The Mediterranean diet, which encourages olive oil, fruits, vegetables, and seafood and discourages red meat and sugar, is often touted as a heart-healthy ace-in-the-hole. But its benefits may be confined to the wealthy and well-educated, according to a new study by Italian researchers that followed almost 19,000 men and women over the age of 35 across various education levels and income brackets over four years. The study did not include any people who already had heart disease or diabetes, so the researchers weren’t able to gauge the diet’s effect on people with existing conditions. This is the first time researchers have studied the effects of the Mediterranean diet across socioeconomic groups.

The researchers measured the degree to which each participant said they followed the diet and compared those numbers against overall incidence of cardiovascular disease. They found that while staying on the diet reduced heart disease by 15 percent overall, those numbers didn’t hold true for the entire population of participants. When they filtered the results by income and education level, the diet turned out to benefit wealthy people by quite a lot—and poor people, not at all.

More specifically, the researchers measured adherence to the diet on a nine-point scale, with a higher score marking better compliance. So if you followed the diet for the most part, but maybe ate more red meat and butter than was recommended every once in awhile, you might score a 6 or 7. What the researchers found was that higher-educated and higher-earning groups (which included some overlap) saw benefits that others did not. For college-educated people, a two-point increase on the adherence scale correlated with a 57 percent decrease in rate of cardiovascular disease. They also found that the highest income bracket (people making more than 40,000 Euros per year) saw a 61 percent decrease in disease prevalence for that same two-point interval. However, “no relationship” was found in low-income and low-education groups who followed the diet to the same degree.

Before we get into the nitty gritty, it’s important to note that the study followed people for a relatively short period of time and researchers saw only 256 instances of cardiovascular disease over four years. That means just 1 percent of study participants experienced some sort of heart-related medical event; by contrast, 6 percent of people in the European Union are living with some kind of cardiovascular disease. (In the U.S., about a quarter of the population suffers from some form of heart disease.)

Still, how can it make sense that two groups of people following the same diet can see such different results?

The answer may lie in the quality and variety of the foods people are eating. When asked how many different types of fruits and vegetables they had eaten over the last two weeks, people with more education reported a wide variety of choices. They also tended to eat more whole grains and seafood. The researchers refer to the package of foods eaten as a “bundle,” and they hypothesize that within the diet, some bundles may be healthier than others.

They also acknowledge that there are a lot of factors that might affect heart disease that we still know very little about. High-income people, for instance, bought more organic foods. But there’s not much evidence to indicate organic vegetables have anything to do with hypertension. Similarly, highly educated people also ate more fiber, Vitamin D, and calcium. There’s no way to know if any of those differences are significant.

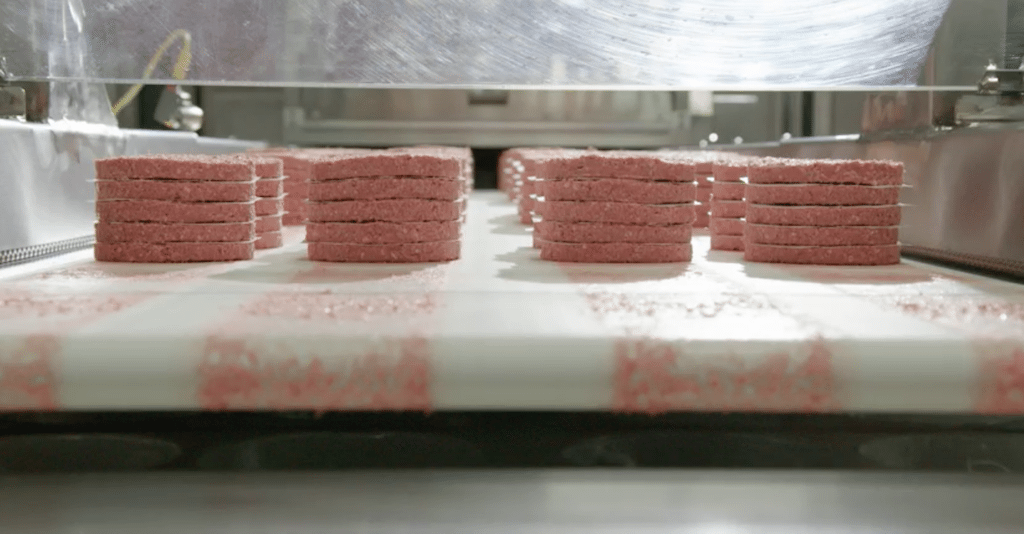

The researchers also found differences in the ways people said they prepared their food. “The nutritional properties of foods are closely dependent on external influences such as food processing and cooking procedures,” they explain. Translation: a deep-fried carrot dipped in Ranch is not the same thing as a raw one dipped in hummus.

High-education and high-income people tended to cook their vegetables in ways deemed “healthier” (steaming instead of frying, for instance). But they also tended to use “hazardous” cooking methods for beef, such as grilling at high temperatures or roasting.

The results aren’t necessarily an indication that the Mediterranean diet works for some people and not for others over the course of a lifetime. But they do seem to add another log to the “diet isn’t everything” fire that’s been burning in public health and nutrition circles for a while now.