Graphic by Tricia Vuong | Flickr/Alaina Browne

How does Black food go viral among white folks?

Historian Rachel Martin grew up in Nashville, Tennessee, without ever learning about—or eating—her city’s iconic dish, hot chicken.

It’s a deceptively minor point in her book, Hot, Hot Chicken: A Nashville Story, which explores Music City history through this dish and the undeniably racist “urban renewal” policies that gutted her hometown’s Black neighborhoods. Still, it’s a point to which I kept returning. I wondered: How could she not have known this delicacy created within miles of her home, or its roots in a legendary lovers’ spat? Suffice it to say the answer lies in persistent racial, spatial, and culinary segregation, which kept hot chicken in Black Nashville for years—and the author and her family in white Nashville until her adulthood.

Vanderbilt University Press

As the hot-chicken origin story goes, infidelity is the mother of invention. Sometime, probably around the 1930s, pretty-man Thornton Prince III’s wandering eye led indirectly to this gastronomic breakthrough. Thornton incensed his lover after staying out all night. The woman-at-home suspected he’d been gallivanting with another woman and prepared a hearty breakfast of blistering-peppery fried chicken, designed to punish his palate and make a point. Thornton was apparently oblivious to her heartache and heartburn, but loved the chicken. He saw a marquee menu item for his “chicken shack.” And so that act of “he-won’t-do-right” cooking planted the seeds for his family’s modern business, now known as Prince’s Hot Chicken.

What began as local love-hate on a plate has become a national phenomenon. The family-owned restaurant won a coveted James Beard Foundation America’s Classic award in 2013. This hyperlocal specialty has spawned countless imitators, from fast-food chains—KFC came to Nashville for “inspiration” —to food trucks and restaurants nationwide. A particularly bourgeois version is currently enticing New Yorkers to wait up to eight weeks for a $35 three-piece (laced with peppercorns and accompanied by almond-pesto sweet potatoes). You can even buy hot-chicken pizza, heavy on the pickles and drizzled with sriracha.

How did Prince’s hot chicken become a trendsetter? And, more generally, how do Black culinary novelties leap into white consciousness? Of course, there’s no one-size-fits-all answer; region, mode of creation, historical period, market trends, and access to capital all factor in. And goals do, too. Not every Black food innovator starts in the same place or aims to serve the same population (and may not indeed aim to specifically serve Black audiences). And access to white markets doesn’t ensure commercial success.

Is it possible to have Black culinary crossover without appropriation, in a country built on stolen Black labor?

Martin’s account is equal parts mystery, policy explainer, and entertaining business and food history. But hot chicken, as told through Martin’s book, pushed me to think about how Black food migrates into white communities, a larger cultural process that the book leaves too implicit until its later chapters. That process includes multiple ways a food is racialized, consumed, commercialized, rendered fashionable, and ultimately co-optable. Black food innovations spread first inside African-American communities, before gradually penetrating layers of racial segregation—past or present—to register with successive generations of white diners.

Their changing palates can be a boon or burden for the Black culinary creative. After all, white America has an insatiable appetite for Black “cool,” the seemingly effortless capacity of Black people to create distinctive aesthetics and the ineffable, be it in fashion, music, hairstyles, or food. Yes, white appreciation can translate into respectful consumption, the kind that self-consciously references Black originators. But that admiration and emulation can quickly devolve into something much more extractive.

I ask myself, and this is no trivial question: Is it possible to have Black culinary crossover without appropriation, in a country built on stolen Black labor? Because, in America, Black innovations are too often translated into crass or soulless reproductions (think Kardashiana), monetized by white culture for white culture. It’s an established pattern, one that hot chicken exemplifies: There’s a slide toward de-racialization, and the erasure of the dish’s Black roots, until the average eater has little idea that their hot-chicken tenders came from anywhere other than the joint that sells them.

