Evan Allan

Crop insurance is supposed to cover everybody. But a devastating flash freeze in the Northeast proved it doesn’t.

This story won the 2017 Nelly Bly Cub Reporter award from the New York Press Club (internet category).

This spring, something rare happened to peaches in the Northeast: they all froze. An unseasonably warm winter, followed by a blast of cold air around Valentine’s Day, killed off much of the region’s stone fruit crop. A subsequent April chill meant May flowers were never able to fully blossom into fruit. And it’s not just the peaches that suffered—the nectarines, apricots, and plums never fruited either. Experts estimate that 90 percent of the New England crop was lost, and farms in southern New Jersey, the state’s main peach-producing region, suffered losses estimated at 40 percent.

Pam Clarke of Prospect Hill Orchards in Milton, New York, has never lost an entire stone fruit crop before this season. The farm celebrates its 200th birthday next year, and her grandfather thinks the last loss of this scale happened sometime around 1944 or 1946. Clarke estimates the damages from this freeze at about a third of her farm’s annual income, calling it “a once-in-a-generation event.”

Though you might think the Northeast’s peach output is pithy in comparison to Georgia or California’s, the region’s contribution to our national … G.D.Peach … is actually quite substantial. New Jersey ranks fourth in the nation for peach and nectarine production (about 60 million pounds annually, with a wholesale value for farmers of $30 to $35 million). Further north, in New England, the National Agricultural Statistics Service counted 486 farms growing stone fruit in 2015.

Up to 90 percent of this year’s New England peaches were lost in the freeze

Evan Allan

When a once-in-a-generation weather event freezes an orchard’s assets for the entire season, farmers have to scramble to compensate for the loss. Some cut back on farmstand hours and employees, while others—like Prospect Hill—have to shut down their pick-your-own operations for the season, plant extra vegetables or host events, and put off big purchases like machinery and renovations. All told, a few cold nights in February added up to millions of dollars of damage across the region.

Here’s the thing: there’s crop insurance for just this sort of disaster. Three quarters of cropland in the United States is covered by it, according to USDA and research organization IBISWorld. There are policies available for peaches in many parts of the Northeast. But Clarke doesn’t have it, and neither did any of the other farmers I spoke to about this year’s freeze. The New York State Department of Agriculture and Markets estimates only about a quarter of the peach-producing acreage in the state is insured.

Why are so few peach farmers uninsured, considering that three-quarters of all cropland nationwide is covered?

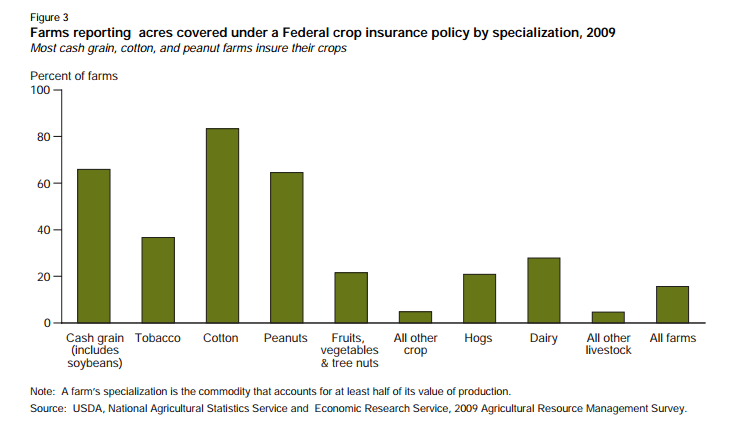

Because it’s insurance, the answer is complicated. But it turns out that crop insurance mostly covers cash crops (corn, soy, wheat, etc.), while vegetables and fruits often slip through the cracks. A 2012 USDA report measuring federal insurance payments found that more than half of farms growing commodity crops had coverage in 2009, while less than a quarter of farms growing fruits and vegetables were covered.

And that’s not because commodity crops fail more often than vegetables. Those numbers are pretty normal. We’ll get into why that happens, but first, let’s look at how we got here.

