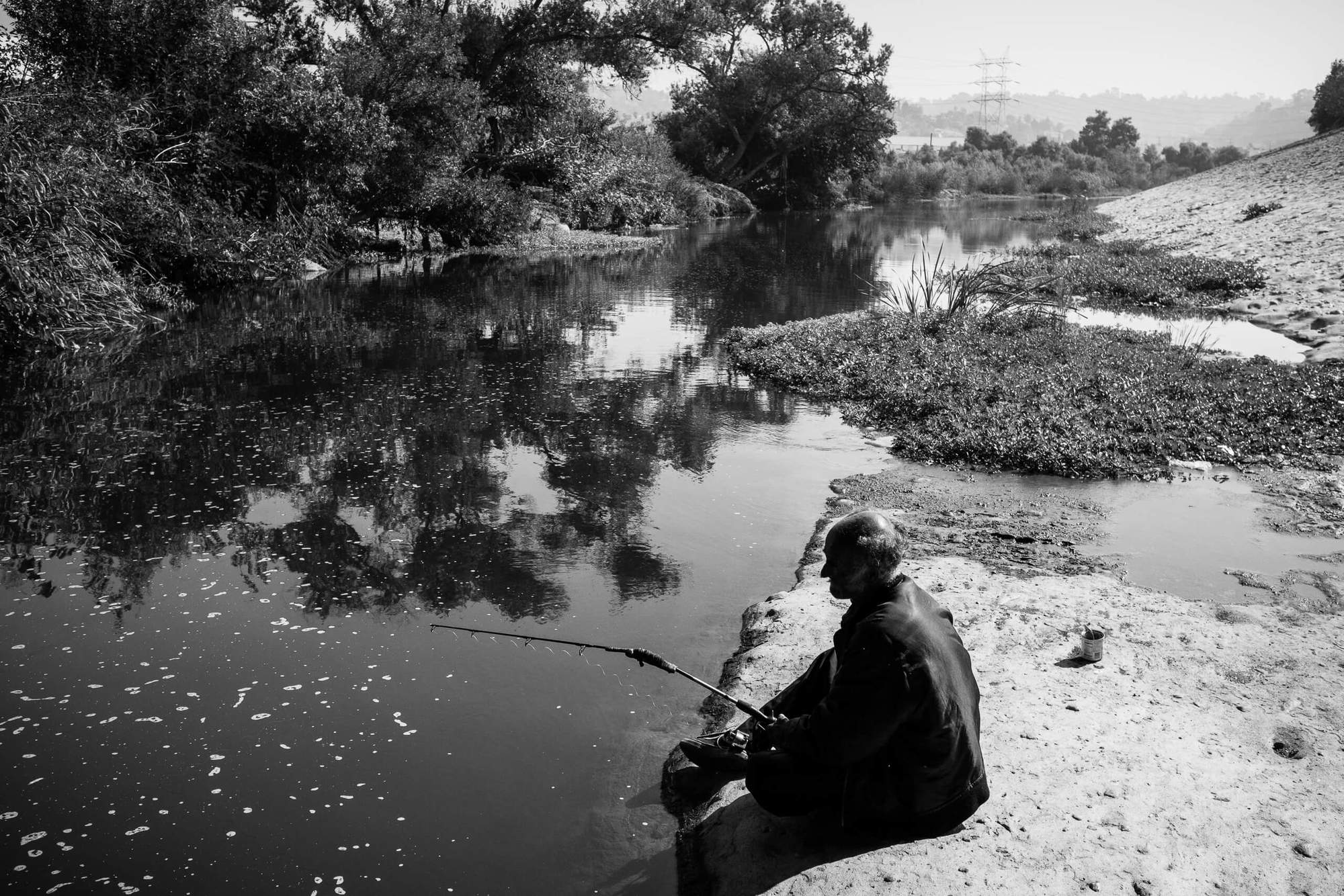

Photo by Roberto (Bear) Guerra

Unhoused Angelenos use the urban river as a source of sustenance, but a proposal to revitalize the waterway could push them out.

On a March afternoon on the Los Angeles River, two anglers waded in the concrete channel of the Glendale Narrows, casting their lines for carp and largemouth bass. Above them, a belted kingfisher perched on a mattress that had been caught in the crook of a budding cottonwood during a recent storm surge. Some recreationists enjoy catch-and-release on the river, but others — low-income and unhoused people who need sustenance — were hoping to leave with coolers, buckets or even shopping carts full of freshly caught fish.

This story was originally published at High Country News (hcn.org) on April 20, 2021. Photography by Roberto “Bear” Guerra, photo editor at High Country News.

Pictured above: Samuel (last name not given), an unhoused resident of the LA River, fishes for a meal under a freeway bridge near “Frogtown,” a river-adjacent neighborhood that has seen a steep rise in property values in recent years.

