Harvest CROO

A Florida-based technology company that’s been developing a strawberry-picking robot for years has finally started unveiling the product—first for news segments, and next month, with a demo for growers attending an annual industry convention in Orlando. That’s potentially a big deal. Grain farmers have harvested their fields with autonomous, self-driving combines—with varying levels of success—since John Deere debuted its first model over 20 years ago. Produce, however, requires a lighter touch, and berries, in particular, are damn near impossible to pick robotically.

Imagine a robot that could replace those workers. The machine developed by Harvest CROO, the company I mentioned above, attempts to do just that. The prototype—a big, hulking thing, like a pontoon boat on wheels—inches over eight rows of strawberries at a time. As the beds pass beneath, 16 robotic arms attached to a single chassis spin and whir to lift the leaves off the plant, take photos of the berry, and with a plastic clamp, pluck the red ones off the stem. Then, internally, the machine loads the fruit into plastic clamshell containers with a packing capacity of 1,000 pounds.

“Think of the old Terminator movies, with the robots spinning around and picking things out,” says Paul Bissett, the company’s recently installed CEO. So his company is making a Terminator for strawberries? “Yes, exactly!”

Harvest CROO

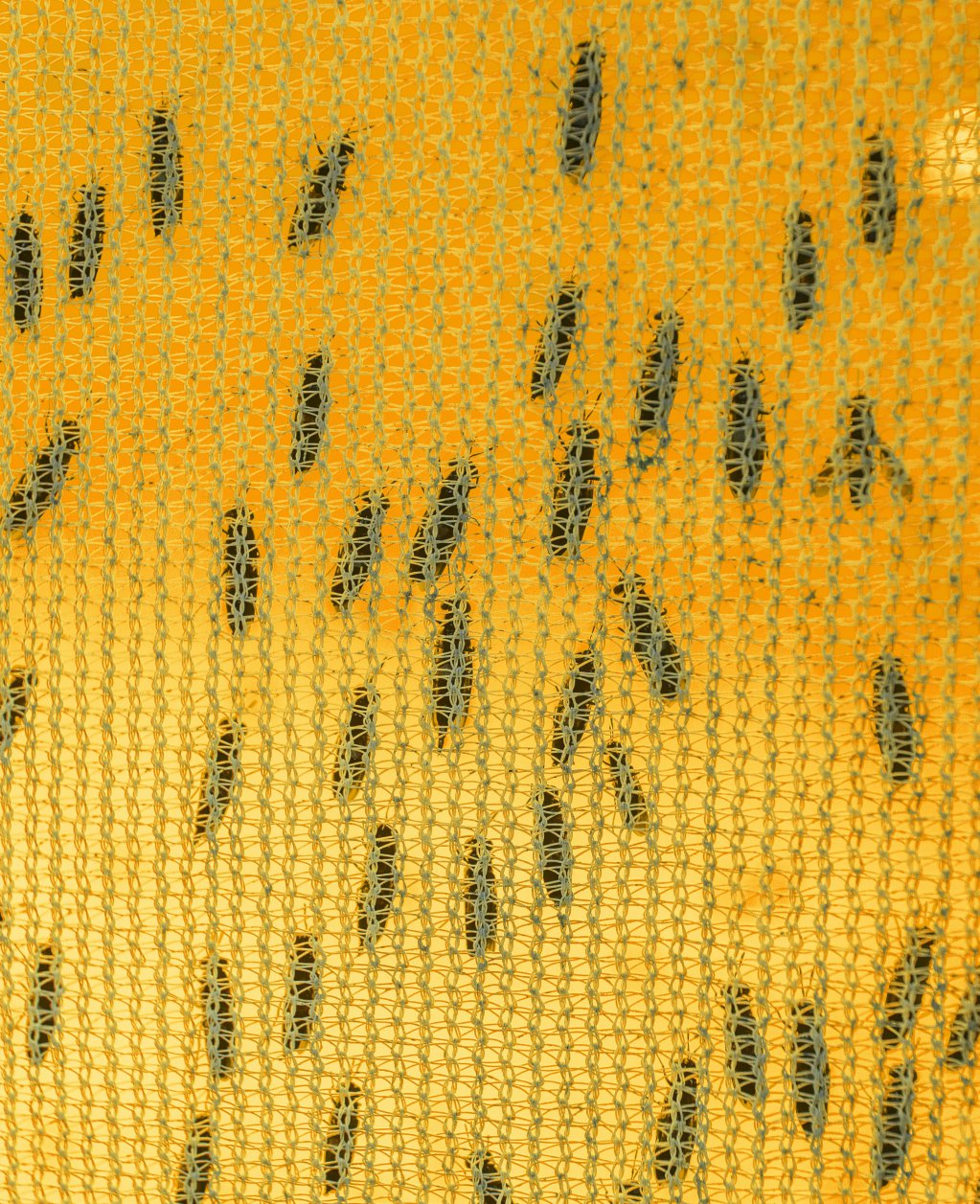

Harvest CROO At commercial scale, running in 20-hour shifts, the machine could cover eight acres in a day, doing the work of 30 pickers

