rusvideo/iStock

Chances are, you eat bananas. Since they’re the country’s most popular fruit, purchased by nearly 70 percent of people in the U.S., you’re likely to have a bunch ripening on your countertop right this minute, somewhere between waxy yellow and speckled brown. The appeal is clear: Bananas are tasty, filling, potassium-packed. They’re portable, coming zipped in a handy peel. Oh, and they’re cheap—almost impossibly cheap.

Strangely, we pay less for bananas than we do for durable, easy-to-transport items of produce that come from much closer to home. Considering that the delicate and intensely perishable fruit lives no more than two weeks once chopped from the tree, and is shipped from thousands of miles away in chilled containers, it’s unthinkable that it costs less than white potatoes, or carrots—which both go for about 70 cents a pound at retail, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BOL). Even dry yellow onions, which can last for two to three months in the pantry, cost Americans nearly a buck a pound in 2018. And yet the humble banana averages only 57 cents per pound, according to BOL data, making it by far the cheapest item in the produce department.

That affordability is a key part of the banana’s allure, but it’s also something of a quiet mystery. How is it possible that a temperamental, tropical fruit can be such a bargain?

Part of the answer lies with retailers, who—for reasons I’ll explain—routinely sell bananas at a fractional markup, or even occasionally at a loss. But that low cost comes at a price. According to a 2018 report from Fairtrade International, a nonprofit organization and certifier advocating for agricultural producers in developing countries, modern banana production causes a host of social and environmental problems, from chronic underpayment of workers and workplace harassment to habitat loss and water pollution. The costs we don’t pay at the register—about $6.70 per 40-pound wholesale box, according to the report—are externalized onto smallholder farmers and the employees of banana plantations, as well as onto the land itself.

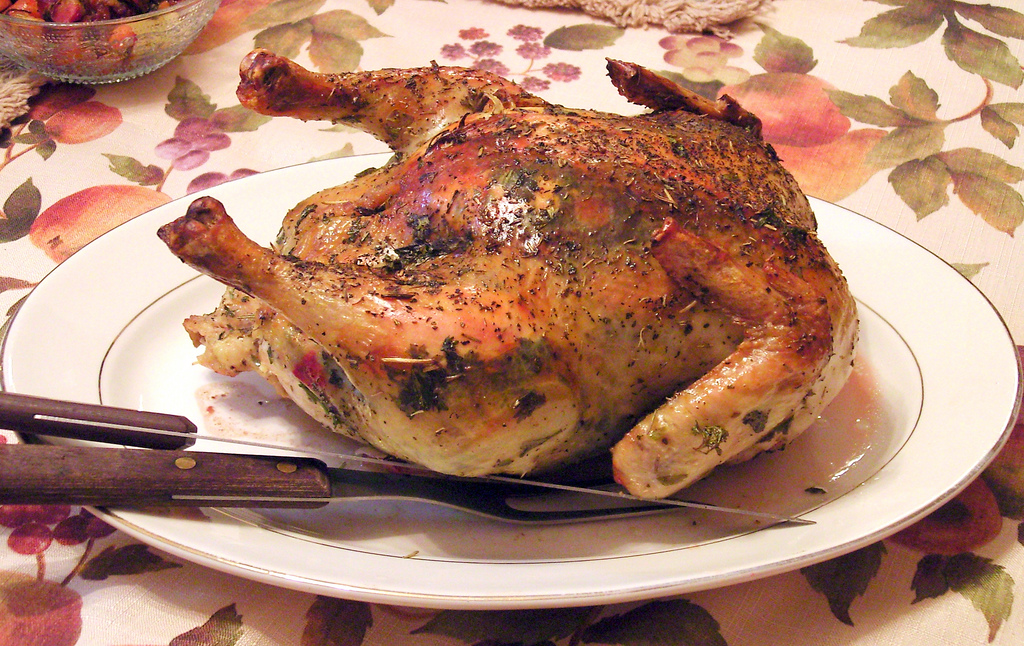

Joe Fassler

Joe Fassler A shopper inspects bananas at a Whole Foods Market in Brooklyn, New York—where they cost only 49 cents per pound—by far cheaper than anything else in the produce department.

