Steph Chambers/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette via AP

The “Rust Belt Diner” genre of journalism isn’t new. But it has changed since 2016—underscoring the hardening of symbolic lines between an mythic “Real America” and the rest of the nation.

Here’s a story: A Presidential candidate makes a campaign stop at the Chat and Chew, a diner in a Rust Belt town that’s long been a Democratic stronghold but has started to trend more Republican. The New York Times is there, covering the candidate’s conversations with former employees of the Western Electric plant, which is located across the street. The prospect of economic hardship haunts these interactions: “While there are still about 2,000 workers at the plant,” the Times will later report, “it is being phased out and eventually will be closed.” The workers are receptive to the Presidential candidate’s message. They like him. He’s a Washington outsider, an iconoclast aiming to shake things up.

If you’ve followed political journalism at all in the last few years, this story probably feels familiar. It has all the hallmarks of the so-called “Trump Country Diner” genre: Journalism that takes reporters to a hardscrabble setting—often a small town built around a closing plant, abandoned mine, or boarded-up Main Street—to learn more about the opinions of its white, working-class, politically conservative residents. Local diners are a fixture of such stories, and not only because they’re a good place for reporters to find sources. They also play a heavily symbolic role, functioning as the stage media outlets use to suggest some kind of fundamental Americanness—despite the fact that these Republican-leaning districts provide only a narrow window into the nation’s soul.

Diners play a heavily symbolic role, functioning as the stage media outlets use to suggest some kind of fundamental Americanness—despite the fact that these Republican-leaning districts provide only a narrow window into the nation’s soul.

One of the most recent Trump Country Diner pieces ran just last week, on Great Britain’s Sky News, which reported from the Summit Diner in Somerset, Pennsylvania; every patron quoted supported President Trump. The story’s subhead: “Coal and steel industry towns opted for Donald Trump in 2016, and for many there’s no sign their support is dwindling.” Fox & Friends also recently resumed its regular diner reporting after a pandemic-related pause, kicking off the latest round with interviews that included one woman who told reporter Pete Hegseth, “the virus is over. We need to step away from the fear.” There were no dissenting voices.

Over the past four years, the relentless barrage of similar-sounding dispatches has spawned a Twitter meme, one referenced by both Beltway insiders and their followers. Often, it’s a sarcastic commentary on a particular article—in response to a New York Times story on the views of non-Americans on the current state of the USA, The New Yorker’s Isaac Chotiner quipped, “Foreigners, In Break With Pennsylvania Diner-Goers, Don’t See Trump As Successful Businessman.” Other times, it’s a standalone piece of joking punditry, like this 2018 tweet from reporter Daniel Dale, who was at the time the Toronto Star’s Washington bureau chief:

The genre has even inspired full-blown parodies by, among others, Washington Post satirist Alexandra Petri, Politico’s Adam Wren, and two different writers for McSweeney’s. “Craig is a contradiction, but he does not know it,” Petri wrote. “Each morning he arrives at the Blue Plate Diner and tries to make sense of it all. The regulars are already there. Lydia Borkle lives in an old shoe in the tiny town of Tempe Work Only, Ariz., where the factory has just rusted away into a pile of gears and dust.” The headline on one McSweeney’s piece? “I Traveled to a Diner In Trump Country to Write Another Article On Whether the President’s Supporters Still Want to, Quote, ‘Smash My Libtard Face In.’”

[Subscribe to our 2x-weekly newsletter and never miss a story.]

But all of this warrants closer consideration. Why are Trump Country diners—and the white, working-class patrons who frequent them—so heavily overrepresented in our political journalism? And what does that obsession tell us about the way elections and their consequences are dramatized in the press?

While it’s easy to mock the clichéd nature of Trump Country Diner stories, it’s worth examining their origins and their deeper meaning, because as it turns out, the genre’s roots stretch back long before the guy from “The Apprentice” ran for office. The Presidential candidate who made that campaign stop at the Chat and Chew outside the Western Electric Plant in Tonawanda, New York, in that seemingly archetypal Trump Country Diner story? That was Jimmy Carter. The article appeared in The New York Times back in 1976.

