Adam Kuehl

In 2013, a New York businessman named John O. Morisano embarked on an improbable venture: He bought a historic, once-segregated bus station in his adopted hometown of Savannah, Georgia, and, without a soupçon of hospitality experience, decided to open a restaurant.

That wasn’t all. He also wanted to enlist a Black woman chef—any Black woman chef, one he hadn’t found yet—to help make meaning out of the eatery he envisioned building in one of the South’s oldest cities.

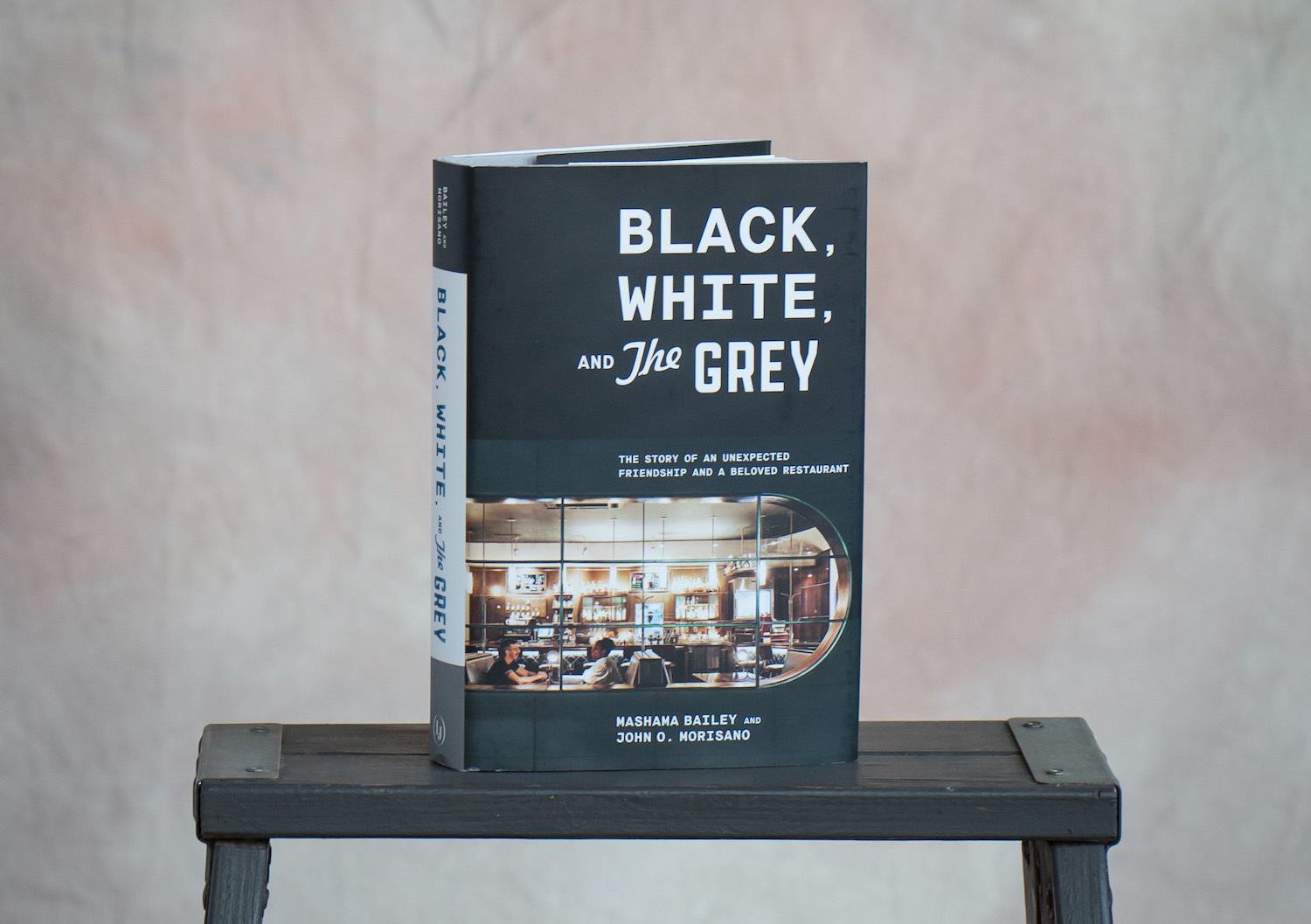

In the recently released book, Black, White, and The Grey: The Story of an Unexpected Friendship and a Beloved Restaurant, “Johno” Morisano and co-author Mashama Bailey—the executive chef he ultimately asked to be his business partner—explore the unusual history of their acclaimed Savannah restaurant, The Grey. But it’s more than a “making of.” The book’s primary subject is the emerging, often uncomfortable relationship between the two principals: Bailey, a Black woman chef with Georgia-New York roots and a yen for a new professional challenge, and Morisano, a wealthy Italian-American entrepreneur who wants you to know that he grew up working class. She has decades of industry experience. He knows virtually nothing about how to run a functioning restaurant, though he admits he’d “wanted to be congratulated” for bringing his concept to Savannah, a place married to rigorous worship of the past, if not rigorous racial reckoning.

