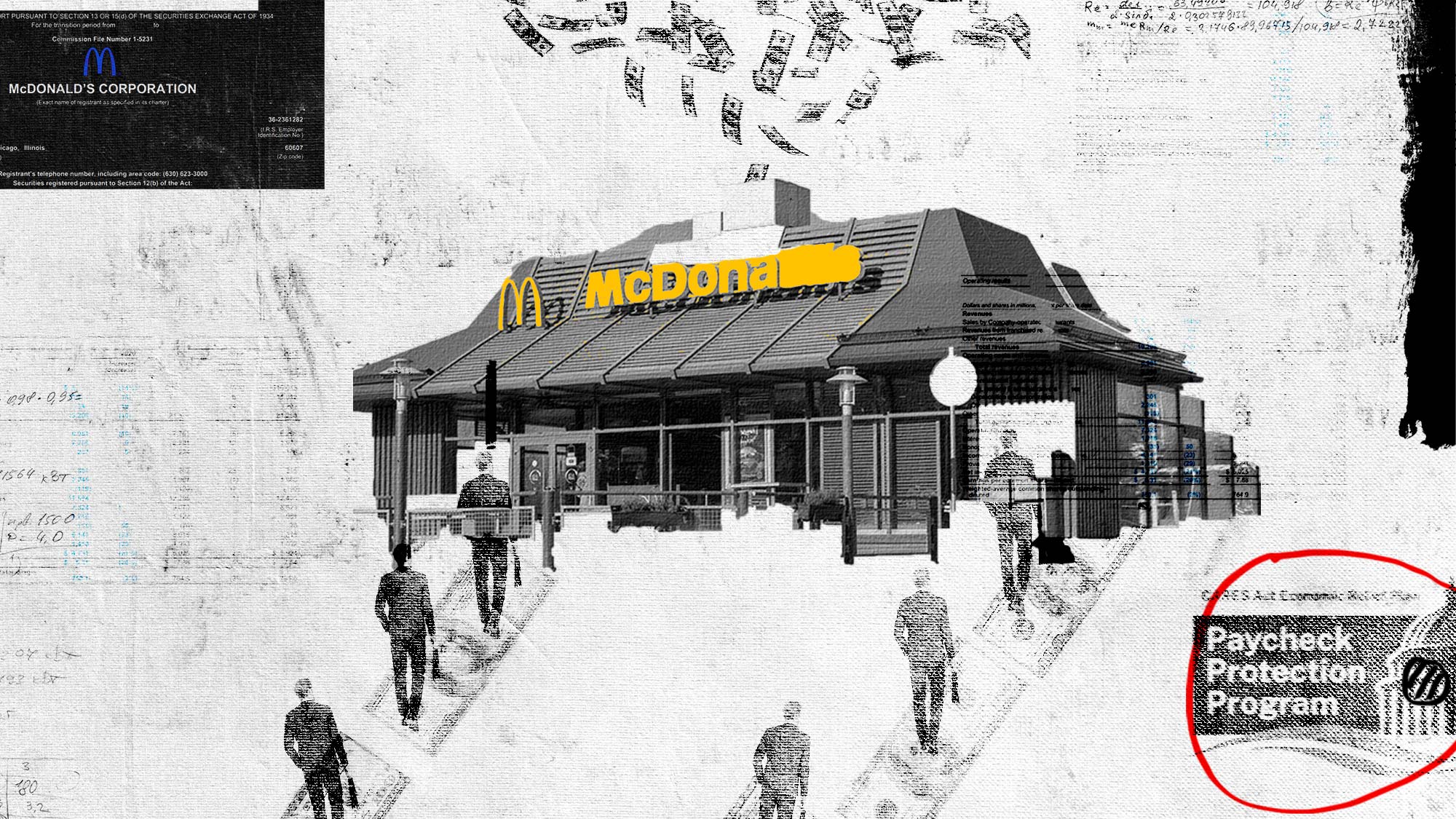

Graphic by Alex Hinton | Source Images: iStock, McDonald's 2020 Annual Report, sba.gov

The Covid relief loans were designed to keep workers employed, but fast-food franchises allocated money to their landlord, the McDonald’s corporate office.

In partnership with The Intercept.

At the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, McDonald’s franchisees asked the company for help weathering the coming storm. Specifically, the National Franchisee Leadership Alliance, a group that represents franchise owners, asked for something McDonald’s was well positioned to provide: rent relief.