Like diners themselves, the tropes at play here turn out to be American classics.

—

I’m a longtime diner obsessive. I love the communities and stories they embody and the way they provide a 24/7 hangout for all kinds of people in all kinds of neighborhoods. I’ve had a Google Alert for “diner” for since 2005, with updates filling my email inbox every week. And as I’ve watched the Trump Country Diner stories play out through both actual journalism and social-media jesting over the last few years, I’ve wondered where they came from, exactly—what cultural evolution led to this symbolism at this moment.

I started to pore over old newspaper articles (primarily through ProQuest and the New York Times archives, as well as other sources) to look for any political stories with a diner setting. There were plenty to choose from, all from the last fifty years or so (nothing before the 1970s). It was immediately striking that, in many ways, the details have stayed exactly the same, but the precise symbolic meaning of diners has changed, as has the particular format of the stories.

Democratic running mates Gov. Bill Clinton, left, and Sen. Al Gore make a post-rally stop at Doe’s Cafe in Corsicana, Texas, on Friday, Aug. 28, 1992.

AP Photo/Stephan Savoia

Looking at all these articles, it’s clear that there have been three distinct eras of diner journalism. During the first period, from the 1970s through the 1990s, these articles nearly always centered on the candidates themselves—like Jimmy Carter in Tonawanda—making campaign-trail stops. In the New York Times, for example, this included a 1985 story on New Jersey gubernatorial candidate Peter Shapiro, a Democrat, greeting supporters at a Hackensack diner; a 1987 story on Senator Gary Hart, a noted diner fan, working the blue-collar crowd on the presidential campaign trail at a New Hampshire diner; and, in 1993, a piece on New Jersey Republican gubernatorial candidate Cary Edwards campaigning at a diner in the town of Wayne (“The yuppie wants cheese on his onion rings,” one of his aides teased).

All of this is telling in its own way. Candidates love diners for the same reason they love Ben’s Chili Bowl or flipping pork chops at the Iowa State Fair: They’re a photographable connection to everyday folks. Emily Contois, an Assistant Professor of Media Studies at the University of Tulsa, explained it to me this way: Most politicians are “far afield from the average American family” in terms of power and economic status, and yet “there’s this idea that if they eat $4.99 pancakes next to you, then you can feel this authenticity and this sense of realness with them.”

It’s why we’re so obsessed with what flavor of milkshake candidates prefer, or how they eat their pizza: It’s a marker of how well they function as “ordinary” people.

During the first period, from the 1970s through the 1990s, these articles nearly always centered on the candidates themselves—like Jimmy Carter in Tonawanda—making campaign-trail stops.

But more recent diner-based journalism has a different driving force: Instead of a venue where candidates become more real, it’s become the place where reporters go to search for realness.

It wasn’t until the mid-2000s that we started to see a large number of diner stories without candidates present in the flesh. It’s difficult to pinpoint a precise cause or year that journalists started to poll diner patrons—though it’s worth noting that diners saw increased business and cultural resonance as symbols of nostalgic Americana after September 11th. But one piece in the Washington Post in 2004 stands out as a clear early example of an emerging genre. Over lunch at an unnamed but “classic” diner in Elyria, Ohio, a politically disaffected crew of men held court, including conservatives who weren’t sure if they would vote for George W. Bush, lamenting that “the Republicans have gone from manufacturing to finance.” Then again, they didn’t really care for John Kerry. What to do? In this telling, finally, the customers—not the politicians—became the stars of the narrative.

Note, though, the way this was framed, and what the patrons represented: A Nation Divided, a focus group of swing voters. In this type of story, which grew increasingly common throughout the 2000s and the early 2010s, there was an emphasis on lively disagreement grounded in civility and camaraderie and an idea that a diner is truly neutral territory, where arguments never fester and the bacon never runs out.

