Portrait: Mike Prince | Collage: Alice Heyeh for The Counter/iStock

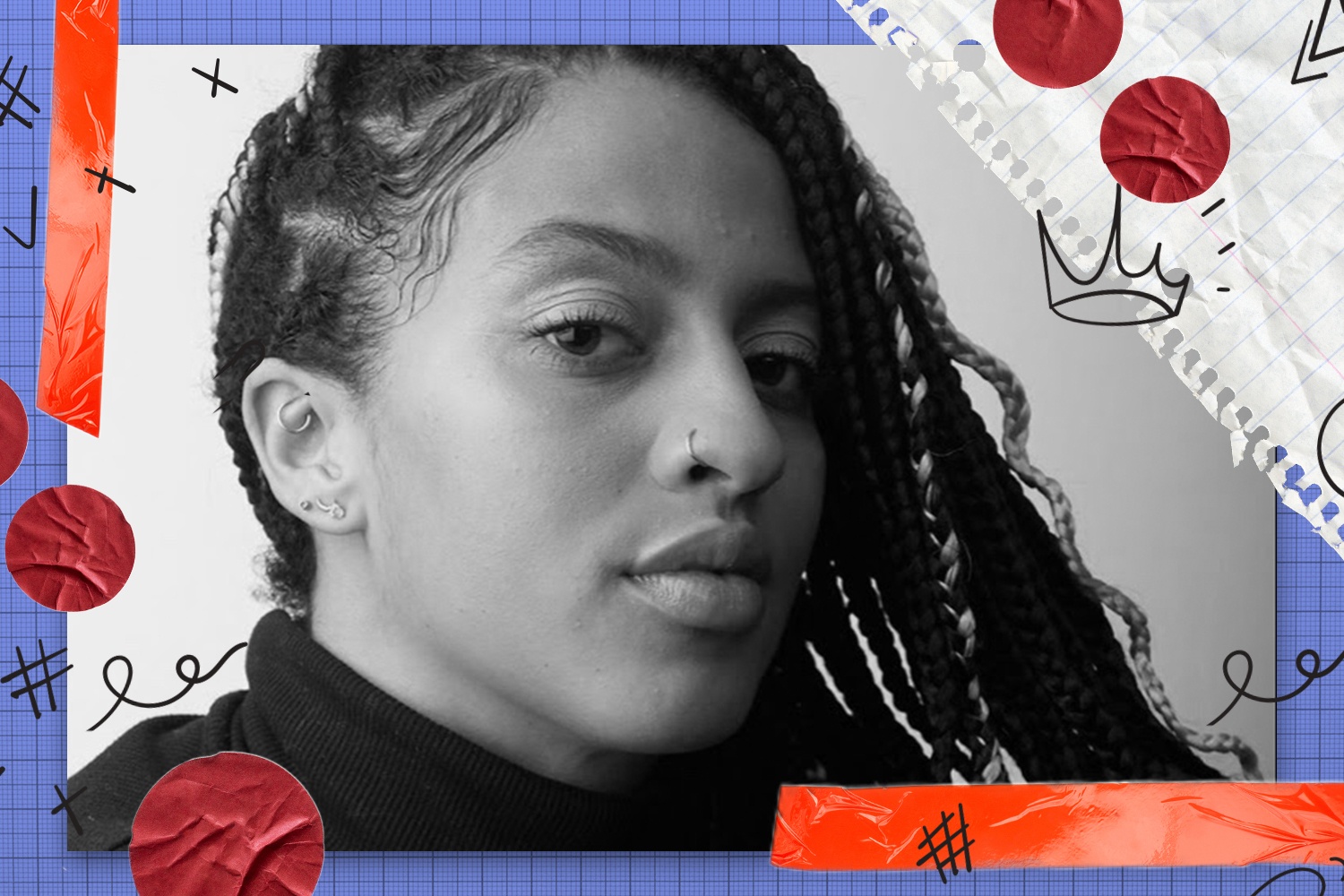

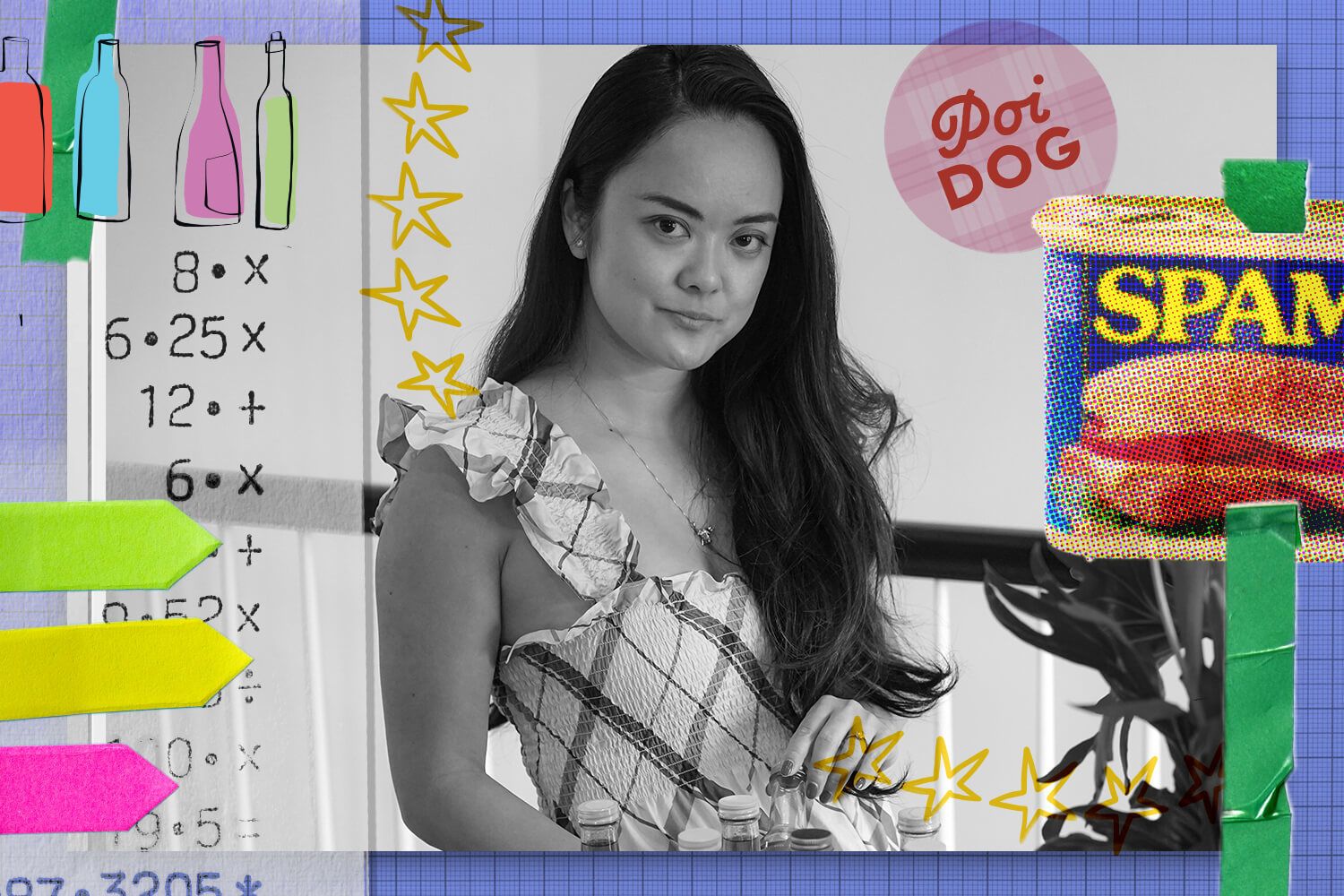

Kiki Aranita’s beloved restaurant, Poi Dog, celebrated Hawaii’s complex food culture. She’s keeping the spirit alive, one fiery bottle at a time.

Kiki Aranita and her former business partner Chris Vacca spent years building and perfecting every aspect of Poi Dog, a Philadelphia restaurant that celebrated the diversity and complex flavors of Hawaiian food culture. When the pandemic forced them to close shop last summer, Aranita, a culinary dynamo who is also a food writer, teacher and in-demand recipe developer, met the moment head-on with a new business idea: Starting her own line of hot sauces.

—

I was in grad school for a very long time, in two different PhD programs, which makes me sound very smart and fancy. But the reality is I quit two PhD programs. The most recent one was at Bryn Mawr College out in the suburbs of Philadelphia. My specific research interests were in classical, epic and Renaissance Italian poetry. I still very much care about the topic. But I was sort of at the end of my rope when it comes to academia. And so in 2013 I bought a food truck.

I’ve always been really interested in food, growing up in two very rich food cultures in Hawaii and Hong Kong. My dad’s family is in Hawaii. We spent several years there. When I was 12, we moved to Hong Kong. Summers and winters, we were back in Hawaii. We basically split the year between both. That’s the background of Poi Dog, which means mixed breed or mutt, which is what I am, and which is what our menu essentially represented. It was sort of a gathering place for people with Hawaii connections, but also people who had visited Hawaii and fell in love with the islands. It was the only way to share Hawaii’s culture and food with Philly, this new adopted city of mine. A lot of people called us a Hawaiian restaurant, which we weren’t really. We were a restaurant that served Hawaii’s local food.

