Boston Public Library Tichnor Brothers collection

By now, many realize that the continued existence of the neighborhood supermarket is not a given, and that the familiar model of food retail that dominated much of the 20th century may soon be a thing of the past. In a new article co-published with Longreads, The New Food Economy’s Joe Fassler tells the story of this decline, how regional grocery chains got into the fix they’re in, and how they must change if they’re going to survive.

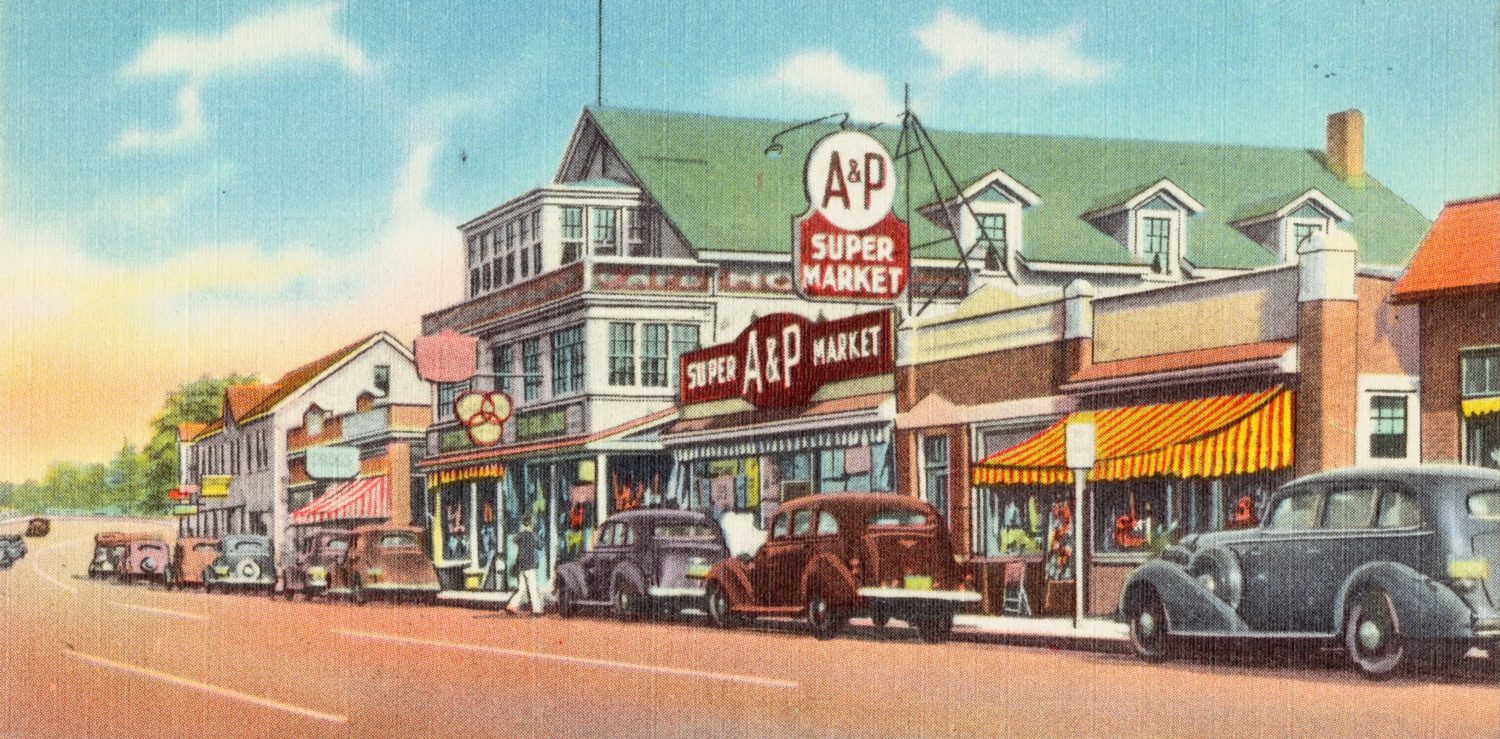

But for some historians, it’s strange to see the chain supermarket cast in the role of the underdog. In the decades before World War II, these stores were Goliath, not David. Specifically, A&P—the pioneering, once ubiquitous chain that ceased operations in 2015, after 156 years in business—was seen as the great antagonist of Main Street, a company so powerful some said it threatened American prosperity. The backlash was so severe that the U.S. congress very nearly passed a law that would have accomplished what is almost unthinkable today: an effective ban on chain stores.

