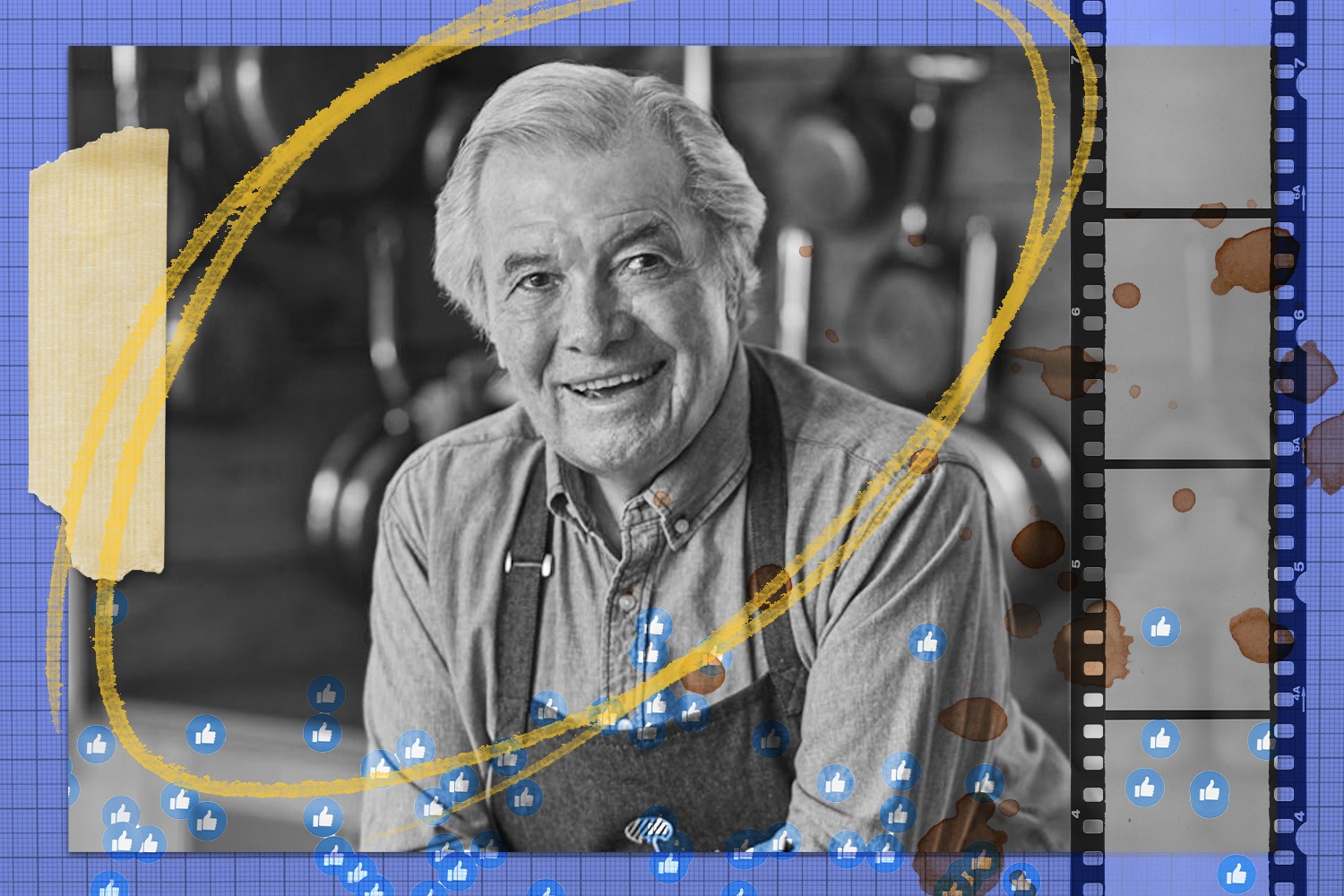

Portrait: Courtesy of Irene Li, Collage: The Counter, iStock

Boston’s Irene Li turned a restaurant into a dumpling company—then turned away from it to help small-business owners.

