Graphic by Alex Hinton | Source Images: iStock

The EPA is investigating whether it’s discriminatory for Eastern North Carolina’s hog waste operations to be centered in poor Black, Latino, and Indigenous communities.

Residents in Eastern North Carolina’s Duplin and Sampson Counties have to learn to live in close proximity to hog waste. Sometimes it’s just the stench of it, but depending on where they live, it could also mean that the waste is sprayed onto their homes, leading to health issues and attracting an array of pests–especially during the summer when flies are already in abundance.

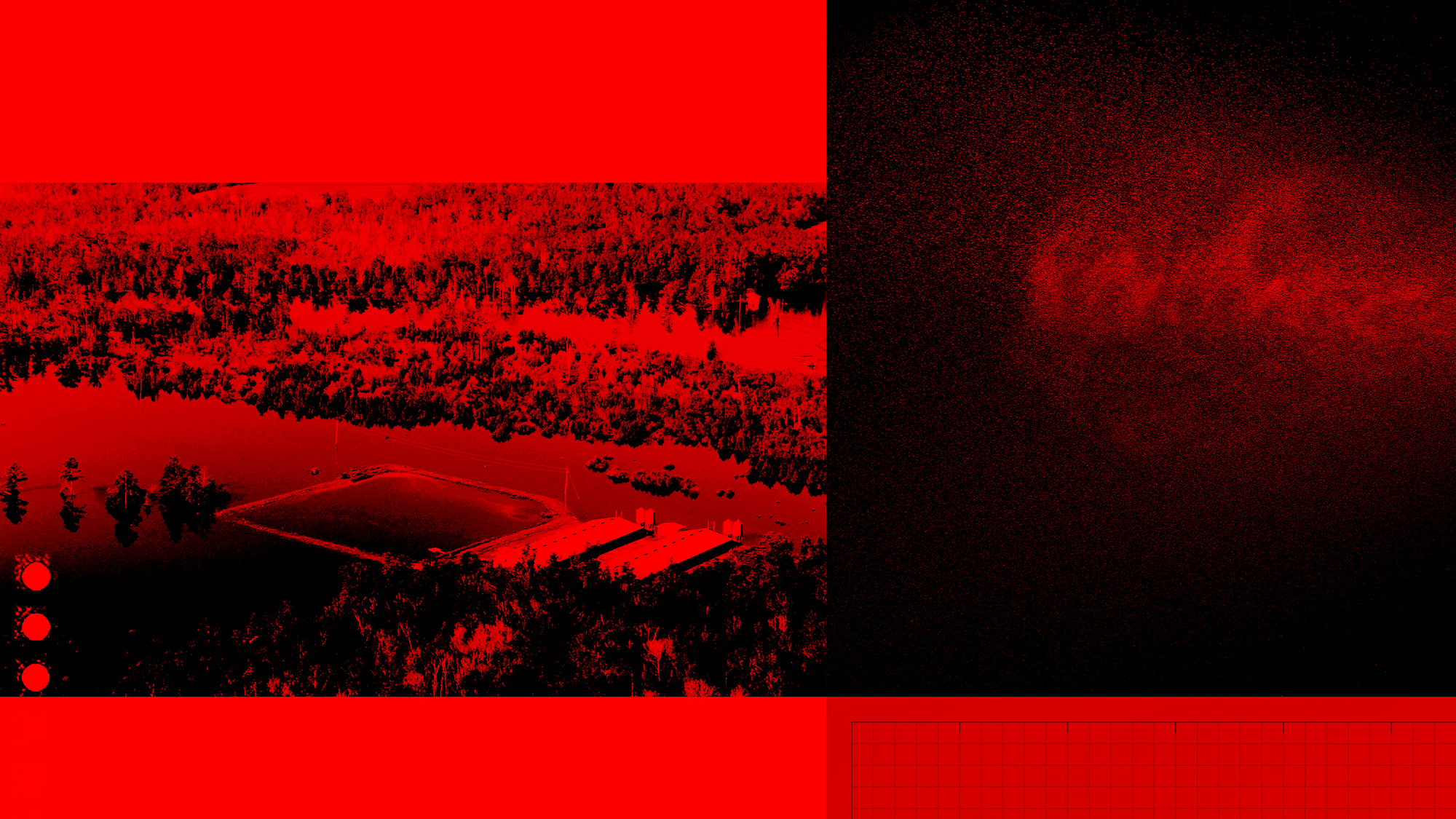

These intolerable conditions are actually made possible by the state. For decades, North Carolina law has allowed industrial swine operations to dispose of hog waste using lagoon and sprayfield systems, which store hog feces and urine in open-air pits before spraying the waste onto fields. In Eastern North Carolina these crude operations are now changing. But not for the better.

In March of 2021, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) issued permits to four Smithfield Foods-owned hog farms, allowing them to invest in biogas, a lucrative waste management system in which methane is trapped within sealed lagoons, in what is known as anaerobic digesters. The trapped methane gas is transported, processed, and sold by Smithfield as a form of renewable energy. A second open-air lagoon stores the waste from the digester, which is sprayed onto fields, then spackling nearby homes.

There is no skirting the fact that the people who live in America’s most polluted environments are people of color and the poor. Whether it’s a chemical plant in East Los Angeles or a factory farm in Eastern North Carolina, communities of color are routinely targeted to host operations that have negative environmental impacts.

“Everything this industry does is sold to us as progress, but in practice it looks like pollution.”

North Carolina’s hog waste operations are concentrated in Duplin and Sampson Counties, where Black, Latino, and Indigenous residents make up nearly half of the population and where the average poverty rate is over 20 percent, well above the national average. According to Sampson County resident Sherri White-Williamson, DEQ permits environmental injustice by allowing these hog waste operations to pollute these communities.

