This week, two of New York City’s most powerful restaurateurs have taken leave of their empires over allegations of sexual misconduct.

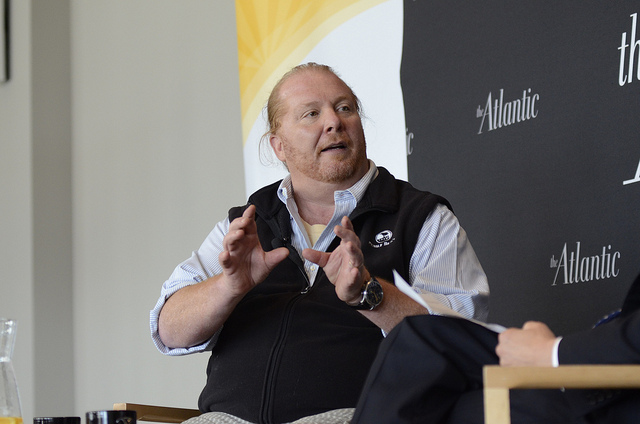

On Monday, Eater published an investigation into alleged sexual harassment by Mario Batali—chef, writer, and since 2011, co-host of ABC’s daytime show The Chew. Four women described to Eater reporters a pattern of behavior spanning over two decades that included inappropriate touching. Three of the women were Batali’s former employees.

According to the report, the first formal complaint against Batali was filed two months ago at his company, Batali & Bastianich Hospitality Group, which manages two dozen restaurants. In a statement to Eater, Batali said he was stepping away from the company, which has reported over $250 million in annual revenue. He did not deny the allegations. ABC has asked him to step away from The Chew, even though the network said it is “unaware of any type of inappropriate behavior” involving Batali and anyone affiliated with the show.

Batali’s former employees allege misconduct at Pó, an Italian restaurant he co-founded in New York City’s West Village, in the 1990s. The women claim Batali repeatedly grabbed and groped them, sometimes “in a cramped passageway between the dining room and the kitchen,” where he would “smell” an employee. They also describe humiliating, demeaning behavior. One woman claimed Batali had forced her to straddle him in plain view of other employees.

Batali’s alleged victims told Eater that his lasciviousness was the price they paid for advancing their careers

Batali is perhaps America’s most familiar Italian chef, second only to Boyardee. He’s a celebrity and icon of the dolce vita approach to life. His face adorns pasta sauces and kitchen products, many of which he stocks at Eataly, a chain of Italian marketplaces in which he’s a minority shareholder. Before he walked his bright orange Crocs onto The Chew, he hosted Molto Mario, one of the Food Network’s first hit TV shows. He’s a natural on camera, the bearer of a jolly conviviality, and the chef behind the Obama administration’s final state dinner, which The New Food Economy chronicled here.

Power, it’s said, is a drug. And Batali’s alleged victims told Eater that his lasciviousness was the price they paid for advancing their careers. “I feel very complicated feelings toward him,” one said. “In some ways, he was very supportive and he used his power and influence to connect me.” Others claim he used his position to harass, coerce, and denigrate women while they were at work. GQ notes that Batali, in his apology, equated his behavior with gastronomical excess. “We built these restaurants so that our guests could have fun and indulge,” he said, “but I took that too far in my own behavior.”

And more trouble befell Batali on Tuesday, when restaurateur Ken Friedman was forced to take leave from management of his restaurants, including the Spotted Pig, in which Batali is an investor. Ten female employees, who include front-of-house staff at two of Friedman’s restaurants, alleged sexual harassment to The New York Times. They claimed Friedman groped them in public, texted them for nudes, and forced them to work all-night shifts for private parties that included public sex and catcalls. Guests at those parties included Batali, said the Times, which also reported that he groped and kissed an unconscious woman on the third floor of the Spotted Pig, a closed-door environment that employees nicknamed “the rape room.”

Friedman’s accusers say that his “unusually sexualized and coercive” work environments transcend the usual looseness of restaurant culture. “There is a grab-ass, superfun late-night culture,” said Carla Rza Betts, who left the company in 2013 after multiple episodes of harassment from Friedman. “I love that part of the industry. But there is a difference between fun and sexualized camaraderie and predation. When you are made to feel unsafe or dirty or embarrassed, that is a different thing.”

Batali and Friedman are the latest restaurateurs to be accused of misconduct after alleged victims have brought their workplace stories to the press

Friedman and his business partner, the chef April Bloomfield, made their names with The Spotted Pig, the Michelin-starred gastropub they co-founded in 2004. They operate four other New York City restaurants, as well as restaurants in San Francisco and, as of Friday, in Los Angeles. In 2016, the James Beard Foundation named Friedman its outstanding restaurateur of the year. Bloomfield denied any participation in Friedman’s harassment, noting that he took care of the dining room and bar, while the kitchen was her province.

Last year, Friedman spoke with The New Food Economy about his experience opening restaurants in prominent hotels, including the Breslin in Chelsea’s Ace Hotel, where sexual harassment, including ass-slapping and uncomfortably long hugs, is alleged to have taken place.

Batali and Friedman are the latest restaurateurs to be accused of misconduct after alleged victims have brought their workplace stories to the press. In October, celebrity chef and restaurateur John Besh stepped down from his restaurant group after the New Orleans Times-Picayune reported that 25 women had claimed they were sexually harassed by male co-workers and managers, including Besh himself. Others, including celebrity chef and television host Anthony Bourdain, have intimated that this is only the tip of the iceberg. Bourdain tweeted on Monday: “I’ve been sitting on stories that were not mine to tell.”

What’s now coming into focus is just how systemic sexual misconduct is in the chummy, close-knit restaurant industry, where labor laws are sometimes flouted and employees are made to feel they are part of a “family.”

Last month, the Washington Post interviewed 60 female restaurant workers in an attempt to understand why the industry is particularly hostile for women. As part of its reporting, the Post said that the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission received the most complaints of sexual harassment from women working in the hotel and food industries. Additionally, the Restaurant Opportunities Center United (ROC United), which advocates for higher wages, found that two-thirds of female restaurant workers are sexually harassed by management. The Post hypothesized that restaurant kitchens “are a man’s world,” owing to a system that emerged in the French military. Home cooking, on the other hand, has long been seen as women’s domain.