Jonas Bonnedahl

Scientists are mapping the migratory patterns of ducks in an effort to stave off another avian flu outbreak.

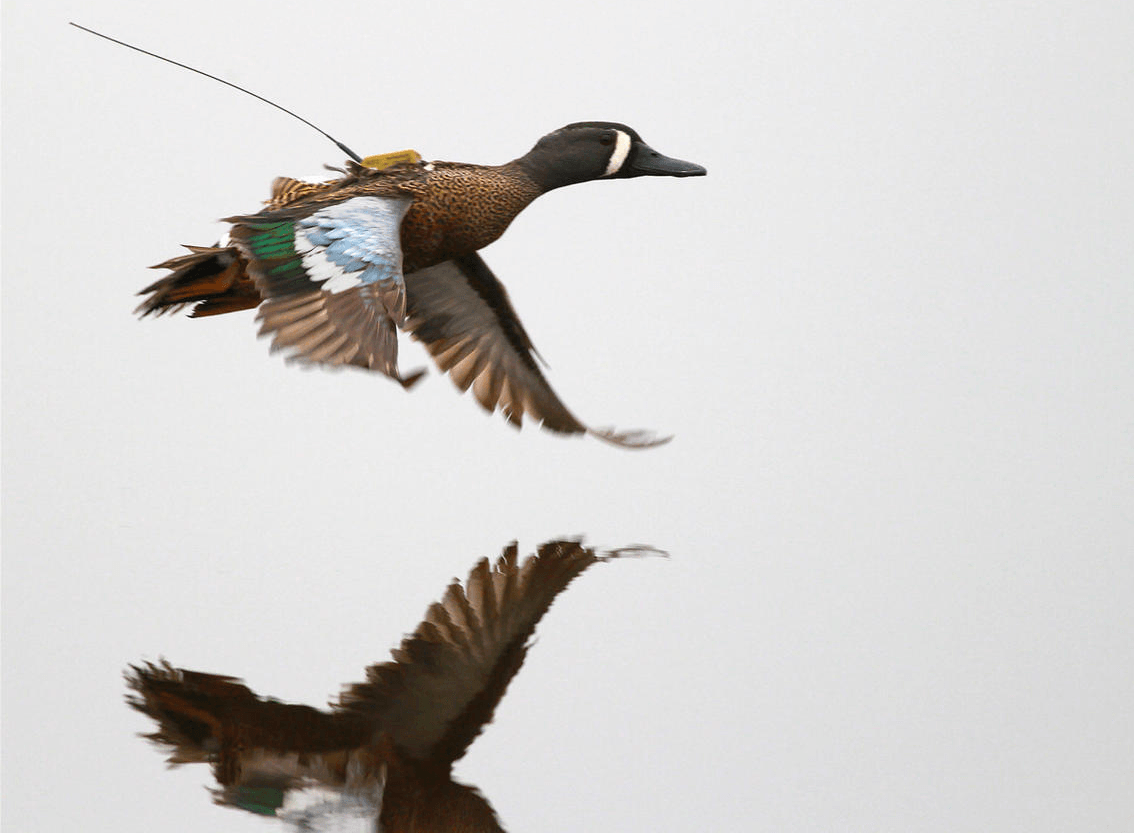

Ecologists are equipping a team of ducks with satellite transmitters to help prevent the next outbreak of avian influenza.

While veterinarians and poultry experts have long suspected that wild waterfowl are unwitting disease vectors for chicken and turkeys, little is known about exactly where the biggest avian flu transmission risks are located along the food chain. In a recent study published in the Journal of Applied Ecology, researchers used location-tracked birds to map their flight patterns relative to poultry farms, in an effort to bring the areas most vulnerable to outbreaks into greater clarity.

Avian flu poses a constant and costly threat to the domestic poultry industry: Highly pathogenic strains cause fatal disease in chickens and turkeys, which can then spread like wildfire through entire flocks. Viruses on one farm can be transmitted to neighbors, and even low pathogenic avian flus (which cause mild or no symptoms) still present a looming danger, as they can (and do) mutate into highly pathogenic variants. Avian flu outbreaks have repeatedly upended U.S. chicken and turkey supply chains in recent years.