Williamson-White left Sampson County in the 1970s to attend college, but she always knew she’d come back home. It would take decades, but she finally returned to North Carolina after retiring from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). After returning, she co-founded the Environmental Justice Community Action Network (EJCAN), a non-profit focused on environmental justice.

Environmental justice activism emerged in Eastern North Carolina in the 1980s when Black residents of Afton fought state officials’ decision to use their town as a dumping ground for hazardous waste. Afton residents ultimately lost their fight, but a movement was born. That early struggle also produced one of the first reports that detailed how race was more strongly correlated with the placement of a hazardous-waste facility than any other single factor. Fast forward about 40 years and now the EPA has an Office of Environmental Justice, which says it seeks the “fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”

It should come as no surprise that concentrating the state’s hog waste in a region that is low-lying and flood-prone remains a bad idea.

Advocates in Easern North Carolina argue that their communities continue to be subjected to environmental injustice, but now it’s painted as advancement. The four DEQ-issued permits are part of a much larger operation called the Align RNG biogas project, a partnership between Smithfield Foods and Dominion Energy that will result in a 30-mile pipeline network among hog waste lagoons on 19 farms in Duplin and Sampson Counties.

A spokesperson for Smithfield told The Counter that Align and Smithfield’s goal is to “provide the infrastructure to allow farms that desire to install digesters to do so.” In marketing, Smithfield sells its biogas operations as “clean technology” that will produce “renewable energy” and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, protect the climate, and make the air better.

On paper, it sounds like progress, a way to make use of the billions of gallons of waste that North Carolina’s nearly 10 million hogs produce each year. However, these biogas operations still rely on the use of primitive hog waste lagoons. Older lagoons are unlined, leaving noxious gases and microbial pathogens like salmonella to leak into the ground. The hog waste is meant to break down as the liquid evaporates, but there is often spillover, so farmers spray the slurry into nearby fields. Not only does waste get onto people’s homes, but it washes into the local watershed, killing fish and “choking the state’s rivers with excess nitrogen and phosphorus,” Pacific Standard reported.