Dave’s Hot Chicken has sold 300 franchises for what it describes as Nashville-style “street food” since it opened in East Hollywood, Los Angeles, in 2017.

Take, for example, Dave’s Hot Chicken, which has sold 300 franchises since it opened in East Hollywood, Los Angeles, in 2017. As Dave’s—co-founded by a chef trained in Thomas Keller’s “Bouchon organization,” according to the company’s website—describes its origin story, “four childhood friends came up with a simple concept—take Nashville Hot Chicken and make it better than anyone else in America.”

What a poor yet revealing choice of words. “Take” hot chicken and improve its soul-food insufficiency with “chefly” knowhow. The website mentions its “proprietary brine,” but not the Prince family, which now owns two locations.

The Princes have something else as well: a legion of non-Black business descendants who rarely acknowledge their pioneering and ongoing work. Some shout-out the Princes in homages that cost newbie hot-chicken entrepreneurs nothing and imply a sort of creative kinship that’s utterly lacking in this wholesale hijacking of hot chicken.

How chicken got hot

Chicken; a spicy, savory rub (wet or dry); pickles; and that tabula rasa of carbohydrates, white bread: One can argue that’s too general to constitute intellectual property. What makes a concept—not a recipe with defined quantities of ingredients and delineated cooking methods—ownable?

I’m not sure—and I’m not sure I’ll ever be sure. But culinary authorship—and who’s responsible for a dish’s popularization—counts.

Long before hot chicken set anyone’s lips afire, the domesticated chicken was linked to Black Americans. As scholar Psyche Williams-Forson wrote in Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power, free and enslaved people were often the “primary chicken vendors” of their antebellum communities, despite laws that prohibited trading by and with slaves. Hocking poultry gave enslaved women a measure of economic autonomy, if not freedom. That preponderance of Black chicken sellers before the Civil War likely influenced much nastier associations, the enduring stereotypes that Black people would do anything—steal, tap dance, or abandon all common sense—for chicken, preferably fried.

So decades before Thornton got that wee-hours tongue burn, hot chicken’s saga had already begun. Hot chicken had a historical head start in its designation as Black food, simply because it was chicken. The spicy, peppery delight made by the original angry woman became triply Black: created in a Black home in a segregated neighborhood; prepared in a growing number of Black restaurants in Nashville; and consumed in Black homes for decades.

Prince’s Hot Chicken served X-tra hot with mashed potatoes and cole slaw.

Photo by Alan Poizner/For The Washington Post via Getty Images

Hot chicken started as many innovations do: in a burst of domestic creation—and, as often happens in Black history, by a person who can’t be fully credited. On one hand, the Princes’ hot chicken can be traced with remarkable precision (unlike other soul food dishes with fuzzier and disputed origins, such as chicken and waffles). On the other hand, the name of the angry woman behind that first incinerating batch has been lost to time. In Hot, Hot Chicken, Martin gamely tries to identify her using all the archival materials and historian’s tricks at her disposal. But because Thornton Prince III was a serial groom with an itinerant phallus and outside children, he left a cortege of pissed-off contenders for the crown. Was it first wife Gertrude or Mattie, with whom he had a child during his marriage to Gertrude?

Though this woman’s namelessness seems to be a function of time and a shattered relationship (if we believe the narrative), that’s not the only explanation for her absence.

Chasing historical leads and dead ends, Martin helps readers see invisible hands at work: the urban planning that made today’s Nashville into a booming, still-segregated metropolis, and the Black women and men who established an enduring food tradition. The American food economy has long hidden or pooh-poohed the contributions of important laborers, even as it’s relied on them for profit: the enslaved cook; the Black domestic in freedom; the unnamed Black chef behind Bisquick mix; the immigrant; the mother who makes meals; the woman whose home-based work isn’t separate from wage-earning activities. It’s largely erased countless figures like John Young, the man whose mumbo or mambo chicken sauce paved the way for another hot, saucy chicken dish: Buffalo wings.

