partly to blame.

“This is putting me more in a mind of seeking alternatives to fishing,” he says. “I want to do everything I can, because this is our legacy. The Tongass is the closest thing we have to the Amazon.”

An official notice of the Tongass rule change is scheduled to publish in the Federal Register today.