Romantic ideas about locally grown food and a lack of statewide planning could be getting in the way of making real progress addressing food insecurity, climate change, and the economy.

Double food production in Hawaii. Triple the percentage of locally grown food consumed in the state. Make state agencies source at least half their food locally.

This story was published with permission from Honolulu Civil Beat.

Honolulu Civil Beat

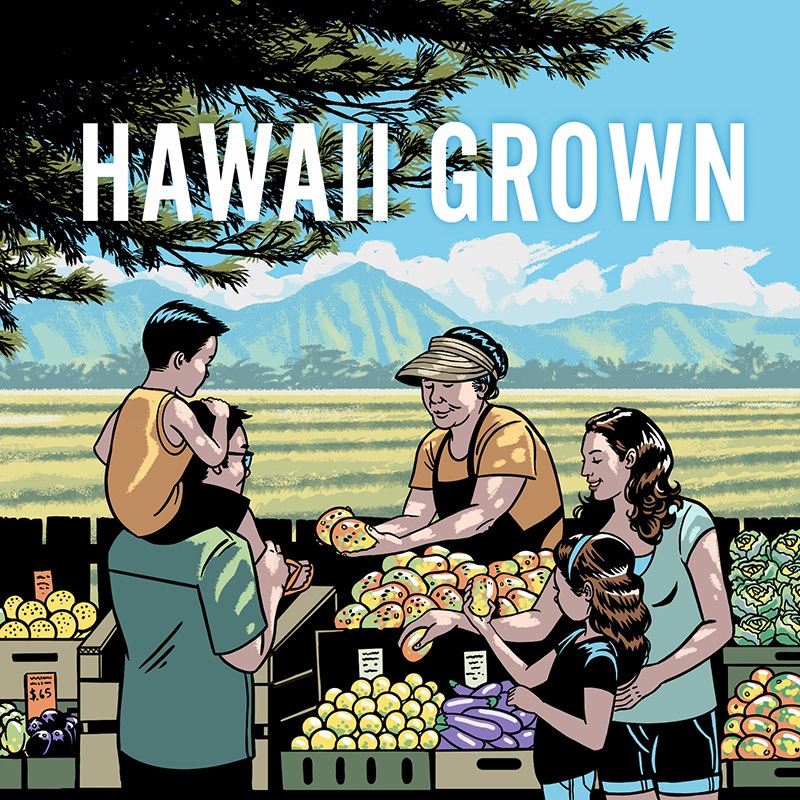

“Hawaii Grown” is funded in part by grants from the Ulupono Fund at the Hawaii Community Foundation, the Marisla Fund at the Hawaii Community Foundation, and the Frost Family Foundation.

Hawaii has some very ambitious goals for revitalizing the state’s languishing agricultural sector—a desire that has only been intensified by the food shortage scares and supply chain disruptions that have accompanied the coronavirus pandemic.

Meeting any of the state’s production goals would be an enormous achievement. But there’s no comprehensive plan for how the state will get there—or even a clear idea of what a goal like doubling food production will accomplish.

That’s a problem, agricultural experts in the state say.

“We have this kind of fixation or this fetish around agriculture,” said Albie Miles, an assistant professor of sustainable community food systems at the University of Hawaii West Oahu. “But we need to be intellectual about this.”

Part of our collective fixation on locally grown food comes from a desire to get back to the land and have a deeper connection to the food that nourishes us, Miles said. But while those desires are valid and important, they can often muddy what we think farming can accomplish.

“The governor says we’re going to double local food production, but it was framed as ‘that’s how we’re going to build food security in the state,’ and it’s like, no. No, we’re not,” Miles said. Agriculture alone is not going to achieve food security. “Food security is an economic issue.”

Agricultural experts in Hawaii are beginning to ask: What are we trying to do? They say we need to rethink the state’s food security definition to be more realistic.

Cory Lum/Civil Beat/2020

What, then, are we trying to do? Do we want to grow more local food to cut down on greenhouse gas emissions and climate change? To keep economic dollars in Hawaii? To make fresh food more affordable to struggling families? To address obesity and public health concerns? To make the state less reliant on imports?

The answers to these questions should be guiding our goals for farming in Hawaii.

There are a lot of different reasons that people want to see agriculture preserved and expanded in Hawaii. Some of it is lifestyle and landscape.

No one wants to see the entire central valley of Maui urbanized, said Noa Kekuewa Lincoln, a professor of Indigenous Crops and Cropping Systems at the University of Hawaii Manoa. There’s a cultural component, a climate resilience component and an economic resilience component, Lincoln said. Hawaii has frequent discussions about these issues, but the conversation always seems to focus on one problem at a time.