“The town is probably the most ethnically diverse in the county and as one moved from table to table, political diversity was evident as well,” the Daily Record in Morristown, New Jersey reported in another characteristic piece, shortly before 2008 election. Four years later, the New York Times went to a diner in Elyria, Ohio (as the Post had previously) and observed that “the presidential election sometimes serves as a conversation starter, like a curio placed between the salt and pepper shakers.”

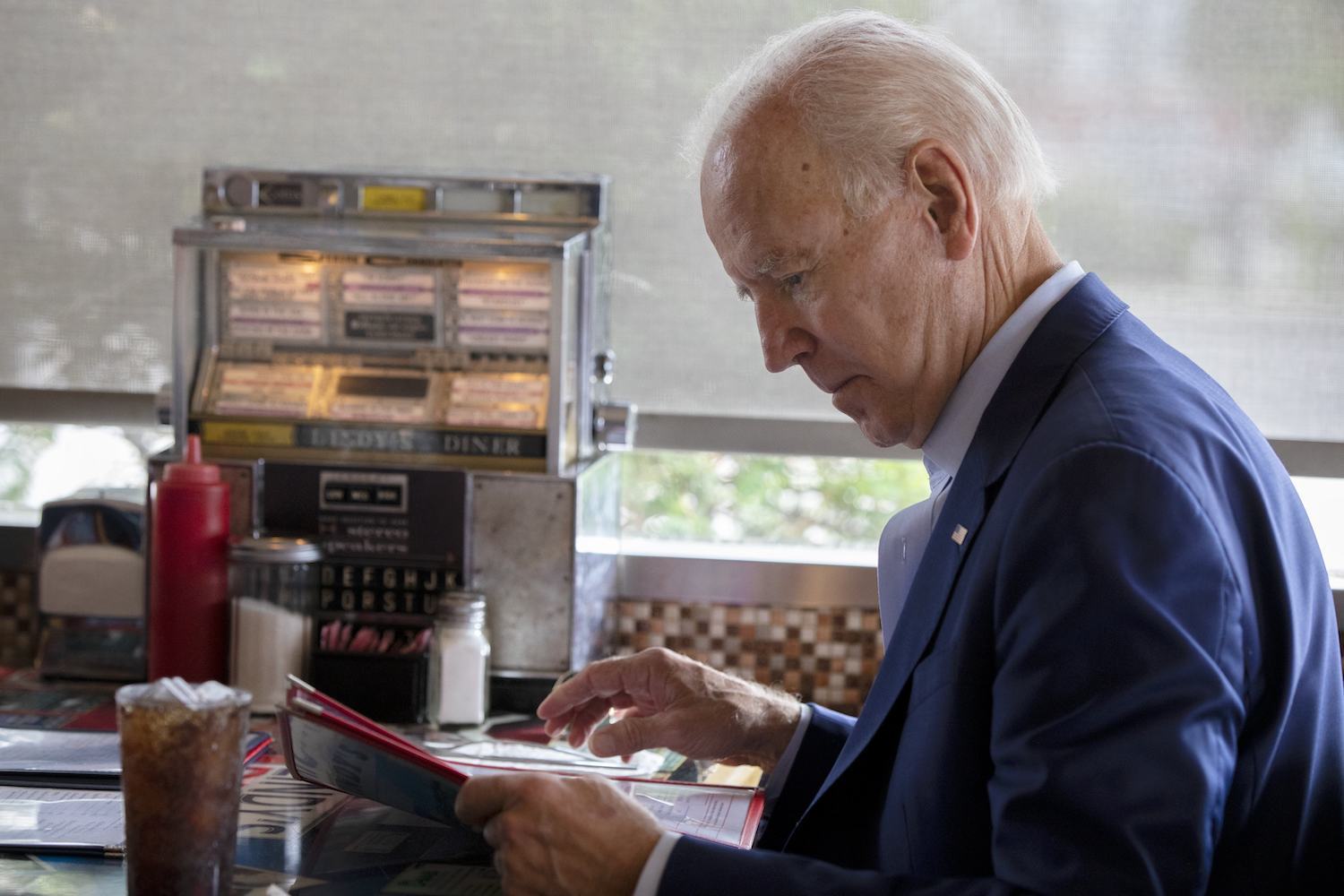

Former Vice President Joe Biden consults a menu during a presidential campaign stop at Lindy’s Diner in Keene N.H., Saturday, Aug. 24, 2019.

