Danielle Pycior/Missourian

Farms across the Midwest are struggling to hire domestic employees. In Illinois, the number of foreign agricultural workers has increased more than 250 percent in the past five years.

Linnea Kooistra’s roots in farming go back 10 generations. She and her husband, Joel, were both raised on dairy farms, and they operated their own in Woodstock, Illinois, for over 40 years. But in 2018, they were confronted with the hard decision of selling their herd of almost 300 cows.

This article is republished from The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. Read the original article here.

After months of deliberation, they decided to sell the herd in part because they relied on immigrant workers to care for and milk the cows, and they feared losing their workforce.

“The labor situation, you know, it was just so hostile,” Kooistra said. “We were just worried that we’d lose our labor pool. We couldn’t do it, the two of us. There was just so much work. We just couldn’t do it.”

Farming generates $19 billion annually in Illinois, according to the state Department of Agriculture, and the state is among the top producers of commodities such as corn, soybean and pork. But farmers say they struggle to find local workers. As the farming industry faces a severe labor shortage, producers rely overwhelmingly on foreign-born workers to maintain crops and tend livestock.

Kooistra had three full-time employees and two part-time workers on the farm. She and her husband found it was becoming increasingly difficult to find employees willing to be at the farm at 4 a.m. to tend the cows, so around the year 2000, they switched to an immigrant workforce.

“People have different reasons why they would not like to work on a farm,” Kooistra said. “From my experience, at a certain point, there were just no longer people interested in working on farms, so once we switched to an immigrant workforce, we were able to attract employees and quality employees.”

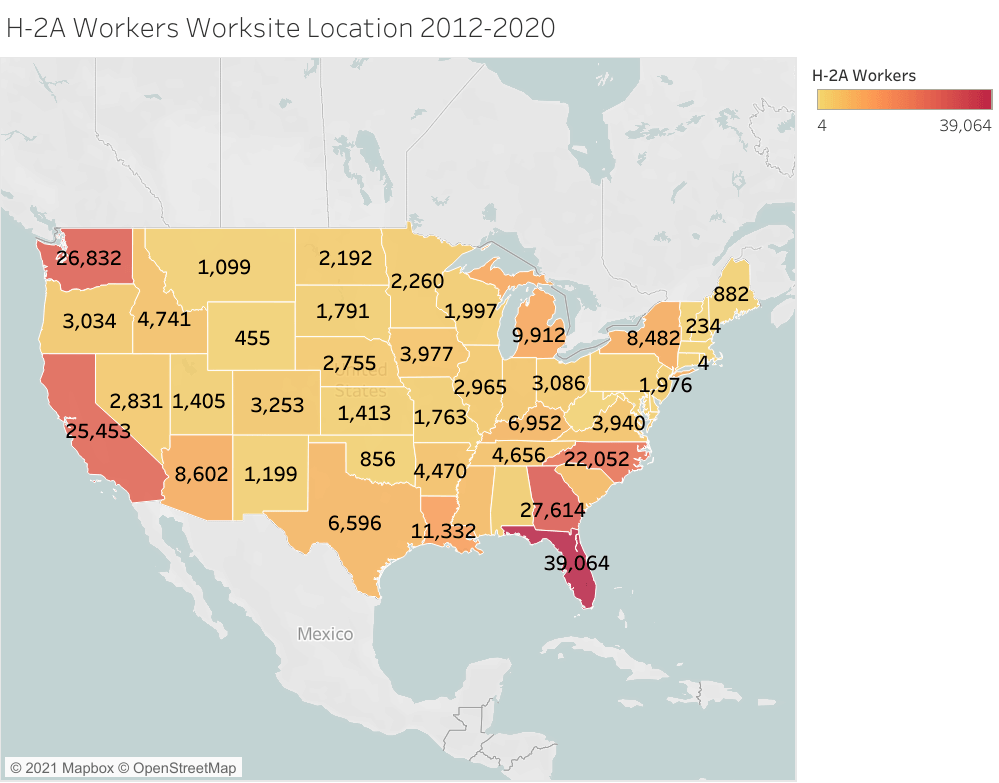

Nationwide, between 2010 and 2019, the number of certified H-2A positions in the U.S. rose by more than 220%, according to a USDA data analysis.

The labor pool for those who want to work on a farm is small and isn’t expected to get any bigger. Employment of agricultural workers is projected to only grow 1% from 2019 to 2029, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics — slower than all other industries.

In 2020, there were 6,260 workers in farming, fishing and forestry occupations in Illinois, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Nationwide, according to the latest Farm Labor Survey, there were 613,000 workers hired directly by farm operators last April, an 11% decrease compared to April 2020.