For over 10,000 years, the Los Angeles River — known to the local Gabrieliño-Tongva tribe as Paayme Paxaayt — has provided food, water and a way of life to residents of the Los Angeles Basin. Steelhead trout once spawned in its headwaters and helped feed the numerous villages along its course. But since 1938, the 51-mile river has been bound in concrete. Now, many worry that its fish aren’t safe to consume, a stigma that has long loomed over angling here.

“Most tend to think the quality of the water in the Los Angeles River is poor, but it’s fairly clean water,” says Sabrina Drill, natural resources advisor for the University of California Cooperative Extension. While toxicity varies by species and location on the river, a 2019 LA River report found that a person can safely consume 8 ounces of common carp, bluegill, and green sunfish, up to three times per week. Still, Drill did not recommend this, since most of the studies contained small samples.

The Los Angeles River is reflected under a freeway overpass, while, in the background, willow trees grow on an island in the soft-bottom stretch known as the Glendale Narrows.

Photo by Roberto (Bear) Guerra

Yet many unhoused and other low-income Angelenos — over a thousand people a year, according to some experts — supplement their diets with the urban river’s fish and crustaceans. Nearly 9,000 of the estimated 66,000 unhoused people in Los Angeles County live along the river, where they’ve set up camps and shelters — even small gardens with fruit trees, bushes and terraced agriculture, hidden off its concrete banks.

Their future, however, has become even more tenuous with the recent draft of the LA River Master Plan, a massive proposal to revitalize portions of the river with pavilions, cultural centers and multimillion-dollar parks. The plan — developed by a committee of nonprofit organizations, municipalities and governmental entities, assisted by public comment — will be released later this year. But already advocates have raised concerns, and groups like the Eastyard Center for Environmental Justice are worried about the prospect of “green gentrification,” which occurs when housing prices rise after parks are built in historically marginalized communities.

The draft plan’s environmental impact report suggests that many homeless encampments are likely to be removed during construction, and that law enforcement patrols will increase to prevent new ones from forming. The plan offers no housing solutions for the thousands of people currently living on the river.

“You have economic revitalization and park construction prioritized over people’s ability to live and survive.”

Homeless advocates worry that those who will be most heavily impacted by the plan had no chance to comment, since many who live on the river lack reliable access to the internet or are unable to attend public meetings. “What’s happening on the Los Angeles River is a humanitarian crisis,” says Jason Post, who has been studying the river for six years. “The reality and experiences of LA River anglers and of people who, on the day-to-day, live in and along the river are not reflected in the master plan. You have economic revitalization and park construction prioritized over people’s ability to live and survive.”

What we know about the river’s modern community is limited, but its members are part of a long history of invisible Angelenos who have lived and fished along the riverbanks for more than a century, both before and after channelization. In “Unnatural Nature,” a study published in the December 2020 Geographical Review, Post and co-author Perry Carter examined how anglers have reimagined and repurposed this far-from-pristine space as parkland and urban wilderness.

Their study, which noted the inequities in the park-poor city of Los Angeles, showed how the river provides refuge, food and shelter for some anglers and unhoused people. None of the 23 sustenance anglers I spoke with in the three months I reported on this story wished to speak on the record. Many couldn’t afford fishing licenses and so were operating outside of the law; others said they had been harassed by law enforcement. In the past, anglers and unhoused Angelenos have been given loitering tickets while on the river. Others feared encampment sweeps.

José Carlos (last name not given), an immigrant from Guatemala who has lived here for more than 10 years, walks down the bank to the river to bathe.

Photo by Roberto (Bear) Guerra

Carolina Hernandez, the Los Angeles County Public Works principal engineer and spokesperson for the LA River Master Plan, says that while the plan doesn’t specifically address fishing or sustenance fishing on the river, it does prioritize healthy ecosystems that allow angling. Social justice and environmental groups were on the plan’s subcommittee, but no homeless advocacy groups were involved, and very few unhoused residents attended meetings. “There was not a direct survey of our unhoused community in the LA River Master Plan,” Hernandez told me. The plan is a road map, she added, one that shouldn’t supersede specific project engagement.

Recently, in Glendale Narrows, I saw how intimately those experiencing homelessness interacted with the river. One woman washed her clothes in the current as her cat watched a stand of black-necked stilts feeding in the shallows. In the distance, three men played darts on a sandbar island, their tents lined up below a large cottonwood. Another man sat patiently nearby with his tenkara rod cast in the flow. Beside him, a small red cooler held a medium-sized carp.

One unhoused resident I met near an encampment farther upriver told me he’s lived along the waterway for over a decade, constantly moving his camp up and down the river to stay hidden. The man, who is in his mid-40s, told me he bathes in the river, eats carp from it, and currently sleeps at the mouth of a storm drainage. “I don’t know where I would go if (the master plan) swept me away from my home,” he said. “The river keeps me alive.”