Graphic by Alex Hinton/iStock/Cesar Okada/Sabih Jafri/Frank Wagner

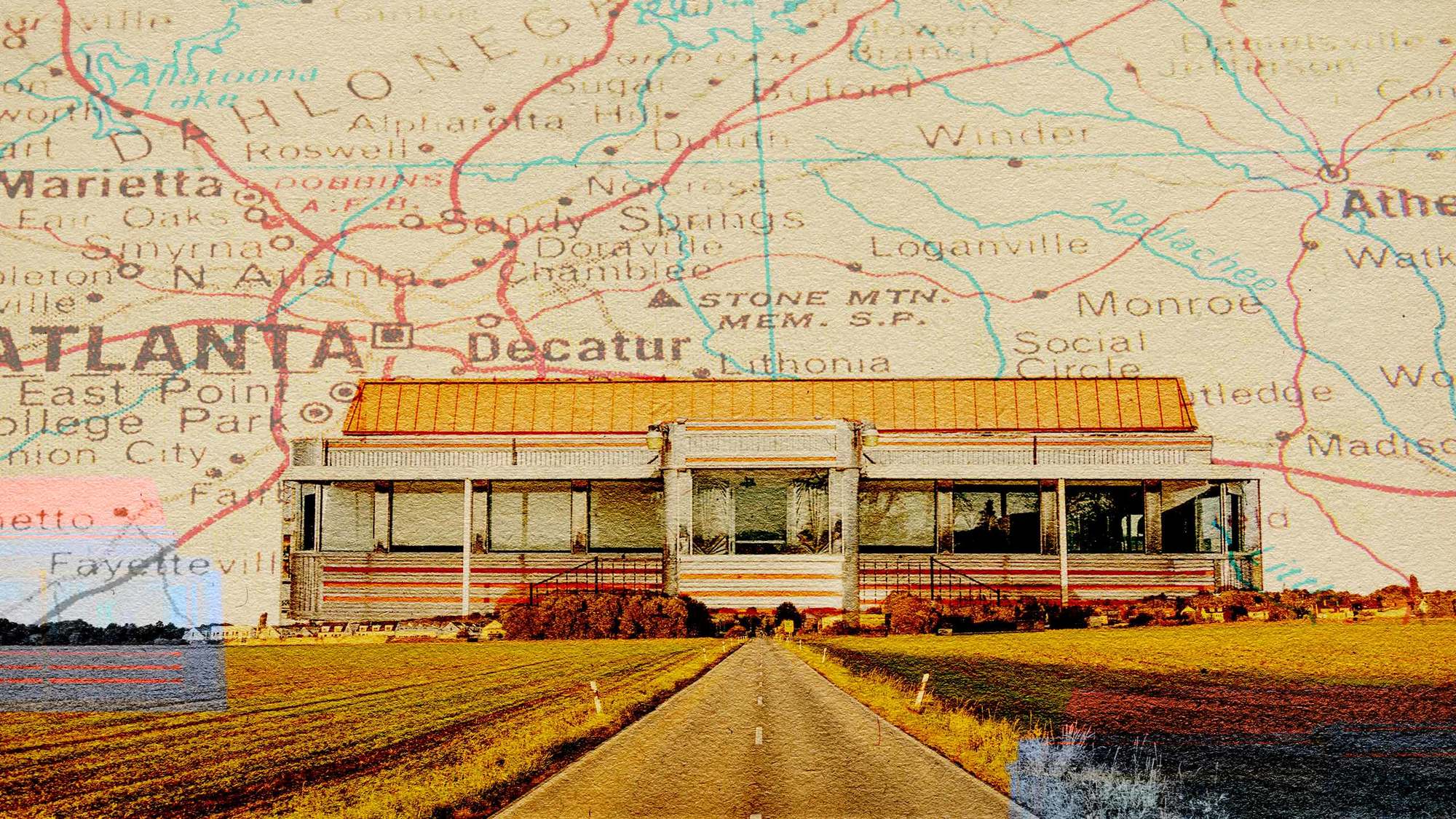

Small-town restaurants might not be in the national spotlight, but they’re the center of the universe for small communities and a growing number of crowd-averse tourists.