Bissett is a computer scientist with a background in machine vision. One of his first companies, the Florida Environmental Research Institute, developed systems for high-altitude Department of Defense aircraft to monitor waters and beaches. One such project, dependent on color imagery, was posited specifically to identify terrorists sneaking in through ports. “Strawberries are a lot easier to target,” he says.

Bissett says growers who use the machine, called the “Berry,” won’t buy the robot. They’ll buy a service, with technicians and specialists guiding the application. To make the Berry run, and identify strawberries, what it sees must be a simple landscape, pared down to three colors: black, the color of the plastic tarp that covers the bushes; green, the color of the leaves that the clamps must lift; and red, the color of the berry that has to be picked. It’s more accurate to say that growers are actually buying into an entire system of farming. It’s not unlike the way a grain farmer plants corn to be combined by a Deere tractor, and depends on Deere technicians to maintain and improve the machine.

The Berry, however, is still in field trials, and three years away from a commercial launch. That’s not because the machine doesn’t know what a ripe strawberry looks like—the picking algorithm is based on images of thousands of berries that the company has been collecting for five years, Bissett says. Instead, it’s because CROO still hasn’t figured out how to do its essential function—autonomously picking and handling fruit as delicately as a human does—with just the right speed and tension so that it doesn’t get bruised on its journey from stem to clamshell package.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2bcOggQmjpY

If it’s true that Harvest CROO’s machine is years away from commercialization, the promise still is significant. The introduction of a robotic worker that doesn’t need a visa, can work at night in rain or shine for the duration of a season, and won’t bail to pick table grapes instead, could spark a paradigm shift in the strawberry industry. Sure, it moves slower than a trained human: at its fastest, it crawls at three inches per second. But at commercial scale, running in 20-hour shifts, the machine could cover eight acres in a day, doing the work of 30 pickers. Running a strawberry farm would be closer to operating an assembly line, then. The process would be reliable, centralized, standardized. And it’d be cheaper than hiring more fleets of human hands.

“The California strawberry industry has been suffering from a persistent shortage of harvesting labor for years,” says Lucky Westwood, vice president of operations at California Giant, an international berry company based in Watsonville, California that represents about 10 percent of the California market, and is one of many growers investing in the machine, in an email to The New Food Economy. In his mind, the machine won’t be replacing labor, so much as filling the gaps on unharvested acres that are too costly to harvest. That’s because, he says, more farm workers means “longer hours, higher cost, and sometimes lower quality.” There’s no grower in California that wouldn’t like to have “quite a few more people available for harvesting,” he says.

What would he need to actually implement mechanical harvesting in California Giant’s fields? “Simply for it to work well.”

Harvest CROO

Harvest CROO For Harvest CROO’s CEO, advancing technology is just about making sure farmers have something reliable to depend on and eliminating another variable when so much else shifts at whim, like prices and weather

It’s not just about efficiency. Automation-oriented solutions also allow producers to sidestep the contentious debates about the role of migrant labor in the food supply. Immigration from Mexico, Bissett points out, is slowing down. At the same time, pay for seasonal labor continues to rise—both in states like California, where farm workers will reach a minimum of $15 an hour by 2022, and nationwide, where guestworker pay is reaching the point where agricultural producers are suing the U.S. government. As if to say: What’s the point of hiring a migrant laborer if they cost as much as native-born Americans?

Bissett, for his part, doesn’t think the advancing technology is about replacing labor. For him, it’s just about making sure farmers have something reliable to depend on and eliminating another variable when so much else shifts at whim, like prices and weather. In his telling, there just aren’t enough migrant laborers to get the most of the country’s nearly 60,000 acres of strawberry fields. The choice, then, to search for more field crews, or get onboard with the Berry machine, should be clear. Farmers: come with Harvest CROO if you want to live.