Doug Mills - Pool/Getty Images

The governors parroted talking points pushed by some of their past donors: that $300 per week pandemic payments were encouraging people to turn down work.

Pictured above: Tilman Fertitta, CEO of Landry’s Hospitality, makes remarks during a roundtable with Restaurant Executives and Industry Leaders at the White House on May 18, 2020. Landry has given more than half a million dollars to Texas Governor Greg Abbott.

One month ago, the CEO of Landry’s—a $6.6 billion hospitality company based in Texas that includes in its portfolio multiple restaurant chains, like Morton’s Steakhouse and Bubba Gump Shrimp Company—hopped on cable news to raise alarm over what he believed was a major factor in the restaurant industry’s labor shortage: supplemental unemployment benefits.

Since December 2020, laid-off workers have been able to collect an additional $300 per week on top of their regular unemployment payments, a measure intended to help families make ends meet during the pandemic downturn. (Between March through July 2020, that bonus equaled $600 per week.) But with vaccinations rising, Covid-19 cases falling, and restaurants returning to full capacity after over a year of social distancing restrictions, a CNBC anchor asked Landry’s exec Tilman Fertitta: Could it be that Texans were “riding” on these unemployment benefits to avoid returning to work?

“100 percent,” he responded. “There’s no employees out there.” Fertitta also said that “the extra $300 a week” is emboldening people to turn down job opportunities, for example those at his restaurants offering $14 an hour.

This messaging was later parroted by Republican Texas Governor Greg Abbott, who announced that the state would soon cut these very payments off. It was high time for Texans to get back to work, Abbott said in a press release, pointing specifically to open positions in the restaurant industry. Left unsaid was the over half a million dollars in campaign contributions that Fertitta had funnelled to Abbott over the past few years: Since 2015, Fertitta has poured at least $100,000 per year into Abbott’s political action committee, according to a search of campaign contributions on the Texas Ethics Commission site. The gifts total $650,000 through 2020, making Fertitta one of the governor’s top donors, according to an analysis of all campaign contributions by the National Institute on Money in Politics. In Texas, there are no limits to how much a donor can give to candidates running for public office. (The governor’s office did not respond to a request for comment. Landry’s press team also did not respond to a request for comment.)

Abbott previously took $12,500 from the Texas Restaurant Association PAC, which in May publicly called on the governor to end the weekly unemployment supplement.

In the month of May, a wave of 24 Republican governors across the country have announced that they will stop distributing supplemental unemployment benefits to their constituents in June. A cursory review of National Institute on Money in Politics data found that the majority had previously taken contributions from restaurant executives or owners of local fast food franchising companies. At least eight had received contributions from local affiliates of the National Restaurant Association (NRA), an industry lobby group; many of NRA’s subsidiaries have blamed labor shortages on the payments.

In an interview with a local CBS affiliate, John Barker, president of the Ohio Restaurant Association, said that the industry’s hiring crunch was in part due to workers’ ability to earn more on unemployment benefits than off of them. In mid-May, Ohio Governor DeWine announced that the state would soon stop participating in the unemployment assistance program. The association’s political action committee contributed over $13,000 to DeWine’s most recent gubernatorial campaign, per state filings. (DeWine’s office did not respond to a request for comment. The Ohio Restaurant Association also did not respond to a request for comment.)

Similarly, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee recently announced that the state would also exit the program, which the state hospitality lobby called a “barrier” to hiring. The same lobby group contributed $11,800 to Lee’s most recent gubernatorial campaign. (Lee’s office did not respond to a request for comment. Tennessee Hospitality did not respond to a request for comment.)