But that model, sources say, is getting more difficult when it comes to America’s favorite fruit. As competition stiffens in the grocery industry, retailers increasingly use artificially low banana prices to gain an edge. That means mission-driven companies that charge more for bananas feel pressure to reduce their prices, too—and raising prices further is out of the question. Retailers simply can’t raise banana prices to more than $1 a pound without losing customers, even if that price is fairer to workers and better for the planet. They’re held in check by a powerful constituency with enormous political clout and unreasonable demands: Us.

? ? ?

The cost of most things—from oil to your Netflix subscription—will change unexpectedly from time to time. But the sticker price of bananas seems to remain remarkably steady, almost if by magic.

In 2018, the wholesale cost of bananas rose significantly due to a number of factors, including striking workers in Honduras and flooding in Costa Rica. According to World Bank data first reported by The Wall Street Journal, retailers paid wholesalers $0.577 a pound in the first two months of 2018, an all-time high. And yet, the average retail price paid for bananas in the U.S., according to BOL data, was $0.571 a pound during the same time period. The nation’s grocery stores were selling bananas for less than they were worth.

That price rigidity is due, in part, to the contracts most grocery stores sign with banana wholesalers. According to Jeff Cady, director of produce and floral for the regional grocery chain Tops Markets, these contracts lock in price and volume for long periods of time, typically between one and two years. Grocers tend to like the stability that comes with longer-term contracts, Cady says, though it does mean that, when market forces cause prices to rise, they can get stuck with the bill.

But contracts don’t fully explain why the price of bananas is lower today than it was a decade ago. That continual downward pressure results from our own unusual attachment to the fruit. It’s a relationship that goes back more than 150 years.

All that changed in the late 1800s. In a few short years, a handful of entrepreneurs built an implausible supply chain that put bananas within reach for most Americans. “They did it by developing a formula the banana conglomerates still employ today: Work on a large scale, control transportation and distribution, and aggressively dominate land and labor,” writes Dan Koeppel, in his book Banana: The Fate of the Fruit that Changed the World. “The result? The banana cost half as much as apples, and Americans couldn’t get enough of the new fruit.”

In addition to chronicling their ruthless approach to worker exploitation, Koeppel’s book goes into great detail about the lengths fruit companies went to overcome the banana’s price and perishability factors, including selling vast amounts of the fruit all picked on the same day, so they ripen at the same time, and shipping them across the ocean on climate-controlled containers. That basic technology is still in use today, though it’s been made even more sophisticated with special temperature-controlled ripening facilities that use a mixture of humidity control and ethylene gas to make sure each shipment is ready for its produce department closeup.

bgwalker/iStock

bgwalker/iStock Banana shipments in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

The robust transportation infrastructure has accomplished huge economies of scale, and that has helped to keep costs low for retailers. But grocers themselves also need to keep bananas cheap for shoppers. Because they spoil so quickly, bananas have always been priced to sell. What doesn’t sell quickly rots. That’s the worst-case scenario, since food that goes bad on the shelf is wasted money. As such, bananas have always been a volume game: buy them in huge quantities, sell them cheaply before they spoil, hope to make a little bit per bunch.

“Grocery stores believe that they have to charge a lower price because if they don’t sell the bananas on the shelf, that’s a total loss,” says Nicole Vitello, president of produce at Equal Exchange. “They can’t sell them the next day, they can’t keep them for a month until they sell enough. They’re gambling each time they put those bananas out.”