Ila Restaurant, a meat ‘n’ three restaurant named after its Georgia hometown (pop. 400), is a one-story building just north of the four-way stop sign off Main Street. Today’s steaming lunchtime buffet includes fried chicken, mashed potatoes, biscuits, and assorted vegetables. Many of the Formica tables and booths are full with families, older couples, and groups of men in work garb on a lunch break. One of the servers wears a white Nike cap and a navy tee that says “Team Jesus.”

I load my plate with sides, then ask the server if the fried chicken is breaded, because I have a gluten allergy. Without my asking, she directs the kitchen staff to grill some chicken for me, no problem. A few minutes later, she delivers three large pieces of chicken to the table and pours me another glass of unsweet tea.

Ila Restaurant owner Jackie Sinclair, 59, joins her kitchen crew daily in preparing food for her meat ‘n’ three in Ila, Georgia. She has no plans to retire but thinks, given the restaurant’s success, she would find a buyer.

Allison Salerno

Rural restaurants are a small constituency, and in fact the Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the federal Small Business Administration (SBA) don’t even agree on what “rural” means. The USDA follows the U.S. Census’ lead, defining rural as “communities with fewer than 2,500 residents.” In contrast, SBA’s definition of rural is so broad it includes places like Lincoln, Nebraska, population 283,000 and growing. Restaurants in towns like Ila fly under the radar compared to urban and suburban places.

Fifty-five percent of Georgia counties are rural, with nearly the same proportion of food-related jobs as in urban counties—8 percent as compared with about 8.6 percent.

Nick Flores, who owns Nick’s Place in Crawfordville, didn’t apply for pandemic grants because he doesn’t believe in government aid of any kind. He’s gotten by, so far, by living frugally and dipping into his own savings. Jackie Sinclair, who owns Ila Restaurant, applied for and received two PPP grants and $70,000 in Restaurant Revitalization Funds. Without that money, she said, she would have gone out of business because she had to shut her doors for weeks at the pandemic’s start.

Allison Salerno

Nick Flores, 60, retired from a corporate career with Hyatt, opened Nick’s Place in the state’s least populated county at the pandemic’s height. His restaurant has become a hub for community gatherings.

Independent restaurants in many small Georgia communities are not only holding their own but outperforming their counterparts in Atlanta and other metropolitan areas, according to research by John Salazar, coordinator of the hospitality and food industry management program at the University of Georgia. Salazar, also an associate professor of hospitality management, defines rural counties as counties unaligned with metropolitan statistical areas—a definition more closely linked to the USDA’s than the SBA’s. By his measure, 55 percent of Georgia counties are rural, with nearly the same proportion of food-related jobs as in urban counties—8 percent as compared with about 8.6 percent. The rural counties’ 2020 decline in hotel occupancies—which significantly affect restaurant visits—was 16.7 percent, much less than the 28.2 percent occupancy decrease for urban counties.

Rural restaurateurs enjoy one remarkable economic advantage: far cheaper real estate prices than in Atlanta and other cities. After renting space in downtown Crawfordville for a couple of years, Flores spent $90,000 of his own savings to open up a 85-seat restaurant last November—$20,000 to buy a 4,000-square-foot downtown department store that had been shuttered for decades and $70,000 to renovate it. Property taxes are $1,200 a year. His restaurant is ringing up $900 in daily sales with a staff of two paid employees, plus him. Flores said he clears $600 a day after expenses. Sinclair pays just $3,000 a month rent for Ila’s 5,000-square-foot restaurant, or 60 cents a square foot, about half of what an urban rent would be.

Commercial rates have remained low even as residential values rise in Madison County (pop. 30,000) because newcomers want large lots, strong public schools, and easy commutes to jobs in Athens. “You’ve got to have the buyers,” said Stanley Thomas, a 67-year-old lifelong county resident and local realtor, and less than vibrant downtowns mean low demand for retail spaces. “We don’t have the population to attract a lot of commercial spaces” since new businesses are less likely to set up shop in Madison County when Athens is nearby.