Irene Li co-founded the Boston restaurant Mei Mei with her two siblings in 2012. Since then, she’s been nominated for the James Beard Foundation’s Rising Star Chef of the Year award six times. Just before the pandemic shuttered her restaurant, Li broke down Mei Mei’s finances for the world to see: In a year that brought in $1.2 million in income, the restaurant netted just $22,000 after expenses. Now, the owners have reimagined Mei Mei and Li is helping other restaurant owners get a handle on their finances through a program run by CommonWealth Kitchen, a nonprofit shared kitchen facility.

—

On March 9, 2020, we had just hosted a public event where we used this funny little technology called Zoom and presented our profit and loss statement to the public. The moral of the story was basically that restaurants are more complicated and less profitable than anyone thinks.

I’m pretty sure I said the sentence, “A lot of businesses only have a couple of months of operating expenses in the bank.” And then the pandemic hit, and that became really clear to everyone.

We closed Mei Mei on March 16, before there were any orders from the governor of Massachusetts. I could just hear my dad telling me, ‘Don’t trust the governor to keep you safe. Listen to what the doctors are saying. You’re better safe than sorry.’

Read the transcript for Irene Li’s audio quote here.

I have always judged myself as a leader and a person based on how I can take care of the people who are close to me, including my staff. Trying to find any small thing to do for my people was the only thing that kept me together. We bought toilet paper and eggs and pasta in bulk. We launched an internal grocery program which we extended to other industry workers and anyone who had any food insecurity issues.

We also moved much of the staff to working remotely on special projects and administrative projects, on marketing and communications. We started doing a lot of research on retirement plans for staff. For a handful of folks who maybe didn’t have internet access at home or just weren’t interested in doing work on their computer, they would help us with meals for hospital workers. That’s how we were able to keep people employed up through June.

June is when things started to shift, and we had to think longer term about what our plan was going to be. We knew that the added federal unemployment benefit was going to be running out. That’s when I made the decision to do the layoffs that we had put off in March.

I have always judged myself as a leader and a person based on how I can take care of the people who are close to me, including my staff.

To be totally honest, I think that’s probably the most traumatic process I’ve ever been through. I think maybe some of the laid-off staff would say the same thing.

There’s part of me that felt like the constraints of HR, of corporate culture, of capitalism influenced me to go against my gut feeling, which probably would have been to spill the beans to everyone and have a good cry.

Instead, they got a copy/pasted email, ‘Hey, we want to meet at this time.’ We had a number of staff who declined to appear at their layoff meetings. For a few staff members, there was just not really any closure. One thing I heard was that getting a copy/paste email was really insulting.

Mei Mei’s dining room closed in September 2020. Now, Irene and her partners have launched Mei Mei’s own dumpling company.

Courtesy of Irene Li

Everyone can have their own true version of the story and there is enough empathy to go around, and to meet the pain that all of us are feeling over it.

I felt like, oh, my God, I don’t want to employ anyone ever again. I think I called it a seven-layer dip of despair.

The turning point was when we had a regular customer who sent us an email asking if we would want to come sell any of our prepared foods at the farmers’ market. We gave it a shot starting in September.

The farmers’ market honestly felt like a gift from whoever in heaven is running things. People were so happy to have us there, and it was such a controlled environment for safe human interaction. It just felt like magic. We started putting feelers out to join other farmers’ markets. And it snowballed from there. That is when we started thinking about a future that was not as a restaurant and that would be as a packaged foods company.

I think I knew that we were not going to reopen the restaurant for a while before I published a blog post announcing the closure, September 30, titled ‘This is not a restaurant.’ At a certain point, I just looked at the team and I felt like, ‘If anyone dies because I wanted to keep the restaurant open, I will regret that for the rest of my life. I would rather lose my business than think that I had a team members’ blood on my hands.’ The essence of Mei Mei would live on as a packaged dumpling company.

The farmers’ market honestly felt like a gift from whoever in heaven is running things.

