My bedside reading this week was Emerging Pathogens in Meat and Poultry, a new study from the Pew Charitable Trusts that tries to capture just where we are in the eternal battle between people and the bacteria, viruses, parasites, and prions that infest the food we eat.

The title may suggest a simple laundry list of foodborne bad guys that you’ve never heard of (and there are certainly a few of them in there), but the report itself is far subtler. “Emerging,” it turns out, is a fairly complicated idea.

For me, the biggest surprise in the report was how slowly our knowledge of foodborne pathogens has evolved. We’re so used to thinking about the major foodborne pathogens—salmonella, listeria, E. coli—that it’s easy to forget that their role in human disease is a relatively recent discovery, in many cases dating back only to the 1960s and 1970s.

The prototypical example: It was 1975 when scientists first isolated the strain of E. coli known as O15:H7, but it wasn’t until seven years later, in 1982, that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), responding to a pair of outbreaks associated with ground beef, identified the strain as a foodborne pathogen. You know the rest of the story: In 1993, O15:H7 in undercooked hamburgers at the Jack in the Box restaurant chain sickened more than 500 people, and four children died. The government finally took decisive action, declaring the pathogen an adulterant (which meant that meat found to contain the bug couldn’t be sold) and instituting the Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point (HACCP) system of food safety, which transformed U.S. food production.

The report is filled with stories of slowly emerging understanding. This is the most striking: “In A.D. 900,” the authors explain, “Byzantium’s Emperor Leo VI forbade—under threat of exile and loss of all possessions—the making and eating of blood sausage, prepared in pigs’ stomachs and then smoked. It was believed that miasmas, or infectious vapors, emitted from the sausages would result in a paralytic infection. This disease was called ‘botulism,’ after ‘botulus,’ the Latin word for sausage. Botulism’s true cause, a toxin produced by a bacterium named Clostridium botulinum, would not be discovered until 1895, when Emile Pierre van Ermengem at the University of Ghent in Belgium studied an outbreak associated with smoked ham.” A thousand years to figure out a known pathogen. Thank God we are a bit more nimble today.

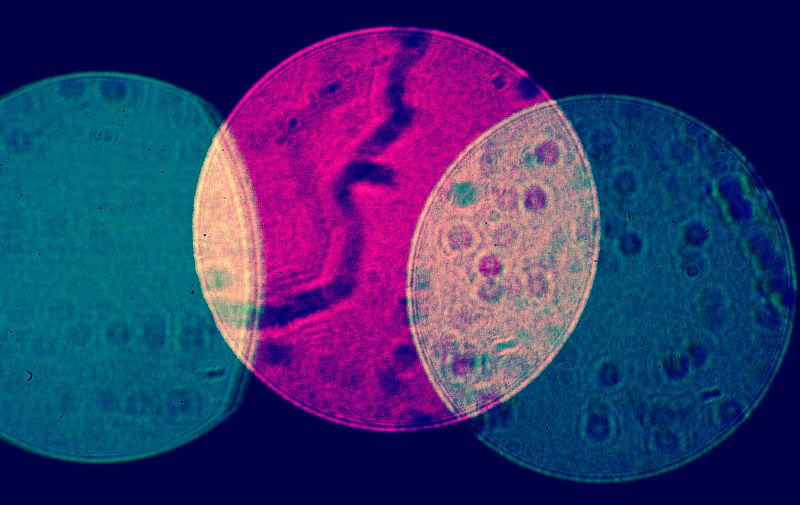

Graphic by The Pew Charitable Trusts

Graphic by The Pew Charitable Trusts But we shouldn’t be complacent: O15:H7 is what’s known as a Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC), and it’s far from the only one. More than 100 strains of STEC are known, and outbreaks linked to non-O15:H17 strains of STEC have been rising sharply over the past ten years—probably at least in part because of increased attention on the part of food safety agencies. In 2011 USDA added six additional strains of STEC to its list of adulterants, including O111, a strain that is linked with hemolytic uremic syndrome, a disease marked by destruction of red blood cells and acute kidney failure. More are undoubtedly on the way, both because scientists will discover new pathogenic strains (or will link known ones to diseases they cause), and because strains will evolve to become more pathogenic, more virulent, or more drug resistant.

And new links between pathogens and disease continue to be made.

Microbial hazards in food are always changing.

There’s Arcobacter butzleri, for instance, a bacterium closely related to the Campylobacters that can cause diarrhea in humans. It’s been found in poultry for years, but it was only in 2008 that it was linked to a foodborne outbreak of disease, transmitted by chicken served at a Wisconsin wedding reception. There’s Clostridium difficile, long known for its role in hospital-acquired infections. Since the 1990s, there has been an uptick in the number of Clostridium infections and increasing reason to think that the bacterium is being spread not just by hand but by food, though we’re still waiting on proof. Among the viruses, Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) is known to cause a hemorrhagic fever that is fatal in 10 percent to 40 percent of cases. It’s known to be present in domestic animals and spread by ticks. It’s thought that the disease can be spread by contact with blood in preparing food, but we still don’t know.

And though we’re much better at identifying pathogens, we aren’t as far along in controlling them as you might have guessed. The introduction of HACCP caused a substantial drop in the rate of foodborne infections, but progress has been stalled for a decade or more.

Graphic by The Pew Charitable Trusts

Graphic by The Pew Charitable Trusts Or perhaps not. The report makes it clear that statistics on foodborne infections reflect a complex reality. “Microbial hazards in food are always changing,” it concludes. “Humans, farm animals, wildlife, and microorganisms—both pathogenic and Nonpathogenic—live in an evolving environment and constitute a dynamic and interconnected ecosystem. Changes in food production practices or consumption patterns can result in new possibilities for the introduction, proliferation, and transmission of pathogens. Food production practices and consumption patterns change over time. New pathogens may emerge, or known pathogens may evolve to exhibit new traits. Pathogen strains may adapt to new animal reservoirs, acquire factors that increase their virulence, or acquire genes that confer resistance to antimicrobials critical to the treatment of disease in humans and animals. Demographic shifts also may determine which risks might emerge or re-emerge in the future.”

So wash your hands, wash your lettuce, forget you ever heard the five-second rule, polish up that HACCP plan, and tell your congressman you’re concerned about antibiotic resistance? Maybe. But at a time when we’re concerned with moving the food system more in the direction of the natural, it doesn’t hurt to be reminded that nature is not universally benevolent. This world belongs less to us than it does to the microorganisms. It doesn’t mean we have to surrender to them and admit defeat, but the need for systemic vigilance is never ever going to go away.