“Everything this industry does is sold to us as progress, but in practice it looks like pollution,” White-Williamson told The Counter.

Graphic by Alex Hinton | Source Images: iStock, Ted Richardson/For The Washington Post via Getty Images, The New York Times

The rise of industrial hog farms—and pollution—in North Carolina

Like many Black families in Eastern North Carolina in the 1960s, White-Williamson’s grandfather and other family members raised hogs. The animals roamed the fields near their home and were fed corn and kitchen scraps, a far cry from the factory farms that have since overtaken Duplin and Sampson Counties. These rural communities are now the top hog-producing regions in the state and the country.

“Starting in the ‘80s and early ‘90s, there was just a constant increase in industrialized farms in Eastern North Carolina and these operations were often slammed into low-income communities and communities of color, and these communities haven’t been the same since,” White-Williamson said.

Between 1985 and 1998, North Carolina moved up the ranks in hog production among U.S. states, becoming the second-highest behind Iowa. In large part, this was made possible by former state senator Wendell Murphy, the man credited with “building the modern pig business.” In the 1960s, Murphy founded Duplin County’s Murphy Family Farms. The company, which became one of the largest hog producers in the nation, was sold to Smithfield Foods in the 1990s.

This was around the same time Murphy sponsored a bill that, for seven years, allowed for the proliferation of concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs)—otherwise known as factory farms—centered in Eastern North Carolina. In 1992, Smithfield Foods opened the world’s largest meat processing plant in Bladen County. The company is now the world’s largest pork producer and owns or operates more than 200 hog farms in North Carolina, in addition to six feed mills and hundreds of contract farms.

During Hurricane Florence in 2018, at least 110 lagoons in the state either released hog waste into the environment or were at “imminent risk” of doing so.

Reporting on Murphy tends to focus on his humble beginnings and his role in the expansion of North Carolina’s billion dollar industrial hog farming industry, rather than on the way these operations wreak environmental havoc in a region now at the center of multiple ecological disasters.

In the early ‘90s, residents warned officials about environmental impacts, to no avail. The hog industry was becoming valuable—an industry worth more than $1 billion in North Carolina. And as it grew, so did the waste—to disastrous results. In 1995, the worst hog waste spill in North Carolina history occurred, followed by Hurricane Floyd in 1999, which broadly contaminated groundwater, wells, and rivers with waste from hog farms. State officials vowed to do something and came up with an agreement with Smithfield, but it “lacked teeth”—to the great detriment of residents, mostly communities of color. It should come as no surprise that concentrating the state’s hog waste in a region that is low-lying and flood-prone remains a bad idea. During Hurricane Florence in 2018, at least 110 lagoons in the state either released hog waste into the environment or were at “imminent risk” of doing so.

Graphic by Alex Hinton | Source Images: iStock, uscourts.gov

An uphill battle for communities of color fighting back

In 2018, the North Carolina Medical Journal published an issue devoted to environmental health in the state. The published findings confirmed what the residents of Duplin and Sampson Counties already knew: Those who live near hog CAFOs have higher death rates of all studied diseases, and rates of infant mortality, anemia, kidney disease, septicemia, and tuberculosis were higher in communities with hog CAFOs.

“Communities don’t have the resources that the agricultural industry has, so the industry has been able to sell a story of prosperity and economic development and jobs and all the good things that you would hope from an industry. The community knows these things are not all true, but it’s hard to counter the level of money that the industry can use to support decision makers who are more likely to support what the industry wants rather than considering the needs and the health of the local community members they are supposed to be representing,” White-Williamson said.