I thought that turning Mei Mei into a dumpling company was the right plan, but that didn’t mean I liked it, at least not on a personal level. I really felt—emotionally, practically—like I couldn’t make this change. I needed to bring someone else in to do it. As that happened, I became less and less crucial to like daily operations.

As my schedule was starting to clear up, I was thinking about what kind of impact I wanted to have. There was a voice in my head that was like, ‘Your former employees hate you. Your business is not the same. And everything you’ve been doing for the last eight years has just crumbled.’ That voice was very persistent.

But there was this other voice which said, ‘Nothing that you’ve done is a waste of time. Everything you’ve done has been about learning and making mistakes and improving based on them. And you just have to find the next thing that will turn what feels like a failure into valuable experience.’ I had been engaged with CommonWealth Kitchen, a nonprofit shared commercial kitchen facility, as a board member for about four or five years. And as the Restaurant Resiliency Initiative (RRI) started to take shape out of the CommonWealth Kitchen’s initial emergency funding for restaurants to cook for their neighbors, I just inserted myself in the conversation. And eventually I ended up as the program manager, which is what I’m doing now.

We’re working with eight businesses over 16 weeks. We’re getting in up to our elbows and doing some very hands-on work with them.

All of them are fighting to get to the point where they can work on the business and not in it, meaning they can step back from day-to-day operations and think bigger picture. Your financials can be useful for helping you make those really hard decisions that you’ve been just relying on your gut for. Like, ‘Should I take this dish off the menu? Because I think it’s too expensive, but people really seem to like it.’ Or, ‘I’m not open on Sunday nights, but maybe I should be.’

Being able to relate on that level is a superpower that I’ve discovered in the course of working with these businesses.

Everyone who is in the program has either been part of the CommonWealth Kitchen network or has been supported by a peer organization. Many of them have a handful of tables, but primarily they do takeout. These aren’t businesses that needed to be saved from the pandemic—they’ve actually done okay or even fairly well because they’re smart and they’re scrappy and they got some support. The program is really about setting them up for success at the next level, whatever that means for them. There’s a lot of energy for Black- and Latinx-owned businesses. We want to make sure that they are in a position to take advantage of the opportunities that we feel really confident are going to come their way.

For many of them, the owner is unpaid or minimally paid. One of the business owners still does contract work as an electrical engineer.

Courtesy of Irene Li

Irene with her siblings. They ran the restaurant together for several years before she bought them out.

Rethink Restaurants is a consulting group that supported Mei Mei in the open book management implementation, educating our team on business finance, creating monthly all-team financial meetings, teaching me personally about financials and other best practices. Now I get the pleasure of working with them as the curriculum providers in RRI. So we meet several times weekly with someone from Rethink, the business owners, and the CommonWealth Kitchen Recovery team.

I want these businesses to have the luxury to afford to make moral decisions. Right now, a lot of these businesses pay a sub-living wage. They probably are not able to offer tons of benefits. I want all of them to get to the point where they can pull the trigger on these really important things. I think that’s part of the ripple effect, too, because we see all these problems in the restaurant industry and we can’t fix them with unprofitable businesses.

I have referred to this many times as my dream job, and I don’t think I would have ended up here if not for all of the fallout of the pandemic.

A lot of the people on a lot of the Zoom calls I’m on, they’re all white and they have never owned a restaurant. Even without deep racial politics, it still stands to reason that I am actually suited for this. I ran the business with my brother and sister for many years before I bought them out. That was a really complicated, joyful, sad, everything experience. So many of these small businesses, these BIPOC-owned, immigrant-owned businesses, are also largely family businesses, or friends who went into business together. Being able to relate on that level is a superpower that I’ve discovered in the course of working with these businesses.

I still kind of hold the spiritual identity of Mei Mei. As I’ve continued to get into other kinds of work, I’m always reporting back to the team there. And I’ll pinch hit for a dumpling-folding shift or go to a farmers’ market as needed.

It’s hard to believe this is where I am, but, you know, I wake up in the morning and I’m like, ‘Oh my God, I can’t wait to start my meetings.’