Ten Speed Press

In format, Black, White, and The Grey alternates between Morisano’s musings in plain font and Bailey’s in bold, black typeface, a split screen of a shared experience. Morisano wrote a first draft of the book—but, after publisher feedback that it badly needed Bailey’s voice, the pair spent more than a month in Paris, rewriting it line by painstaking line. The result is a deceptively low-key book that nonetheless bristles with the tensions of a relationship unfolding across lines of race, gender, and communication. Black, White, and The Grey swings between radical transparency and extreme restraint, with Johno cataloging his own blunders and Bailey sometimes quietly checking his assumptions.

Counter senior editor Cynthia Greenlee had a conversation about the book with friends, including fellow journalist Christine Grimaldi, who often writes about the politics of Italian Americans. Below, the two expand upon that conversation in a tandem review that mimics the book’s organizing principle of dual voices telling their stories, sometimes paragraph by paragraph.

Cynthia R. Greenlee: I wasn’t sure whether to shake restaurateur John “Johno” Morisano—or shake his hand. This book is a story of his desire to do something particularly ill-advised: start a restaurant because he loves his Italian grandmother’s “gravy,” the pleasure of food, and wants to do something transformative. He didn’t know that there’s an actual process to figuring out how many seats a restaurant can hold, beyond the spatial limitations of square footage.

Entrepreneurship requires audacious belief in one’s self and a project, and there’s a vulnerability in so thoroughly reporting one’s own ignorance about restaurant creation and race. It’s both admirable and galling, as is his insistence that he will collaborate with a Black woman executive chef. He interviews a procession of white tattooed kitchen dudes for the spot as his co-pilot. When none of them works, he changes course and picks a demographic—not a specific person—for his future collaborator.

I struggled to think of comparable books that follow a white male-Black woman relationship based on mutual respect, food, and labor. The late Edna Lewis published The Gift of Southern Cooking with fellow chef Scott Peacock. That was a different book—given her age and indisputable stature, and his status as her protégé and friend. But I wonder what models we have for healthy interracial collaboration in food—and beyond—and what models we have for publishing that centers Black women in those partnerships.

Christine Grimaldi: Though not food-centric, Ann Friedman and Aminatou Sow’s Big Friendship: How We Keep Each Other Close recounts their interracial friendship and business partnership for their popular podcast “Call Your Girlfriend.” The two share a gender and sometimes a voice, writing parts of the book in the first-person “we.”

Johno and Mashama did not start out as friends or relative equals as Friedman and Sow did. They never use a unitary “we.”

About 50 pages into the book, Johno writes, “I don’t know who the chef is, but I know who the chef should be … a Black woman.” While Black women comprise a tiny percentage of chefs in this country’s fine dining establishments and Johno is opening the door for a Black woman chef, it’s on his terms. I feel like there’s a bit of a “magical Negro” trope at play here, where he expects not just himself, but the whole of Savannah, to be changed by this Black woman chef and their collaboration.

Cynthia: Just a word here about the magical Negro: It’s a pretty lamentable device often used in literature and film, by which a Black character pops up and becomes the vehicle for a white character’s epiphany or life change through that Black person’s suffering, unnatural wisdom, death, or some combination thereof. Think the character John Coffey in Stephen King’s The Green Mile.

Christine: Or the 2019 Academy Award darling and Best Picture winner Green Book, which reimagines renowned Black pianist Donald Shirley’s life as a vehicle for his white Italian-American chauffeur’s redemption on a tour through the South—Shirley’s family saw the movie for what it was.

Johno’s own language helps make the case: He literally writes that “if she can cook Italian, I feel like she would be the Holy Grail.” Mashama’s response to that “ridiculous” conversation he’s having with two New York City-based restaurant designers: “Three White men talking about finding a Black woman chef as though she’s a unicorn of some sort, a mystical creature with talents that could only be dreamed of.”

