The New Food Economy

On Thursday morning, the popular East Coast fast-casual restaurant chain Dig officially launched a new initiative with a lofty goal: to reduce the vast number of take-out food containers being tossed into New York City’s overflowing garbage bins.

Customers who visit Dig’s Washington Square Park outpost, located at 691 Broadway in Manhattan, will be encouraged to join a new pilot program called Canteen. Those who enroll will install a smartphone app, Canteen by Dig, and consent to a fee of $3 a month for the service. In return, they’ll be able to take their lunch with them in a hard-shelled, reusable bowl made from black melamine, complete with a white plastic lid.

Dig’s Washington Square Park outpost, located at 691 Broadway in Manhattan will be the first store to pilot the new program Canteen.

Dig

A few take-out restaurants across the country already sell plastic bowls to customers for re-use in their stores. But while those bowls typically stay with the customer after a meal, Dig’s bowls function like boomerangs: After short trips out into the world, Dig wants them to return home again. Patrons who whisk containers away to the office, to their apartment, or to the park can swap out used bowls for fresh ones during each subsequent visit. The best part, as far as customers are concerned? Dig will handle the task of washing all those dirty dishes. That makes it the first New York City restaurant to offer a “closed-loop” program for take-out containers, a significant undertaking that will require the chain to store, clean, and maintain a fleet of reusables.

The effort, while still nascent, will set Dig at stark contrast to most of its competitors. Fast-casual restaurants, the counter-style, quick-service chains that emulate the speed and simplicity of Chipotle, tend to generate huge amounts of solid waste. They’re typically small, limited-seating eateries without dishwashers or extra storage space, designed to serve busy customers who take meals with them. (Dig estimates that roughly 80 percent of its customers eat outside its restaurants’ walls.) As a result, the industry relies heavily on single-use containers, the easiest kind of packaging for diners to carry off the premises. By the time those receptacles do get thrown out—usually far from the restaurant, in an office building or sidewalk trash can—the waste generated is no longer technically the restaurants’ problem.

Dig’s new app, Canteen by Dig, allows members to enjoy meals in a rented reusable container

Dig

It’s not that restaurants have simply been bad actors here. In fact, many have tried to use more sustainable throwaway containers, often paying handsomely to do so. But the limitations of the single-use model are becoming more apparent. With China rejecting shipments of recyclable materials from countries across the globe, many traditional plastics are getting landfilled. Meanwhile, plant-based PLA plastic bowls are a source of confusion for consumers, who tend to throw them in the bin with plastic bottles, even though they can’t be traditionally recycled. While technically compostable, multiple sources tell me that PLA plastics often don’t break down as well as advertised, which means many composting facilities reject them and they end up being garbage anyway.

In recent years, compostable bowls made from molded plant fiber have been a seeming bright spot. Still, while those bowls break down more easily, and are less environmentally costly to produce, they come with problems of their own. In practice, fiber bowls rarely end up being composted; most regions in the U.S. simply lack the infrastructure to collect and process them. Some restaurants, including Dig, have toiled to create ambitious composting programs, and reporting from The New Food Economy’s Karen Stabiner shows that they can be overwhelmed by the task’s logistical complexity.

More recently, plant-fiber bowls have been shown to have problems that are even more profound. This summer, I reported that virtually all fiber bowls have been treated with PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, a broad class of fluorinated “forever chemicals” that don’t break down in the environment and have been linked to troubling health effects. For reasons I explain in my investigation, these bowls are more likely to contaminate compost than increase soil health. In fact, the last thing you want to do is spread PFAS-laden compost on a crop field.

In my interviews with Dig’s leadership, it sounded like the company has gradually come to embrace a difficult truth: Single-use containers are never going to be sustainable. It may never make environmental sense to handle a piece food packaging for three minutes and then throw it out. And if that’s the case, restaurants that claim to think holistically about the food system should—and perhaps even have an ethical obligation to—find a way to bring reusable products back into the American dining experience. No matter how complicated that challenge may turn out to be.

Both Adam Eskin, Dig’s founder and CEO, and Elizabeth Meltz, Dig’s senior director of environmental health, describe a perspectival shift that has taken place at the company over the past few years. It’s a realization that the farm-to-table ethos doesn’t go far enough. That well-known formulation implies the table is an end point, downplaying the environmental importance of each meal’s aftermath.

Dig’s founder and CEO, Adam Eskin. At right, Dig’s senior director of environmental health, Elizabeth Meltz

Dig

“Over the last eight years, we’ve done a lot of work on upstream agricultural practices, farming, everything that goes into getting the food from the farm into the restaurants and onto our desks,” says Eskin. “As time has passed, we’ve started to shift that focus.” Meltz, who joined Dig in July 2018, says she found the company wanted to give its dishware the same attention as its carefully-sourced ingredients.

