To achieve long-term success, these employees need vast support networks and help bridging the digital divide.

Every weekday, Quincy Lowery rises at 7:30 a.m., in a room inside his 94-year-old aunt’s house in Queens, New York. He showers, dresses, and takes the bus to midtown Manhattan, where he reports early for his job as a pantry account supervisor. He works at a financial media company, a contracted position with his employer, food service corporation Sodexo. “Being early prevents you from being late, and in this business, you have to be on time,” Lowery said.

Lowery oversees a team of eight in stocking the pantries on two company floors with enough fruit and coffee for 300 people; ordering food for breakfast, lunch, meetings, and catered events; checking that temperature controls for hot and cold foods are in place and that sodas in the vending machines haven’t expired; and making sure there’s ample provisioning of napkins and cups. He takes the work seriously—seriously enough that he earned a promotion from floor attendant just a year after he started. And while this all may sound perfectly mundane, for Lowery, this job was made possible “just by the grace of God”—and is part of his larger “quest to reacclimate to society,” as he put it, after spending 17 years and 10 days in prison for armed robbery.

Lowery belongs to the 8 percent of the U.S. population, and 33 percent of Black American men, according to research released in 2017, who’ve been charged with felonies. For those who’ve served time in prison, reentering society is a fraught and stigma-heavy undertaking. Among the numerous and intertwined reasons: Many businesses, fearing lawsuits if something “goes wrong,” are loath to hire people who were once incarcerated (unemployment for this group is 27 percent and drastically increases the risk of recidivism). This holds true even if companies say their hiring practices do not discriminate and despite the fact that those who’ve done time are often cited as excellent employees. Such discrimination can mean “no matter how hard you work on improving your life and getting on track, you’re excluded categorically without being given a chance,” said Annelies Goger, a fellow in the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institute.