The Grey was a once-segregated bus station, now turned restaurant, in Savannah, Georgia.

Cynthia: I hate “magical Negro” tropes—because white people benefit from Black tragedy and labor. And because Mashama didn’t just show up and add #BlackGirlMagic. We see how much she’s working and trying to figure it out. Yet … I don’t disagree with you. He needs her to prove his credentials as a “good white man” and to lend credence to this restaurant-as-racial-redemption scheme. To write this book, even. She makes clear she’s a reluctant partner in this book project at first. But I winced when you used that language here because—clearly, this book has me in my feelings and the objective reviewer is largely a fictional being—I don’t want to reduce Mashama to that.

Christine: Neither do I. She has way more agency and repeatedly asserts it in her passages.

Cynthia: And her sweat equity asserts it. But she can have agency and still be at a disadvantage in this relationship. And she may not speak as much, but let’s not mistake that for silence or passivity. There is agency in the strategic decision to let some things go, to circle back later, or do what you need to do at your own pace. And maybe that’s part of the pattern she and Johno have established.

Christine: Maybe she’s trying to avoid being seen as the Angry Black Woman. Though women are socialized to be unfailingly nice, white women can break the mold with impunity or even reward. Whereas Black women face consequences for their anger.

Cynthia: Memoirists don’t owe us all of themselves, but I did wish I saw more anger from Mashama. It’s there, in a few places, because anger is human. What I wonder is: How much intention is in her silence? As she said in a joint Food & Wine interview with Johno: “If you want to know why people act the way they do, you have to read behind the lines.” Hard to know exactly how much interstitial reading the authors want us to do. Silence can mean agreement, an avoidance of conflict, or a deferral of difficult discussions.

I’m also deeply doubtful that restaurants can be social experiments or disruptors that help us reframe history or a better future, though they can by paying living wages and so on. I can see Johno’s vision of The Grey—making this building haunted by segregation into a beautiful meeting place. As a historian (and an African-Americanist historian specifically), Black Southerner, and human being, I get the symbolism. I was moved when Mashama sees the old powder room for white women in the building and feels the weight of that space. And I love a good restaurant story (though I love the food more).

But as a Southerner, I just have to say, with both snark and truth, it always seems to be New Yorkers who want to come to the South to fix it. The South is the most obvious site of Black subjugation in the country, but it’s not the capital of American inequality. Outsider perspective is important, and I don’t want to parrot Southern white supremacists who have been crying “outside agitators are stirring up trouble” since the Civil War and throughout the civil rights movement. But I have to wonder why he decided on this project of Southern improvement when he says so eloquently, “I did not know jack-shit about the South or its social and cultural complexities—the benign ones or the malignant ones.”

Christine: Right. It’s worth asking, then: Why did Johno insist on opening this restaurant in the South?

Cynthia: Good question. Cheaper? It’s a place he loves? Readily accessible narratives about racism? Probably all of the above. And Mashama has to learn the South, too, though she spent part of her childhood there. And that’s a different migration and learning process for many Black Americans reared in the North, often with family stories of fleeing the South due to racial oppression and hardship.

It’s impossible for me not to read this dual account without pondering two narratives that ruled the end of last year and the beginning of this one: the toxic masculinity of white men in politics and how Black women in the South saved the day by organizing for elections, ostensibly “for our democracy.” I vacillate between thinking I want white allies, businesspeople, and decisionmakers to be vocal champions about real diversity and cringing at how Johno does it—or at least explains it. Though this book is jointly written, we get a lot of Johno figuring how much he doesn’t know, and his mounting anxiety as bills start to climb.

Much of the book left me thinking about who gets support for professional wild-goose chases. Johno barely mentions previous business ventures. While we see Mashama through the lens of his assessing gaze and her qualifications, he doesn’t provide a vita. He’s got the idea, shoulders much of the material risk, and must come off as a bankable risk. He possesses all these things because he has wealth, maleness, business knowhow, contacts, and probably what a Mexican-American friend of ours calls “good white credit.” Whiteness is currency.

Christine: I spent the first 12 years of my life in Johno’s hometown—Staten Island, long the whitest and most conservative borough of New York City. Racism there wasn’t “disguised in a classy suit,” as Mashama writes of the North; it wore police uniforms and construction vests. Still, I identified with Johno’s assessment of his working-class Italian-American family: “We fantasized about what life would be like with a job that wasn’t blue collar, one where the only gunk on your hands was ink from a pen.” The gunk on my parents’ hands was dry-cleaning chemicals that stripped them raw while I typed on a keyboard. But I’ve also witnessed the white working class seethe with grievances, real and imagined, punching down instead of forging interracial solidarity.