“We don’t have a plan that really considers all of these things, how they get there,” Lincoln said. “And how they can support each other. How multiple outcomes could be realized through the same action.”

Creating a state food charter

In the last decade, stakeholders in a growing number of states have been addressing some of these questions by developing a state food system plan, a document that lays out state goals and guides policy decisions.

There are currently 18 states with an active food system plan or charter, and many more working to develop one, according to a survey by the University of Michigan.

A food system plan or charter sets a vision for food in the state. That means not only agriculture and food production but farmers’ markets and food procurement and programs like Da Bux that help low-income families access food. That vision can then help guide public policy and investment toward achieving specific goals, Miles said.

A growing number of states have been developing a state food system plan, a document that lays out state goals and guides policy decisions.

What Hawaii has had in the past is agricultural plans that single out food production from other parts of the food system.

“We could achieve doubling food production, but it’s not going to solve these other aspects of the food system that we need to simultaneously address,” Miles said.

These more comprehensive plans are in line with a broader trend at top-tier universities and think tanks to approach issues in a multidisciplinary way, Lincoln said.

Food system plans or charters can be based on a government-commissioned survey of state needs, but they often start as a grassroots effort that brings together an array of stakeholders to talk about big challenges and goals in a given area, said Lesli Hoey, an associate professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Michigan.

One thing that the charter process accomplished in Michigan was to really mobilize people, Hoey said, and generate support for people and groups with fledgling ideas that might not have otherwise gotten off the ground or had a big impact.

That need for support is one of the reasons it’s critical to involve lawmakers and state agencies in the process.

Miles is helping to lead a grassroots effort in Hawaii to start the process of developing a participatory food system plan, through an initiative called Transforming Hawaii’s Food System Together. He has also been working to drum up support for creating a food system plan with state lawmakers and private groups.