AP Photo/Michael Dwyer

What’s interesting about these pieces is that they lacked the decidedly partisan lean of today’s Trump Country Diner stories. In these earlier versions, the diner was a site of lively banter but, ultimately, American harmony—a place where divergent perspectives could compete for elbow room at the coffee counter. Those tensions seemed to reach new heights in the lead-up to the 2016 presidential election, as the first news stories connecting Donald Trump, politics, and diners tended to focus on his critics. A Washington, D.C. diner owner added a bologna-filled Trump Sandwich to his menu in August 2015, garnering coverage in The New York Post and Fox News. In January 2016, ABC News reported a customer at the Red Arrow Diner in New Hampshire heckling the candidate—“Enjoy your burger, racist!” Still, the diner-patrons-as-focus-group style of news coverage also continued, and the existing template held strong. Here’s the opening of a piece from the Christian Science Monitor in March 2016:

It’s a cold and gray Friday at the Pioneer Restaurant, and the Utica Coffee Club is in session.

Every weekday morning – for so long no one can remember – a group of friends has been meeting in the back of the Pioneer here in rural Utica, Ohio, a town described by one member of the group as having one doctor, no dentist, and a Ben Franklin store that is closing.

Around the table, there’s a veterinarian, a farmer with 450 cows, a guy selling cheese and raffle tickets, and even a former member of the Clinton administration.

They’re mostly retired and in their 70s, but perhaps their most remarkable characteristic is their ability to talk about any political topic—from Hillary Clinton’s e-mails to Donald Trump’s immigration plans—and still be willing to buy breakfast for the rest of the table on their birthday.

—The Christian Science Monitor, March 15, 2016

Again, the long-established formula: an All-American yet melancholy setting (Ben Franklin is closing!), a range of patrons, lively discourse. You can find it all, too, in an August 2016 Mother Jones story featuring union leaders meeting at the Yankee Kitchen outside Youngstown, Ohio (a city of “skeletal remains of steel mills”), their conversation focusing on their lukewarm support for Hillary Clinton and the rifts in their broader ranks.

In these earlier versions, the diner was a site of lively banter but, ultimately, American harmony—a place where divergent perspectives could compete for elbow room at the coffee counter.

In fact, prior to the 2016 general election, the closest thing to the clichéd Trump Country Diner story, with its tables full of MAGA loyalists, appears to be—no joke—a BBC dispatch from an American-style diner in Moscow, complete with an ad-hoc infographic made with ketchup and mustard bottles.

—

For journalists, heading to diners has a few levels of appeal, beyond a hungry scribe’s own desire for food. As Washington Post political reporter David Weigel put in his essay “Consider the Diner,” the typical patron “has a little bit of time on his hands and is probably in a decent mood,” what with the food and the coffee. He or she is also likely to be a low- or medium-information voter, as opposed to the news enthusiasts you’re likely to find at a campaign rally. Beyond all this, Weigel told me in a phone interview, for some reporters there’s “kind of a veneration of this as a space where people [have] homespun unique wisdom.” It’s the same dynamic that Emily Contois highlighted regarding political candidates: a sense of authenticity by association.

Joe Fassler

Former Presidential candidate Rick Perry makes a 2012 campaign stop at the Hamburg Inn No. 2 diner in Iowa City, Iowa.

Weigel was quick to note that this approach is limited. For one thing, he says, “you’re already announcing your participation in an economic strata if you can afford to eat out at all.” At the same time, patrons aren’t necessarily an ideal cross-section of the USA—or even their own geographic community. It’s also clear, digging through the news archives from the mid-2000s up to the 2016 election, that the narrative of diner stories always focused on a specific type of customer: the white, working-class residents of small towns, that narrow slice of Americana that has long been venerated as the Heartland, the Real America. This skewed definition—which ignores people of color, immigrants, residents of large cities, and others—is common across American society, but it’s useful to see it at work even in an ostensibly egalitarian setting whose very draw is comfort food. There’s always symbolism, and it’s usually telling a familiar tale.