As a product of this environment, I absorbed casual racism like a sponge and am still wringing it out of my brain, all these years later. How can readers assess Johno’s growth, or lack thereof, if we don’t really know his origin story beyond mostly idealized scenes over Sunday gravy? I appreciate Johno’s honesty about his internalized racism and inherent biases, but he’s often narrating instead of analyzing them and their role in The Grey.

Both Johno and Mashama have faith that I lack in the power of a shared meal. During the Trump administration, the same officials responsible for separating families at the U.S.-Mexico border by day dined at Mexican restaurants by night. I just don’t believe that breaking bread is all that revelatory and redemptive. I wish I did.

Johno cooked not one but two meals to make amends for fits of bad temper. Mashama wasn’t a fan of Johno’s carbonara, and neither was I, based on its description. (Who puts chicken stock in carbonara?) Meanwhile, I can’t wait to try Mashama’s end-of-chapter carbonara recipe from The Grey’s menu. Johno kept trying to push Mashama into Italian cuisine, and while she can outcook him, she shouldn’t be confined by the limits of his restaurant experience and white imagination.

I had to laugh when Mashama said the only things she knew about Staten Island were the mafia and Wu-Tang Clan.

Black, White, and The Grey: The Story of an Unexpected Friendship and a Beloved Restaurant explores the unusual history of Mashama Bailey and John O. Morisano’s acclaimed Savannah restaurant, The Grey.

Photography by Chia Chong

Cynthia: I appreciated that because it shows that Mashama doesn’t live in Johno’s narrative bubble. His nostalgia and history are not hers. But they also don’t have to be her marching orders: His micro-manipulations trying to get her to make The Grey into an Italian concept were obvious, and I’m glad they didn’t work.

Mashama’s voice does so much work in this book: offering counterpoints, context, punctuation. And, frankly, it’s a palate cleanser. She’s measured where Johno rambles, which may be as much a function of personality as it is writing style or the fact that she’s often positioned as the “respondent.”

It also doesn’t escape me how difficult it is to have a real conversation about race as a Black woman with a white man, and I’m not even talking about situations where money, livelihoods, and futures are involved. In the last several years, I made a rule to not talk about race with white people—with the exception of a few like you, Christine. I’ve often been hit in the face by the unthinking racism and ignorance of white people I’ve thought of as more than passing acquaintances—to the point that I’ve pretty frequently asked myself if white people and Black people in America can truly be friends. The rank racism and disparities of American life mean I’m always going to be less safe than you are.

Though did you read their relationship as a friendship? And does it matter? Plenty of business partners don’t have to be friends, though partnership is a kind of transactional intimacy. For most of the book, Mashama seems to be waltzing with someone she’s not yet sure she wants to dance with.

Christine: Johno thinks they’re friends. He feels like he personally disappoints Mashama when a racist patron’s remarks render him speechless. Mashama, in the middle of a busy dinner service, is neither surprised by nor receptive to Johno’s white guilt. “So what?” she seems to be saying. I’ve gotten that vibe from you on occasion, Cynthia, when I’ve shared my anxiety over if and how to talk to certain racist relatives, and rightfully so. To me, Johno and Mashama’s friendship status depends on his ability to understand her reaction. True friends share problems, not burdens, especially in an interracial friendship.

Cynthia: I’ve thought about whether I did you a disservice in responding that way when you talked to me about racist relatives. I settled on this: I can’t worry about how white people deal with racism within themselves or their families, though white people need to have those discussions among themselves. I can’t spend my time fretting about white people or what they think about me, but—and this is going to sound contradictory—I do have to worry about your relatives when I meet them in various settings or on the street, particularly streets they consider theirs.

Christine: That’s a valid concern. No matter the kind of discussion, in person, in writing, or both, the project of white improvement isn’t the point. The point is preventing the next BBQ Becky from actions that cause harmful—even deadly—consequences for Black people.

I thought about this in relation to Johno’s police officer brothers. Johno does meet Mashama’s family and dines with them. Does he ever bring Mashama home to New York to meet his family (besides his wife)? Would she receive a warm welcome from the cops in his family? Regarding the scene of a fatal car accident that killed The Grey’s top general manager, Mashama writes that “good policing is a gift.” That’s generous, when policing typically offers Black people little to no grace.