Kiki Aranita opened Poi Dog in a four by eight foot food truck in Philadelphia. Their signature dish was mochi nori fried chicken with furikake in the batter and togarashi-yuzu mayo.

Courtesy of Kiki Aranita

I had a partner at the time who was for a long time my boyfriend. We were really scrappy for the first four years. We had the smallest food truck on Earth—four by eight feet on the outside. The menu grew item by item, starting with chicken guava katsu. We started getting booked for festivals where there were thousands of people. Chicken katsu takes a really long time to fry. We thought, “We have to come up with something that is fried chicken, because people love fried chicken. But we can’t have these really long lines.” We started making mochiko chicken, which are much smaller pieces of chicken breaded in rice flour.

I’ve always been of the philosophy that constraints give way to creativity. In this case our constraints were: We’ve got a lot of people to feed, and we have to come up with something unique and delicious, but it still needs to reference Hawaii roots. Our signature dish—mochi nori fried chicken with furikake in the batter and togarashi-yuzu mayo—grew out of that.

We started getting booked for weddings and corporate events. Apparently it’s a thing to have a luau in the summer here in Philly. So I accidentally fell into this niche area that hadn’t been filled by any other food business. There were no other businesses that focused on Hawaii’s food.

No matter how we did the numbers, we always came up short. We could not survive without having weddings and corporate events and classes at UPenn in session.

After four and a half years, we found the perfect restaurant space. The place was in Center City and it was close to a lot of our main clients. Our biggest client at this point was UPenn. We were one of their preferred vendors. We were also close to the Comcast buildings. There were a lot of office workers, a lot of law offices, but then Philadelphia shut down for indoor dining. It was March 17 or 18. We switched for the first few days to takeout and delivery, but we felt the effect right away. The delivery platforms at that time were charging 30 percent of each of our orders. We weren’t making any money because 30 percent of our money was going to these platforms. We decided to temporarily shut down and didn’t open again until the very end of May. We started only doing once a week take-out and pick-ups. We were very much affected by foot traffic, or lack thereof.

Then we did the math. No matter how we did the numbers, we always came up short. We could not survive without having weddings and corporate events and classes at UPenn in session. We needed all of that in order to have a sustainable, break-even business. Here’s the most boring advice of all time: base your decisions on numbers, not on hopes and dreams.

Aranita found a restaurant space after operating Poi Dog out of a food truck for four and a half years. Most of their customers came from UPenn and surrounding office buildings.

Courtesy of Kiki Aranita

We only had a year and a half remaining on our lease, so it wasn’t too hard to get out of it. We gave away most of our restaurant equipment to up and coming businesses that do the world good. I’m actually still working on some closing paperwork. Closing a restaurant requires a ton of paperwork.

Do I miss running a restaurant? I miss running a restaurant before the pandemic. Do I want to be running a restaurant right now, with widespread staff shortages, lack of people eating out, and without guaranteed corporate catering budgets? I miss it from before, but I’m glad I’m not doing it right now.

The sauces came purely by accident. I was cooking at an event at Poconos Organics in September of 2020, and one of the things I made for this event was the chili peppah water. My friends at Burlap & Barrel were also at the event and they said I should bottle it. They told me how one goes about starting a retail business. And then I started one.

I’m still learning the ropes. I’m very lucky to have unintentionally made sauces that are high in vinegar, which makes them much more shelf stable.

The Lavender Ponzu is entirely my creation. I think a lot of people are familiar with how ponzu tastes, but they don’t necessarily know how it tastes with a floral component like lavender. That was just me tinkering around in the kitchen. The chili peppah water is very well-established in Hawaii. The guava katsu—I mentioned that was one of the first things we served in the food truck. The version I made in the food truck contained chicken stock and Worcestershire sauce. The version that I make now, which tastes exactly the same, is vegan.

I’m still at the very beginning of it. I’m still trying to figure out what all the acronyms mean. There’s a lot of jargon; there’s so much to learn. The first place I went to was the Drexel University food lab. I was like, ‘How do you make sure the stuff is shelf stable?’ I needed a primer on food science and they gave me one. They also sent me to Rutgers. I worked a little bit with a food scientist there, tweaking formulas, learning about acidified and non-acidified foods.

I work with two different co-packers now. I’m still learning the ropes. I’m very lucky to have unintentionally made sauces that are high in vinegar, which makes them much more shelf stable. If I was coming out with a frozen product, well, God help me.