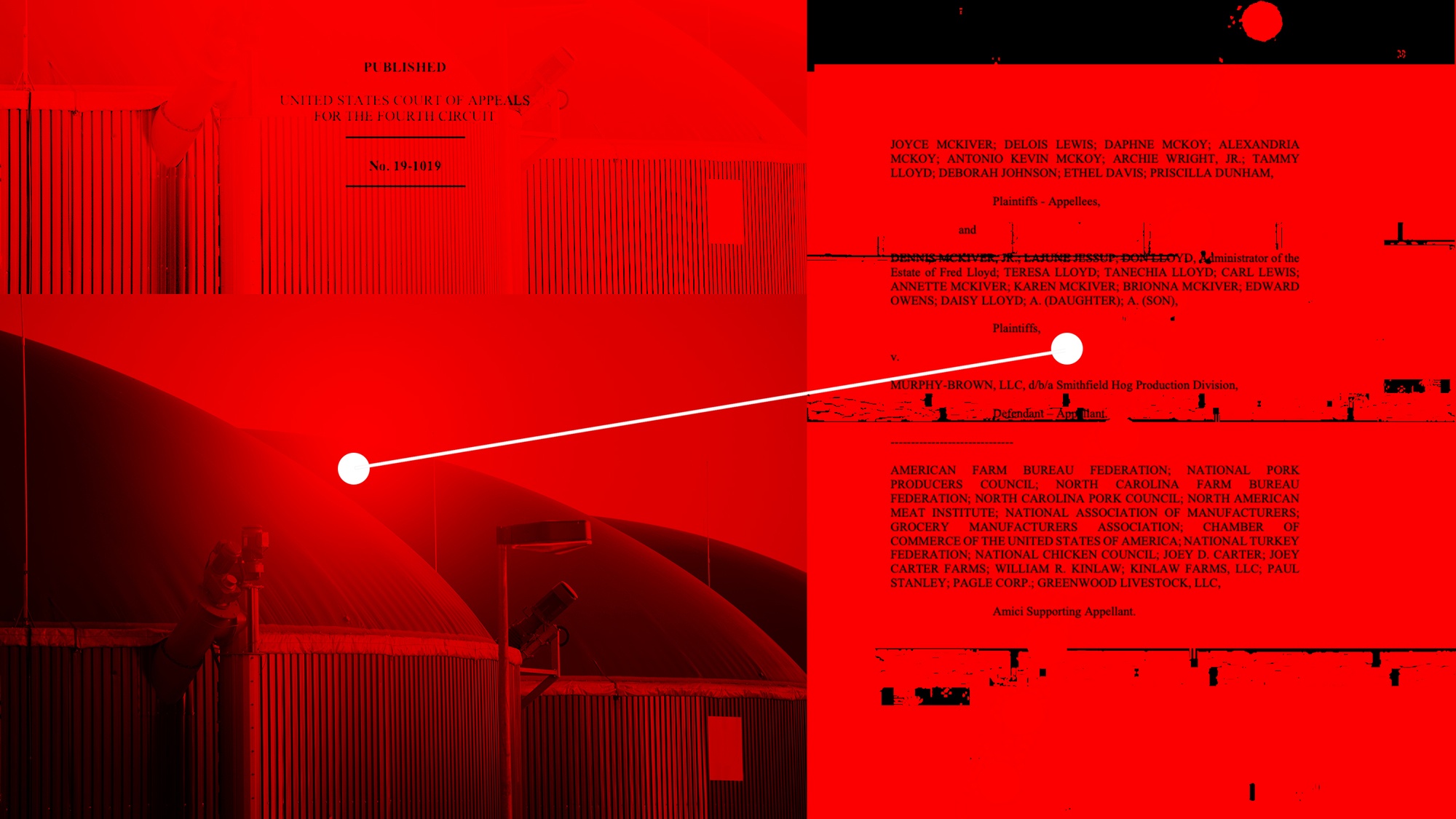

Still, local residents put up a good fight against agricultural operations in the state. Beginning around 2014, 26 federal nuisance lawsuits were brought against Smithfield and its subsidiaries by more than 500 majority Black plaintiffs. Overwhelmingly, these were longtime residents who’d grown sick of the flies, buzzards, squealing, stench and other conditions typical of living near hog operations. In 2018 and 2019, juries awarded 36 plaintiffs a total of almost $550 million, a number that was reduced to about $98 million because of a state law that caps punitive damages.