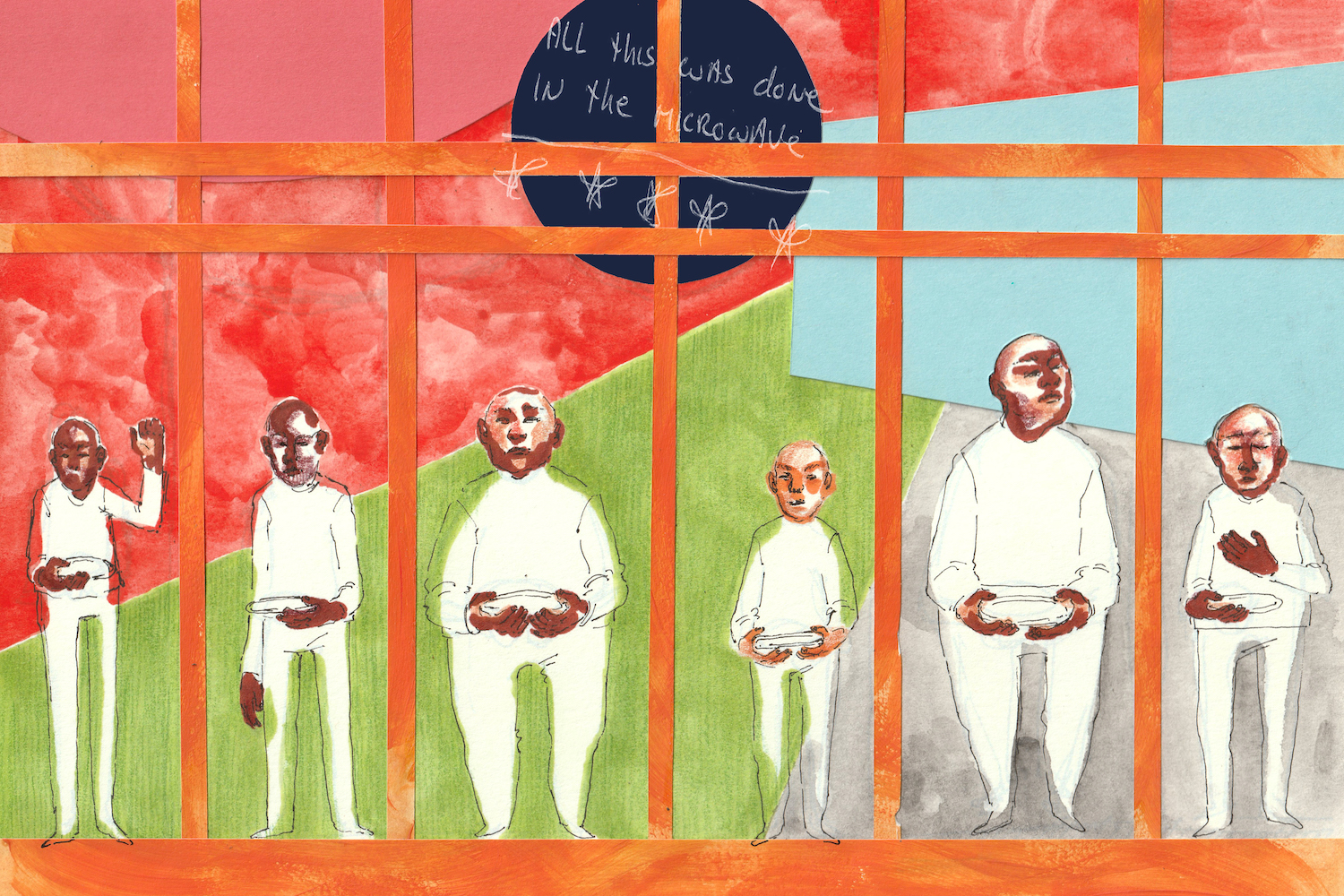

Quincy Lowery, who spent 17 years in prison, is now a pantry account supervisor where he oversees a team of eight for a financial media company in Manhattan.

Lori Hoffman / Courtesy of Quincy Lowery

Significant hurdles certainly continue to make finding employment difficult for the formerly incarcerated. But there has been recent progress, thanks to organizations that help formerly incarcerated men and women acquire job readiness and essential related skills, and have pushed “ban the box” policies to prevent criminal background checks from hindering employment opportunities. Hastened by the effects of Covid on the workforce, restaurants and other food-related businesses are more in need of employees than ever—as well as, in some cases, a public persona that shows them to be sympathetic to the Black Lives Matter movement, according to Ronald Day, vice president of programs and research for New York’s Fortune Society, a nonprofit that supports the formerly incarcerated. Some of that connection comes from George Floyd, points out Goger, who himself found work in restaurants despite a criminal record.

“It’s an interesting dynamic happening in this environment that’s allowing people … to get some opportunities they may not have had previously,” Day said. The trick, though, lies in preparing them to build sustainable careers in hospitality, not just low-paying, dead-end jobs.

Lowery was 16 credits shy of a degree in business management at the University of Virginia when he was arrested in 2000, for a crime he says was actually committed by two associates. After his release from prison in 2018, he was uncertain on how he’d find employment or even how to use a cell phone; technological advancements can pass inmates by while they’re inside, according to Day, and that digital divide is another barrier to finding jobs. Said Goger, “We currently invest very, very little before release [from prison] in career training—digital skills, what’s an email address, how to protect yourself online from bad actors—even though evidence suggests that those investments can really pay off with success in the employment search.”

The trick, though, lies in preparing them to build sustainable careers in hospitality, not just low-paying, dead-end jobs.

Lowery was sitting with his parole officer one afternoon when someone from the Fortune Society stopped by, offering job training. Lowery jumped at the chance to enroll in one of the organization’s fellowship programs. Through these partnered programs, which last between three weeks and, in Lowery’s case, four months, clients get experience in an actual working environment, all while securing “industry-recognizable credentials” such as food handler’s and OSHA certification, as well as first aid and management training. Lowery said he started his internship at $15 an hour, which is minimum wage in New York City.

The point, said Day, is to forge a pipeline to sustainable long-term employment for those who’ve spent time in jail, prison, or are being supervised through probation or parole. Medium- and large-scale businesses—not just hotels and restaurant chains, but kitchens in hospitals, nursing homes, and assisted living facilities—are starting to become more interested in partnering with organizations like Fortune. Some employers are also starting to pay a decent wage, offer benefits, and no longer expect people “to come in with the skills and fundamental training they want—sometimes people have to grow with the company.” Day said that hiring managers are beginning to recognize this is exciting. “If Covid opened our eyes to anything, it’s the fact that we can do work differently than we’ve done previously and employers are reconsidering some of the restrictions they may have imposed in the past.”