It didn’t take long for Americans to become attached to the notion of bananas as cheap staple, something you could chuck into the shopping cart almost without thinking. In fact, Koeppel writes, outrage ensued when the U.S. government proposed taxing bananas at a nickel per bunch in 1913. “Don’t make the poor man’s fruit and food any dearer,” The Wilkes-Barre Dispatch wrote, in an editorial that year. The New York Times argued that, even if one accepted the idea that bananas were not a staple food, it was wrong to make life’s small pleasures harder to afford for the masses. “They are entitled to their little luxuries exactly because they are poor and their luxuries are few,” the paper wrote. “[The banana] is not the less a food because it is so toothsome and sweet.” When the Underwood-Simmons Tariff Act was passed later that year, which substantially reduced the average tariff on imports, the banana provision was not included.

This painting of a banana by James Marion Shull (1872 – 1948), commissioned by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, dates to the era when Americans were first becoming enchanted with cheap bananas

“As the grocery corridor gets more difficult, stores are desperate to keep shoppers in the store,” Vitello says. “Stores typically go for a 30- to 40-percent margin in the produce department, because they have to deal with shrink [spoilage] and overhead and all these other things. But for bananas, typically you see them more at a 10- or a 15-percent margin for stores. And, with many stores now, they’re literally practically selling them at cost.”

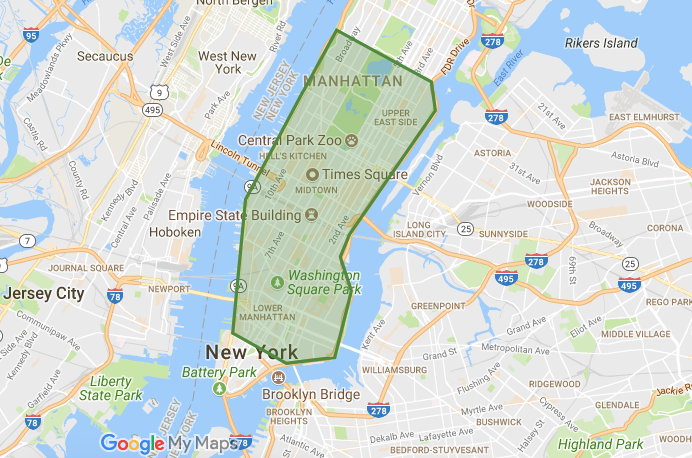

In the rare instance that retailers do sell bananas at eye-popping discounts, it can reverberate throughout the industry. When Amazon officially took control of Whole Foods in late August of 2017, it mounted a shock-and-awe discounting campaign, lowering the price of important household staples dramatically. One of the biggest discounts was to its Whole Trade bananas, which were lowered 38 percent to just 49 cents a pound. That move did more than get customers excited about making a trip to Whole Foods. A look at BOL data suggests that this had an industry-wide affect, lowering the average retail price by almost two cents in September of 2017, the largest month-to-month price drop in several years. The point is that, when one retailer lowers its prices on bananas, others feel pressure to do it as well.

In this context, brands like Equal Exchange have struggled to make the case to shoppers that it’s worth it to pay a little more for bananas. When it comes to goods like coffee, which we’re more likely to think of a higher-end product with a whiff of indulgence, that model has had significant success, leading to demonstrable social and environmental benefits. But the same logic doesn’t apply when it comes to bananas. It doesn’t matter if we let them rot on the countertop half the time. We’re so accustomed to their low cost that it’s come to feel like something we are owed.

? ? ?

