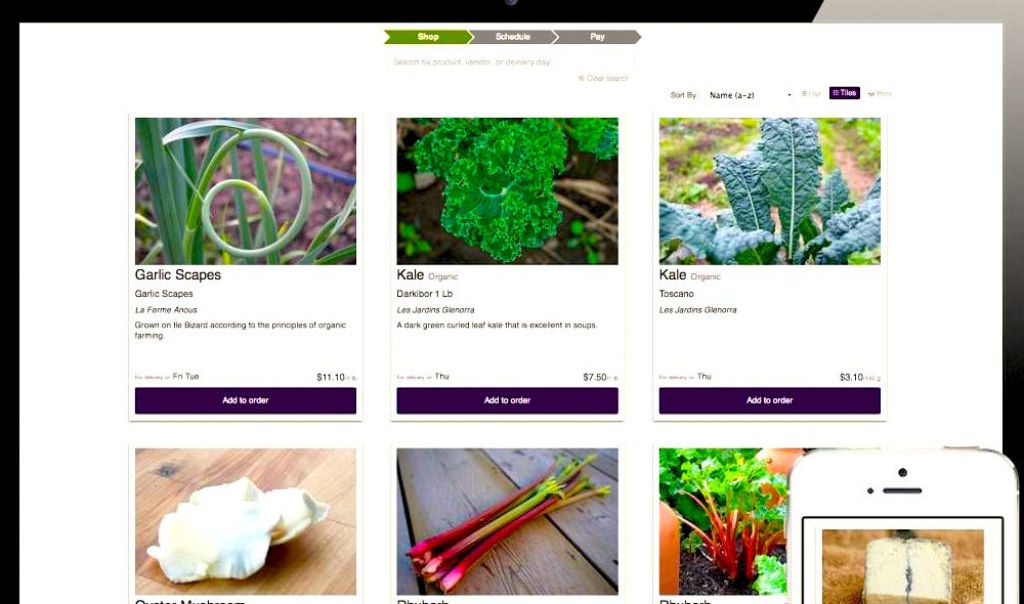

In Canada, Provender‘s kind of a big deal. The app, sort of an Etsy for fresh foods, helps farmers market their products directly to restaurants, while keeping track of invoicing, billing, and growing. CEO Caithrin Rintoul calls it the “OS of agriculture,” but it’s really reminiscent of a dating site: Restaurants that sign up peruse photos of the latest produce—checking out the sexiest new kale, or the hottest radishes in town. Then with the click of a few buttons, they can order fresh greens or a delicate batch of ‘shrooms, and have them delivered within the day. If they’re not satisfied with their produce, they can even rate their bad date, with a review. In the Toronto and Montreal markets, where Provender launched a year ago, it connects 2,000 farmers and restaurants, and some chefs and farmers think of it as indispensable.

Is Provender ready for the big time of one of the big U.S. markets? This summer, Rintoul decided to find out. He chose Boston for his first target—a bit closer to home, not quite as daunting as New York, but with a solid infrastructure of farms to provide food and tech professionals to continue building out the platform. Instead of establishing a small outpost, he moved a good chunk of the 22-person Canadian staff to Boston.

First working out of Techstars, a start-up accelerator program in the city’s old leather district, the team of five is now stationed just outside Chinatown. It would seem their initial test proved the Provender model could work here: the company grew to $210,000 in bookings in its first three months at the accelerator. Rintoul says the bookings rate has been much, much faster in the U.S., “three times the rate of the Canadian market,” and attributes at least some portion of that growth to accessing a more robust network of farmer-partners in this country. He plans to hire on more developers stateside and have the company’s entire tech team Boston-based before the new year.

In late September, Provender invited 30 buyers in to explore its network of goods. Initially, they had 450 products loaded up to sell, a list they’re working to grow slowly by folding in existing markets of buyers and sellers in the Northeast like the Crown of Maine cooperative, slated to join the site this month. Rhode Island Mushroom Company co-founder Mike Hallock is an early adopter who’s started using the product to track some of his sales and inventory. He says it’s the little fixes and accounting in Provender that “add up to a big help.” The cost of using the app varies (from a 4 to 10 percent commission), but Hallock says for him it’s around a five percent cut, or, as he calls it “the cheapest sales force I’ve ever gotten.”