That backstory, detailed in Marc Levinson’s book The Great A&P and the Struggle for Small Business in America (2012), is little known in 2019. And, ultimately, the measure with the power to redefine American commerce didn’t pass—thanks in large part to A&P’s extraordinary lobbying efforts. Through a combination of aggressive PR, political favor-mongering, market clout, and the timeless appeal of everyday low prices, A&P persevered. But the story of how the chain survived isn’t just entertaining in its own right. It also provides the model for how today’s titans of retail—from Walmart and Amazon to Google and Apple—work to preserve their own monopolies, ultimately convincing us that we’re better off without the competition.

—The editors

~

Between 1920 and 1940, a legitimate movement to limit the spread of chain stores gathered steam. At one point, 26 states had passed independent taxes on chains, a dozen radio stations were devoted to opposing them, and 40 newspapers had explicit anti-chain policies. Like soda taxes today, the movement bred strange political alliances—at one point, the KKK, black business owners, women’s groups, progressives, Southerners, and Midwesterners were all united against the perceived Wall Street takeover of rural America. The anti-chain movement’s successes were not insignificant: Congress passed two federal laws meant to limit practices that gave chain stores an advantage over independent grocers.

Conrad Poirier

Conrad Poirier The early years of A&P—the pioneering, once ubiquitous chain

The movement reached its legislative climax between 1938 and 1940. A bill that would effectively tax chain stores out of existence was introduced in the House by Representative Wright Patman, a folksy Texas cotton-farmer-turned-populist-politician who’d literally ridden a horse six miles to high school (and whose eponymous committee later played a key role in the Watergate scandal that eventually ended Richard Nixon’s presidency). Patman had built his career on crusading against monopolies, and with more than 70 co-sponsors, passing a so-called “death tax” on chain stores would’ve been his crowning achievement. By late 1939, Patman claimed he had the support of 150 representatives and it looked like the bill would pass.

Yet between 1939 and 1940, all that support dissolved into thin air. The “death tax” never even came to a vote.

The bill’s failure marked the end of the anti-chain movement. The next year, the U.S. entered World War II, which marked a turning point for the way people saw their role in the country’s economy. Writing in the Iowa Law Review in 2005, legal scholar Richard C. Schragger described the period this way: “the ideology of economic citizenship that animated chain opponents had dissipated; post-war America was characterized by the full realization of the mass-consumption economy.” By the time newlyweds were settling into the country’s freshly constructed suburbs after the war, the chain store had cemented its place in society.

So what happened at that crucial moment when support for Patman’s anti-chain legislation fell apart? The bill’s implosion can be attributed, in part, to a shift in the wind: Many of Patman’s progressive allies were pushed out of office in the elections that took place between the bill’s introduction and its ultimate demise, and the specter of war altered the Democratic leadership’s political priorities. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declined to go to bat for the chain store tax (more on that later).

But it was arguably one massive lobbying campaign that ultimately tipped the scales to kill Patman’s “death tax.” Financed by the A&P chain of grocery stores, it successfully neutered key support for the bill.

Ultimately, the Hartfords helped ensure the defeat of Patman’s “death tax” with a brilliant public relations strategy, one that worked to convince consumers they couldn’t afford to lose chain stores. But the playbook used to engineer the fall of the chain store tax can be traced back a few years before the crafty billionaires used it to outmaneuver their overzealous congressman. The Hartfords adapted their playbook from another chain store lobbying effort, one localized to California. It’s a simple concept: One by one, convince all the groups who oppose the chain stores to change their minds. More than half a century later, there’s some indication the strategy has stood the test of time. Critics say Amazon is following in A&P’s footsteps.

