Joe Fassler

In January 2016, kids peering into their bowls of Trix cereal at breakfast found that the thrill was gone. The bright colors—lemony yellows, orangey oranges, and grapity grapes—had been replaced with more autumnal, somber hues. Instead of synthetic dyes, General Mills’ famous spheroids of puffed corn had been tinted with turmeric, carrot extracts, radish juice, and other natural colors. “Lime green” and “wildberry blue,” intensely neon shades the company’s scientists could find no natural ways to duplicate, had vanished entirely.

This feature received a 2019 James Beard Foundation Journalism Award for health and wellness reporting.

The resulting bowl looked drab and dull. But in theory, the change—which included swapping out high- fructose corn syrup for plain old sugar and corn syrup, and using only “natural flavors”—was a response to customer demand. “We’re simply listening to consumers and these ingredients are not what they’re looking for in their cereal today,” said Jim Murphy, president of General Mills’ cereal division, ahead of the launch. But the makeover met with harsh backlash, especially online. (“It’s basically a salad now,” one disgruntled lawyer whined.) By October 2017, all “six fruity colors” were back on shelves as “Classic Trix,” though the reformulated version continues to be sold.

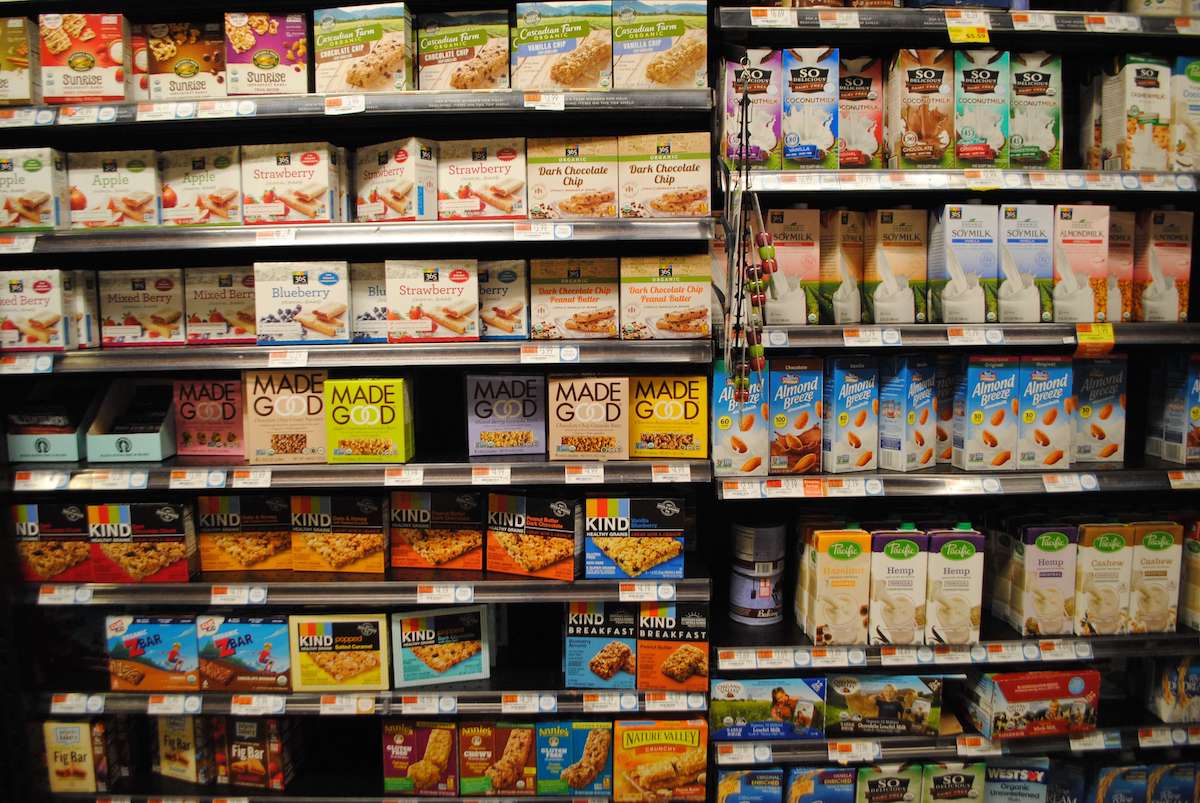

Green and blue Trix were, for a brief moment, victims of one of the biggest trends in food production: “clean label.” The term still hasn’t reached broad currency outside the industry, but virtually anyone who shops has seen its impact on the grocery aisle. Starting around 2010, and with increasing momentum, ingredient lists began to shrink, with fewer spooky chemical names. The biggest names in packaged food—including Kraft Heinz, Campbell Soup, Nestlé, and Hershey’s—have lined up to jettison artificial colors, flavors, and preservatives, revamping products with shorter lists of recognizable ingredients. Meanwhile, smaller upstarts like RX Bar and Sir Kensington’s wield clean labels as a competitive weapon, angling for market share with ingredient lists so minimal they read like recipes.

On the surface, this may seem like the unprocessing of processed food. But the incredible shrinking ingredient list is a much stranger phenomenon than it at first appears. It’s more about optics than it is about health. It’s more about language than it is about specific ingredients. And it’s more about catering to a culture’s fears and biases than the genuine pursuit of better-for-you food.

Clean and simple?

“If you can’t say it, don’t eat it,” preached journalist and author Michael Pollan in a 2008 NPR interview promoting his book In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto, where he also prescribed avoiding foods with more than five ingredients on the label. Pollan’s rule of thumb, a strategy for avoiding “highly processed” foods, reflected a growing suspicion of food technology—which seems only to have increased since then.

