Roberto (Bear) Guerra/High Country News

The Yaqui catfish was already going extinct. Then came the border wall.

In the spring of 2016, biologists at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service came to a terrible realization: The Yaqui catfish, the only catfish species native to the Western United States, was on the cusp of disappearing. After a week of searching, they could catch only two wild fish. They estimated that, at most, just 30 fish remained.

For approximately two decades, the last known Yaqui catfish in the United States had been kept in artificial ponds built in and around San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge, on the Arizona-Sonora border, and at a local zoo. Creatures of rivers and wetlands, they had not reproduced. Still, federal and state biologists felt they had to try one more time. In a last-ditch breeding effort, the agency gathered 11 fish and shipped them to a hatchery in Kansas. Within weeks, all of them died. Eventually, even the one geriatric catfish left on display at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum had to be put down.

Today, the Yaqui catfish, a whiskery-looking creature that evolved at least 2 million years ago and was once common enough for people to catch for food, is functionally extinct in the United States. There may be a few still hidden in Arizona’s ponds, but not enough to keep a population alive. According to the Fish and Wildlife Service’s 2019 five-year review of the species, it’s on the brink of global extinction; even as the catfish faces ongoing threats in Mexico, scientists don’t know enough about its basic biology to save it.

The fact that a native catfish species existed in such a dry place can be surprising. In reality, prior to European colonization, the region supported rich waterways and aquatic communities.

To people for whom “Sonoran Desert” conjures up images of steadfast saguaros or sun-struck lizards, the fact that a native catfish species existed in such a dry place can be surprising. In reality, prior to European colonization, the region supported rich waterways and aquatic communities. The current extinction crisis speaks to an uncomfortable truth: In a land of finite resources, every choice, big or small — irrigating an alfalfa field, taking a swing on a golf course, burning fossil fuels — means choosing what kinds of habitat exist, even far away from town. And that means choosing which species survive.

Now, the hunt is on to find more Yaqui catfish in Sonora, Mexico. But as the election season ramps up, the Yaqui catfish faces a new threat: The Trump administration is racing to complete the border wall before the 2020 presidential election, blasting desert mountains, tearing up old-growth saguaros and destroying the ancestral homelands and cultural resources of tribal nations such as the Pascua Yaqui, Tohono O’odham and Hopi. According to Laiken Jordahl, a staff member with the Center for Biological Diversity, wall construction will require 700,000 gallons of water each day.

To be clear, the Yaqui catfish is no jaguar. It’s no beauty; it’s not terrifying; its babies aren’t even all that cute. A reclusive fish, it never swam in more than a relatively small portion of U.S. waters. In almost a year of researching them, I still haven’t gotten a glimpse of one. When I lived in Arizona, my favorite catfishes were different species entirely, probably channels or blues; they arrived before me breaded and lightly fried at a small restaurant just south of the University of Arizona campus, accompanied by iced tea, somehow fitting into my convoluted rationalizations about being vegetarian. And yet the Yaqui catfish’s looming extinction bothers me for the simple truth is represents: The Borderlands can’t have its rivers and destroy them, too.

Biologists know surprisingly little

about Yaqui catfish, dusky animals that live at the bottom of ciénegas and streams, growing up to about two feet long. Only about 2% of their historic range lies within the United States; the rest is in Mexico. Living mysterious lives in gloamy places, Yaqui catfish inhabit a world rich in ways we humans can never imagine. Like many catfish, they are covered with tastebuds instead of scales. Catfish are named for the long, flexible barbels that sprout from their faces like a cat’s whiskers, helping them feel and taste their world. Yaqui catfish may communicate with each other through drummings and stridulations, and they may hunt by tracking the electric discharges from other animals’ nervous systems.

Thomas Hafen filters water through eDNA sampling equipment in Cajón Bonito. In a few months’ time he will get the results: Both Yaqui catfish and introduced channel catfish, which hybridize with them, are present.

Roberto (Bear) Guerra/High Country News

The Sonoran Desert’s fishes have evolved fascinating adaptations: Some give birth to live young; others snuggle down and wait out dry spells in the mud. But the past few centuries have been especially rough for them. As the Borderlands’ human communities keep growing, and climate change makes the region hotter and drier, streams stop flowing and wetlands vanish. Meanwhile, introduced species, including channel catfish originally from Central and Eastern North America, push out, or hybridize with, native species. Like most of the Southwest’s aquatic species, Yaqui catfish have struggled to survive since European colonization.