Courting the American farmer

Boston is a more sophisticated food market than Montreal or Toronto, says Rintoul. “There are a lot of longstanding, established farms here that are doing a great job of direct marketing their products,” he says. The challenge for his company is to make it easier for them to succeed—to encourage small-scale New England farmers to quit their side jobs and just “jump in feet first” into farming. “How can we streamline those operations on the farm and just reduce the amount of overhead so people can spend more time farming in a more profitable way, and keep more of those profits on the farm?”

For him, that’s the most important part of the business here, because the average American farmer is roughly 56 years old. American tables are going to need more young blood to meet their growing needs for fresh, local food. Rintoul says these younger farmers are going to want to organize their businesses like they organize everything else: online, and in mobile apps. Rintoul’s competition for farming apps is not steep yet—there’s currently only one other U.S. app connecting farmers to buyers in this way. But competition may not be his only concern. Food entrepreneur Jennifer Goggin, who founded, and has since left a similar operation called FarmersWeb, concedes, “It’s a huge development project to make an e-commerce platform that supports both sides.” (Goggins declines to say why she’s no longer heading the online marketplace and account management tool she built.) There’s the potential for a “chicken or the egg problem: too many farmers and not enough buyers for their products, or too many buyers and not enough product to meet their needs,” she says.

Chefs like James Beard Award-winning Barry Maiden looks beyond Provender’s tech feat to the newfound ease of managing a restaurant’s supply. Maiden says that can be one of the most time consuming parts of starting a restaurant that sources locally. He is a believer in the role farm-to-table can play in helping a restaurant succeed—a lesson he learned at the now defunct Hungry Mother. As he added food from smaller farms, he was putting what he adoringly calls “really, really beautiful product” on the table—produce he says lasted longer, and tasted better. But it took a lot of work and a lot of time to develop his network of trusted producers—at least five years.

“You’re the one making the calls, visiting the farms if you can, to see what they’re all about,” Maiden says. So when Provender arrived in the U.S., he worked briefly as a self-described “evangelist” for the company—preaching the potential merits of Provender to fellow chefs around town, as a consultant. Goggin says what Provender’s doing is more specialized, but wonders whether pricing might be a hurdle. “Prices in general for local foods are higher than you can get importing from the commodity market,” she says. “So they have to prove to chefs the increased cost is worth it for all their ingredients.”

Provender’s app helps farmers do what often seems hardest: manage their businesses in the digital sphere

Provender’s app helps farmers do what often seems hardest: manage their businesses in the digital sphere / Provender

Provender makes its money off of commissions. Rintoul says the margins are about three times better for farmers than traditional distribution models – in which farmers can make as little as 17.4 cents on the dollar. In Provender, buyers can speak directly to farmers, negotiating pricing, setting rates, even telling them what to grow–and agreeing to pay for it before it’s in the ground. Rintoul’s a veteran of both sides of the app’s equation—he’s worked on farms and in kitchens, from his first job on a farm to putting himself through college as a chef.

Big button app wants to run your business

In the long run, says Rintoul, Provender needs to be more than just a marketplace. It needs to help farmers manage their work more easily at many levels. You can see that long-term strategy in the design of the mobile app, with its big buttons, for field-dirty hands, and driving directions for dropping off product. Rintoul says he looks at produce still in the field like inventory in the dirt. Provender’s built a “predictive analytics engine” to track when plants will be ready. And in September, the company partnered with fellow Boston startup Freight Farms. The company’s containers give farmers the option to keep a little extra produce warehoused —guaranteeing a portion of a farm’s goods will weather almost any storm.

Rintoul says Provender is developing and testing new markets in Colorado, Florida and Vermont, which are expected to open sometime this fall or winter / Provender

While Provender is slowly building up and rolling out its American network, working out start-up hiccups like site crashes and high-level employee changes, they’re confident that the Canadian model can work, not just for American restaurateurs, but eventually selling more farm-fresh produce to schools and institutions, too.