This goes along with a construct Contois discussed in a recent article in the journal American Studies—and in her forthcoming book, Diners, Dudes & Diets—about Guy Fieri’s nostalgic, populist version of small-town identity: “this imagined Main Street community excludes members along the lines of race, class, gender, and sexuality.”

Such restricted claims and coded appeals were, of course, instrumental to Donald Trump’s entire campaign in 2016. And the change in diner journalism after his electoral victory underscores the hardening of the symbolic lines between Trump’s version of “the Real America” and the rest of the nation.

—

In November 2016, immediately following the election, diner-driven political journalism reached new heights—or new lows, depending on your point of view—propelled by a sense, even a certainty, that the national media had failed to understand the collective mood of the vast interior of the U.S. Therefore, the thinking went, reporters needed to spend more time getting to know these places: The Main Streets, the Heartland, the Real America.

This symbolism handily tied into the presentation of Trump as a “blue-collar billionaire” whose key areas of success came in the Rust Belt areas where diners are especially plentiful.

The day after the election, The Los Angeles Times juxtaposed an unnamed Hillary Clinton supporter at a “posh Miami café,” with a detailed description of the scene at a family restaurant in Stanley, North Carolina—a “rail town of 3,600”—where a plumber named Terry Brown said, “I don’t know anyone who would vote for Hillary Clinton.” Another patron added, “she should be locked up.”

Less than two weeks later, The New York Times was interviewing Trump supporters in a central New Hampshire diner—despite the fact that Hillary Clinton actually carried the state, if only by about 3,000 votes. By the end of November, even smaller publications had gotten on the greasy-spoon bandwagon, including The Wisconsin State Journal, which opened a story with quotes from the Trump-supporting owner of a rural diner, and the Pacific Northwest nonprofit newsroom Crosscut, which ventured to the small town of Ritzville, Washington, calling it “something of a time capsule from the 1950s. Even the names of the throwback storefronts hint at this — Memories Diner, the Ritzville Pastime Bar and Grill.”

The trend only grew in December. An Associated Press dispatch from Sandy Hook, Kentucky, for instance, began with this sentence: “The regulars amble in before dawn and claim their usual table, the one next to an old box television playing the news on mute.” That lead, and the accompanying story, soon caught the eye of The Week columnist Ryan Cooper, who reported on the phenomenon in a December 28, 2016 piece titled, “The media is blinded by its obsession with rural white Trump voters.”

Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Rodham Clinton greets customers during a campaign stop at the Union Diner, Thursday, Sept. 17, 2015, in Laconia, N.H.

AP Photo/Jim Cole

“For some reason, they always open in a diner,” Cooper observed. Less than two months after the election, the template was already so established as to be a cliché.

From the outset, many of the Trump Country stories were jarringly anthropological, with more than a tinge of hackneyed travel writing, featuring the same narrative and the same cherrypicked locals, each inscrutable, exotic, and, in some fundamental way, wise. If Paris is chic flâneurs wearing berets and sipping espresso in the Latin Quarter, the towns of Middle America were all out-of-work machinists wearing feed-store hats and slurping from chipped mugs of Folgers on dying Main Streets. The diner setting was not incidental. Like the cafés in a fluff piece about the good life in Paris, the diners of Trump Country were an essential cultural marker, a nod to an outsider’s preconceived sense authenticity and, in this case, a direct link to the intertwined populism, nationalism, and nostalgia of Trump’s Make America Great Again appeal.

This symbolism, Contois notes, also handily tied into the presentation of Trump as a “blue-collar billionaire” whose key areas of success came in the Rust Belt areas where diners are especially plentiful. Political storytelling is dependent on symbols (Soccer Moms! Morning in America!), and if the usual conservative trope of rugged individualism didn’t quite work for a guy who no one has ever called “rugged,” well, diners seemed to fit.