Today, a river in the Southwest often means a dried-out, sandy wash where trash and the skeletal remains of cottonwoods bleach in the sun. But before colonization, networks of riparian areas, wetlands and slow-moving rivers flowed through the region, where Indigenous peoples have lived and farmed for millennia.

A combination of colonialism and human-caused climate change turned rivers and wetlands to dust. Cattle, introduced in the 1500s by the Spanish, overgrazed the land, congregating around and trampling sensitive desert river systems. Farms, mining and the extirpation of beavers all disrupted the Southwest’s rivers, which abruptly channelized in the 1800s, changing from meandering ciénegas to deeply etched arroyos. In the 1900s, enormous dam projects began sending the Southwest’s water far away, irrigating California’s agriculture, even as Sunbelt cities kept growing. By 1973, when the Endangered Species Act passed, such intensive pumping meant that the region’s ciénegas were almost all gone, including the tiny fragment of Yaqui catfish habitat in southeastern Arizona.

Generally, the Endangered Species Act protects critical habitat for rare species, the logic being that a plant or animal can’t survive if there’s nowhere left for it to live. San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge, designated in 1982, was a different approach to saving species. An archipelago of manmade pools in a sea of desert shrubland, the refuge was meant to be a place where native fish species could survive, even as their natural ecosystems drained to sand. The Yaqui catfish lived there, some for decades; what they didn’t do was reproduce. These fish, creatures of deep pools and flowing rivers, seemed to need something that the artificial ponds didn’t provide to breed.

Introduced species, including channel catfish originally from Central and Eastern North America, push out, or hybridize with, native species.

Meanwhile, residents of the Southwest — including me, for approximately half my life — have washed our dishes, cleaned laundry, swum in pools, watered plants, and generally gone about our daily lives by tapping into what water persists, including the Colorado River and underground aquifers. Today in the Sonoran Desert’s dry creekbeds, one can sometimes see a black band in the soil wall — all that remains of miles of rivers and wetlands.

Because only a small part of the Yaqui catfish’s range lies in the United States, American researchers hope that they can collaborate with Mexico to save the species from global extinction, and maybe even donate a few more fish to the United States. But Mexico’s Yaqui catfish, which historically inhabited thousands of miles of river systems throughout Northwest Mexico, are disappearing too, and the race to protect them is hobbled by a basic lack of information.

On the Sonoran Desert’s version of a fall day, the afternoon high hovering around 90 degrees Fahrenheit, a binational group of researchers gathered in Cajón Bonito, a canyon that cuts through former ranchland purchased by a wealthy American, Valer Clark, about a mile south of the U.S.-Mexico border. They were there to collect that missing information.

Emerged from their vehicles, the researchers gathered an assortment of buckets, field gear and notebooks and began walking in the creek, stopping periodically to document its condition. The river clattered through the small canyon, carrying dried leaves above its sandy bed. It also carried evidence of living things that had stepped, swam or sprouted in the water, by way of environmental DNA, or eDNA, fragments of genetic material left like microscopic calling cards. It was these cards that Thomas Hafen, a graduate student at Oklahoma State University, hoped to pick up. As they waded in the river, Hafen and his research assistant, Alex Gutiérrez-Barragán, periodically sampled the river. Wearing medical gloves, they gently scooped water into a filter designed to strain out eDNA. After a battery-powered pump had sucked through enough water, they used forceps to peel the filter out of its cup, carefully fold it up, and place it in a container for shipment to a lab in Montana. In several months’ time, they would know whether any Yaqui catfish had passed by recently.

A combination of colonialism and human-caused climate change turned rivers and wetlands to dust.

A friendly, quiet worker in his mid-20s, with brown hair and a stubbly beard, Hafen spent two years before college on a Latter-day Saints mission trip in Mexico, becoming fluent in Spanish. Now, he was surveying as much of the remaining Yaqui catfish habitat in Mexico as he could for traces of the elusive animals, hoping, eventually, to be able to identify the best habitat for the species. If Yaqui catfish breed in captivity, Hafen’s research will help identify where to release their young, and which rivers to protect.

As Hafen strained water samples, Sonoran Desert fish expert Alejandro Varela-Romero held a bucket and binoculars and peered into a deep, slow pool of green water swirling gently in the lee of a boulder. A thoughtful man in his 50s, with dark hair peppered gray and a mustache, Valera-Romero wore plastic-rimmed glasses and a T-shirt bearing a Spanish translation of the famous quote by evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky: “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” He called out the scientific names of tiny darting fish I could barely see. He had a feeling that a Yaqui catfish might appear.