“Communities don’t have the resources that the agricultural industry has, so the industry has been able to sell a story of prosperity and economic development and jobs and all the good things that you would hope from an industry.”

Also in 2014, the Waterkeeper Alliance, Rural Empowerment Association for Community Help, and the North Carolina Environmental Justice Network filed a complaint under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 against the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality with the EPA’s Office of Civil Rights, alleging that DEQ’s permitting and oversight of swine CAFOs has a racially discriminatory impact on Black, Latino, and American Indian North Carolinians.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. As a recipient of federal funds, DEQ must adhere to Title VI of the act, which prohibits discrimination in any program or activity that receives federal funds or other federal financial assistance.

In 2018, the groups reached a settlement agreement with DEQ that included air and water quality testing in select counties and a pledge by the agency to “develop a more robust Title VI program governing all DEQ activities, including a method to assess potential community impacts related to agency decisions.” But DEQ is at the center of yet another complaint alleging racial discrimination.

In September of last year, the Southern Environmental Law Center filed a civil rights complaint with EPA on behalf of the Duplin County Branch of the North Carolina Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the North Carolina Poor People’s Campaign, alleging that DEQ’s issuance of Smithfield’s biogas permits would have a disproportionate impact on communities of color in Duplin and Sampson Counties. The EPA, in connection to the complaint, is also looking into whether NC DEQ has a public participation policy and process that is consistent with Title VI and the other federal civil rights laws.

Addressing Smithfield’s biogas permits with a civil rights complaint may seem like an unusual strategy, but according to Blakely Hildebrand, a senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center who filed the recent complaint against DEQ, traditional legal tools like the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act provide loopholes for agricultural operations.

“Options are very limited when it comes to addressing the racially disparate impact of agricultural operations, but the Title VI complaint process with the EPA is a legal tool that communities do have at their disposal to bring to light environmental injustice.”

“Options are very limited when it comes to addressing the racially disparate impact of agricultural operations, but the Title VI complaint process with the EPA is a legal tool that communities do have at their disposal to bring to light environmental injustice,” Hildebrand said.

One of the ways that an agency can violate Title VI, Hildebrand added, is by making policy decisions that have a discriminatory impact.

DEQ told The Counter it is committed to the “fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all North Carolinians.” The agency said that since 2017, it has given significant priority to compliance with Title VI requirements, particularly with regard to animal waste permitting.

For the four biogas permits, DEQ said it conducted enhanced public outreach, an environmental justice analysis, and held a public meeting and comment period to provide an opportunity for community input on the four farm modifications.

“DEQ staff reviewed the concerns raised by the public and carefully evaluated the permit modifications to address the concerns within the existing authority of the agency and applicable state rules and regulations,” a DEQ spokesperson said in a statement.

Graphic by Alex Hinton | Source Images: iStock, Getty Images

The pollution caused by hog waste lagoons is in some ways preventable. After Hurricane Floyd in 1999, Smithfield said it would abandon its lagoon and sprayfield systems and develop and implement cleaner, more sustainable hog waste technologies. The company followed through on its word–kind of.

Smithfield invested $15 million to research how to upgrade its waste management systems, which led to a 2013 report concluding that a system developed by a North Carolina company called Terra Blue met existing industry regulations and could improve existing hog farming operations and be incorporated into new or expanded hog farms. The Terra Blue system involves replacing the old lagoons with open tanks, which helps protect groundwater and land and surface waterways. But Smithfield chose not to adopt the technology, claiming it did not meet criteria for “economic feasibility.”

Flood waters surround a hog farm in Eastern North Carolina after Hurricane Floyd on September 18, 1999.

AFP via Getty Images/John Althouse

Instead, it appears Smithfield has chosen to pivot to biogas operations. Not only does this keep the old lagoon system in place, it increases water pollution because it leads to higher concentrations of ammonia in the sprayed waste. Smithfield will profit from these conditions while claiming to address greenhouse gas emissions, a serious environmental issue its own industry is significantly responsible for. According to Hildebrand, very little about Smithfield’s biogas operations is “clean” and “green.”