After Trump took office, reporters continued to stalk red-state diners, to the increasing chagrin of some news connoisseurs. As far as I can tell, the Twitter meme began to take off with a joking tweet by David Weigel, on February 15, 2017, commenting on Michael Flynn’s resignation as national security advisor: “What we need now is a dispatch from Ironburg, Ohio, where 80% of voters picked Trump and now sit around in a diner defending Flynn,” which he followed with another tongue-in-cheek Rust Belt Diner tweet two days later, and many, many more since then. (Weigel has likely tweeted the meme more than any other prominent Twitter user. He’s done his own share of diner-based reporting in his career, he told me, but the sheer predictability and lack of genuine insight in most of these post-election stories made them easy sport for social media and “started to turn this into parody.”)

By late April 2017, two weeks after the Washington Post’s Alexandra Petri satirized Trump Country Diners, the real-deal versions reached their peak in a Christian Science Monitor article featuring a ten-day road trip through Ohio, Kentucky, and West Virginia to ask “diner owners and customers for their thoughts on President Trump’s first 100 days.” The premise was right there in the headline: “Fried pickles and populism: a diner tour of Trump Country.”

AP Photo/Alex Brandon

Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Barack Obama leaves a campaign stop at Schoop’s diner in Portage, Indiana, on Wednesday, Aug. 6, 2008.

The stories were built on the same concept as the earlier form of diner journalism: a quest to understand the Average American. But now, though the basic reportorial format still applied, the particulars had shifted. Diners were still a quintessential part of the culture, but they were no longer places of lively debate—instead, they were defined by conservative consensus, a place where Trump supporters of varied backgrounds hung out to praise the president and malign his opponents. In the rare instances that a liberal does appear, it can be a jarring sight—as when, in 2019, Fox & Friends reporter Todd Piro encountered a young, hyper-articulate Green New Deal supporter at a diner in Missouri, an awkward moment that became Twitter fodder for U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Piro’s surprise and incredulity was evident in his voice, his body language, and his multiple requests for the man to repeat what he’s saying, “just to be clear.”

For a while, there were so many Trump Country Diner stories that the same people and places showed up in multiple versions: reporter Salena Zito, who built a reputation for her Trump Country reportage, featured customer Ed Harry at D’s Diner in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania in separate articles for the Associated Press, the New York Post, and the Daily Beast, and Zurich newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung also interviewed him as their representative voice of Trump-supporting Americans.

Some repetitions were instructive, revealing how the narrative of diner reporting had changed. While Mother Jones’s pre-election reporting from the Yankee Kitchen in Youngstown, Ohio focused on the divisions within the local community, by May 2019, the New York Times used the same spot to show that “blue-collar workers are sticking with Trump.” The Times set the scene by saying, “A good place to sample what’s on people’s minds is the Yankee Kitchen, where the tables and long curving counter were packed for breakfast on Saturday.” It was presented as a casual, unplanned drop-in, with a guidebook’s air of detachment, never mind the earlier visit by Mother Jones or the fact that Vanity Fair had stopped into the very same eatery in 2018.

“All these profiles of Youngstown and I have yet to see one which notes that more than half the population of the city is black or Latino.”

There were fundamental flaws, though, in all of these stories. A central problem was the way these outlets focused on white working-class conservatives at the expense of other demographics, creating an artificial sense of monolithic whiteness. As New York Times columnist Jamelle Bouie observed, “All these profiles of Youngstown and I have yet to see one which notes that more than half the population of the city is black or Latino.” There’s also the not-so-small matter that Hillary Clinton defeated Donald Trump in Youngstown. And then there’s the fact that the Yankee Kitchen is perhaps not the best stand-in for the city, given that it’s actually several miles north, in Vienna Township. Never mind all that: There’s a story to tell, a particular trope to work with. That’s the allure, the point, and the problem.