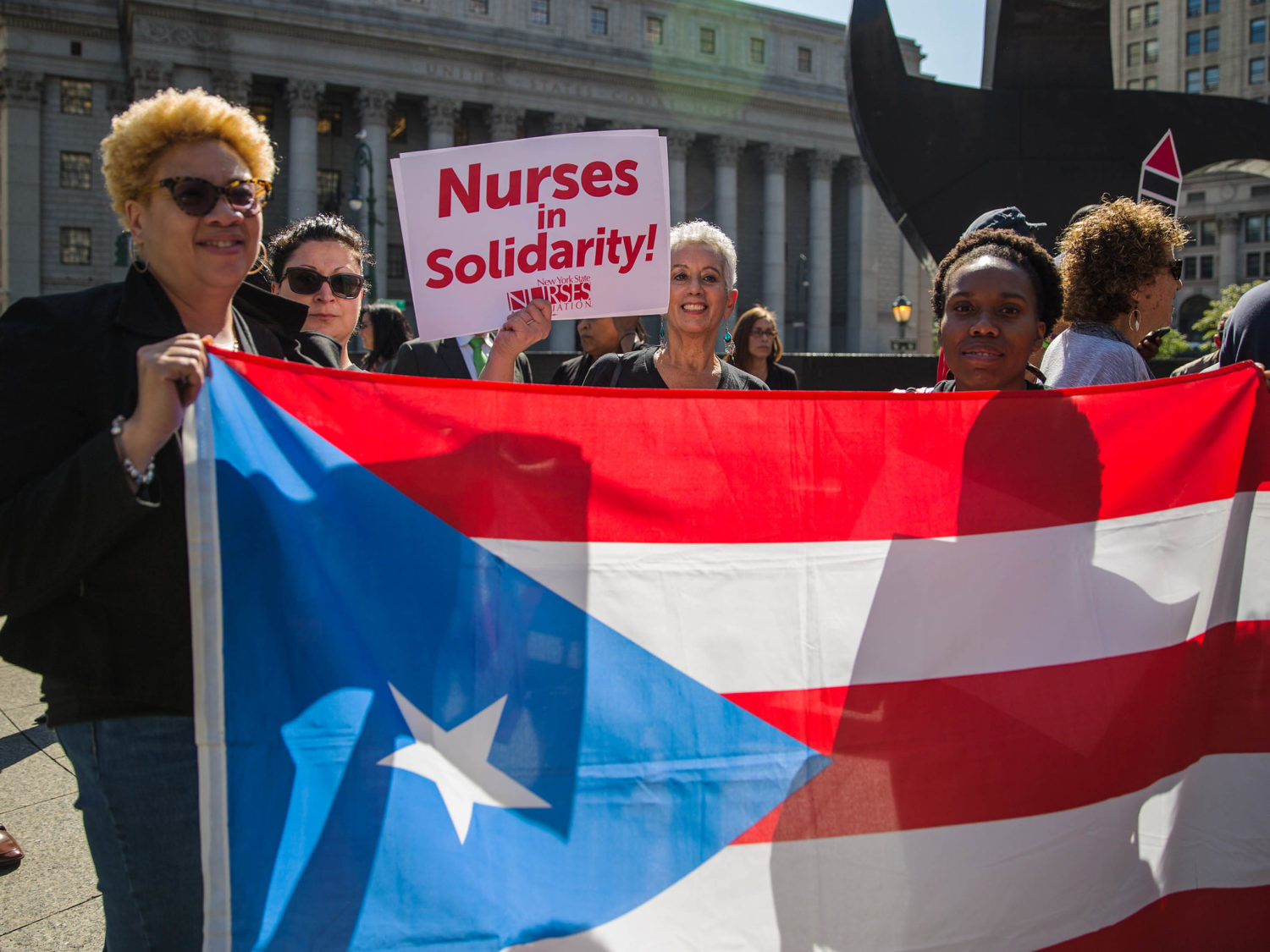

Hawaii needs a statewide comprehensive plan for food security that involves lawmakers as well as farmers and takes into consideration numerous economic, agricultural and social parameters.

Anthony Quintano/Civil Beat/2018

Other nonprofits and coalitions like The Ag Hui are also trying to bring people together for more coordinated conversations about needs in the state, Lincoln said. But these efforts are trying to fill a void in state leadership that shouldn’t be there.

“We’re not seeing leadership from our leaders. And so others are stepping up, but they don’t have the keys to the power as it were, to instigate those changes,” Lincoln said.

A lack of coordination

Bringing together stakeholders to create a roadmap for Hawaii’s food system is just one way to address a serious lack of planning and coordination when it comes to the state’s struggling agricultural sector.

“What we should be doing is asking ourselves, how well is the state providing services to farmers?” said University of Hawaii economist Sumner La Croix. “Why is it that farmers are not making money in the state of Hawaii, as most of them are not? What can we do to reduce the regulatory burden on farmers to make it less costly to produce food here in the state?”

If Hawaii had a better idea of what food it wanted to see grown to meet sustainability or food security goals, it could also use that information to create incentives for certain types of crops.

No one can tell farmers what to grow, said Nicholas Comerford, dean of the University of Hawaii’s College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources. They will grow what they know how to grow, what their parents grew, and what they think will make money.

But Hawaii needs a different kind of agriculture, he said.

“It needs it because we’re so remote, right?” Comerford said. “We need a better perspective on what the state needs to grow. And we have to provide the farmer with [information about] where it can grow, and what the economics of growing it are.”

The agriculture department has a list of crops that are most sought after in the state and are most nutritious. University of Hawaii has a detailed map of what crops grow best in the state. If that data could be paired with economic projections for what crops will be most profitable, farmers could then make more sophisticated decisions about what to plant.

If the state had a better idea of what food it wanted to see grown to meet sustainability or food security goals, it could also use that information to create incentives for certain types of crops.

“We need a better perspective on what the state needs to grow. And we have to provide the farmer with information about where it can grow, and what the economics of growing it are.”

Another way to help would be to bolster planning and coordination at the university system, said Bruce Mathews, dean of the College of Agriculture, Forestry and Natural Resource Management and a professor of soil science at University of Hawaii Hilo.

The university system has lost funding for a number of positions because agriculture hasn’t been prioritized in the state in recent decades, Mathews said. This means that there’s a lot of missed opportunities just within the university, Mathews said.

One idea would be to have a vice president for agriculture in the UH system who could coordinate all the agriculture departments and programs across the system in addressing big state challenges.

Some of that work used to be done by the now-defunct Governor’s Agricultural Coordinating Committee. The committee, which was eliminated more than two decades ago, was allotted a certain amount of state money each year to address priority problems, Mathews said. Then the committee would get faculty from across the UH system to meet with producers to identify challenges and submit proposals to address them.

“I mean, somehow you have to have all the ships in the Navy aligned to do what the Navy’s got to do,” Mathews said. “And right now, it’s just kind of a free for all.”