“We’re seeing the rural communities be in a position that they haven’t been in before, which is they’re really poised to make an impact on the broader state tourism product.”

But there’s been an increase in tourism in rural areas, according to Salazar, because people are better able to socially distance themselves, which improves the profit side of the ledger. “We’re seeing the rural communities be in a position that they haven’t been in before, which is they’re really poised to make an impact on the broader state tourism product, because there hasn’t been a full-on return for the urban market just yet,” he said. Until I interviewed him, I hadn’t considered my husband and myself “nature-based travelers,” though our pandemic hobby has been to leave Athens, where we live, to hike each of Georgia’s state parks. A recent Saturday found us an hour’s drive from home in Taliaferro County—Georgia’s least populated, and the second least populated county east of the Mississippi River.

After a hike in A.J. Stephens State Park, we drove to Crawfordville, the county seat, for lunch. At Nick’s Place, we met Flores, 60, who opened his restaurant after a 25-year career with Hyatt Hotels, including his last position as executive sous chef at the Hyatt Regency Washington on Capitol Hill.

Allison Salerno

Customers line up at Ila Restaurant’s lunchtime buffet.

For residents of Crawfordville and other communities, restaurants occupy a critical community space, serving as a source not just of food and entertainment but also of social connection. Without Ila, the town would be “hollow,” said Sinclair, its center a four-way stop sign on a two-lane state highway, with few other businesses. Leslie Martin, a Crawfordville resident, said Nick’s Place “has absolutely provided social connection for the community” that lacked restaurants or even a grocery store. “We had nothing,” she said. Martin, a retired chef, was so convinced of the value of Nick’s Place that she drove an hour in various directions to auctions in nearby cities to help Flores furnish the restaurant.

Every Friday morning at 7 a.m. for the past 31 years, the Rotary Club of Madison County has been meeting in a large dining room in the back of Ila Restaurant. The building’s owner, a Rotarian, built the addition for club meetings; it’s open to any customer outside of meeting times. The morning I visited, the restaurant’s parking lot was full of pick-up trucks and sedans. About 25 Rotarians had gathered inside to dine on grits, eggs, and bacon from the front room’s breakfast buffet before they settled in with cups of coffee and sweet tea to listen to the day’s speakers.

“This room has really become a community meeting room,” said state Sen. Frank Ginn, 59, a charter member, whose table I joined. “Do you remember watching ‘It’s a Wonderful Life?’ Well, you never know the impact you have and the good that has happened in Madison County” as a result of residents being able to meet and connect at the restaurant.

Allison Salerno

Morgan Barnett, 30, and her younger son, Jaxson, 3, are regulars at Ila Restaurant’s buffet-style breakfasts on weekday mornings. They sit at this table with a group of mostly retired neighbors.

For Morgan Barnett, 30, Ila Restaurant has been a source of unexpected friendship. A married mother of two young boys, Barnett shows up with her younger son nearly every weekday morning, after her husband goes to work and their older son to school, to have breakfast with a group of retired local men who once were strangers.

The hardships these restaurants face are also specific to their location, the flip side of that attractive isolation: They have to figure out how to market to visitors and travelers who might otherwise not discover them; how to contend with high food and delivery costs while keeping meal prices affordable for locals; and how to plan for the future in what are often graying rural economies.

Outside coastal tourist communities, rural Georgia means two-lane roads where vistas are farmland or forests, and where even the “center of town” might not look like much to an outside eye. Restaurants there can be hard to find—and hard to sustain. Every Sunday morning at 7, Flores and an employee load his Dodge Ram truck with four empty ice chests for the nearly two-hour drive to Restaurant Depot in Buford, north of Atlanta, to stock up on a week’s supply of eggs, French fries, chicken tenders, and meat for Philly cheesesteaks. It’s too expensive to use Houston-based Sysco Corp., for food deliveries, which used to put a $1,200 dent in his monthly profits, between the $45 delivery fees* and the higher cost of food. “Sysco has great products, but they were charging for everything,” Flores said.