~

The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company started out selling tea in lower Manhattan, just steps from Wall Street—the symbol of hoarded prosperity its critics would evoke more than half a century later. It expanded rapidly by pricing its product lower than the competition. By the time tea prices began to fall in the 1880s, the chain was already well-established. A&P added sugar to its roster to keep its profits up, but co-owner George Huntington Hartford, grandfather of the childless brothers, worried that trading in commodities would tie the fate of the company to their fluctuating prices. He seized on a major controversy of the day—impurities in baking powder—and began manufacturing a store brand whose purity was essentially guaranteed by the A&P reputation. It was a huge success, and the company expanded to grocery.

The Washington Times

The Washington Times Starting with its promise of pure baking soda in the 1800s, A&P proved adept at giving customers what they wanted

The food industry at the time was ripe for disruption or, in the lingo of the day, “creative destruction.” The average American family spent a third of its income on food, triple what we pay today. Part of the expense was due to the fact the era’s grocery stores, which were mostly run by local business owners and staffed by their families, offered conveniences that seem luxurious by today’s standards. Customers called in to place their orders, which were subsequently delivered and paid for at the end of the month, or whenever the money was available. The significant losses inherent in such a system—labor for delivery, customers’ unpaid debts—were baked into the price of food.

Early A&P stores eliminated these expensive services. The chain’s shops looked much like their independently-owned neighbors, with items displayed behind a counter and a cashier who measures bulk goods. But there was one crucial difference: If you didn’t have cash on hand, you couldn’t buy anything. By cutting these costs, A&Ps were able to undercut the neighborhood grocers.

By the 1920s, A&P was everywhere. That decade, it operated 300 stores in Chicago alone. Yet even as the this breathtaking growth wowed the business community, independent grocers who felt threatened by the chain’s sudden proliferation were starting to get organized. A movement against the explosion of chain stores was gathering steam, and it soon set A&P in its sights.

~

“When he walks into a chain store he hopes that he is not seen by any of his friends or any of the local merchants,” wrote Edward G. Ernst and Emil M. Hartl for The Nation in 1930. “Yet he does buy in the foreign-owned stores, and the reason he most commonly gives is: ‘Money is hard to get and I must make it go as far as I possibly can.’” America was a year into the Great Depression, and anti-chain store sentiment had gone mainstream in a big way. In the series for The Nation, Hartl and Ernst reported that even high school debate teams were tackling the issue.

Some of Ernst and Hartl’s arguments against the chains are quaint by today’s standards: They spilled ink worrying that managers from out of town would have no investment in the local community, that men working around the clock in hopes of climbing the corporate ladder would leave “chain store widows” home alone, that employee morale would suffer when people worked for faraway corporations and had no stake in the success of the company as a whole.

The concern that chain stores might force independent retailers out of business was not unfounded. A&P had spent much of the 1920s consolidating its power. It purchased a milk company, then bought the country’s second-largest bakery, then began canning its own products. It built out an infrastructure to move all that stuff around and used its muscle to negotiate a $60,000 annual discount with the railroads. It asked suppliers for price breaks and blacklisted them when they refused to cooperate. In the latter half of the 1920s, it slashed its prices even further by extracting advertising fees and brokerage allowances from manufacturers, then slashing its own profits to further undercut the competition. By all measurements, it was winning the race to the bottom.

Yet in the 1930s, as more and more states responded to the outcry and implemented taxes on chain stores, A&P was caught in a difficult position: It had aggressively expanded its small stores, yet people had started flocking to supermarkets on the outskirts of town. A new model for buying food was starting to catch on: big, gleaming structures with vast parking lots and the promise of one-stop shopping. A&P’s earlier strategy, which relied on building tons of small stores, was particularly vulnerable to the new taxes, which were typically calculated based on the number of outlets.

So the Hartfords pivoted. In 1937 and 1938, they closed 4,000 stores and built 750 supermarkets. In doing so, they were able to accomplish two goals at once: Catching up with the competition and minimizing their own taxes. The strategy worked. The new big box stores made a lot more money per unit, and A&P’s leadership was able to avoid taking a public stand against the onslaught of new taxes.

New York Public Library

New York Public Library Through a combination of aggressive PR, political favor-mongering, market clout, and the timeless appeal of everyday low prices, A&P persevered

Starting with its promise of pure baking soda in the 1800s, A&P proved adept at giving customers what they wanted. It was particularly good at winning over groups outside the (largely male) business community, people who didn’t see its mere existence as a threat. Female customers, tasked with feeding their families on a limited budget, appreciated its low prices. And people of color, who were vulnerable to discrimination and price-gouging at locally owned grocers, appreciated A&P’s standardized pricing.