Take, for example, the 2014-2015 outbreak which spread to more than 20 states over six months, and forced producers to cull more than 50 million chickens and turkeys. Deemed the “largest poultry health disaster in U.S. history” by the Department of Agriculture (USDA), the outbreak led to the destruction of one in every eight egg-laying chickens and one of every 12 turkeys in the country. According to one economic analysis, the fallout led to $3.3 billion in food system-wide losses.

To conduct the study, researchers captured 42 blue-winged teal ducks, a species common throughout North America, and attached solar-powered satellite transmitters to them using harnesses secured over their sternums to track their movements over time.

Just a year later, another avian flu outbreak forced producers to cull more than 400,000 turkeys in Indiana. In 2017, the disease took out 129,000 chickens across two Tennessee farms. Last April, it led to the culling of 361,000 birds across 13 farms between North and South Carolina.

The top culprit in each of these crises? Wild waterfowl. Turns out, ducks and geese are natural carriers of avian flu-causing viruses, and can sicken their chicken and turkey cousins. Oftentimes, waterfowl are asymptomatic when infected, leading some researchers to dub them “silent spreaders.” Waterfowl can shed the virus through feces onto soil, water, or farm equipment, which can then transmit pathogens to chickens and turkeys.

“Wild waterfowl are one of the natural reservoirs for these avian influenza viruses,” said Diann Prosser, a wildlife ecologist for the U.S. Geological Survey and co-author of the paper. “To understand what they’re doing and where they are, we need to know the connections between the wild [waterfowl] and where the disease might be able to be transmitted, for example agricultural industries.”

To conduct the study, researchers captured 42 blue-winged teal ducks, a species common throughout North America, and attached solar-powered satellite transmitters to them using harnesses secured over their sternums to track their movements over time. Researchers chose the species because of its prevalence and evidence that it can host many avian flu-causing viruses. After data about the birds’ movements started rolling in, Prosser and her colleagues categorized them into three different patterns: long-distance flights, short-distance flights, and periods spent on the ground. It’s that last category that Prosser and her team were most interested in, hypothesizing that birds on the ground posed the greatest risk to poultry facilities.

The data helped Prosser’s team drill down the precise regions and times when wild waterfowl were most likely to spend time in close proximity with poultry facilities.

While grounded, “they’re feeding in wetlands and wet areas, they’re picking up potential virus particles that are in the water and sediment, and then they’re eventually defecating,” Prosser said. “So if they’ve got [avian flu], they could be shedding virus in the environment.”

Researchers then compared the ducks’ movements against a USDA map of poultry farms across the country, including both commercial facilities and backyard farmers, and chicken and turkey producers. Put together, all this data helped Prosser and her team drill down the precise regions and times in which wild waterfowl were most likely to spend time in close proximity with poultry facilities.

Here’s what they found: Commercial chicken facilities in the South (defined as regions south of the 40th parallel) appeared to face the highest risk of pathogen spillover during spring migration in April and May. In contrast, commercial chicken and turkey facilities further north seemed to face the greatest overlap with waterfowl during fall migration, between mid-September and mid-November.

“Our results suggest that [avian flu] spillover risk from [blue-winged teal ducks] to commercial chicken facilities may be elevated during the spring and autumn migrations when wild birds stopover near poultry operations while in route to breeding or overwintering habitats,” the authors wrote.

“Every flyway is basically a disease highway.”

This lends further evidence to a phenomenon that researchers have long suspected—that avian flu risks are highest when wild birds are in migratory mode. In the case of the 2014-2015 outbreak, experts noted, cases appeared to cluster together along the intersection of the Central and Mississippi flyways, two common flight routes for migratory birds.

“Every flyway is basically a disease highway,” said George Thomas Tabler, an extension professor specializing in poultry at Mississippi State University. Tabler offers guidance to chicken farmers on disease prevention, and stresses that sanitizing equipment and even shoes before entering farms can help minimize the risk of transferring the virus from one place to another. “Where avian influenza is concerned, nobody can be too careful.”

As for Prosser’s research, she stresses that there remains a lot more to learn about the relationship between waterfowl and poultry farms. After all, this recent study looked at just one species of waterfowl. There’s a sky full of other ducks and geese still unstudied and free from pesky location-tracking devices. Maybe some of them are taking off right now, headed south for the winter. Chances are, they have different migratory patterns and susceptibilities to avian flu-causing viruses from one another.

“It’s a much more complex picture,” Prosser said. “This is kind of the first step in a work process.”