Pollan’s suggestion, at least in part, was intended to encourage healthier eating through whole foods and home cooking—anyone avoiding unfamiliar additives is more likely to reach for an apple than a sack of potato chips. But America seemed to heed his advice only selectively. We kept the processed snack foods. Now they just come with fewer four-syllable ingredients.

Today, “healthy” snack sales are booming as the public becomes more additive-averse, scrutinizing labels with a suspicion that borders on indiscriminate chemophobia. Google nearly any food chemical, and you’ll find reasons to fear. Maltodextrin, a starch used as a thickener, is a “metabolism death food,” according to popular “wellness physician” Dr. Axe. Carrageenan, a seaweed-derived emulsifier commonly used in non-dairy milks, might be “wrecking your gut,” according to Organic Life. Lifestyle blogger Vani Hari, better known as “The Food Babe,” has declared all “natural flavors” to be “chemical warfare.”

Marketing language on Simple Mill’s almond flour crackers

Simple Mills and NFE

All this has taken its toll on consumer confidence in the food supply. According to the International Food Information Council (IFIC), in 2016, 38 percent of consumers named “chemicals” as their top food safety concern, up from 9 percent just five years earlier. This suggests that large numbers of ordinary Americans no longer trust the assurances of scientific experts or government agencies about the safety of food additives—much less corporations—not to put weird things into their bodies. And so they’re on a tear to banish strange and unfamiliar-sounding ingredients from their lives, the way Marie Kondo might purge a cluttered apartment.

For now, plenty of food companies are happy to oblige them. It’s no secret why: There’s money in it. While sales of “conventional” processed foods have stagnated or fallen in recent years, sales of foods and beverages that boast no artificial ingredients or that claim to be “all natural” continue to rise, despite an often higher sticker price. This growth has been especially strong for foods that combine a clean label with promises of environmental sustainability.

But a question remains: What, exactly, counts as “clean”? Retailers and chain restaurants with clean label programs, such as Whole Foods, Trader Joe’s, Kroger, and Panera, all have slightly different lists of prohibited ingredients. For instance, Whole Foods forbids food containing the artificial sweetener sucralose and synthetic vanillin from being sold in its stores; Trader Joe’s allows both, but bans oxystearin, a waxy preservative that Whole Foods currently permits. Panera’s original “no-no list” of forbidden ingredients included ascorbic acid (aka vitamin C), which it later removed after criticism for promoting pseudoscience.