It certainly was hard to imagine a location more hospitable to native fish than Cajón Bonito, where smoky-black catfish could float gently above the riverbottom, sheltered by sloping banks and submerged branches. Hawks circled overhead, while songbirds called from the bushes. Earlier that day, a skunk had excavated a small dig below a tree stump no more than 10 feet away from where the researchers were working, and then apparently curled up for a nap. But even here, channel catfish — one of the biggest threats to Yaqui catfish — had infiltrated. When Hafen got his eDNA results months later, they would show that almost everywhere in Mexico where he found Yaqui catfish, he’d found channel catfish, too.

“In the past, there were no exotics in the (river) basins,” Varela-Romero explained. “When the (Mexican) government started building reservoirs, federal officers had a brilliant idea of buying exotic fishes like channel catfish and putting them in the reservoirs, to give to the people the opportunity to eat fish,” even though, he said, everyone already ate the native ones.

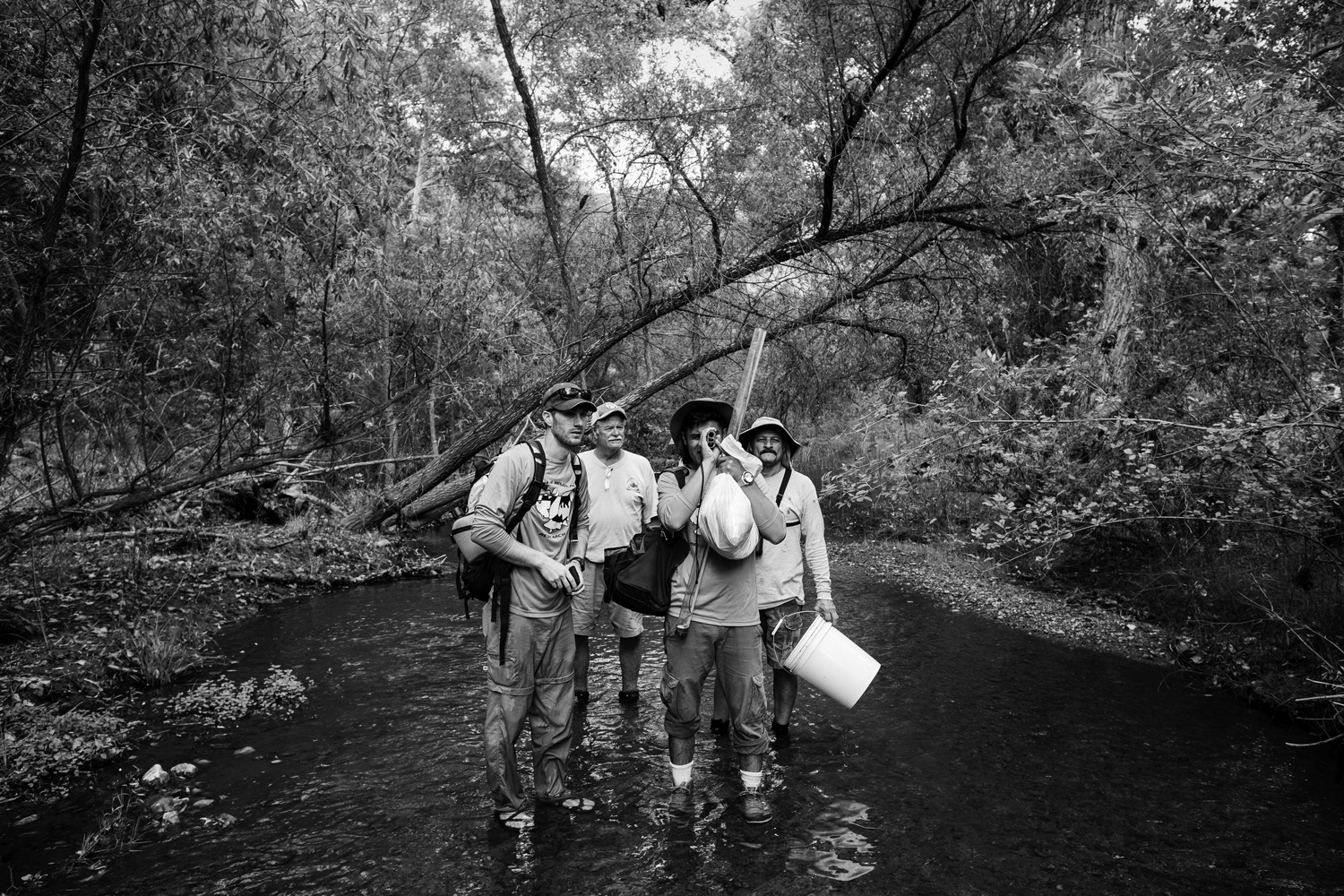

United States biologists Thomas Hafen and Chuck Minckley work with Mexican biologists Alex Gutiérrez-Barragán and Alejandro Varela-Romero (pictured from left) to measure the distance to an eDNA sampling site while conducting fieldwork in northern Sonora, Mexico, in September 2019.

Roberto (Bear) Guerra/High Country News

As these introduced species have pushed the Yaqui catfish to extinction at lower elevations, the species survives higher up, in hard-to-reach, isolated mountain headwaters. There, though, illegal drug grows threaten the fish. Varela-Romero said that in the past, while sampling Sonoran rivers for native fish, he came upon poppies growing wild on the banks. Their seeds had washed down from opium growers.

“The problem is that money from the U.S. pays for those activities,” he observed. The economics can get personal: Varela-Romero’s father’s car was once stolen in Hermosillo, Sonora. It turned up months later in Yuma, Arizona, after being used to run drugs across the border.

Because the Yaqui catfish is dying out, Varela-Romero said, “you develop some kind of love. … We call it cariño en español.” He always got excited when he saw a Yaqui catfish in the wild, wondering each time how many more he might see. Today, though, he had no luck. The catfish, if any were nearby, stayed hidden.

If Hafen and his team represent cutting-edge fisheries research, with fussy portable filters and slick sampling methods, Varela-Romero embodies an older approach to natural history, his expertise earned through hours spent studying different species, counting bent spines, describing the exact color of scales, trying to think like a fish. Another biologist on the trip, Chuck Minckley, was an original member of the Desert Fishes Council, a nonprofit research