Ella Fassler

I grew up in the country, surrounded by woods—but I didn’t care about my family’s vegetable plot. Now I’m stuck sifting through how-to gardening articles, written for children.

When doomsday finally hit, the “prepper” within me, latent yet aspiring, was disappointed in itself: My pantry was completely empty, houseplants wholly inedible, and medical kit nowhere to be found. But I didn’t swarm my local supermarket to stare at empty shelves. After years of procrastination bolstered by housing instability and general chaos, the pandemic lock-down has created the perfect storm for my first vegetable garden.

Ella Fassler

Fassler potted kale, snap pea, pepper, and cucumber seeds in egg crates.

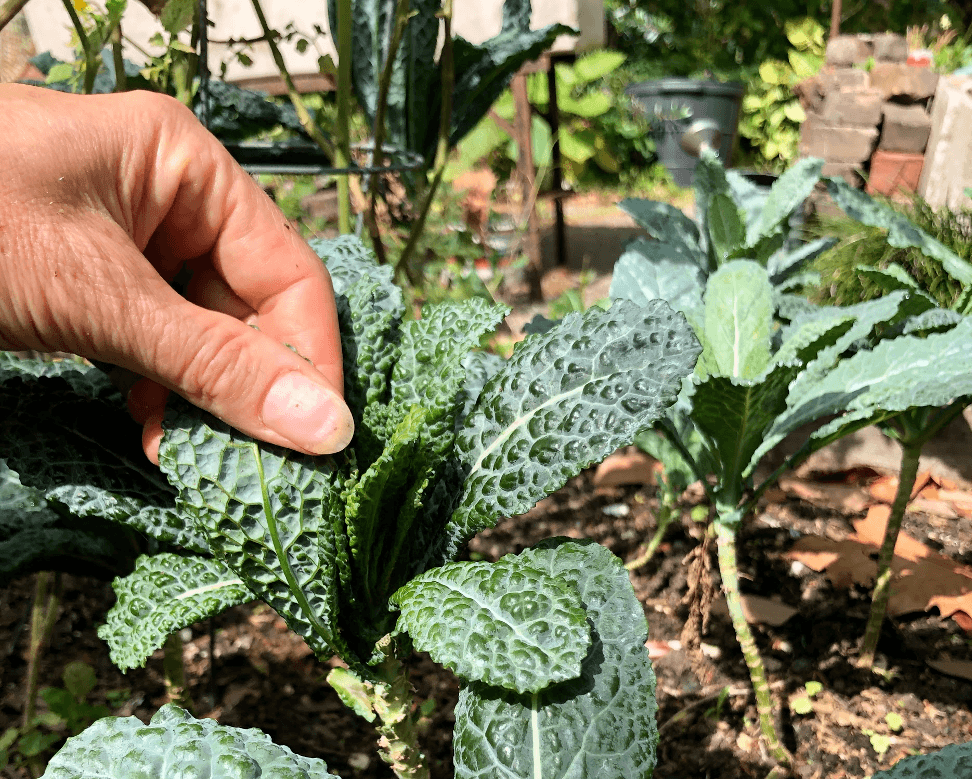

The nuts and bolts of starting such an endeavor were born out of solidarity. In Brooklyn of all places, a radical gardening collective taught me that egg cartons can serve as free, compostable homes for seedlings. So when my neighbor and I simultaneously pulled into the driveway, and he offered a bunch of leftover eggs from his work, I happily agreed. Later that night, I plunged my sanitized hands in a big bag of potting soil my Mom gave me and sprinkled it in the egg crate, along with kale, snap pea, pepper, and cucumber seeds.

Over the next few days, to my delight and horror, the seeds sprouted incredibly quickly. I regret underestimating their tenacity; multiple plants crowded each cup. I’ve been scrambling to transplant them into larger pots indoors, which I have few of, until I can ramshackle some raised beds together.

I grew up in the country, surrounded by woods and a family vegetable garden, so I really should be more knowledgeable about these things. But as a child, nature and chores were often bundled: weeding, piling wood, mucking horse stalls. So I rebelled. Now, I’m stuck sifting through how-to articles which, to add a pinch of salt to the wound, are largely geared toward instructing parents on best practices for teaching young children (“The soil should stay very moist. That’s a new vocabulary word for your child to learn, if she’s not familiar with it already”).

The people who labor to produce our food oftentimes can not afford the food they produce. And many of us here have no clue how to do it ourselves.

For all of the conveniences born out of industrialization and urbanism, the emergence of borderless capitalism has left people alienated from our natural surroundings. This relatively new normal has spiraled to an incredibly non-nonsensical state: The people who labor to produce our food oftentimes can not afford the food they produce. And many of us here have no clue how to do it ourselves.

The pandemic starkly lays bare the danger inherent in this dependency. Stated plainly, if all of your local supermarkets shut down tomorrow you’re probably fucked. We aren’t there yet. Then again the climate crisis has only just begun.

When my seeds sprouted, I texted my Brooklyn-based radical gardener friend with a picture of the baby plants, “They are doing too well. How do I transfer them since all of the seeds sprouted?” She responded, “Today (or around today) is the perfect transplant day, it’s a new moon….”

Truthfully, I’m not keen on the moon’s relevance. Nevertheless, I’d like to start paying attention to the moon’s rhythms, the forage feast around me. Nutrition blooms out of something so tiny. It’s wholesome magic in its purest form. It’s about time we open ourselves back up to its wonders.