Jorge Castillo

Four liquor stores in Whiteclay, Nebraska shuttered this weekend following decades of protest. Their licenses were due to expire at the end of April. On Monday morning, a local Omaha television station reported that beer trucks had arrived to collect unsold merchandise.

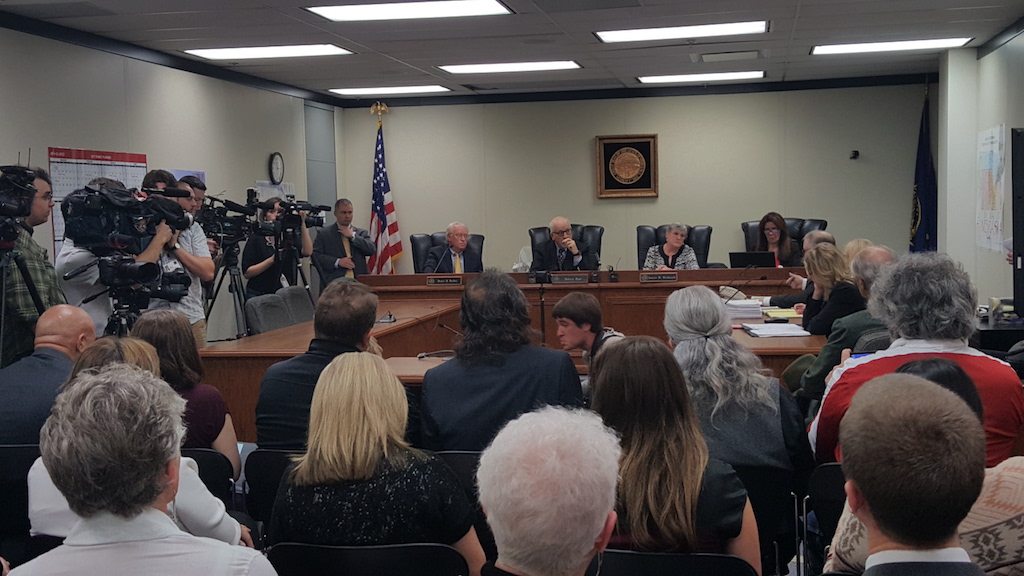

The closures, which may prove temporary, came at the end of a turbulent month of reversals of fate for the four stores. In early April, the Nebraska Liquor Control Commission held a hearing to determine whether or not Whiteclay had adequate law enforcement to keep the liquor stores open. On April 19, the commission voted unanimously to deny the renewal of the stores’ liquor licenses. Then, on April 27, a district judge overturned that decision on the grounds that the commission did not have the authority to close the stores. That same day, the Attorney General’s office appealed the district judge’s decision. The appeal means the case will be bumped up to the Nebraska Supreme Court or the Court of Appeals. In the meantime, the district judge’s ruling has been delayed until the case is heard. That means the stores had to stop selling alcohol by the end of the day on Sunday.

Indeed, the four stores didn’t open at all on Sunday. By all accounts, Whiteclay was relatively quiet with the exception of a press conference featuring speakers including former Oglala Sioux Tribe president Bryan Brewer, activists Frank LaMere and Debra White Plume, and Sonny Skyhawk, founder of American Indians in Film and Television.

An editorial cartoon by Marty Two Bulls

An editorial cartoon by Marty Two Bulls “My sister didn’t have to die because of alcohol,” Ina Rodriguez said in a video produced by the Omaha World-Herald. For her, the closure of the stores is personal. But she is looking forward to a future without alcohol in Whiteclay. “I rejoice because there’s hope.”

The Lincoln Journal Star reported that rehabilitation specialists and a handful of volunteers were on hand to provide assistance to residents who may need detox assistance. Tribal leaders and activists planned to meet Monday morning to discuss moving forward, though their optimism remains cautious: A court decision in favor of the four stores would open them back up.

Two business owners in the town of Rushville, 20 miles away, told the Omaha World-Herald they had already seen a spike in beer sales, with one gas station reporting a fourfold increase in traffic. Some Rushville residents expressed concern that the store closures would lead to instances of drunk driving on the roads between Whiteclay and Rushville.

Still, many see closing the stores as a crucial first step in fighting alcoholism on the Pine Ridge Reservation, where sales of alcohol are prohibited, and which sits less than two miles from Whiteclay—a town with a population of seven people. And a dry Whiteclay may have appeal for new businesses, too, interested in providing job opportunities and economic development for the area. Family Dollar has already committed to building a store in Whiteclay once the liquor stores are gone.

Activist Olowan Martinez reiterated in a phone call on the day the Liquor Control Commission held their vote that she doesn’t expect the closing of the stores to end alcoholism on the Pine Ridge: “This has nothing to do with the adult drinkers. This has everything to do with those five- to ten-year-olds that have no choice.”