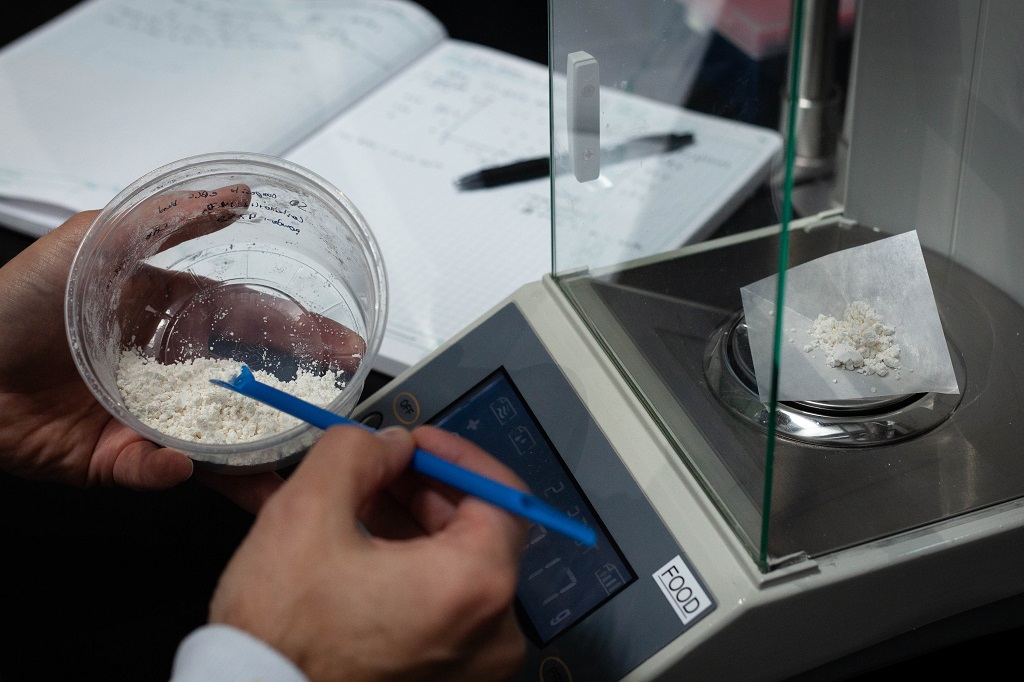

The Fairtrade International report published last year sought to determine the true cost of bananas—that is, what the fruit would cost if not artificially subsidized by damaging environmental practices and worker exploitation. The study conducted dozens of interviews with plantation managers, workers, and small producers across four key banana-producing countries: Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, and Peru.

Unsurprisingly, the study found that the true cost of banana production is not reflected in the price we pay at the grocery store. Externalized social costs were primarily related to poor wages and low job security, but the researchers also found that range of other issues related to banana production—including child labor, harassment, and occupational injuries. The study also used data from Ecoinvent and World Food LCA databases, among other sources, to determine the environmental costs of production, costs that could be offset and avoided if more money flowed back to farms. Those costs included loss of biodiversity, water pollution, and contribution to climate change. These can be offset using a range of practices, from soil tilling at the end of each cultivation cycle and reducing aerially-sprayed pesticides, to building in infrastructure for proper drainage. But all those approaches cost money.

The report concluded that we are underpaying for the price of bananas by about $6.70 per wholesale box. At a little less than 40 pounds per box, that works out to about 17 percent per pound of bananas. Fairtrade bananas, which put more money in the pockets of workers and smallholder farmers, were still found to have externalized costs of about $3.70 per box, which were mostly related to environmental damage. Both figures, though, show the toll of our addiction to cheap bananas. If retailers diverted even a 20-cent premium per pound back to producers, it could go a long way toward solving these problems.

“[The banana] is the second most noxious crop after cotton, and it continues to be a more and more toxic mix of insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, other things that are used in banana production to keep it sanitized,” Vitello says. “The human cost of workers in a situation like that with very little power to organize or represent themselves, all of those are absolutely hand in hand with the low price. Unbelievably, it wouldn’t even take that much of a price increase to have a hugely beneficial effect on people and production and environmental cost and just all of those things that are driven by the banana infrastructure and the retail price.”

But that’s easier said than done.

Jon Roessor, general manager for the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania-based grocery cooperative Weavers Way Co-op, says that he simply can’t charge more than a dollar per pound for bananas—no matter how much more beneficially they were grown, and no matter how much his shoppers say they care.

“Ninety-nine cents has always been sort of the magical feeling,” he says. “We used to see a lot of stores that were able to charge 99 cents for organic fair trade, but now you’re starting to see that is very, very difficult to maintain and you see people dropping to 89 or 79 cents or lower even. They’re paying a decent price for those bananas, and they’re literally taking it out of their pocket.”

