Instacart

On Wednesday, California Governor Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill 5 (AB5), a groundbreaking piece of legislation designed to make app-based companies start treating their workers like real employees.

The question now is whether any of them will do so without a fight.

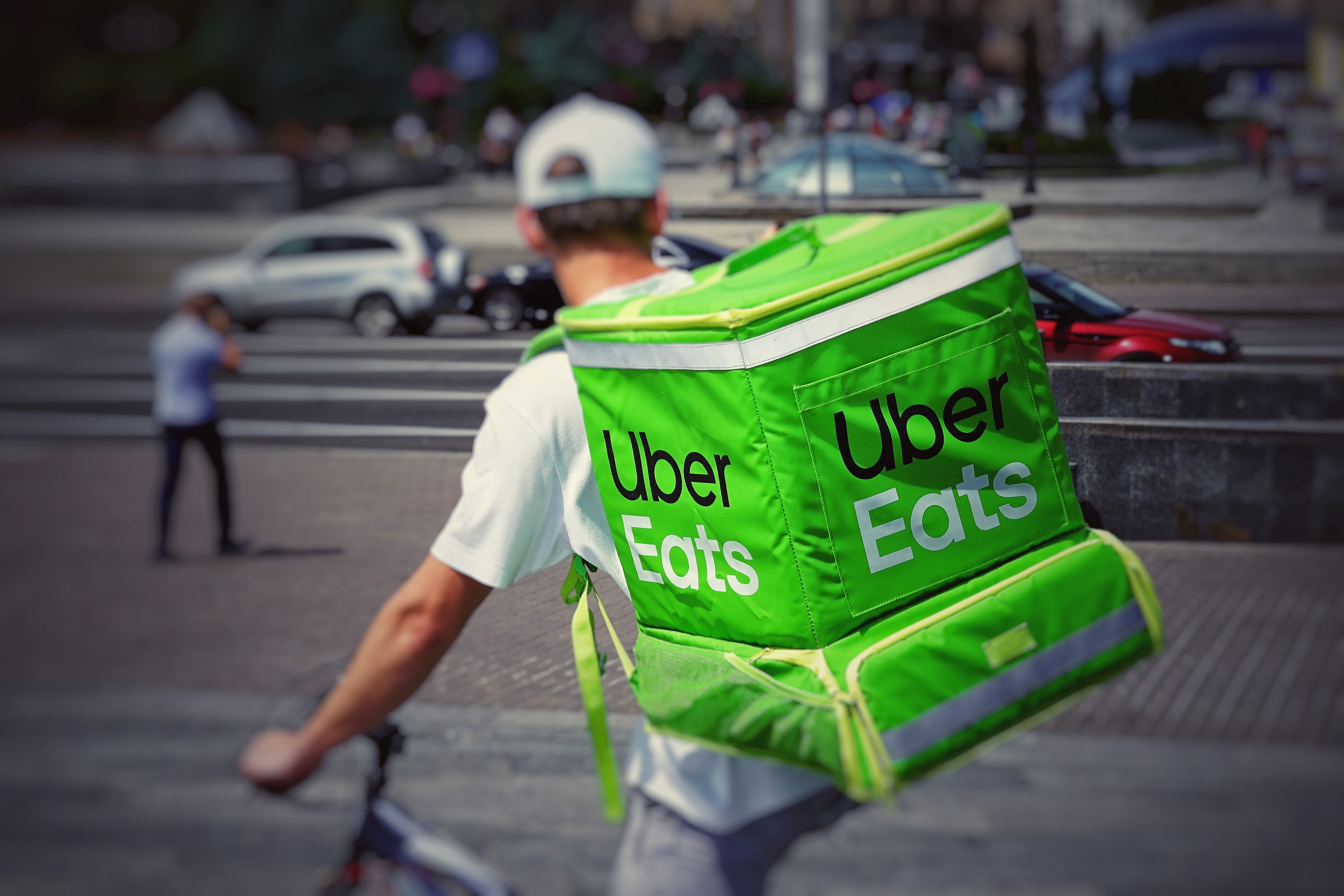

Food delivery companies, just like rideshare companies Uber and Lyft, often rely on independent contractors to pick up food from restaurants and grocery stores and carry it to customers’ homes. In the past, they’ve tried to sell this setup as worker-friendly (freedom! flexibility!), but workers have organized and argued that they don’t actually come out on top. There’s mounting evidence to back up their claims: In February, a labor group claimed that half of Instacart’s drivers earn less than minimum wage, and a prior DoorDash policy counted workers’ tips against the minimum guaranteed payment. Assembly Bill 5 (AB5) is intended to force companies to classify some contractors as employees, enshrining their rights to key benefits like the minimum wage and the ability to unionize. The bill codifies a recent state Supreme Court decision.

But the independent contractor setup is baked into the business model of many of the tech companies affected by AB5. After all, having real employees can get expensive. You’re on the hook for a share of Social Security and Medicare. If you have more than 50 employees, you’re required to offer health insurance and pay for more than half of it. Industry players aren’t exactly welcoming this policy change with open arms.

In fact, Uber has already made the interesting claim that drivers aren’t core to its business, and therefore the new rules don’t apply. Lyft, Uber, and DoorDash have vowed to spend a combined $90 million to oppose the new rules.

So what does this mean for the people who deliver food in California?

We asked some of the big delivery companies (Grubhub, Caviar, Instacart, etc.) if they planned to reclassify their couriers as employees. Most didn’t respond.

Instacart issued a statement saying its couriers “choose to use the platform as shoppers so that they can have access to independent, flexible work that fits around their lives.” The company adds that “Unfortunately, AB5 missed the mark and offers a one size fits all solution that we believe is a disservice to millions of Californians.” The company is committed to finding a “better solution.”

Grubhub has been largely silent on the issue, though Nation’s Restaurant News reported that unlike Postmates or DoorDash, the company’s business model is not solely reliant on independent contractors. About two-thirds of deliveries on the platform are carried out by drivers employed by its restaurant clients.

Delivery.com told us it was not interested in getting involved with this story.

Postmates CEO Bastian Lehmann wrote in a July op-ed that gig workers should make minimum wage, have the option to enroll in healthcare through some kind of “industry-wide benefits fund,” and should have a voice through worker forums, which presumably fall short of unions.

If it sounds like a watered-down version of full employee status, that’s basically what it is. Uber and Lyft, too, have been pushing for something similar: Uber has offered to guarantee minimum earnings and provide “portable benefits” in California. It’s worth noting that New York City recently passed a $17 minimum wage requirement for rideshare drivers, much like what the company is offering as a bargaining chip in California, and Uber and Lyft responded by blocking drivers from the app while demand is low, effectively clocking them out by force.

It remains to be seen whether or not other states follow California’s effort to regulate the gig economy, and whether platforms that rely on cheap labor will survive the transition. What’s becoming clear now is that the platforms won’t make a change without a fight.