“‘Clean’ lies in the eyes of the beholder,” Kantha Shelke, PhD, food scientist and principal at Corvus Blue, a food science and research firm, writes in an email. “Also, what is clean today might not be so tomorrow.”

Trust in authorities and institutions is at a low ebb.

That’s not by accident. The definition of “clean” is necessarily murky, because it’s not based on scientific reality so much as subjective perceptions about authenticity and artificiality. In general, consumers seem to feel recognizable ingredients are safer and more wholesome, while additives with chemical-sounding names are undesirable or even dangerous. What determines whether an ingredient is “clean,” then, is not its safety or salubriousness, but how it is perceived: whether it’s foreign-sounding enough to cause a label-scanning shopper to think twice.

As a result, some perfectly benign, tried-and-true food additives have started to become less than welcome.

Take tocopherol. It’s a ubiquitous ingredient in packaged foods like Hershey’s Cookies ‘n’ Crème bars, where it’s added to prevent rancidity and mask off-flavors. To the conscientious label reader, the word might raise eyebrows: It sounds medical and vaguely threatening, like a cousin to formaldehyde or Rohypnol. But tocopherol is nothing but vitamin E—an antioxidant that, by another name, might entice consumers. Vitamin E isn’t nutritious when used this way in chocolate, though it’s certainly safe—and yet the science lab name can be a deterrent anyway.

“It’s one of those internal struggles because it sounds chemical,” Hershey’s master chocolatier Jim St. John told Confectionery News in 2016, as the company debated whether to remove the ingredient from its candy bars. (It hasn’t, but now specifies that it is there “to maintain freshness.”)

Or consider the case of xanthan gum, a versatile stabilizer and thickener produced by fermenting plant-derived sugars. It’s safe and very useful, but to American ears, “xanthan” sounds foreign, like one of the desert planets from Dune—literally, alien. And so it’s become a kind of processed food shibboleth—one that’s spurred continuous debate about what’s “natural” and not. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) currently allows it in organic products, but some consumer groups are challenging food manufacturers’ interpretations of the rules. A class-action lawsuit filed last summer against General Mills alleges that the company’s use of xanthan gum in its “natural” label products is deceptive. And although Whole Foods and other clean label retailers do not forbid it, some food companies like Arla Cream Cheese have decided to remove it in an effort to outdo competitors.

A depiction of xanthan gum in a commercial for Arla Cream Cheese

Removing a safe ingredient because it scares people isn’t exactly a moral victory. But as companies race to streamline their ingredient lists, the label has become a space that can be more about semantics than health.

Consider the conundrum of propylene glycol, a common flavor solvent, which is not considered a clean label ingredient when used as an emulsifier in foods. “Propylene glycol is uber-safe,” says Jennifer Hoffman-Howells, a senior regulatory affairs manager at FONA International, an Illinois flavor company, “and it’s an awesome solvent for flavors, but it’s derived from petroleum.” But its multisyllabic name has scared some manufacturers off, and, for some brands, its use is unacceptable. Strangely, propylene glycol can still make its way into clean label products—just through a back door. On an ingredient label, “natural flavor” can be a sort of black box, enclosing dozens of components, including flavor chemicals, flavor modifiers, and solvents, none of which have to be individually disclosed. Many companies will use additives like propylene glycol when they can disguise them under the benign-sounding catchall “natural flavors”—even if they would reject them as individually listed ingredients.

Words like “natural” create expectations that the realities of commercial food production cannot justify.

Hoffman-Howells—whose work involves translating between consumer perceptions of ingredients, the exigencies of industrial food production, and the finer points of federal regulations—sometimes finds herself troubled by these language games. She worries that words like “natural” create expectations among consumers that the realities of commercial food production cannot justify. Often, she says, “the ‘natural’ label just makes very little sense to me.”