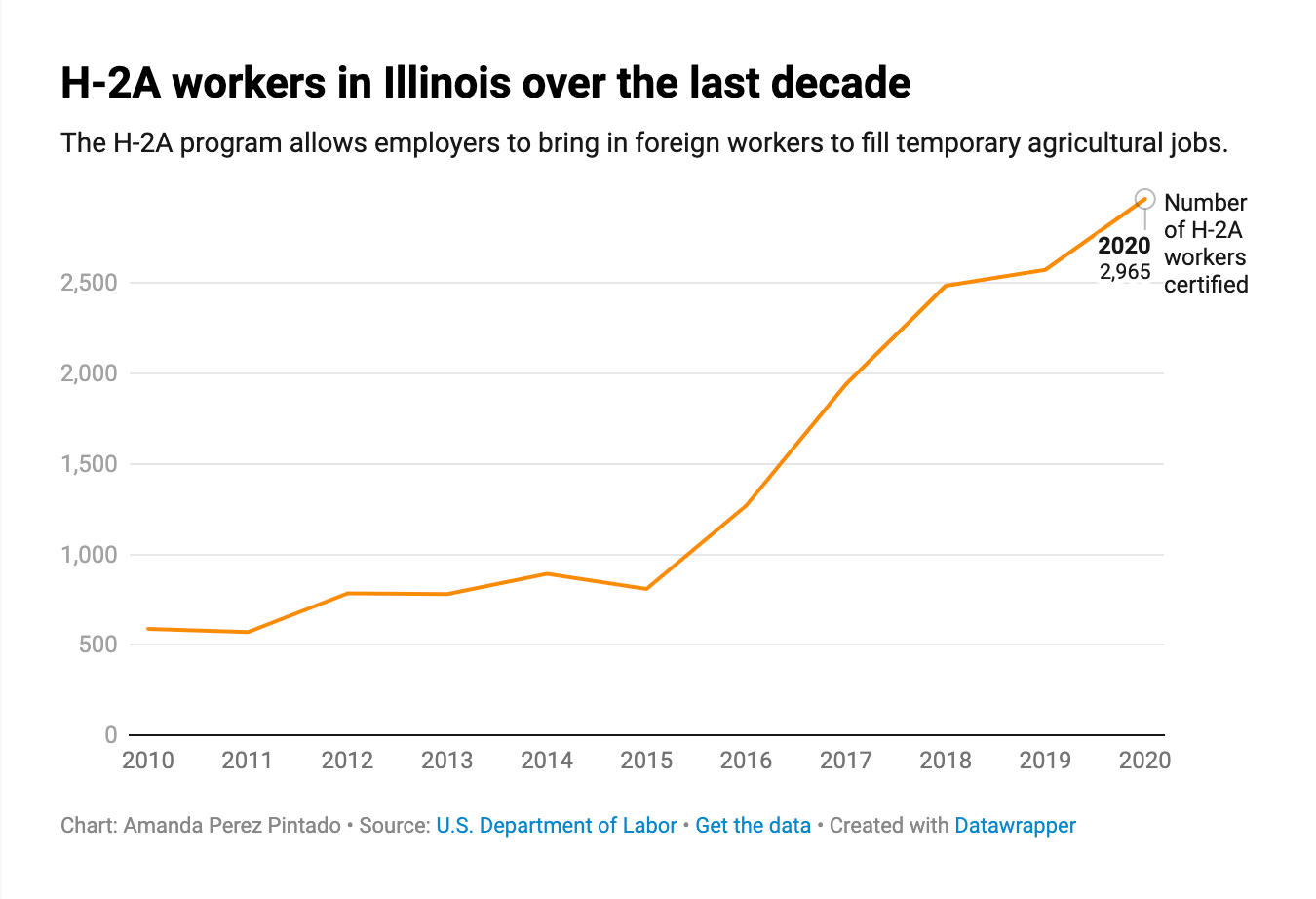

Meanwhile, the reliance on the H-2A temporary agricultural program has steadily increased over the years. The number of workers with H-2A visas in Illinois worksites went up by 266.5% in five years, from 809 in 2015 to 2,965 in 2020.

Nationwide, between 2010 and 2019, the number of certified H-2A positions in the U.S. rose by more than 220%, according to a USDA data analysis. All areas of agriculture saw an increase, but the growth in H-2A employment was more pronounced in product categories with high labor requirements and seasonal jobs, including fruit and tree nuts, vegetables and melons.

Adam Nielsen, Illinois Farm Bureau’s director of national legislation and policy development, said teenagers used to do seasonal labor in the past, but they have moved on to other jobs. Agricultural labor, he said, is not particularly attractive for local workers because it’s intense.

“If you’re not able to find people,” Nielsen said, “either you do it yourself or you exit that part of the industry.”

H-2A workers in Illinois over the last decade

View the complete chart here.

Hog farmers feel the burden

Central Illinois pork producer Phil Borgic, owner of Borgic Farms, Inc., started farming after he graduated from college in 1978. He first started noticing a decrease in farm workers about 20 years ago. The labor pool, he said, has been getting smaller since then. Borgic said the biggest hurdle in attracting workers is that people “don’t know what we do everyday.”