At some point, Nashville’s hot and saucy chicken ceased to be a family meal or a secret. Maybe Thornton Prince, apparently once a hog farmer, decided to raise more chickens. Maybe he started selling takeout hot chicken from his back porch. But someone decided this chicken was saleable, and many other someones agreed it was worth buying. Hot chicken became intraculturally popular in Black Nashville. That community sustained Prince’s and also birthed local Black competitors who recognized a hot thing and business model when they ate it or made it (because a few former Prince’s employees have started businesses with their own versions of hot chicken).

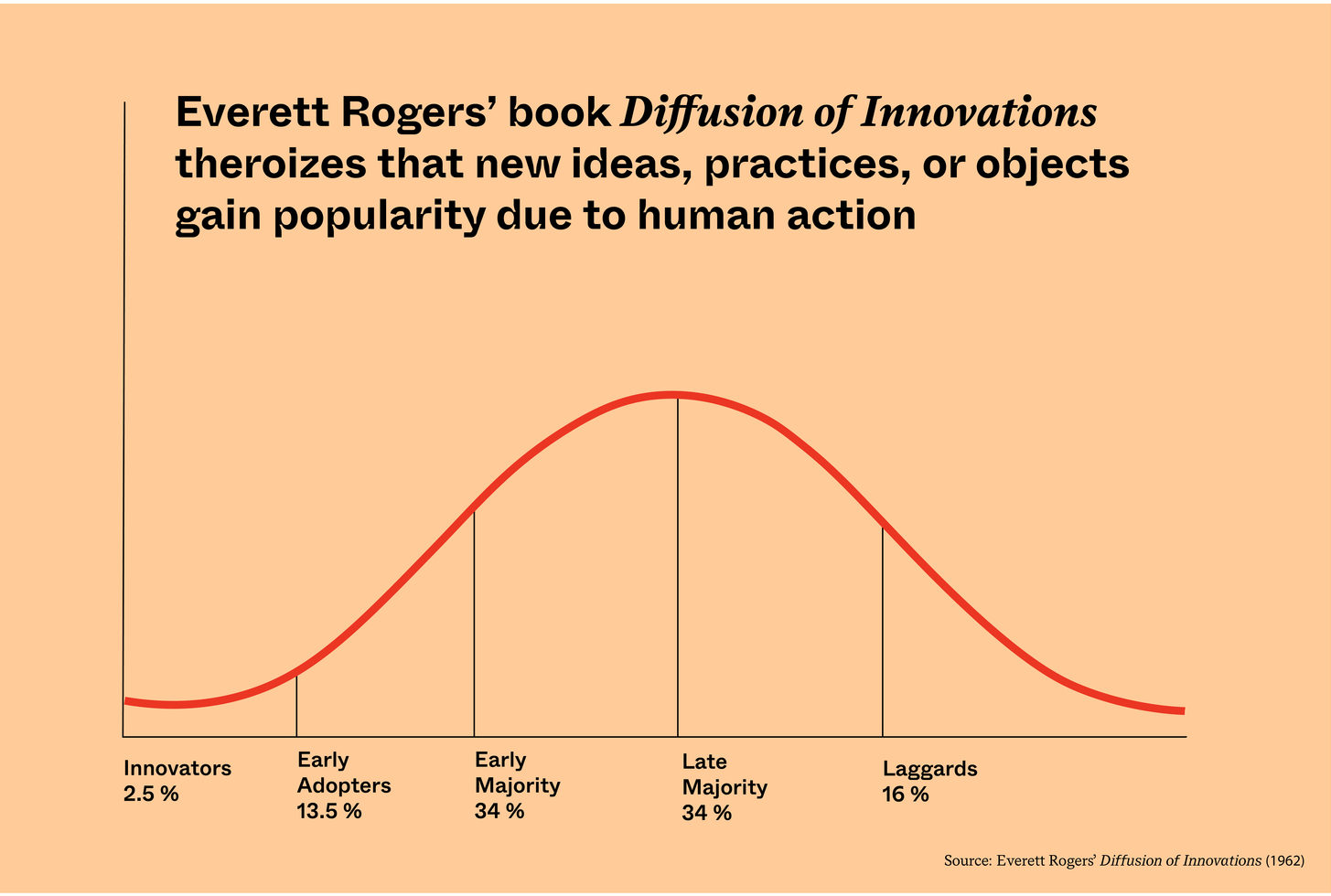

The originators of hot chicken and their customers were what communications scholar Everett Rogers called “innovators” and “early adopters” in his 1962 book Diffusion of Innovations. He categorized people by how fast they embrace new ideas or products. In his much revised and debated theory, 2.5 percent of people are “innovators,” the risk takers. They’re followed by “early adopters” who catch on quickly, thrive on novelty, and ply their influence. The masses—estimated to be nearly 70 percent of a given network—are the “early and late majorities” who wait to embrace newfangled thingamajigs. The “laggards” bring up the rear, resistant or slow to change. A person can innovate in one sphere and lag in another part of their life, and many factors influence an individual’s engagement with an unfamiliar concept: whether the idea or product seems advantageous, is easy to learn, can be tried before adopting it, and whether it fits into an existing belief system.

Talia A. Moore

All that sounds neutral and perfectly reasonable—and absolutely raceless. In Rogers’ theory-speak, Thornton Prince III and his great-niece, André Prince Jeffries (who runs the business today), would be the innovators. Those who’ve recently discovered the Princes’ fabled hot chicken—much of white and middle America—are laggards. But Rogers’ original research, which investigated why farmers hesitate to use new technology that could boost their yields and bottom lines, didn’t explore the way racial dynamics can complicate habits of adoption. “Existing belief systems” also include racism, Jim Crow, and lasting disparities in access to material and social capital—and those factors help to explain both hot chicken’s deep community roots and its seemingly sudden, mass-market virality.