After all, what’s so natural about a plastic jar of hummus made with chickpeas from three countries, blended with oil from combine-harvested commodity crops, and whirred together by automated equipment in a warehouse, sitting on a refrigerated shelf? The simplicity of clean label is an illusion. And yet companies increasingly exert themselves to cater to the American appetite for what is nearly impossible: foods durable enough to withstand modern-day supply chains, in all their length and complexity, made solely with components you’d find in any kitchen cabinet.

Label politics

How did we get here? When did the ingredient label become so fraught, a semantic zone to analyze and argue over?

Xaq Frohlich, assistant professor of history at Auburn University and author of the forthcoming book From Label to Table, a history of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and food labeling, says that for most of the 20th century, much of the information that we take for granted today was not printed on food labels. In fact, FDA opposed almost all nutritional claims on food packaging; these might bamboozle unsophisticated consumers, who should, in any case, seek out professional advice on dietary matters. You probably wouldn’t find ingredients listed on a label either. Under the standards of identity system, only so-called non-standard foods, those which were labeled “imitation,” had to disclose their ingredients. “In practice,” Frolich says, “this meant that the better regulated the product, the less you’d know about it by looking at the label.”

Things began to change in the 1970s, in response to both industry and consumer pressures. The turning point was in 1990, when Congress passed the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act, giving FDA the authority to require nutritional and ingredient disclosures for all packaged foods. The now-familiar “Nutrition Facts” panel—a mandatory, standardized display specifying serving size, total calories, fat grams, and vitamin levels, among other details, with ingredients listed below in order of predominance —did not arrive on the scene until 1993.

Frohlich says that changes to food labeling reflect shifting ideas about consumer capabilities and responsibilities. “Are consumers able to make sense of all this information on their own, or is it better to think of the ordinary consumer as unequipped, as someone who has to be protected from market deceit?” Under the old food standards system, government regulators were gatekeepers, deciding, for instance, whether benzoate of soda belonged in canned tomatoes, and rigidly policing health claims. Our current system mandates greater transparency, but shifts the burden of interpretation onto us. When high fructose corn syrup attracted controversy over its links to obesity, it became our responsibility to read the label and decide whether to accept the risk. Ditto partially hydrogenated oils, artificial colors, and other ingredients sometimes said to be linked to heart disease, cancer, ADHD, dementia, or other ailments.

Marketing language on Sir Kensington’s website

Sir Kensington and NFE

Now, 25 years after FDA’s labeling rules were finalized, there’s more information on food labels than ever. In addition to the nutrition and ingredients panel, packages are also spangled with logos and seals —USDA Organic, Fair Trade Certified, the ringed “GF” of the Gluten Intolerance Group, the blue check-marked fish of the Marine Stewardship Council—as well as many vaguer, less precisely defined claims, such as “all natural.” Despite this glut of information—perhaps even because of it—people feel increasingly uncertain about what they eat. Label-reading can be an exercise in anxiety, a doomed attempt to synthesize the contradictory advice about food and health that filters through news, social media, and friends and family. Often, the apparent transparency of the ingredients label serves to raise more questions than it answers, laying bare all of the things we don’t know about our food. What is sodium benzoate, and what is it doing in my soda? Is organic really worth it? Are GMOs dangerous frankenfoods, or technological triumphs? Is carrageenan safe, or is it an inflammatory toxin that will give me Alzheimer’s? Is turmeric a brain-boosting superfood, or a bitter yellow scam? In an era when trust in authorities and institutions is at a low ebb, many Americans have a difficult time sorting signal from noise and finding answers that feel reliable.

Increasingly, however, we agree about who we don’t believe: big food brands. At the turn of the 20th century, pioneering companies like Heinz and Nabisco invented the idea of branding as a strategy for building trust in the safety and wholesomeness of new factory-made foods, but today most people no longer believe that food companies have their best interests at heart. Millennials and younger consumers, in particular, are reluctant to put their faith in big corporations, shrugging off the brand equity that companies have spent generations building.

“‘Clean’ lies in the eyes of the beholder.”

“Companies are pulling their collective hair out trying to combat this trend,” says Tom Vierhile, innovation insights director at market research firm Global Data. Younger consumers, in particular, “don’t believe the claims” made by legacy brands. “They want companies to prove it.”