USDA

If you love ag history, USDA has a great backgrounder on the history of crop insurance here. But the key thing to know is this: Like many large-scale federal programs, crop insurance was born of economic disaster—specifically, the Dust Bowl that devastated U.S. farmland in the 1930s. In response, the Federal Crop Insurance Corporation, which falls under USDA purview, was established in 1938. In its first iteration, the corporation was largely experimental, covering mostly commodity crops in major farm states.

Starting from day one, the program was mainly set up to safeguard large-scale commodity growers, who were major economic drivers in the agricultural sector. There’s nothing inherently wrong with that, but since the 1930s, cropland ownership has shifted considerably. The farms themselves have gotten much bigger, and beyond that, land ownership has consolidated. More than half of farmers these days are farming rented land, and there’s evidence that federal payments actually benefit their landlords. More on that later.

It wasn’t until 1980 that the program was expanded and legitimized by the passage of the Federal Crop Insurance Act, which began subsidizing farmers’ premiums. But opt-in rates remained low, so Congress passed the Federal Crop Insurance Reform Act in 1994.

The Reform Act made a minimum level of insurance mandatory and established inexpensive catastrophic (CAT) coverage. But mandatory participation was repealed in 1996. In 2000, the tides turned again: Congress allowed for an expansion in the role of the private sector.

Only about a quarter of the peach-growing acres in New York State are covered by an insurance policy

Evan Allan

So who’s benefitting now?

Crop insurance started as a risk management tool for commodity growers. USDA has been trying to expand it to cover more ground—literally—since the 1980s. That means offering appealing policies to more farms, covering more acreage, and getting more farmers to sign up for insurance. Has that worked? Depends on who you ask.

Whether or not it’s effective, it’s basically been sold to all these farmers, and their lenders are requiring it, so they’re buying up coverage.

The number of acres covered by crop insurance increased by 40 million to 296 million between 2010 and 2013, according to IBISWorld. By and large, policies continue to be purchased by commodity growers—the report estimates that premiums for insurance on non-commodity crops make up just 15 percent of all payments. While almost three quarters of grain growers reported acreage covered by a federal policy in 2009, only one quarter of fruit and vegetable growers said the same. And the vegetable growers who do opt in are often forced to do so because of circumstance—for example, insurance lawyer Grant Ballard points out that row crop farmers in the South have to prove coverage before securing routine loans.

“Whether or not it’s effective, it’s basically been sold to all these farmers, and their lenders are requiring it, so they’re buying up coverage,” Ballard says.

In order to avoid cutting staff, Fishkill Farms owner Josh Morgenthau increased vegetable production by half. Above, vegetable crew member Megan Mitchell

Evan Allan

It’s not just that the policies skew toward commodity growers—size matters, too, when you look at the farms that actually receive those federal payments. Bottom line: commodity farmers receive crop insurance payments more often than vegetable and fruit farmers, and those farms are getting bigger and bigger.

So while the raw acreage of cropland covered by insurance policies continues to increase, those numbers don’t necessarily indicate that vulnerable small-scale farmers are benefitting from that expanded coverage, too.

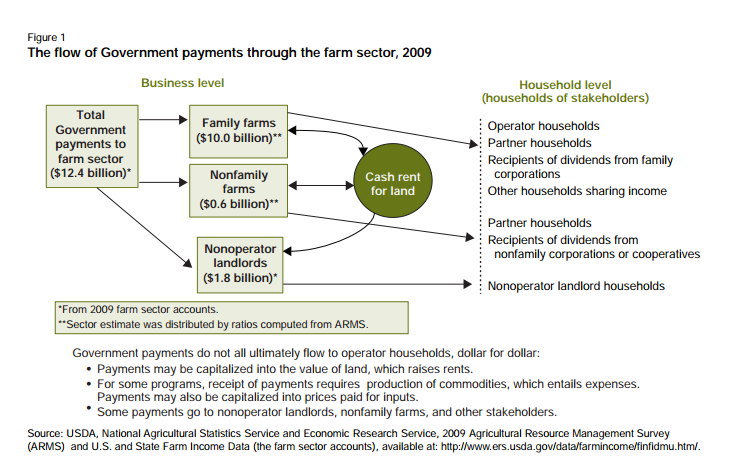

It’s important to resist the urge to imagine a smug commodity farmer cashing in on federal insurance payments, though. A lot of that money actually makes its way back to the people who own the land these farmers are farming on—the agricultural landlords, so to speak.