To me, the book’s biggest failing is its complete detachment from the political-cultural backdrop against which its events, from 2014-2020, occur: the postracial myth of Barack Obama’s presidency, the surge in police killings of Black people, the white supremacist backlash in the form of Donald Trump’s election, and the Black Lives Matter movement. Johno’s only nod to Trump is when he bemoans a rise in “nationalism,” toward the end of the book. What color is that nationalism, Johno?

The book’s epilogue addresses Covid-19 but not police brutality—this country’s pandemic of racism is begging to be addressed, too, especially in a memoir about an interracial partnership and business located alongside a historically Black, low-income part of Savannah. Their relationship, to me for most of the book, is captured by the statement Mashama makes early on: “Three years into our partnership and I only called Johno when I had to.”

Cynthia: Well, don’t you see why? He loses his mind when she takes time off for her birthday and her sister’s wedding. To be fair, it’s a critical time for the restaurant and shows what a pressure cooker the world of hospitality is. But we get to see both his and her thoughts and actions here—which is gripping and infuriating. He resents her time off, but can’t say that. Yet he also can’t stop himself from stomping around while offering her friends restaurant swag (as a person who sometimes gets in my own way, I sympathize). He fears her lack of commitment and steps perilously near to suggesting that her work ethic is suspect. I really thought this would be Mashama’s WTF moment.

Christine: I’m trying to judge the memoir and not the memorists, the writing and not the people, but it’s really hard not to judge Johno for that and bringing his gun to the accident scene.

Cynthia: For me, the big omission is details about the terms of their partnership. Confidentiality matters and plays a role in this, I’m sure. But you can’t talk about racial equity without economic or workplace equity. And I’m talking about LITERAL equity. Call me nosy, but I wanted to know more about their partnership. Many restaurateurs don’t want to partner with chefs at all. How big of an owner is Mashama? What kind of decision-making power does she have? As executive chef, she’s far more than a cook for hire. But in a country built on Black labor and captivity, I want her to have a good chunk of that business. It’s pretty clear to me that Johno and Mashama had very different concepts of how their relationship was going to work.

Christine: The book is mostly about the beginning of their partnership, the building of the restaurant. If that’s often difficult, what does running The Grey look like?

Johno’s statement that he’s looking for a partner “who would be completely in it with me and not just on board for a paycheck” reminded me of every bad boss I’ve ever had. A job is a job because you can leave it at the end of the day and go home to your real family. The fight over Mashama’s birthday is so uncomfortable because Johno is acting overfamiliar, like she’s a child he can scold. But here’s a place where Mashama delivers one of her most pointed rejoinders of the book: “Stay the hell away from this, businesspeople. … your restaurant ‘family’ consists of people you will have been in the trenches of service with but who in many ways are no substitute for your true family, who loves you unconditionally.”

Cynthia: Familial metaphors are dangerous, especially in the world of work.

Christine: I felt uncomfortable when Johno calls Mashama “sister” over his apology pasta carbonara. What parts of Mashama does she need to silence or sacrifice to seize hold of this complicated opportunity?

Cynthia: It seems that Johno and Mashama DO connect over grandmother stories, the shanks those women would cook. I’m not comparing Johno to a slaveholder here, so don’t get it twisted. But how many times have I seen slaveholders say in letters from the 19th century that enslaved people were “like family”? In the early 20th century, textile mill owners who subjected their poor white employees to harsh working conditions—dangerous machinery, child labor, factories with poor ventilation and little sunshine, poverty wages—said their workforce was like children who had to be trained and forced into routines. The boss was the great benevolent father. Except he was paying you and not much.

Christine: Mashama notes that after reading Johno’s first draft, she knew she had to take a stronger role in the book: “Generally speaking, the White audience thought it was great, smart, and interesting. The Black and Brown audience thought my voice was dull, marginalized, and weak.” I think Mashama’s voice is the strongest, most insightful component of the book and yet it’s still marginalized by the amount of space that Johno quite literally takes up. He’s honest about his shortcomings, but they’re still shortcomings.

So all these questions aside, is Black, White, and The Grey worthwhile because it’s led to this conversation? We can’t stop talking about it, in ways I believe are constructive. I could see white readers glossing over Mashama’s truths and buying into a fairy tale of a restaurant and a book.

Cynthia: We live in a segregated society, even though de jure Jim Crow is gone. I recently read somewhere that “people find themselves in the stories of others.” We can read that multiple ways: Do we just find the things we already agree with or relate to? Or do we find new possibilities for who we can be?