The company would later leverage political support from these groups to defeat the chain store taxes. In doing so, it seemed to learn an important lesson: If you can sell goods cheaply enough, you can become politically unassailable—even if your approach to doing business makes society less prosperous overall.

~

Wright Patman, the populist Texas congressman who would ultimately advance the “death tax” bill, began his federal assault on chain stores by focusing on their prices. At first, he wanted to limit the ability of muscular buyers like A&P to force wholesalers and manufacturers into giving them discounts. Doing so would be a win for wholesalers, who could preserve their sticker prices, and small businesses, who could hypothetically purchase food at the same rate as the chains and then offer competitive prices. In 1936, Congress overwhelmingly approved the Robinson-Patman Act, which made it illegal for manufacturers to give big chains preferential prices (or, if they did, they had to justify those prices under a “reasonableness” standard based on volume). It also banned buyers like A&P from asking manufacturers for side payments, like marketing fees, that were essentially discounts by another name. Another federal law, the Miller-Tydings Act, was passed in an effort to prevent chains from selling certain items like milk and eggs at a loss in order to get customers in the door.

Yet even though the passage of the Robinson-Patman and Miller-Tydings Acts did little to slow the growth of chains (and arguably hurt the little guys in the process), Patman was not deterred. His next effort would be his crown jewel—a graduated tax so high it would effectively end chain stores. In response, the chains did all they could to make sure that never happened.

~

The propaganda started in California. In 1935, the Anti-Monopoly League passed a steep chain tax. Instead of responding with the grin-and-bear-it approach chain stores had relied on in other states, a coalition in California led by Safeway decided to overturn the legislation in the most public way imaginable: By organizing more than a hundred thousand voters to petition for a referendum. If successful, the referendum would overturn the tax—and prove in the court of public opinion that people wanted the chain stores to stay for good.

To steer its efforts, the newly minted California Chain Stores Association hired the advertising agency Lord & Thomas, which had made its name a decade earlier by splashing the slogan “It’s Toasted” on cartons of Lucky Strike cigarettes. (Toasting was never unique to Lucky Strike.)

Lord & Thomas started by making a few token concessions to win over chain store employees: ID badges were updated to display names instead of numbers, and the agency encouraged chains to organize company picnics.

It also sought to win over farmers, who had been critical of chains’ downward pressure on their prices. When a glut of peaches needed to move quickly, the chains were quick to play the hero. They organized a nationwide effort to promote peaches, ensuring that the farmers weren’t stuck with rotting fruit. Lord & Thomas proposed a few other key concessions to farmers, too: the reduction of farmer-paid “advertising allowances” (forced price deductions that ostensibly paid for in-store promotion, which were technically illegal anyway) and fewer forced price cuts. Their widely publicized efforts went a long way toward weakening farm group resentment toward the chain stores.

Internet Archive Book Images

Internet Archive Book Images By cutting costs, A&Ps were able to undercut the neighborhood grocers

At its core, Lord & Thomas’s strategy was simple: The agency wanted to break up the broad cross-section of groups who supported the chain-store tax. It won over farmers by handing them one huge favor and a few nebulous promises. It won over employees by treating them just a little bit better. Finally, it won over consumers by convincing them they would lose money if the system changed.

Just before the vote, the agency introduced a catchy slogan: It dubbed the chain store tax “a Tax on You.” The referendum passed.

~

Bolstered by the success in California, the Hartfords hired Carl Byoir to help them quietly defeat a chain store tax in Brooklyn. Byoir, who had introduced the Montessori method to America (and later opened a public relations firm that promoted tourism to Nazi Germany) was extraordinarily well-connected, having met President Roosevelt many times through various clients. (Roosevelt, who seems to have found Wright Patman a bit annoying, never took a concrete stand on the chain store question.)

In 1937, Byoir successfully defeated a chain store tax in Brooklyn—and, importantly for the press-averse Hartfords, he managed to do so without the newspapers realizing A&P was involved. The brothers decided to unleash him on Patman’s “death tax.”