Given this country’s rapacious harnessing of Black cultural production, Rogers’ theory needs a significant tweak. When it comes to hot chicken and other Black innovations, some white laggards eventually see opportunity. And not only do they accelerate adoption of something that is foreign to them, they claim it as their own in an act of material and narrative gentrification. The way they tell it, they were the innovators all along.

“You’re gonna talk about this chicken”

Let’s pause for a moment here: There can be a beautiful inaccessibility to Black culture, things that white and non-Black people do not know or cannot fully grasp even if they’re momentarily “invited to the cookout.” That inaccessibility—and segregation past and present—helps the laggard convince himself he’s an innovator.

Nashville hot chicken was created in an environment where racial cultural divisions were made all the more stark by physical and structural barriers such as Black people’s unequal access to desirable real estate or bank loans. Martin exhaustively recounts how its genesis dovetails with the rise of a Jim Crow innovation in her city: urban renewal policies that declared Black areas to be unlivable “D” zones in need of “redevelopment.” Among many changes, the “beautification” of Nashville cleared the mostly-Black area near the Capitol and made way for not one but three highways that bisected Black neighborhoods. Streets were dead-ended, businesses closed, children and families cut off from their playgrounds and walking routes.

Nashville’s spatial and cultural segregation contained hot chicken to Black neighborhoods where upper-crust whites rarely tread. Segregation had its unintended benefits, giving Black communities the freedom to create and Black businesses a stream of culturally consonant consumers barred from boundless shopping in white retail spaces. It could also inhibit growth, though, limiting access to the white market or forcing Black businesses to relocate according to the whims of white urban planners.

Everett Rogers’ diffusion theory would have seen the late-night eaters, those country-music stars hungry after a gig, as the early majority. They preceded “proper” white taste makers, another stage in my theory of Black food diffusion.