organization for desert fish biologists in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands. Minckley missed the first meeting because he was drafted for military service in the Vietnam War, but he hasn’t missed one since. Now in his 70s, he waded slowly down the canyon as Hafen’s crew sampled the water, pausing to rest at times on an overturned bucket. His ancient black Lab, Shadow, raced happily through the shallows, huffing like a freight train.

Varela-Romero and Minckley are determined to catch and breed Yaqui catfish in Mexico as quickly as possible, even though no one really knows how. It’s easy to read their efforts as a comedy of errors, with fish found, lost, misidentified. In reality, with low budgets and improvised tools, the researchers are learning how to work with the species. The problem is that their learning curve has crashed into an extinction curve. After years of neglect, the Yaqui catfish is rare enough that every fish matters, making it hard to experiment with ways to breed them, or even to keep them alive.

After years of neglect, the Yaqui catfish is rare enough that every fish matters, making it hard to experiment with ways to breed them, or even to keep them alive.

One afternoon in Mexico, the researchers attempted to recover eight Yaqui catfish caught in Cajón Bonito, which had escaped from some netting in a holding pond. This involved using a broken kayak paddle to maneuver a rowboat, which Minckley had purchased as a teenager to take duck hunting, out to the middle of the pond, and pulling up yards of soggy netting.

The men excitedly hauled a catfish to shore in a bucket and gently transferred it to a shallow rectangular container. The small, soot-gray animal burrowed into the corners, seeking an escape with its mouth and barbels. We crowded over it, and I found myself getting unexpectedly emotional, looking at what might be one of the last of an under-studied, barely known species, trying to escape from a plastic box. I felt foolish a few minutes later, when Varela-Romero checked its pit tag and announced that it was actually a Yaqui-channel hybrid. I wondered whether the loss of a species that looked just like one of the most common fish species on the planet really mattered.

Only later did it occur to me that perhaps, if I couldn’t tell the difference between a Yaqui catfish and a channel catfish, that was because they communicate in the language of fish, not primates — that their seeming interchangeability said more about my limited understanding than it did about their limited distinctions.

The same economic pressures that push Yaqui catfish toward extinction today have wreaked havoc on local human communities for centuries. Even as American and Mexican researchers try to save the species, tribal nations such as the Pascua Yaqui are working to re-establish control over their natural resources, including the Yaqui catfish.