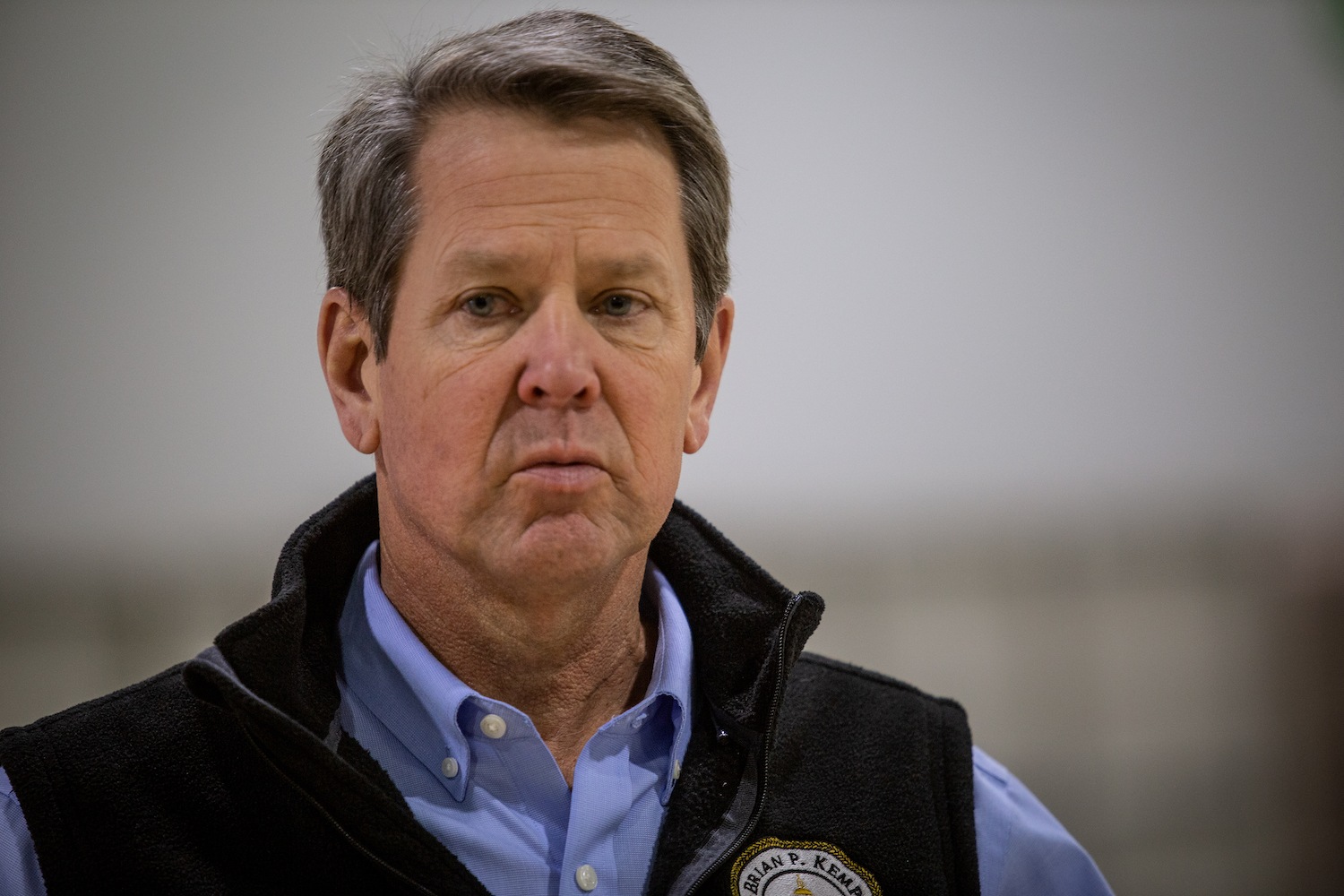

Abbott previously took $12,500 from the Texas Restaurant Association PAC, which in May publicly called on the governor to end the weekly unemployment supplement. (The organization did not respond to a request for comment.) Doug Ducey of Arizona, Brian Kemp of Georgia, and Kim Reynolds of Iowa are among other governors who have also announced the termination of supplemental benefits, while previously having received contributions from local NRA affiliates, per data from the National Institute on Money in Politics. Supplemental unemployment benefits are administered through partnerships between state and federal governments, explains Politico; if a governor opts out, the federal government has little recourse to override that decision.

It’s not news that lobby groups make campaign contributions to candidates for public office, and the hospitality industry is far from alone in calling on policymakers to phase out financial bonuses for the unemployed. However, the restaurant sector’s unique struggles during the height of the pandemic last year, as well as its rocky recovery in the past few months, can lend insight into how businesses of all stripes might be throwing their weight behind certain policies with the intention of accelerating the pandemic recovery, and how those maneuvers could affect workers. Many governors who have announced the termination of pandemic unemployment benefits have cited high job vacancies in the restaurant industry as a motivating factor behind the decision.

“We’re making a lot of assumptions about why folks are on unemployment and are unable to take those jobs.”

According to the Congressional Research Service, the leisure and hospitality sectors saw some of the worst levels of unemployment in April of 2020, when the pandemic was first declared. One year later, the industry is now publicly struggling to restaff as the pandemic wanes. Restaurant owners bemoan ongoing labor shortages, despite a wide range of new efforts to entice applicants, ranging from referral bonuses, higher pay, health care and vacation perks, and more.

Many economists have said that attributing the $300 supplement for mass labor shortages is likely an oversimplification of what’s actually happening. For example, worker advocates have stressed that despite decreasing Covid-19 cases, significant obstacles to finding meaningful employment remain, including lack of childcare access and low pay.

“We’re making a lot of assumptions about why folks are on unemployment and are unable to take those jobs,” said Nicole Marquez, director of social insurance for the National Employment Law Project, referring to the narrative that people are choosing to live off of benefits rather than fill vacancies. For the sake of a long-term recovery, she suggested that lawmakers reject the easy narrative of a “labor shortage,” and instead reflect on policies that could make existing job opportunities more attractive and sustainable for workers.

“People want to work,” Marquez said. “And they want to work in jobs that have good systems and supports in place, like affordable child care, paid family leave, being able to have a job that’s safe and healthy, and livable wages.”

But that’s no excuse to stay jobless, if you ask Governor Abbott.

“The Texas economy is booming and employers are hiring in communities throughout the state,” he said in his mid-May announcement. “At this stage of opening the state 100 percent, the focus must be on helping unemployed Texans connect with the more than a million job openings, rather than paying unemployment benefits to remain off the employment rolls.”