Organizations with little past intentional effort to work with formerly incarcerated people are also starting to see the population in a new light. The National Restaurant Association Educational Foundation in 2019 set up a program with a variety of partners to train formerly incarcerated young adults aged 18 to 24—and, more recently, all adults—called Hospitality Opportunities for People (Re)Entering Society (HOPES), with nearly $8.5 million in grant money from the Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration. Covid stymied its operations, but the young adult program has so far enrolled 150 men and women. The adult program aims to get 430 signed up when enrollments open in January 2022, in four states where departments of corrections “were already doing culinary and food service work and were interested in, not just release but reentry and in partnering with us,” said the foundation’s director of workforce development, Patricia Gill. She notes that hospitality is an industry that “mostly doesn’t care what you’ve done before; if you can come into a restaurant and work hard, you can do well.” Like Fortune’s fellowships, the intent with HOPES is to help build true careers with opportunities for advancement. Although some HOPES participants have found that food service jobs are not quite right for them and taken their newly-acquired skills over to jobs in other industries, most have stuck hospitality out so far. “The majority are working as prep cooks, servers, and we’ve got a guy who’s pitmaster at a barbecue place,” Gill said.

The National Restaurant Association Educational Foundation started the Hospitality Opportunities for People (Re)Entering Society (HOPES) in 2019 to train formerly incarcerated young adults aged 18 to 24. Participants tour a MOD Pizza location and learn about different jobs of the business, from dishwashing to pizza-making.

HOPES participants get on-site training at partner restaurants, fast food chains, and hotels, as well as career exploration, connections to transportation, work clothing, transitional housing, and childcare. They also get occupational skills training and credentialing, and receive essential guidance about workplace responsibility from HOPES-partnered community organizations. The program offers a year of follow-up after it’s over, to help participants maintain their skills and get new training as necessary. HOPES also tries to intervene early when challenges arise, hoping to help prevent turnover. For example, said Gill, “We want to make sure a participant has a transportation plan and the employer knows what it is and can work to help them with it. But also on the other side, a lot of employee scheduling and payroll is done online through the phone, and we want to provide support for participants to be able to access those systems.”

Harley Blakeman, himself formerly incarcerated, founded online employment agency Honest Jobs in 2018 to offer up a more tech-based way for employers and potential formerly incarcerated employees to find each other. He says breaching the digital divide in this arena can help employers who are reluctant to hire the formerly incarcerated feel more secure in deciding to do so. “We can help them avoid negligent hires,” he said. “Our technology can consider the crime each applicant has”—it reads job descriptions and identifies duties, then compares key words to a person’s criminal history—and makes sure it’s suggesting jobs that are appropriate, i.e., not pairing a person with a record as a sex offender with a job in a school cafeteria.

Working with 10,000 clients and 400 companies, Blakeman is not focused exclusively on hospitality jobs, but it’s nonetheless quite common for his organization “to work with hotels and restaurants, and we often find that they are open to hiring people with records,” he said. His biggest restaurant placement success so far has been with the ZOUP! Chain in Ohio, which recently hired half a dozen of Blakeman’s clients.

“If Covid opened our eyes to anything, it’s the fact that we can do work differently than we’ve done previously and employers are reconsidering some of the restrictions they may have imposed in the past.”

Blakeman sees digital solutions as essential to helping the formerly incarcerated in other work-related capacities. He mentions a debit card company called Clair, which allows employees to get paid at the end of every shift. “A lot of people need paychecks now to pay the electric bill and can’t wait two weeks,” he said. He’d also like to see companies providing transit solutions: “Offer people an Uber or Lyft stipend for their first two paychecks, then add $300 to each paycheck for two months, so they don’t end up in a situation where they can’t afford to ride”—this partially in response to the lack of driver’s licenses among some formerly incarcerated people.

Goger would like to see policy reforms that allow technology training inside prisons, where it’s typically banned for security reasons. “We want everyone to have access to those tools to make sure they have some preparation before they leave,” she said. But also important are programs such as Fortune’s, which she says build up supportive networks for their clients. “Having someone who can vouch for you is a critical part of the equation, and so is that work experience and learning how to manage different workplace cultures,” she said.

Meanwhile, back at Fortune, one of Day’s largest partners—in fact, one of the largest employers in New York State—is the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which oversees, among other transportation hubs, five national and international airports. So far, Fortune has had success placing 38 clients with JFK Airport’s AirTrain. Finding them work with all the airports’ food vendors would seem like a no-brainer. But getting clients hired there presents yet another in a long, long list of employment challenges: Working inside the airport proper requires TSA security clearance that precludes hiring people convicted of certain offenses.

Of course this is but one of the many challenges still facing the formerly incarcerated in their job hunts. By Day’s own admission, “I’m not suggesting that across the board restaurants, especially some who might have exploited individuals in past and not just the justice involved, are wiser or have come to terms with the fact they need to change, but some of the larger businesses are interested in working with organizations like ours.” Little by little, though, Day and his counterparts at other organizations are “trying to make some inroads” that ensure job-seekers can find meaningful, lasting work on the other side of incarceration, even in places that might now seem out-of-reach.