“The hog industry decided that the cheapest way to dispose of billions of gallons of hog waste was to put it in a pit in the ground and then spray it on a nearby field,” Hildebrand said. “That process produces methane, and now the industry is proposing a ‘solution’ that would cap the open air pits with the goal of reducing methane emissions. I don’t dispute that wanting to reduce emissions is a good thing, but they’re trading a methane emissions problem for an ammonia emissions problem without ever really addressing the pollution and public health crisis that has been playing out on the ground in Eastern North Carolina for decades.”

Smithfield maintains that their biogas operations in North Carolina are designed to support communities and the environment by making existing hog farms more sustainable, but reporting has shown that they are difficult to sustainably maintain. The company also asserts that their biogas permits were approved following a “robust and unprecedented permit and outreach process.”

For decades, North Carolina law has allowed industrial swine operations to dispose of hog waste using lagoon and sprayfield systems, which store hog feces and urine in open-air pits before spraying the waste onto fields.

“Turning methane from hog farms into clean energy is an innovative, sustainable practice and an absolute win for North Carolina, the communities where Smithfield operates, and the environment,” said Jim Monroe, Smithfield’s vice president of corporate affairs. “Manure-to-energy programs are critical to making hog farming, which is vital to the economic health of Eastern North Carolina and plays an imperative role in feeding the country, more sustainable.”

University of Iowa professor Silvia Secchi studies the environmental impacts of agriculture. She told The Counter that strategically, Smithfield’s shift to biogas is a smart move. By using climate change to rationalize its push for biogas operations in North Carolina and other states, Smithfield is making it more difficult for local communities to push back on its operations.

“Agriculture is one of the least regulated industries in the United States, so these biogas operations are going to be an uphill battle for communities because any regulations will always be subject to modifications that favor the agricultural industry,” Secchi said.“It screws with communities of color on the front end by telling them they have to put up with biogas operations because it’s a climate change mitigation solution, and it screws with them on the back end because it isn’t actually a solution and the climate change created by the operations will disproportionately affect them,” Secchi said.

Addressing false narratives

In January of this year, EPA announced that it is investigating the discrimination complaint filed last year against DEQ on behalf of organizations in Sampson and Duplin Counties. William J. Barber III sees this as a “promising development.”

Barber grew up in Eastern North Carolina and is currently the director of climate and environmental justice at the Climate Reality Project founded by former vice president, Al Gore. Barber is also the son of Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II, leader of the Poor People’s Campaign, a North Carolina movement that confronts racism, poverty, environmental injustice, militarism, and “the distorted moral narrative of religious nationalism.” They’re also one of the organizations behind the complaint against DEQ.

As co-chair of the group’s ecological justice committee, William J. Barber III told The Counter that he has encountered families who have been in Sampson and Duplin Counties for decades, leading multiple generations to experience the kind of adverse health effects that have become common for those living in close proximity to hog CAFOs–including asthma. Barber said the environmental hazards wrought by agricultural companies in the Southeast are a “pressing, critical issue” that must be addressed.

“Part of the work in North Carolina is to address false narratives,” Barber said. “These corporations try to pit environmentalists against farmers or make it appear as though we oppose small family farms. That couldn’t be further from the truth. These biogas operations are not run by small family farms; corporations are running these operations. Often, they are foreign corporations that are actually getting premiums to basically pollute American communities and call it green energy.”

Smithfield Foods was purchased in 2013 by Chinese conglomerate WH Group, and the company’s ever-growing footprint in North Carolina is openly embraced by elected officials. In 2018 when Smithfield opened a 500,000-square foot facility in Tar Heel, farmer Steve Troxler, a Republican and the state’s Commissioner of Agriculture and Consumer Services, applauded the company for its “continued support” of North Carolina’s agricultural industry.

