iStock / JJ Gouin

The herbicide can be sprayed with added restrictions for another five years.

Earlier this summer, a court ruling and subsequent Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) order threatened to throw farmers for a loop: The government was banning dicamba, a controversial herbicide that drifted from farm to farm, damaging neighbors’ crops and local flora.

Trouble was, the decision came after many growers had already planted seeds that were genetically modified to tolerate being sprayed by dicamba. Without it, they worried their soy and cotton fields would be overrun with weeds. The agency ultimately relented, allowing farmers to spray the banned weed killer through much of the summer.

This week, the EPA reversed course again: It announced it will allow chemical companies to re-register dicamba, meaning farmers can spray it on their crops for the next five years, albeit with a few more restrictions. It will also require farmers to mix herbicides containing dicamba with a compound meant to reduce volatility.

The news was greeted with relief by farm groups and chemical companies. “Growers have been clear how vitally important this tool is for their weed-management programs,” said Bayer’s dicamba manager Alex Zenteno in a press release. In 2018 Bayer acquired Monsanto, which had invested huge amounts of money in developing dicamba-tolerant seeds, despite warnings from scientists that the herbicide could cause drift problems. The American Soybean Association released a press release thanking the EPA for supporting “the continued success of our industry.”

“EPA rushed re-approval as a political prop just before the election, sentencing farmers and the environment to another five years of unacceptable damage.”

Environmental groups were, predictably, less pleased. “”Rather than evaluating the significant costs of dicamba drift as the 9th Circuit told them the law required, EPA rushed re-approval as a political prop just before the election, sentencing farmers and the environment to another five years of unacceptable damage. We will most certainly challenge these unlawful approvals,” said George Kimbrell, legal director for the Center for Food Safety, in a press release.

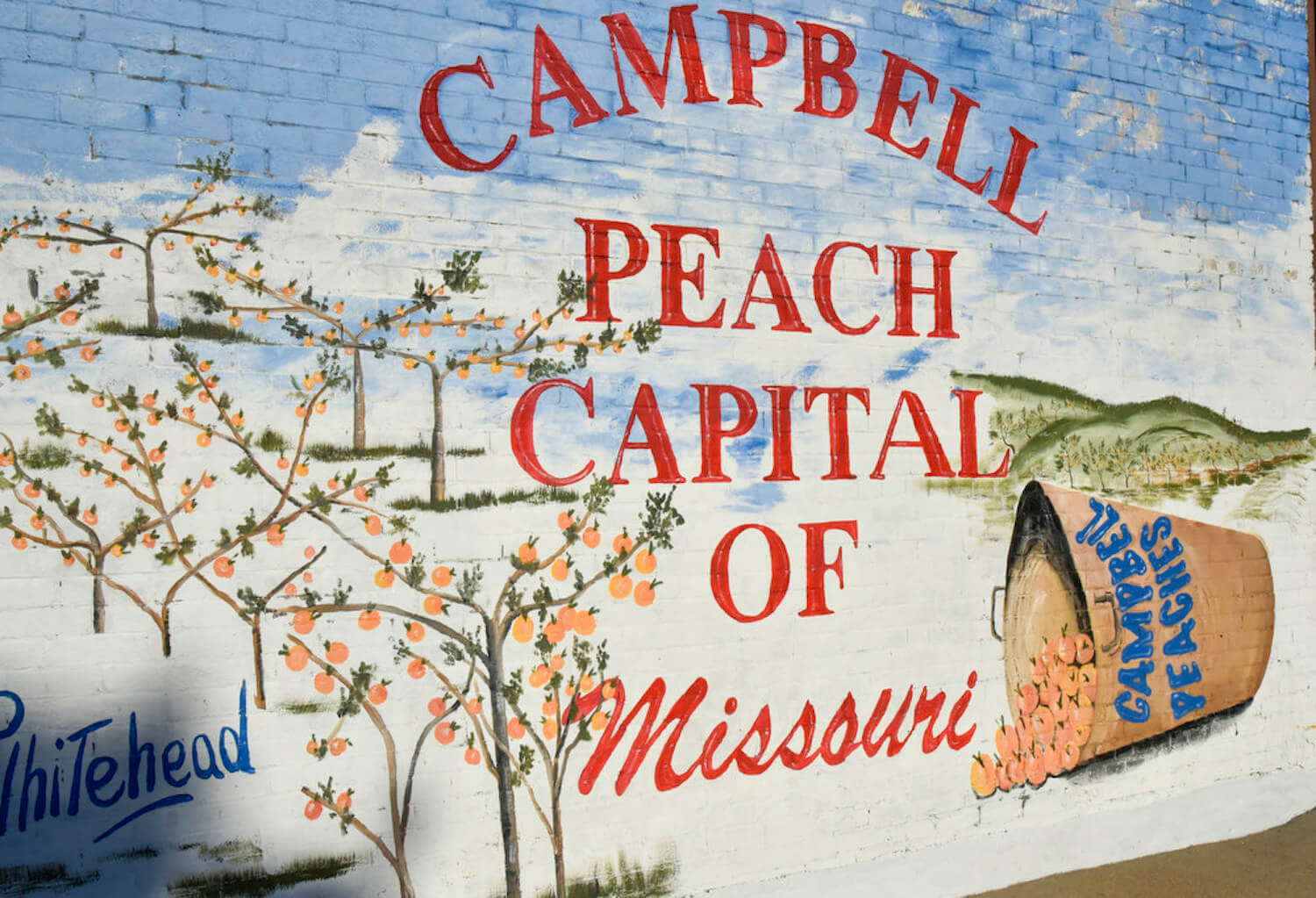

Dicamba has caused drift problems for several years now, despite efforts by federal and state regulators to minimize its volatility. A peach farmer in Missouri won a $265 million judgment against chemical companies over drift complaints earlier this year; the herbicide has been blamed for killing tens of millions of trees across the Midwest. Scientists are also examining potential correlation between dicamba use and liver and bile duct cancer among farmers who use it over a long period of time.

[Subscribe to our 2x-weekly newsletter and never miss a story.]

The EPA was initially forced to vacate the dicamba registration as part of a ruling by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled in June that the agency violated a law that regulates pesticides when it initially approved the weed killer. The lawsuit—which was brought by family farm groups and environmental advocates—alleged that the EPA didn’t review enough evidence when it approved the product. Particularly telling: It did not evaluate a single study that examined the impact of off-target dicamba drift on soybean yield.

It remains to be seen whether the new restrictions on dicamba application—namely, shorter spraying windows, larger buffer zones, and mandatory addition of compounds to balance the weed killer’s pH—will prevent the herbicide from damaging crops. Farmers and advocates have complained that past restrictions are impossible to follow; some argue that the rules on the label function more as legal cover for chemical companies to blame farmers for drifting pesticides than real preventative measures. “Given EPA-approved versions of dicamba have already damaged millions of U.S. acres of crops and natural areas there’s no reason to trust that the agency got it right this time,” said Nathan Donley, senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, in a press release.