But communities aren’t hermetically sealed, even and especially in the segregated South. Black and white Southerners have always lived together or near one another, regardless of segregationists’ Herculean efforts to craft a divided world. Their own laws proved how futile their efforts were, and that Jim Crow was powerful but not omnipotent. The era’s obsessively detailed lawmaking reveals just how often racial boundaries were breached; in 1930, Birmingham, Alabama, banned whites and Blacks from playing cards, dice, or checkers with each other—a frantic attempt at legislating against interracial interaction that was already occurring.

André Prince Jeffries, great-niece of Thornton Prince III, runs Prince’s Hot Chicken today.

It was only a matter of time before a greater share of white Nashville got wind of the chicken. Everett Rogers’ diffusion theory would have seen the late-night eaters, those country-music stars hungry after a gig, as the early majority. They preceded “proper” white taste makers, another stage in my theory of Black food diffusion. Late to the game, these conventional influencers are few enough and sometimes powerful enough that no restaurant is going to serve them side-eye.

In the case of hot chicken, former Nashville mayor Bill Purcell started patronizing Prince’s and became an evangelist. According to Martin, he often conducted political lunches over its plates, telling André Prince Jefferies (who invented Prince’s spice scale of mild to will-almost-take-you-out) to serve his lunch dates the most scorching—no matter what spice level they ordered. That element of palate surprise meant he’d always have a laugh and the upper hand. A journalist who endured this nonconsensual trial by chicken said, “After three bites I figured out he didn’t ask reporters to lunch because he liked them. He was trying to kill us off, one by one.” Like that woman who gave Prince’s its famous recipe, Purcell believed in the sneak attack.

Prince’s Hot Chicken carved out a territory of its own: generations of faithful Black customers and competitors, a new privileged class of eaters, admirers and usurpers, national awards, hot chicken festivals, and popups sprouting willy-nilly. Chalk that down to hard work, creativity, the Southern jones for chicken, and as André Prince Jeffries told Martin, “This chicken is not boring. You’re gonna talk about this chicken.” Not every edible product regularly provokes a response, much less sweat, nose drippings, and tears of joy or pain.

To eat hot chicken isn’t merely an act of consumption. It can refute the reputation for white blandness, prove that the white eater is in the know, and provide some superficial entrée into Black culture.

External factors—such as Americans’ foray into spicier foods—also helped propel hot chicken to its Moment. Heat-heads have flocked to the Fiery Foods Festival since 1987. Salsa has long surpassed ketchup in our national favor. Even salsa seems, well, milquetoast compared to the potent and piquant condiments making frequent appearances in previously blah food mag recipes. The pendulum of spice preference and fashion has swung to the point that a March New York Times article presumed that spice-love is approaching cultural norm status, and deviance from it may prompt shaming and taunts; it advised readers who “can’t take the heat” that a “taste for spicy foods can be learned” or at least tolerated if you want to fit in.

That flavor recalibration—as Americans get hip to foods that have always been here but are often associated with our immigrant neighbors—is close cousin to an important “flava” transformation vis-à-vis Blackness. To eat hot chicken isn’t merely an act of consumption. It can refute the reputation for white blandness, prove that the white eater is in the know, and provide some superficial entrée into Black culture.

The acquisition of Black cool, perhaps the most critical stage for this humble yardbird’s spread, fuels American popular culture. From there, it can be a rush toward enhanced profitability or expansion. Maybe that arrives in the offer to franchise or to package that spice blend. It almost inevitably comes with another cycle of friendly and hostile competitors.

That success—where everybody knows your name and everybody wants your secret sauce—comes with increasingly loud whispers of appropriation. But in a country based on Black stolen labor, it’s on message to demur that a particular preparation of chicken, pepper, salt, pickles, and white bread is a pleasing combination of ingredients. And that it belongs to no one.

In fact, this insistence may be the final stage of appropriation—and it’s the American way. African-American food is always up for grabs. I think of it as the worst form of takeout, really. And few people want a side of history with their meal.