North Carolina’s stance on environmental issues is muddled. At the beginning of the year, Democratic Governor Roy Cooper issued an executive order to establish new carbon reduction emissions goals to reduce pollution, create good jobs, and protect communities. Barber said the executive order creates an opportunity for a more “robust conversation” about the connection between climate and equity, but that it’s also time to move beyond talk.

“We have to really push decision makers beyond conversation and beyond abstract claims,” Barber said. “We have to have a real plan for addressing climate injustice that should include taking a look at our public participatory process for agriculture permits and updating our cumulative impact assessments. [DEQ] looked at the biogas permits with a minimal kind of lens, without thinking holistically about the harms to the community related to public health, environmental impacts, and their larger contributions to the climate crisis.”

In a statement to The Counter, Cooper’s press secretary Jordan Monaghan said that state environmental regulators must follow the law to determine permits and protect the health and safety of North Carolinians.

“[DEQ] looked at the biogas permits with a minimal kind of lens, without thinking holistically about the harms to the community related to public health, environmental impacts, and their larger contributions to the climate crisis.”

Iowa is the top pork-producing state in the nation and it grapples with many of the same environmental issues as North Carolina–though the populations harmed by hog operations in Iowa are decidedly different than in North Carolina, Secchi explained.

“Iowa is predominantly white and we have CAFOs pretty much all over the state. It’s different in North Carolina because the CAFOs are concentrated in certain parts of the state—not just because those areas have cropland to dispose of the manure,” Secchi said. “There is very clear evidence that these areas were chosen for operations because local communities don’t have the same pull with legislators as white communities. I think we can deduce that they decided these communities were poor and marginalized and operations would be met with less resistance.”

This is why agencies like DEQ are so important. As the department in charge of North Carolina’s environmental resources, part of the agency’s stated mission is transparency and holding bad actors accountable. DEQ is also supposed to serve as a community’s defense against serious environmental hazards. But White-Williamson said the agency has just been “checking boxes” when it comes to low income communities and communities of color.

“In this region, there are 18-wheelers constantly going to these industrial facilities to pick up and deliver feed or animals to swine and poultry operations, causing diesel emissions. There are trains in communities often sitting for days waiting to be loaded or unloaded,” White-Williamson explained. “The totality of all of these impacts was not considered when the biogas permits were issued. For our communities, that’s deeply problematic. It’s one environmental hazard on top of another.”

“I think we can deduce that they decided these communities were poor and marginalized and operations would be met with less resistance.”

Outside of the four farms revealed as part of the permitting process, the Align RNG biogas project has not disclosed to DEQ or the public the full list of participating farms and their locations. In January of last year, 30 Democratic legislators sent a letter to DEQ asking the agency to deny water quality permits for farms who plan to participate in the project. Smithfield told The Counter that with the exception of “a few farms” that it owns, the majority of the farms that will have the opportunity to be part of the Align project are owned by independent farmers and because the permitting process is public, “their participation will be known by both DEQ and the public.” Beginning April 5, DEQ started hosting a series of public hearings regarding general biogas permits.

As for the racial discrimination complaint against DEQ now being investigated by the EPA, a spokesperson for the agency said the decision to pursue an investigation doesn’t necessarily mean the allegations are true or that Title VI violations have occurred.

White-Williamson is concerned that Michael Regan, the administrator of the EPA, previously served as the secretary of DEQ. However, a spokesperson for the EPA told The Counter that the administrator would not be directly involved in this matter or any other Title VI matter because the External Civil Rights Compliance Office is part of the Office of General Counsel and does not report directly to the administrator. Still, White-Williamson is unsure of how the complaint will play out—and she’s concerned about the future of her county.

“This is more than just a story about biogas,” White-Williamson said. “This is really a story about power and who makes the decisions in these counties. It seems that everything bad finds its way to places where communities are already overburdened by other polluting facilities. Community members are really tired of having their health and dignity disregarded by the powerful.”