The agency previously determined this weedkiller is carcinogenic. Now, without a typical public comment period, farmers got the green light to spray it on crops.

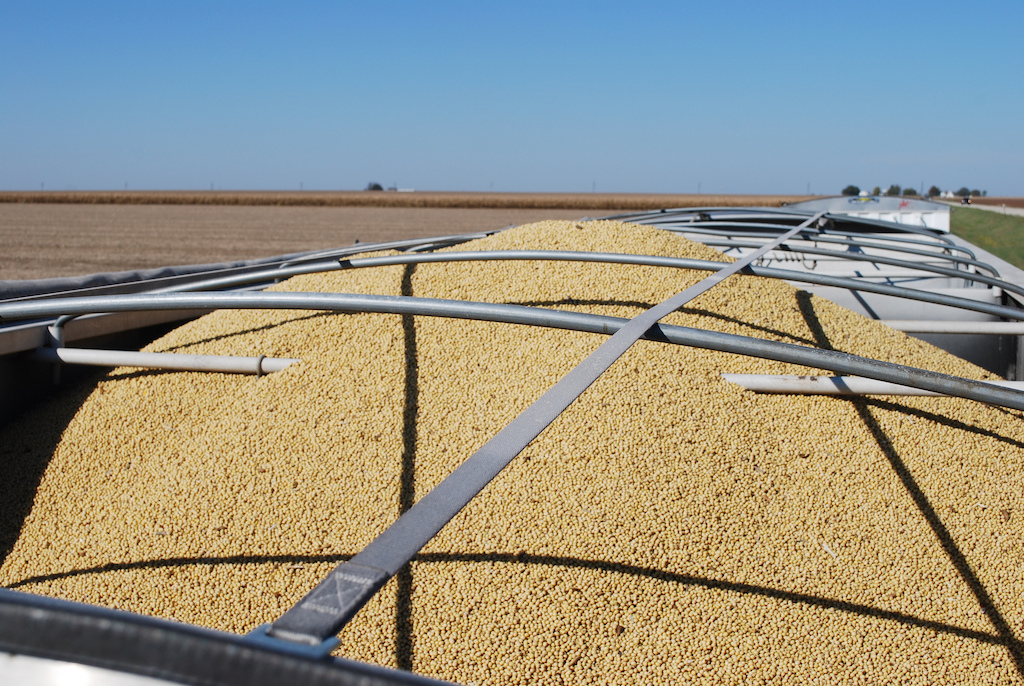

This week, the Environmental Protection Agency announced that soybean farmers in 25 states are now able to spray a pesticide that the agency has determined is likely to cause cancer and drift hundreds of feet from where it is applied.

The move was widely praised by farmers, who view the weedkiller as a new tool in an ever-increasing battle with “super weeds” that have developed resistance to as many as six different types of weedkillers, including glyphosate, the most widely used pesticide in the U.S.

This article is republished from The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. Read the original article here.

The herbicide, isoxaflutole, will be able to be sprayed on soybeans that have been genetically engineered to withstand it. The weedkiller kills broadleaf plants and is already used on corn in 33 states. Isoxaflutole is manufactured by German agribusiness giant BASF and sold under the brand name Alite 27.

Bayer originally commercialized the modified soybeans and herbicide under its LibertyLink system but was required to sell it to BASF as part of the merger agreement when it bought Monsanto in 2018.

In a press release announcing the decision on Monday, the EPA touted the feedback the agency received from farmers on the need for the herbicide.

“The press release caught everyone off guard, we were just waiting for the EPA to open the comment period, and we never saw it.”

But the agency sidestepped the usual public input process for the decision. The herbicide’s registration was opened for public comment, but not listed in the federal register, where agencies provide notice that they are considering opening a new rule. The agency generally publishes significant rule changes in the register.

“The press release caught everyone off guard, we were just waiting for the EPA to open the comment period, and we never saw it,” said Nathan Donley, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity, a national, nonprofit conservation organization.

As a result, all 54 comments received by the agency were praising the technology or asking the agency to allow wider use of the herbicide.

“One side was able to comment, the other wasn’t.”

“Clearly no one from the public health community knew about this because no one commented,” Donley said. “Yet there was all these industry comments, all these positive comments. Someone was tipped off that this docket had been opened. One side was able to comment, the other wasn’t.”