Unlike many chain restaurants, McDonald’s leases or owns most of the land and buildings on which its U.S. franchises sit. One former executive estimates the corporate office is the landlord for 85 to 90 percent of its U.S. franchises. In 2019, the corporation collected $7.5 billion from franchises in rental payments across the globe, according to company filings, more than it collected in royalties and more than a third of what it reported in revenues across both the corporation and its franchises that year.

In the spring of 2020, McDonald’s refused to grant even a two-week rent forgiveness request. Franchises instead turned to the Paycheck Protection Program, or PPP: a federal Covid-19 relief program designed to help small businesses keep workers on payroll. A new analysis of loan application data by The Counter and The Intercept found that franchisees planned to use more than $31 million in taxpayer-backed PPP dollars on rent.

“It’s unfortunately wholly unsurprising,” said Lisa Gilbert, executive vice president of Public Citizen, a public interest organization, referring to the use of PPP funds for rent. “PPP had noble intentions and certainly was important in helping the country survive the pandemic. But it had many flaws, and systemic problems across the program have led to troubling outcomes.”

2,389 McDonald’s franchises collected approximately $1.3 billion in PPP dollars, according to data released in January by the Small Business Administration.

Groups representing the franchises claimed credit in aiding their members to get in on the PPP loans early, after McDonald’s corporate refused to grant rent relief. “[W]e helped prepare our Owners to be first in line, perhaps knowing the government, less solvent than our global company, was at least attempting to provide the desperately needed liquidity,” wrote Blake Casper, chair of the National Owners Association, another group representing McDonald’s franchisees, in a letter sent to company executives, on April 7, 2020.

PPP loans were in many ways an ideal solution for store owners. The program offered up to $10 million per franchise to pay for immediate expenses. And if business owners spent the money as Congress intended — mostly on payroll — then the loans were eligible for forgiveness.

In response to a March inquiry from The Counter and The Intercept, McDonald’s global communications manager Joseph LaPaille said that the company “never asked for assistance from any government entity.” While McDonald’s may not have requested direct Covid-19 relief, the analysis of PPP data shows it did collect federal dollars — in the form of rent checks funded by the taxpayer-backed small business program.

All told, 2,389 McDonald’s franchises collected approximately $1.3 billion in PPP dollars, according to data released in January by the Small Business Administration, or SBA, the agency that administers the program. That makes McDonald’s stores the second largest franchise recipient by total dollar amount. Only General Motors businesses, whose car dealerships are franchises, took in more total PPP dollars.

Of the loans to McDonald’s franchisees, 421 include rent figures, which totaled more than $31 million. The Counter and The Intercept attempted to reach the owners of each of these franchises. Two owners, who applied on behalf of multiple restaurants, confirmed that they used the loans as indicated: to pay a total of over $450,000 in rent to McDonald’s. Another said he wound up using all of the money on payroll costs instead. The vast majority declined to comment or did not respond to phone calls, emails, or fax messages. Those who agreed to speak with The Counter and The Intercept asked for anonymity, citing fear of corporate retaliation.

No solid spending data

The $31 million in rent payments is a substantial figure, but the actual amount may be higher, said Sean Moulton, a senior policy analyst at the Project on Government Oversight, an independent watchdog. That’s because the dollar amount breakdowns released by the government reflect only what was listed in borrowers’ loan applications — nonbinding estimates of how the money would be used. Around three in four franchisee applications showed plans to spend 100 percent of the funding on payroll costs, a trend Moulton said is consistent with application data for the program as a whole.

“It strikes me as unusual that, even in the early days, almost everyone was claiming, ‘It’s all going toward payroll,’” said Moulton. “As far as the lenders and the SBA were concerned, it was a nonissue if you were getting those fields wrong.”

The nonbinding spending estimates point at a key caveat to SBA’s data: It only reveals how borrowers intended to spend their PPP money. Loan forgiveness data would provide a more accurate reflection of actual spending breakdowns. However, in response to a Freedom of Information Act request from The Counter and The Intercept, the SBA said it does not collect specific category breakdowns from forgiveness applications, which lenders process and keep the records on.

With borrowers declining to specify how they used the money, it’s unclear precisely how many taxpayer dollars were ultimately paid to McDonald’s Corporation or its real estate affiliates in the form of rent. According to the SBA, individual lenders were responsible for collecting detailed forgiveness information. The Counter and The Intercept contacted 88 lenders who processed loans on behalf of McDonald’s franchisees, but none provided additional detail.