“It’s not working in slop and mud all day,” said Borgic, adding that the facilities are ventilated and clean. “That’s been a conscious effort on my part — upgrade our facilities, plenty of light, make things clean and appealing to our workers, besides being friendly to our pigs.”

Mike Haag is a fourth-generation hog farmer in Emington, Illinois. He raises 17,000 hogs a year on his family farm. The number of hogs at the farm has decreased in recent years in part because of labor shortage. At the moment, he has two full-time employees. Six years ago, when the farm had sows, he employed 12 people.

“This last winter, I spent two and a half months by myself out here trying to do it all myself,” Haag said. “We’re looking at reducing our numbers again, just because I’m to the point where I don’t want to have to do it all.”

For individual farmers, he said, it’s difficult to compete with larger employers that are able to offer their workers benefits.

“A lot of bigger corporations can put together benefit packages way cheaper than what small individual farmers can,” Haag said. “I mean, just to, to present like a health insurance package for a family that’s working for you is at a cost. Well, we priced some last year to try to come up with a health insurance plan, and it was going to cost us between $17,000 and $20,000 a year to come up with a health insurance program.”

For a few years, he hired foreign workers through the H-2A program. The seasonal agricultural program allows employers to bring in foreign workers to fill temporary jobs. One of the requirements to qualify for the program is to prove that there are not enough U.S. workers available to do the work.

“We worked with a lot of South Africans that came up through a visa program, and for a while, that worked pretty good,” said Haag, who brought workers through the program for about 10 years. “But it became harder and harder to get the help, and it was seasonal. They could only be here for nine months.”

Haag stopped hiring foreign workers through the program about six years ago largely because of the cost.

View the complete chart here.

The program requires employers to pay for workers’ transportation and provide housing. H-2A workers must be paid a government set wage. In Illinois, this year’s rate is $15.31 an hour, an amount above the state’s $11 minimum wage.

Last year, according to the USDA, the average duration of an H-2A certification was 5.6 months. Despite the coronavirus pandemic, which limited movement across borders, the number of foreign workers employed in Illinois under H-2A visas between 2019 and 2020 went up 15.2%.

Labor advocates have long pointed out flaws in the program and have called it exploitative, particularly because of guest workers’ dependence on their employers.

For Mariyam Hussain, supervisory attorney of Legal Aid Chicago’s migrant farmworker project, an increase in workers who hold H-2A visas is cause for concern because they could be taken advantage of by employers.

“They may not have community ties, and they depend on their employers for housing, food, water, wages, all of which is generally included in the H-2A job orders in the contracts,” Hussain said. “And so if an employer is a bad employer, which happens a lot, and doesn’t provide the adequate amount of food, water, or adequate housing, there’s not a lot they could do.”

A bipartisan farm worker bill

The Farm Workforce Modernization Act aims to make changes to the guestworker H-2A program and provide a pathway to citizenship to agricultural workers. The bipartisan bill, passed by the House in March, is now stuck in the Senate, as legislators debate over immigration.

The proposed legislation would expand the H-2A program, streamlining the process and providing visas to year-round producers such as dairy and hog farmers. The bill would also freeze the minimum wage employers are required to pay guest workers.

The bill has strong backing from farm owners. Organizations representing producers such as the National Pork Producers Council are pushing for the proposed legislation to be passed, advocating for year-round access to the H-2A program without a limit on the number of visas issued.

Large groups that advocate farm workers such as United Farm Workers and Farmworker Justice support the bill, highlighting its significance in providing a pathway to citizenship for the roughly 1 million undocumented agricultural workers.

The proposed legislation would expand the H-2A program, streamlining the process and providing visas to year-round producers such as dairy and hog farmers.

Smaller grassroots organizations, however, have expressed concern and disappointment over the bill, The Counter reported. Some groups that oppose the proposed legislation say it does “nothing to address the root causes of labor exploitation that farmworkers face on a daily basis.” The Food Chain Workers Alliance argues the bill would “make conditions even more difficult” for laborers and expands the H-2A program without providing oversight.

The Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by Illinois Sen. Dick Durbin (D), on July 21 held a hearing on the bill, which included testimonies from Kooistra and Secretary of Agriculture Thomas Vilsack.

“I urge my Congressional colleagues here today to meet this moment of bipartisanship efforts and move legislation forward this year that provides legal status and a path to citizenship for farmworkers – securing a reliable workforce for our agriculture industry – as well as legislation that provides a living wage for these essential workers along with strong labor protections,” Vilsack said at the hearing, marking the first testimony from a secretary of agriculture before the committee in two decades.

Kooistra made a similar plea to the senators. She said current workers who are undocumented deserve to work toward citizenship and advocated for the expansion of the H-2A program to give dairy farmers access to guest workers year-round.

“Do we want our food produced in this country where we have the safest food supply in the world?” Kooistra asked the committee. “The ag labor crisis on our farms is an issue of national security that must be addressed, and it must be addressed now.”