Claire

On Friday, Donald J. Trump is going to become the 45th President of the United States. That’s got a lot of people worried, but this week we noticed some hand-wringing where we didn’t quite expect it: among the dairy farmers of South Dakota.

First, some context. Dairy, like most sectors within the agricultural industry, is very dependent on immigrant labor. According to a 2015 study from Texas A & M’s Agrilife Research Center, immigrants comprise about 50 percent of the dairy workforce. And farms that use immigrant labor produce almost 80 percent of the country’s milk. The study posits that “eliminating immigrant labor would reduce the U.S. dairy herd by 2.1 million cows, milk production by 48.4 billion pounds and the number of farms by 7,011.”

Trump, if you haven’t heard, has a thing for tighter borders—and the dairy industry fears it’ll be increasingly vulnerable as political tides turn.

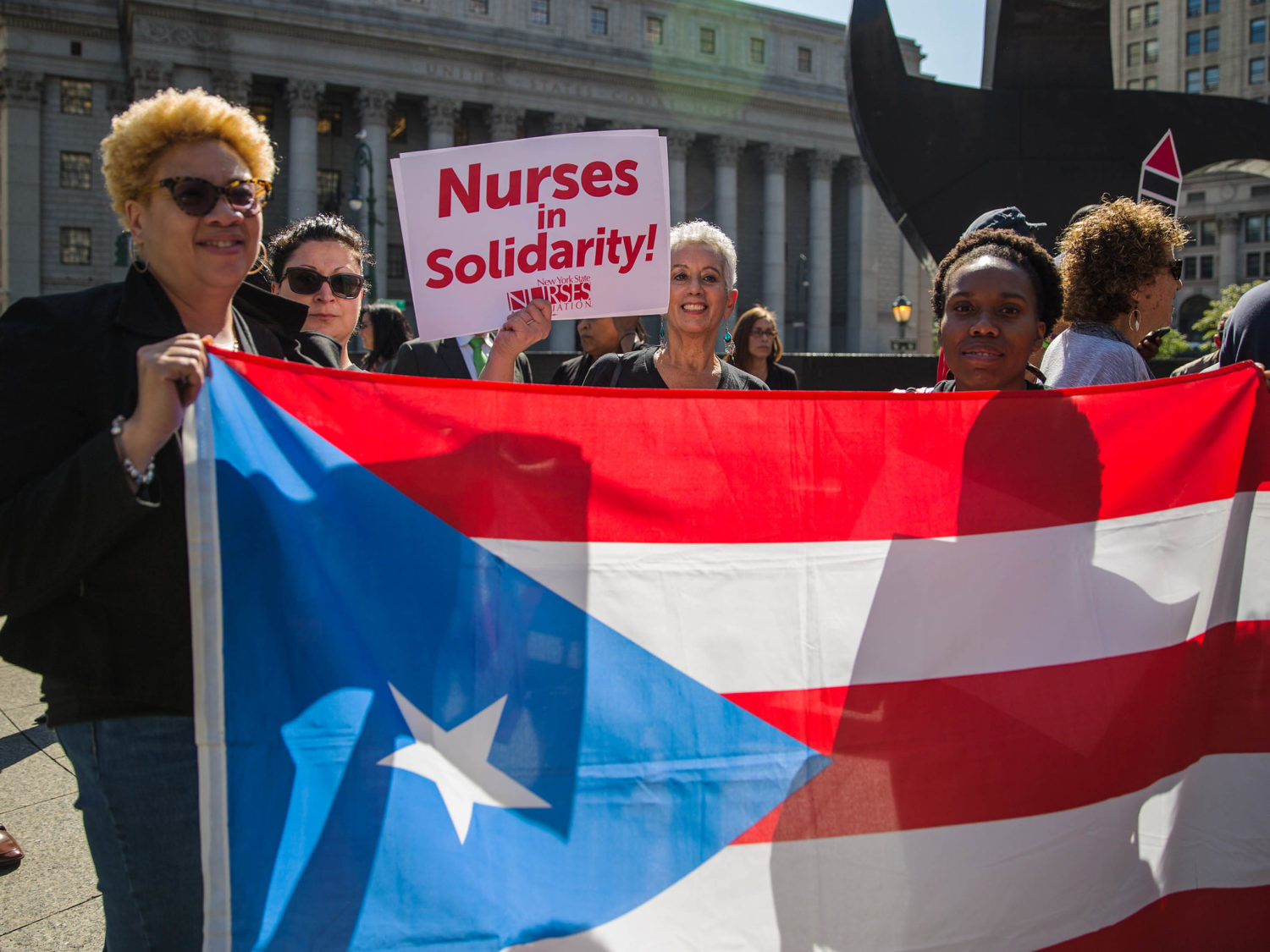

That anxiety may underlie South Dakota’s efforts to tap a new labor pool: Puerto Ricans. According to Dairy Reporter, a South Dakota State University (SDSU) Extension team is working with the Puerto Rico Department of labor to promote the state’s dairy jobs, hosting recruitment sessions in three cities—San Juan, Ponce, and Mayaguez. At first glance, it seems like a natural fit. The unemployment rate on the island was 11.9 percent last November. And Puerto Ricans, of course, are passport-carrying American citizens, unaffected by fiery political rhetoric about border walls and refugees.

Still, jobs were a major issue driving the 2016 election. Why should South Dakota’s dairy farmers have to go all the way to Puerto Rico to find American workers? Mike McMahon, an upstate New York dairyman, put it this way in 2015: “Nobody wants to go out there and deal with cows and get manure up their sleeves.”

The fact is that most native-born citizens simply aren’t willing to do farm work, almost no matter how bad the economy gets. Fruit and vegetable farms can issue temporary H-2A visas to seasonal foreign workers if they can demonstrate they’ve tried to hire native-born Americans first. But in general, few respond. The struggles of the North Carolina Growers’ Association are one instructive example. In 2011, it advertised 6,500 open positions. Only 163 candidates showed up on the first day, andonly 7 workers survived the entire season. This, during a period when the state’s unemployment rate hovered above 10 percent for 12 months.

But the dairy industry isn’t authorized to issue H-2A visas because its employees, who work year-round, are considered permanent. As such, it’s even more reliant than crop farming on unauthorized foreign labor—and even more skittish about the incoming President.

The scope of the SDSU’s Puerto Rico pilot is modest: the university hopes to bring only 20 workers over at first, a drop in the proverbial milk pail. But because Puerto Ricans can travel freely between the territory and the mainland, the question isn’t really if they’ll come. It’s how long they’ll stay.