“We’ve gotten almost no information about what these companies are claiming, and it makes it impossible then for any kind of outside evaluation [of whether] the forgiveness makes sense.”

The lack of concrete data also makes it impossible to understand the impact of a relaxation of the rules, passed by Congress in June 2020, that allowed businesses to direct a greater percentage of the money — 40 percent instead of 25 percent — to nonpayroll expenses, including rent. The change came after most of the McDonald’s franchisee loan applications were filed. Franchise associations representing both McDonald’s and its franchisees were involved in lobbying efforts to loosen the restrictions.

“The PPP loan program was designed as a lifeline for small businesses, but the program’s limitations imposed by regulators were sinking them,” said Matt Haller, a senior vice president at the International Franchise Association, in a press release the week before the flexibility legislation passed.

McDonald’s initially responded to a set of general inquiries from The Counter and The Intercept but did not respond to a subsequent list of detailed questions and a final request for comment. A company spokesperson issued the following statement: “As the Paycheck Protection Program intended, some independent small business owner franchisees independently applied for and used PPP loans to support payroll for the continued employment of the nearly 800,000 local restaurant employees who work in McDonald’s-brand restaurants throughout the U.S.” The SBA did not respond to a list of questions and requests for comment.

“This is practically a black hole,” said Moulton, referring to PPP loan forgiveness data. “We’ve gotten almost no information about what these companies are claiming, and it makes it impossible then for any kind of outside evaluation [of whether] the forgiveness makes sense.”

A real estate empire

In the 1950s, when the McDonald’s real estate empire was born, the business model that put the young chain’s growth into hyperdrive was not a small cut of the burger sales. Instead, the parent company buys or leases the land on which its restaurants sit, then charges its franchisees a base rent plus additional rent based on a percentage of sales. At the end of 2020, McDonald’s Corporation held $37.9 billion in real estate assets before depreciation.

“McDonald’s is a real estate company,” said Marcia Chatelain, author of “Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America.” “It’s able to use the profits of McDonald’s, the hamburger company, to maintain an incredible portfolio of wealth in real estate.” Owning property, Chatelain said, has provided the company extra stability in times of crisis.

Yet in the spring of 2020, when the National Franchisee Leadership Alliance asked for the two-week rent forgiveness, McDonald’s refused.

“Owners were furious,” wrote one former McDonald’s executive familiar with the negotiations in an email. “They couldn’t believe the world’s largest restaurant company couldn’t give them some support … when you read about all the other smaller restaurant chains doing it every week.”

It’s possible, based on existing SBA data, that a significant portion of the taxpayer funds were simply used to support landlords and utility companies.

The company ultimately deferred — but did not forgive — the collection of $490 million in rental income, plus nearly half a billion dollars in royalty payments. The company’s business filings later revealed it recouped more than 80 percent of deferrals by the end of 2020 and was on track to collect the rest in 2021. Despite pandemic-related instability, McDonald’s collected $6.8 billion in rent payments in 2020.

McDonald’s is likely not the only corporation that collected taxpayer dollars in the form of PPP rent payments. Other fast-food chains like Wendy’s and Restaurant Brands International — parent company to Burger King and Tim Hortons — own franchise real estate, though their rental revenues are a fraction of McDonald’s.

If the arrangement of having megacorporations collect federal aid money bears further scrutiny, it’s not likely to come from the Small Business Administration.

To run the massive $789 billion program, the SBA offloaded the administrative task of processing PPP paperwork to lenders, like private banks and credit unions. As a result, the agency said it doesn’t have forgiveness records related to any particular PPP loan.

The lack of transparency surrounding PPP forgiveness data raises key questions about whether or not the program actually achieved its core aim: keeping workers on payroll. Left unanswered, it’s possible, based on existing SBA data, that a significant portion of the taxpayer funds were simply used to support landlords and utility companies.

“The stated purpose of this program from the beginning was to try and preserve jobs,” Moulton said. “It’s the name of the program. The more you dilute that with the authorization to use it on rent or mortgage payments or utilities, it really dilutes its impact.”

“Did we save jobs?” he said. “We spent a lot of money, and it’s very hard to answer that very simple question.”

Questions about how McDonald’s was able to bounce back from the early days of the pandemic are easier to answer. In January, the company’s chief executive called 2021 a “banner year” for the company, despite the public health crisis. The McDonald’s corporation reported $23.2 billion in revenue worldwide — its highest total since 2016.