A clean label is a proactive strategy for proving it. Most companies describe clean label as part of a commitment to greater transparency. What it is, actually, is an effort to increase comprehensibility. “Simple” is the buzzword, as in Hershey’s commitment to using only “simple ingredients” by 2020, or Frito Lay’s “Simply Cheetos,” cheesy corn puffs “with no artificial flavors or colors to get in the way.” In place of a dense scroll of ingredients with tongue-twisting chemical names, a clean label offers the reassuring presence of familiar ingredients: names you know. The irony is that sustaining this semblance of simplicity requires the very latest advancements in food science, with a futuristic supply chain working overtime.

Getting clean

For grocery shoppers, a clean label might suggest a return to small-scale, even artisanal, methods of production. But minimal labels obscure the huge amount of work that goes on behind the scenes—and clean label goods can require more scientific wizardry to produce, not less. Often, there’s nothing “natural” about them.

For big food companies with legacy brands it can take years of research and development, and major investments in food reformulation trial and error, to take a product clean. Sometimes, it’s an undertaking that requires companies to completely rethink how a food is made. When Unilever relaunched I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter! in 2014, it relied on proprietary “cool blending” technology, developed at a cost of $150 million, to sidestep artificial preservatives and emulsifiers. Many manufacturers have phased out preservatives in fresh or raw foods, such as juices and guacamole, by using high pressure processing, which destroys pathogens without heat.

Reformulating can have consequences up and down the supply chain, from sourcing to distribution. Theresa Cantafio is the co-founder of Go Clean Label, a Chicago consulting firm that advises companies on making the switch. Replacing a chemical emulsifier with a “cleaner” alternative, she says, “might take nine months of lab time, it might increase costs, the lead time on the raw material might be eight weeks longer, there might be certain changes to shelf life.” Getting food to appear less processed—and yet retain the shelf life, flavor, and consistency Americans are used to—requires substantial investments in research and food technology. “It’s really chemistry-driven work, in order to get a product that consumers want, at a cost point and quality that’s acceptable.”

Marketing language on Pipsnack’s popcorn products

Pipsnacks and NFE

Sometimes a “clean” replacement that’s perfect from a functional standpoint will have unpredictable visual or textural changes, sending companies back to the drawing board. Charlie Baggs, president and executive chef of Chicago food product development company Charlie Baggs Culinary Innovations, was recently asked by a major salad dressings manufacturer to produce a xanthan-gum-free version of one of its products. Baggs’ team found a possible replacement: oat bran fiber. “Doesn’t oat bran fiber sound a lot better than xanthan gum?” he asks. The substitute wouldn’t have conferred any additional nutritional benefits, but it was a powerful binder that could duplicate xanthan gum’s stabilizing effects. Unfortunately, it left the formerly lustrous white dressing with a yellow tinge and a grainy texture.

Ultimately, Baggs told me, his team never quite nailed the reformulation, even after 40 or 50 tries. He speculated that if he had been able to source a more highly processed oat bran fiber—one that was bleached and pre-gelatinized, to address the color and texture issues—the ingredient might have worked.

Baggs’ story points to one of the under-acknowledged aspects of going clean: Ingredient manufacturers are at the frontlines of clean label innovation. It’s these businesses—flavor companies, manufacturers of hydrocolloids, emulsifiers, dyes, and other staples of the industrial pantry—that are developing and sourcing ingredients and additives that provide the functionality food manufacturers need, while also satisfying consumer desires for organic or non-GMO sources, or familiar-sounding names. In practice, however, the processed oat bran fiber, or potato starch, or yeast extract listed on an ingredient label can bear very little resemblance to our imagination of those substances. The carrot extract that gives new Twix its orange hue isn’t anything like the juice that dribbles from your Vitamix—and for good reason. It’s highly refined and purified, for stability, consistency, and also safety.