Even as American and Mexican researchers try to save the species, tribal nations such as the Pascua Yaqui are working to re-establish control over their natural resources, including the Yaqui catfish.

“If we had a tapestry of our history on this side of the border, it would probably be missing a bunch of big chunks,” Robert Valencia, then-chairman (now vice chairman) of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, told me. Valencia and I met in a conference room at the Pascua Yaqui Tribe’s administrative offices, about 20 minutes away from downtown Tucson. Valencia, who is in his 60s, has dark hair and a thick salt-and-pepper mustache. He wore what he called his “end of summer” shirt — a red Hawaiian-print button-down. To Valencia, the tribe’s history is too important to lose. “We can’t let things go,” he said. “As a matter of fact, we’re doing the opposite. We’re looking at — on both sides of the border — what are important parts of history we don’t know, or we need to know more?”

At one point, Valencia wrote down a Yaqui word for me in my notebook, after I struggled to sound it out myself. “What it means is, ‘In the beginning,’ ” he explained. “We have to always remember what we had in the beginning. To me, that’s number one.”

To Valencia, the catfish ties Yaqui peoples to the Río Yaqui region, in part by embodying the importance of water to the tribes. As the flow of Borderlands water and species has been curtailed, so, too, has the movement of Yaqui peoples across their ancestral lands.

“If we had a tapestry of our history on this side of the border, it would probably be missing a bunch of big chunks.”

Considered Mexican by the United States, the Pascua Yaqui Tribe only gained federal recognition in 1978, despite its presence on both sides of the border since long before the United States or Mexico existed. In 1964, the tribe secured the land in southern Arizona that would become its reservation from the Bureau of Land Management, after surviving the Yaqui Wars, a persistent attempt — first by the Spanish government and more recently by Mexico — to kill off Yaqui tribes and use their land along the Río Yaqui for mining and large scale agriculture. “If you read about our history, there was an unwritten extermination policy against our people in Río Yaqui,” Valencia said. “They killed us, shipped us off as slaves in Yucatán, did whatever they could.” People were sent as far away as the Caribbean and Morocco, never to return.

In the late 1970s, Valencia’s uncle, who was tribal chairman, successfully fought to gain tribal recognition from the U.S. government. Today, the Pascua Yaqui Reservation includes approximately 2,000 acres southwest of Tucson, bordered partly by Tohono O’odham land and partly by the city’s growing sprawl. Yaqui people regularly move back and forth across the U.S.-Mexico border, although that’s been harder since the 9/11 terror attacks, Valencia said. Valencia’s mother, who was born in the U.S., grew up in the Yaqui pueblo of Tórim in Mexico. Valencia remembers her reminiscing about rivers “teeming with fish,” before Mexico built three dams along the Río Yaqui.

On the one hand, the delayed recognition of its sovereignty means the tribe is only now addressing quality-of-life issues that go back decades, Valencia said. But he sees advantages to its independence from the federal government. “Because we weren’t entrenched, we don’t have federal programs that are based here; we didn’t want any,” Valencia said. “We always insist on directing whatever effort it is, whether research, whether programs, because what we found over the years, if we let other people do things for us — it fails, every single instance.” Yaqui catfish conservation seems to fit this pattern: In 2015, after three years of applications, Valencia won a grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to create monitoring and educational programs about Río Yaqui fish on both sides of the U.S-Mexico border. Not long after, he found out about the 2016 die-off of Yaqui catfish at the Kansas fish hatchery.

Roberto (Bear) Guerra/High Country News

Using a boat Chuck Minckley has owned since he was a teenager, he and Thomas Hafen check netting for Yaqui catfish that escaped into a holding pond at Rancho San Bernardino in Sonora, Mexico.

Working with the eight Yaqui pueblos in Mexico, Valencia wants to create family-based “microhatcheries.” Partly, this is for cultural reasons — the Yaqui catfish is a traditional food — but it would also be part of the Yaqui pueblos’ long battle for the Mexican government to honor their treaty rights, which include extensive control of water and other natural resource in the Río Yaqui basin. Currently, Mexico’s dams force Yaqui communities in Mexico to rely on water contaminated by agricultural runoff laden with pesticides and heavy metals. According to the Latin American Herald Tribune, Mexico defied its own Supreme Court to build an aqueduct to pipe Río Yaqui water to Sonora’s growing capital city of Hermosillo, further ignoring Indigenous claims to the watershed and its natural resources, including its fish.