And then there’s the issue of succession when today’s restaurant owners retire. Salazar believes that the average age of restaurant owners is rising, like the average age of Georgia farmers is rising—57.9 years according to the last U.S. Census of Agriculture—as younger generations seek opportunities outside the family business. Sinclair’s daughter has settled with her family in suburban Atlanta, where she works as a therapist, though Sinclair is confident she can find a buyer for her business when it’s time to retire. Flores said he is not focused on the future of Nick’s Place. “As long as I have two hands, I will be here,” he said. “I’m going to die here.”

“As long as I have two hands, I will be here. I’m going to die here.”

There’s still a sign for Hot Thomas Bar-B-Que on Greensboro Highway in Oconee County, Georgia, but the family-run restaurant closed for good in August 2020. The late C.H. “Hot” Thomas began the business selling chicken halves cooked over a big charcoal pit, basted with a ketchup-based sauce, to University of Georgia football fans. He converted a general store that had been in his family for decades, on hundreds of acres of family farmland, into a sit-down and takeout restaurant serving pulled pork, ribs, chicken mull—a regional stew of crackers and chicken—and chicken quarters.

Tony Waller, 53, lives nearby and was a regular. “It was consistently good, always good. It was fairly standard central Northeast Georgia smoked whole hog barbecue. Cooked over coals,” said Waller.

Thomas’ son and daughter-in-law took over the business after his death in 2011. But when they retired from the restaurant in 2020, their three adult children were disinterested in taking over. “It had all happened in one week,” said Morgan Thomas Davis, 28, the eldest child. “And my mom was like, ‘I am not doing this by myself.’”

Morgan Thomas Davis, 28, helped her parents run Hot Thomas Bar-B-Que until it closed in August of 2020. She and her husband now own and operate a fitness gym five miles north of the shuttered restaurant.

Allison Salerno

A fitness center called CoreBlend, five miles north of the shuttered restaurant, has a growing clientele who spend hundreds of dollars a month on the membership, and Davis jokes that Hot Thomas Bar-B-Que produced some of the gym’s best clients. She met and married her husband, CoreBlend’s founder, at the gym, and for a while worked at both places. But in 2018, she had to choose between helping her husband with his thriving enterprise and managing the restaurant. She chose the gym. “Basically my mom fired me, made the decision for me, in the most loving way possible, ” Davis said. “She was like, ‘You’ve got to go, you’ve got to go do this.’”

Running a restaurant is harder as one ages, especially without younger family members to help; Sinclair, who has Type 2 diabetes, stopped serving food on Sundays—at $5,000, her biggest sales day—in part because of the physical strain of preparing mashed potatoes from scratch, chicken pot pies, and other dishes.

Allison Salerno

Ila Restaurant owner Jackie Sinclair, 59, takes a break from food prep in her restaurant kitchen. She said federal funds were key to keeping her restaurant afloat during the pandemic.

“I can’t do what I could do five years ago,” she said. “Just to help out my staff and to make it easier on everybody, I would come in at 3:30, Sunday morning, and start cooking. My other staff, regular staff would start coming in at 6. And then I could breathe after that.” As we talked in her back office, Sinclair’s cell phone kept buzzing to let her know her glucose levels were too high.

“I have a 12-hour day,” Sinclair said. “I’d have a 12-hour day on my feet and no breaks every day.” She decided to close on Sundays because she was having to ask her husband, busy with his own insurance company, and her daughter, who lives an hour’s drive away, to lend a hand. But Sinclair discovered that her weekly sales did not decline; loyal local customers would stop by during the week instead.

The next step, according to Salazar, is to connect with a bigger audience, including the larger hospitality and tourism ecosystem in Georgia. “Travelers are shying away from these major urban markets, and they are looking for activities and experiences that are more conducive to social distancing,” he said. “I have been doing tourism and hospitality research for over 25 years, and very rarely have I seen an opportunity where rural tourism and agritourism have this opportunity to step into the spotlight.”

*Clarification: After publication, a representative for Sysco Foods reached out to say that the company started waiving delivery fees in November 2020 “to help small independent restaurants like those owned by Mr. Flores.”