USDA data from 1999–the most recent available–estimated that 64 percent of cropland was being farmed by someone other than the owner. And not all landlords are farmers who just lease out acreage here and there to neighbors, for example. According to the 2012 report, 57 percent of agricultural landlords are not farmers at all, but they own about 94 percent of rented farmland nationwide. Here’s a diagram of the cash flow.

USDA

But back to Prospect Hill: it’s not a commodity farm, and it’s not required by a landlord or a lender to purchase an insurance policy. Its peach crop falls into the roughly 75 percent of fruits, vegetable, and tree nut acres that are uninsured across the nation.

Here are a couple of reasons why.

Farmers I talked to mentioned that premiums felt too high compared to the protection they offer, and the eligibility criteria can be overwhelming. Only six counties in New York State have coverage plans (though farms outside of those counties can go through a special application process), and an orchard has to be past its third growing season to be considered. Farmers have to use the right rootstock, grow varieties that are well-adapted to the climate, and provide proper documentation.

“Our goal was to do what we could to not have to cut any staff.”

There are so many specifics. And they matter. New York State Ag & Markets estimates that only 460 of the roughly 1,600 acres of peaches being farmed in the state are insured. But a quarter of the acres is not necessarily the same thing as a quarter of the farms—acreage varies considerably from farm to farm. And uninsured peaches doesn’t necessarily equate to an entire uninsured farm, though that’s often the case—crops are covered under separate plans, so an apple tree could be insured and subsidized (and in New York, apples often are, at a rate upwards of 50 percent) while a peach tree six inches away is not eligible.

But even if a smaller farm does have insurance, it’s not necessarily eligible to receive payment every year based on small fluctuations in price and yield, the way its commodity counterparts do. For instance, in New York, policies are available at coverage levels ranging from 50 to 75 percent. Which means that, even if a farmer buys the most expensive insurance package, she’s out of luck until she loses a full quarter of her crop. And that loss minimum goes up to half if she goes with the cheapest policy.

For farms like Prospect Hill, the numbers just don’t make sense. It won’t lose more than a quarter of its crop often enough to justify the high unsubsidized premium, and that leaves it vulnerable when the perfect freeze descends.

Piecing it together without insurance

So what’s a small-scale family orchard to do? Food and agriculture lawyer Jason Foscolo says that many fruit and vegetable farmers use crop diversification (that is, planting a wide variety of crops, some hardier than others) as an alternative risk management method just as they always have. Prospect Hill’s apple and cherry crops made it through the freeze for the most part.

Others, like Josh Morgenthau, farmer and owner of Fishkill Farms in upstate New York, get creative. He protected much of his apple crop by lighting orchard heaters and hiring a helicopter to fly over the orchards. “With a helicopter, if you get it to fly at the right speed, you can essentially act like a ceiling fan and blow down warmer air to keep the orchard a few degrees warmer—often, every degree below a certain threshold, you lose 10 percent of your crop.” But the farm still lost almost all of its peaches.

Due to frost-related crop loss, New York City Greenmarkets are allowing some farmers to purchase wholesale peaches from New Jersey

Evan Allan

In preparation for a tough year, Fishkill expanded its vegetable production by half following the freeze. “Our goal was to do what we could to not have to cut any staff,” Morgenthau says. But it’s still not a perfect solution—he estimates the farm lost 30 to 50 percent of its total fruit output for the year, an estimated six-figure setback.

In New York City, the Greenmarkets are allowing farmers who lost more than 60 percent of their stone fruit to purchase peaches at wholesale in limited quantities from verified farms within the region. Farms bringing in wholesale fruit are required to provide ample signage at their stands. But Clarke points out that variety and quality won’t be the same as it is in a good year. Her customers are used to tons of options, but this year she’s likely to be stuck with run-of-the-mill yellow peaches, and she won’t have much oversight in the picking and sorting process.

But even after using emergency tactics like reselling Jersey peaches and bulking up the events calendar, it’s going to be a tough season for farmers who rely on stone fruit in the summertime. Clarke is trying to remain upbeat, adding that most of her apple crop survived intact. “This is the first summer I can remember where I’ve thought, I just can’t wait for September.”