The Pascua Yaqui Tribe has already built microhatchery prototypes. One sunny morning in September, I met James Hopkins (Algonquin and Métis), a law professor at the University of Arizona who directs the Yaqui Human Rights Project Clinic and has legally represented Yaqui pueblos in Mexico, in a parking lot near the Pascua Yaqui Tribe’s Casino del Sol. On roads made slick and puddled by recent rain, we drove together to Tortuga Ranch, a former cattle ranch that the tribe now owns, to examine its prototype aquaponics operations. A hoop house held burbling tanks where luminous koi fish swirled under bright green vegetation. Further efforts to raise Yaqui catfish were on hold for now, until more Yaqui catfish become available. But even without the catfish, microhatcheries of fish such as tilapia or channel catfish could be important routes to nutritional independence for Yaqui families in Mexico.

“(Yaqui pueblos) want a clean, sustainable protein source,” Hopkins said. “There’s a huge infant mortality rate (in Mexico), primarily because all their protein from the local area — fish, dairy from local cows, goats, pigs — is going to be carrying persistent chemicals, mainly DDT.”

“Anything you’re trying to return back to nature, your plan has to fit with the larger state plan.”

On the U.S. side of the border, Valencia would like the Pascua Yaqui Tribe to raise Yaqui catfish in captivity, in part for a commercial market. “It’s one of those things I think can be successful,” he said. “The people have some knowledge of the species itself.” Hopkins, though, expressed a more cynical reason for growing Yaqui catfish in microhatcheries. “Anything you’re trying to return back to nature, your plan has to fit with the larger state plan,” Hopkins said. For Arizona to take interest in the Yaqui catfish, there had to be a commercial value, such as a restaurant market for the fish, or an interest in sport fishing.

“I’ve been transparent with people like Chuck Minckley and others, saying, ‘Look, if you bring the fish back, where’s it going to go?’ ” Hopkins told me. “It’s going to have to be a commodity in its own way.”

One warm fall day last September, I visited San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge, a remote landscape of rolling hills with a backdrop of sharply angled mountains at the Río Yaqui headwaters in southeastern Arizona, where the last Yaqui catfish in the U.S. were caught for the failed breeding effort. Traces of catfish eDNA still turn up in ponds here, although it’s uncertain whether that DNA is from living fish, or the remains of dead ones. This is where the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service would like to reintroduce Yaqui catfish, if Mexico agrees. Up close, the ponds seemed peaceful: small, cattail-ringed pools rippling in a rising breeze.

But now, the ponds themselves are endangered, collateral damage in the Trump administration’s determination to construct a border wall before the November election. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, wall construction continues at a breakneck pace, using local water to spray down dusty roads and mix concrete. As of this writing, Customs and Border Protection has not provided High Country News with requested groundwater use estimates.

“What’s that adage about how far you can lean off a cliff before you fall? You don’t know until you lean too far.”

According to Myles Traphagen, a field biologist and GIS specialist who previously worked at San Bernardino, no environmental analysis has been conducted on the impacts of wall construction on the region’s water, or on its fish. “Since there was no NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act review) required, no prior studies, we are essentially navigating in uncharted territory, with no baseline for what the final effects might be,” Traphagen said. Refuge staff declined to comment on the impacts of the border wall.

On my drive back to Tucson, the clouds gathered into a gray comforter, trailing rain far to the south. It was my favorite kind of dappled desert weather, the filtered light deepening the green on hillsides and softening the craggy mountains. In the distance I spotted a bright white post — a historic border marker, rising from the shrubs. Past that, the roof of a ranch house in Mexico. Trucks passed me slowly on the dirt road, spraying water to keep down the dust. It took me a few minutes to realize why: They were preparing for the construction crews to arrive, to build the border wall. Perhaps the next time I drove through, those mountain views would be gone. So, too, might the springs that the refuge’s fishes relied on. Without water, there would be no future here for the Yaqui catfish.

I later called Bill Radke, who has managed San Bernardino for about two decades, and asked him whether falling groundwater levels in the refuge might be just one more threat to the Yaqui catfish, or the final nail in its fishy coffin. Radke would not comment on the effects of the border wall construction, but he acknowledged that groundwater levels have always been a big concern for the survival of fish at the parched refuge.

“You almost have to end your story that way, because I don’t know that any of us can say that for sure,” Radke said. “What’s that adage about how far you can lean off a cliff before you fall? You don’t know until you lean too far.”