Vitello has seen a similar phenomenon at the stores that stock Equal Exchange bananas.

“For years, we’ve been out at the store level just talking to produce managers, and I see the pressure that they are under,” she says. “They’re doing everything in their produce department to make it so that that price of bananas is like 89 cents, and then the general manager or the store manager will come and say we need to lower that to 79 cents. They’re like, ‘But we still want to carry Organic Fair Trade and Equal Exchange.’ How can that actually work? And the response is, ‘But it’s our value item.’”

“Why?” she says. “Why does it have to be the value item?”

One reason, Roesser says, is that a store that doesn’t play the price game with bananas can quickly lose customers, even when you’re talking about the kind of comparatively conscientious shopper base that might belong to a food co-op. When Sprouts Market opened its first Philadelphia store in September 2018, Roesser says its bananas were sold for 49 cents a pound, with organic bananas at 59 cents a pound.

“I just kind of shook my head,” he says. “We’re at 99 cents a pound and in my marketplace, that puts us above everybody else. Nobody charges more than we do. So we’re basically either going to have to lower the cost, and we’re going to have to come down to 79 cents, or we’re going to have to do a hell of a lot better job of telling our story.”

Certified Fairtrade bananas may have lower social and environmental costs—but they are a hard sell for supermarkets in an age of increased competition.

After all, Roesser says, bananas are usually positioned by the entrance of grocery stores for a reason. Perhaps more than any other item, bananas send a message about a store’s attitude toward freshness and price point. For Weavers Way, those expensive Equal Exchange bananas make a powerful statement about values. But they’re also something of a liability.

“You walk 10 feet in, and the first thing that you see are bananas and they’re 99 cents a pound,” Roesser says. “And it validates what you’re subconsciously already thinking about the store—that it’s an expensive place to shop.”

Price is such a powerful indicator because it’s all shoppers really see, beyond the color. Other critical factors in banana production—those that have to do with labor issues, worker compensation, and environmental stewardship—are more or less invisible to the customer. For most of us, a banana is just a banana. That’s something Roesser wishes could change.

“I almost wish that organic, fair-trade bananas were a different color because it might as well be a totally different product,” he says. “But, you know, they look and smell just like conventional bananas. It’s hard for people to distinguish unless you really get the back story.”

Vitello believes there is an opportunity to educate the public about the benefits of paying more. According to a Fairtrade survey, 64 percent of American consumers said they would spend 10 cents more per pound on fair-trade bananas. That’s not a lot of money, when you consider how much tangible good it might do if it funnels directly back to workers and smallholder farmers.

“Even people that are struggling economically, if you could show them that there is a direct benefit to paying 10 or 20 cents more for their bunch of bananas, I think they would do it,” Vitello says. “I don’t think that’s the thing that’s breaking them. Right? Yet, no one’s asking anyone to do that, and connect on a human level with this product.”

Low cost tends to lend products an air of invisibility. It’s only when a purchase really costs us that we start to look more closely, asking larger questions. And the singularly low cost of bananas has thrust them into a unique position in our lives. They’re both ubiquitous and completely unexamined. We rely on them completely, and yet we know nothing about them. That distance has been exacerbated by the banana industry, which happily supplied a mythical alternative supply chain in the earlier days—Miss Chiquita and her dancing bananas—and has continued, through aggressive pricing, making it all too easy for us to lower a heavy bunch into our shopping cart without thinking.

“It’s just sort of a yellow plastic fruit that’s on the shelves 52 weeks of the year, and no one ever talks about where it’s grown, or that people are involved in it,” Vitello says. “You just sort of think it appears magically on your shelves every single day, the same color. It’s all designed for you to not think about it. But if you did think about it really at all, you would find some pretty nasty information that would cause you to have to question everything about it. There is not a great story to tell.”