—

The Trump Country Diner story, as actual journalism, seems to have peaked sometime in 2017, briefly trailing off in the early months of 2020, when the coronavirus pandemic changed in-person dining and campaigning as we know it. It’s also plausible that, beyond the coronavirus, these stories have faded because it’s harder to portray Donald Trump as the “blue-collar billionaire” when he’s running against Joe Biden, whose whole thing is “the man from Scranton.”In the early days of the Democratic primary season, Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez called Biden “the perfect candidate … to win that guy in the diner.” (It wasn’t a compliment; it was a criticism of the narrowness of his appeal to voters.)

You can still find Trump Country Diner stories here and there, of course, including the aforementioned Sky News piece from Pennsylvania and the recurring “Breakfast with Friends” segments on Fox. The meme is still strong on Twitter, too. But for the most part, when diners have appeared in political journalism, it’s typically been in the earlier style, as places of robust debate. When the Washington Examiner went to a small town in Michigan in September, the takeaway was that “Biden voters are the shy ones” and that the local diner was “a microcosm of the divided community.” Yet even this reversion to a less-skewed symbolism merits questioning, since it still distorts reality. Because diners are so ubiquitous, you can find them virtually anywhere. Because they’re such potent cultural icons, any one of them can be viewed as fundamentally, quintessentially American. These simultaneous facts mean you can find a diner that represents any specific viewpoint, and extrapolate—either by accident or design—to present it as the pulse of the nation.

A banner for Trump/Pence US election ticket seen during a Steve Bannon Speaking Engagement on Zoom with Queens Village Republican Club in Triple Crown Diner, Middle Village, Queens.

(Photo by John Nacion / SOPA Images/Sipa USA)(Sipa via AP Images)

This is what happened with the Trump Country Diner stories and why they were so maddening. They were a sleight-of-hand trick of cultural symbolism: Diners are quintessentially American, therefore the patrons in this particular diner are quintessential Americans. And yet, even before the rise of the formulaic Trump-era articles, and even after they began to wane, that trick has always been performed in one particular way, always reinforcing the same racist notion of a “Real America.” You could find a diner that’s also a Meals on Wheels center, or one that’s a Michelin-starred bistro. You could find a working-class halal diner or a Midwest kosher diner or a red-state vegan diner or a diner in literally thousands of big-city neighborhoods rather than another small town. You could use diners to showcase virtually every ethnic group, cultural identity, or political perspective in the United States. You could use diners to showcase immigrant success stories and the benefits (and deliciousness) of cultural pluralism. But that would mean telling a more nuanced, more complicated story—a longer route, to be sure, but one much more likely to arrive somewhere closer to the truth.

“What we also need are ‘diner pieces’ that focus on the other, far less covered group that could genuinely alter the outcome this year,” Financial Times writer Neil Munshi wrote in his own essay on Trump Country Diners in September. “Reporters covering 2020 should be thinking about how around 20,000 black or brown votes in Milwaukee, 10,000 in Detroit and 40,000 in Philadelphia would have flipped 2016.”

“What we also need are ‘diner pieces’ that focus on the other, far less covered group that could genuinely alter the outcome this year.”

A savvy politician or attentive reporter could seek out these voters in all kinds of places, including their own local diners, and use them a tale of the USA beyond the usual tropes, the America of reality rather than “the Real America.” And I’ll keep searching for those stories, in hopes that they’ll start to materialize.

Given the history, though, I’m not optimistic. I suspect, instead, that diners will continue to be used to showcase a particular cohort of white, rural, working-class citizens. They’ll continue to be coded—contrary to all available evidence when you look at where diners are and what they represent—as nothing more than a relic of an imagined 1950s now dying out, a paradise lost along with all those factories crumbling in the background. Those bad-travel-writing narratives, with their gritty yet subtly romantic details, are apparently too hard for many reporters to resist.

America prides itself on adaptation and reinvention. Yet the diners of political journalism remain static, a portrayal that says a lot less about the restaurants themselves than it does about how rigid and regressive that misleading narrative can be.