Asked why the agency did not post the notice in the federal register, an EPA spokesman said via email the agency “requested public comment on the proposed registration decision. Based on EPA’s risk analysis and careful consideration of public input, EPA concluded that the application of isoxaflutole on genetically engineered soybeans with certain use conditions could be done in an environmentally-protective manner in certain parts of the country.”

When asked if BASF knew why there was no federal register notice, company spokeswoman Odessa Hines said in an email response there was a 30-day open comment period from Jan. 15, 2020 to Feb. 13, 2020:

Even without significant public comment, the EPA severely limited the areas where the weedkiller can be sprayed because of its likelihood to harm endangered species. The weedkiller, which kills broadleaf plants, is already used on corn in 33 states, but was only approved in specific counties in 25 states.

The herbicide was not approved for use in Illinois and Iowa, two of the nation’s leading soybean producing states. The registration is good for five years.

“This is basically an herbicide that shouldn’t be approved at all for any use. It’s that bad really on both the human health and environmental fronts,” said Bill Freese, science policy analyst at the Center for Food Safety, a national nonprofit public interest and environmental advocacy organization working to protect human health and the environment .

Freese co-authored a comment in 2013 for the U.S. Department of Agriculture when the agency was considering deregulating soybeans genetically engineered to withstand being sprayed by the herbicide. The USDA approved the soybeans. He said he was ready for an EPA public comment period but never saw it.

“They knew this is a bad news chemical, and it was very likely done because they didn’t want to give environmental groups the opportunity to comment on this, so they can avoid scrutiny.”

Among his complaints, Freese said the EPA has determined isoxaflutole is a likely human carcinogen and inhibits a human liver enzyme. Additionally, even very small amounts of the herbicide can cause significant damage to plants and EPA studies show the herbicide is likely to cause harm at up to 1,000 feet. The label is also extremely complicated, requiring farmers to know their soil type and how high the water table is, Freese said.

“It’s outrageous,” Freese said. “They knew this is a bad news chemical, and it was very likely done because they didn’t want to give environmental groups the opportunity to comment on this, so they can avoid scrutiny.”

Donley and Freese said their organizations are reviewing the legal options to challenge the herbicide’s approval. The organizations are already suing over the EPA’’s approval of dicamba, another volatile herbicide sprayed on genetically engineered soybeans.

“Today’s management practices of relying on a single mode of action are not sustainable for long-term control of problem weeds.”

The pesticide will not be widely available until 2021, BASF said in a press release praising the EPA’s decision.

It is unclear how widely sprayed isoxaflutole will be, but Freese and Donley said the product wouldn’t have been commercialized if the company didn’t think it was likely to be used.

Additionally, use is only likely to grow. Right now, about 600,000 pounds of the herbicide are sprayed on corn each year, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

BASF said that nearly three out of four farmers are dealing with glyphosate-resistant weeds and 58 percent are dealing with resistance to other herbicides as well. Weeds have already been documented to develop resistance to the class of herbicide that isoxaflutole belongs to.

“BASF continues to bring new innovations, like Alite 27 herbicide, to market to give growers more operational control over their crops and to help eliminate troublesome weeds in their fields.”

“Today’s management practices of relying on a single mode of action are not sustainable for long-term control of problem weeds,” said Scott Kay, vice president of U.S. Crop, BASF Agricultural Solutions, in a press release. “BASF continues to bring new innovations, like Alite 27 herbicide, to market to give growers more operational control over their crops and to help eliminate troublesome weeds in their fields.”

Bill Gordon, a Minnesota soybean farmer and president of the American Soybean Association, was one of the people to submit a public comment on the weedkiller’s approval.

In the EPA press release announcing the decision, Gordon said the ASA “appreciates the diligence by EPA to provide farmers access to this new tool with the necessary guidance for using it safely to protect people, our wildlife, and the environment.”

Gordon’s home state of Minnesota, along with Wisconsin and Michigan, has already banned the use of the pesticide on corn in many counties due to its likelihood to contaminate groundwater, which is one of the ways the EPA says it can cause cancer.

The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting is a nonprofit, online newsroom offering investigative and enterprise coverage of agribusiness, Big Ag and related issues through data analysis, visualizations, in-depth reports and interactive web tools. Visit us online at www.investigatemidwest.org/