Byoir’s efforts began quietly. First, one of the Hartford brothers offered a rare interview to a friendly Fortune reporter, resulting in a sympathetic profile. Then, Byoir’s team took the coalition-splitting strategy pioneered by Lord & Thomas several steps further: They persuaded the Hartfords to allow A&P employees to unionize.

Unionization efforts at A&P stores had been largely unsuccessful. Perhaps most notably, in 1934, striking unions stopped deliveries to A&P stores in Cleveland. In response, A&P closed all 293 of its locations and fired 2,200 workers. At the end of the day, the Hartfords won.

Next, Byoir went after the burgeoning consumer movement by financing writer Ada Taylor Sackett’s efforts to organize housewives through her newly-minted National Consumers Tax Commission. Sackett and Byoir built out an organization of 72 staffers that organized study groups all over the country to talk about women’s issues. Taxes, of course, were always on the table.

Finally, Byoir persuaded the Hartfords to take out a five-column advertisement in newspapers across the country articulating their opposition to the chain store tax. It was an unprecedented public statement from a famously private family.

Back to the bill: Remember how 75 legislators co-sponsored the chain store tax in 1938? Seven months later, the November election knocked 25 of them out of office. Once it was reintroduced in the next session, Patman’s bill faced fierce opposition from A&P and its allies when it was reintroduced. By that time, Byoir’s team had won over the American Farm Bureau Federation and the National Grange. They’d won over real-estate groups, too. They’d even transformed a group called the National Drainage, Levee, and Irrigation Association into an A&P front.

There’s another weird wrinkle here: Just two months after the “death tax” was reintroduced to Congress, on March 29, 1939, President Roosevelt’s son asked one of the Hartford brothers for a loan of $200,000 to finance the purchase of some radio stations. That loan would be worth about $3.5 million today. The president knew about the loan and approved of it, though he never disclosed it publicly. He repeatedly declined Patman’s requests for public support before and after the bill was introduced.

The younger Roosevelt never paid off his debt, and Hartford ultimately settled it for two cents on the dollar. A subsequent investigation found no evidence that the Roosevelts did anything to support chain retailing after the money changed hands, though their silence may have been a factor in killing the “death tax.”

Less than eight weeks after the loan, the hearings on the bill ground to a halt. Support had crumbled, and Patman knew his “death tax” was headed down the tubes. He filibustered a radio station in hopes of dredging up support, and later went on NBC to compare the chains to Hitler and Stalin. None of it helped. On June 18, 1939, the Ways and Means Subcommittee refused to report the bill to the full committee. It was dead.

The demise of the anti-chain movement represented a turning point in American thinking about the economy. As Schragger wrote in 2005, “it was arguably the last time that there was a serious effort to offer an account of the relationship between economic decentralization and liberty.”

Infrogmation

Infrogmation In 2015, A&P was displaced, in part, by a comparatively new breed of company that had managed to consolidate the retail industry even further

As for A&P, it survived to see another day. In September of 1946, a federal judge ruled that the Hartfords, then aged 81 and 74, had conspired to violate the Sherman Antitrust Act. They were accused of using A&P’s size and power to keep prices artificially low. The company survived until 2015, but by then its power had peaked—displaced, in part, by a comparatively new breed of company that had managed to consolidate the retail industry even further.

Fast forward to today, and anti-monopoly advocates are again questioning who should be protected under antitrust law. In 2017, lawyer Lina Khan published a paper called “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” which argued that companies should not be allowed to engage in anticompetitive practices just because they offer low prices. The New York Times called the paper “a runaway best-seller in the world of legal treatises.”

In response to Khan’s paper, two former Federal Trade Commission officials published a paper that looked back at A&P and antitrust law. They argued that A&P was an innovator, that the government’s efforts to regulate its power was misguided. The Times writes that the officials were explicit in their efforts to paint the demise of A&P as a cautionary tale: This was a good, innovative company, and it was unfairly targeted by the government. A&P accomplished something so simple it’s accepted as fact in today’s economy: It made food cheap.

In a footnote on the first page, the authors acknowledge that they approached Amazon for funding. The company generously obliged.