Clean ingredients also don’t make junk food any healthier. Last year, the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI), the non-profit nutrition and food safety advocacy group, published “Clean Labels: Public Relations or Public Health?” an analysis of clean label programs at several major food retailers and restaurant chains. Although the report praised the companies’ leadership in eliminating some worrisome additives, it also notes that they forbid additives that CSPI considers safe. More importantly, none of the programs address what CSPI considers to be the biggest threats to public health in the food supply: added sugar and high sodium levels. Replacing high-fructose corn syrup with cane sugar or agave nectar, or boasting that a product contains “sea salt,” might sound more appealing to consumers, but does nothing to change food’s nutritional profile.

Instead, CSPI recommends companies approach additives in terms of relative risk. Lisa Lefferts, senior scientist at CSPI and author of the report, explains: “We have to meet people where they are, to move them in a healthier direction. While we criticize aspartame and recommend that consumers avoid it, it’s still better than drinking a lot of sugar-sweetened beverages, where we have a lot of evidence of harm.”

The incredible shrinking ingredients list is a stranger phenomenon than it at first appears

Joe Fassler

CSPI also warns that “natural” does not imply safe or healthy. “People buy ‘naturally cured’ meats thinking that they’re healthier, but there’s no evidence for that, and no reason to think that they’re any safer,” Lefferts says. Although naturally cured meats contain no sodium nitrite, the natural nitrates used instead convert to nitrites during processing. In fact, naturally cured meats can have much higher nitrite concentrations. Processed meats, Lefferts says, have been convincingly linked to higher risks of cancer—although “it’s not clear it’s the nitrites, or only the nitrites, that are causing problems.” Still, this concern hasn’t stopped “companies [from] exploiting that misunderstanding” around the word “natural” to sell more luncheon meats.

Maybe this isn’t so surprising. The appeal of clean label relies on a distinction between “real” and “artificial,” as if one was wholly good and the other invariably unhealthy. But the truth is not so clear-cut. Words like “natural” can provide empty reassurances, false promises.

Beyond the ingredients panel

For now, the clean label revolution has mostly been good marketing, a way to seduce eaters by promising all of the conveniences of processed food without the baggage. Ultimately, though, judging sweets and snacks by the familiarity of ingredients—holding them to a kitchen cupboard standard—may not be the most effective way to get what we want out of our food and the system that produces it. If a clean label tells us little about a product’s health impact, what then about the additional factors that matter—food justice and accessibility, environmental impact, and labor conditions? If the spiking demand for natural vanilla is linked to worker exploitation and political unrest, for instance, is it really preferable to synthetic substitutes?

Consumer research has shown that people are more and more concerned with the environmental impact and production conditions of their food choices—especially the younger and wealthier shoppers who are catnip to the food industry. Food companies are increasingly incorporating sustainability and ethics standards into clean label pledges, although these products still comprise only a small, elite segment of the total food market.

Marketing language on Paleonola’s grain-free granola products

Paleonola and NFE

“I don’t think consumers, long-term, are going to continue to be scared of xs and zs” in the name of ingredients, says Hoffman-Howell, of FONA. She hopes that clean label will be increasingly shaped by ethical concerns, considerations about the collective consequences of our food choices, rather than individual worries about particular ingredients. “We all want to make better choices, for ourselves, our families, our world. My hope is that we can eventually get to a place where we can choose artificial on purpose for certain ingredients, because the environmental footprint [of the natural ingredient] is so negative.”

The list of ingredients on a label tells a story, though never the whole story. The larger story is rarely simple: The things we cast as simply bad (like processed foods) or good (like organic agriculture) tend to have both benefits and detriments, and the choices we make usually involve trade-offs. Yet major food companies—and even many small ones—haven’t seemed especially interested in having real debate about the pros and cons. Instead, they’ve settled for congratulating their customers for doing the right thing already.

Clean label still has the opportunity to become what it purports to be right now: a shift towards transparency, increased corporate responsibility, and better values. But to get there will require more than virtue-signaling. The world we should all want—one where sustainable, just, and wholesome food is not only a luxury for well-heeled elites, but a basic expectation for everything we eat—starts with an honest, realistic discussion about how food is grown and made. Let’s hope one day we have the stomach for it.