That won’t be easy. According to Eskin, a Dig restaurant can easily go through 1,000 single-use bowls per day—a “good, round number” that he says reflects the general order of magnitude. That means Dig’s 24 Manhattan restaurants can use an astounding 24,000 molded fiber bowls daily (all of which have been treated with PFAS). And Dig is still a small company, a drop in the bucket when you consider the bowl-food genre’s massive dimensions.

There are other regional startups to consider, the Sweetgreens and Just Salads. There are food halls. There are national titans like Chipotle, which seem to have a restaurant on every block. There are restaurants that do a swift home-delivery business, meals demanded by thumb via smartphone app. Taken together, it all makes for an unfathomable daily crush of garbage—even if you’re looking only at fast-casual restaurants in one major American city.

This is the daunting reality that Dig aims to address with its Canteen program. For reasons I’ll explain, the company hopes its modest, single-store pilot will grow beyond its limited scope into a model that enough New York City restaurants participate in to make a meaningful dent in the city’s food packaging waste. That might sound unrealistic, were it not for the fact that it’s already happened elsewhere—across the country, in Portland, Oregon. The story of how a small, West-Coast startup ultimately provided the technology and blueprint for Canteen by Dig suggests that Portland and New York are not as different as they might seem, and that it really may be possible to get takeout without the trash.

—

When Dig first started looking into reusable to-go containers, only one approach existed in New York City: the so-called “resale” model. Pioneered by the New York-based fast-casual chain Just Salad in 2006, this model entails selling a bowl to customers, who then become responsible for shlepping it back and forth from the store to work, to home, and back again.

Today, that approach seems to have had success. According to Sandra Noonan, Just Salad’s chief sustainability officer, 30 percent of the company’s in-store customers use the reusable bowls—enough to divert a projected 75,000 pounds of waste from landfills in 2019. While that’s an admirable achievement, the model isn’t without its challenges. Due to New York City health codes, Just Salad employees take extra precautions to make sure that customers’ bowls, which haven’t been commercially sanitized, never make physical contact with the workers or the serving counter. The resulting process requires transferring the bowl from customer to server using a pair of tongs, and sliding bowls along the counter on special black plates, among other idiosyncrasies. “It involves a high standard of training,” Noonan says.

The fact that customers end up being the primary custodians of their bowls, too, presents issues. “Aside from the hardcore green consumers, and maybe even the slightly less hardcore green consumers, most people don’t want to be bothered carrying around cups or containers,” says Rich Grousset, a sustainability consultant who works for ThinkReuse, a New York-based firm.

According to Laura Rosenshine, co-founder of Foodprint Group, a zero-waste consulting company hired by Dig to explore a shift to reusables, Dig leadership considered both the resale and exchange options. “They felt like the exchange model was easier, because it actually required less of their employees to follow this special procedure,” Rosenshine says. “They were like, ‘We’re not gonna have an easy time meeting demand at our service line during lunch, if we have to keep passing this bowl and being very careful about the way that we touch it and hold it.’”

But earlier this year, Dig stumbled on another model that could sidestep those issues—though it would come with its own set of new complexities.

Go Box provides reusable clamshells to over 100 restaurants in Portland, Oregon, tracking their whereabouts by smartphone app

Go Box

In 2010, a Portland resident named Laura Weiss noticed something unfortunate: The Oregon city’s vibrant culture of food-cart “pods,” large communities of mobile-food marts, was generating a whole lot of trash. Weiss had a perfect background to take the problem on. She’d been a toxicologist at Washington State’s Department of Ecology, a program director for the Oregon Environmental Council, and a regional manager for Aramark, one of the nation’s largest institutional food-service providers. In 2011, she founded Go Box, a company that would go on to do three things: provide a consistent source of reusable clamshells to local residents, take over the supply and washing of those containers for restaurants, and provide the technological infrastructure that made the whole system work.

Weiss retired in 2018 and sold the business to its new CEO, Jocelyn Quarrell, who tells me that its impact has only grown since then. Today, Quarrell says, the business has 105 vendors in Portland, a diverse group that includes brick-and-mortar restaurants, food carts, numerous locations of a local grocery chain, and even a movie theatre. Over 3,000 members regularly use the service. And internal data show that the program prevented more than 260,000 single-use containers from being thrown away since 2011. That’s a significant amount of trash avoided, even if it’s still less than a single Dig location would generate in one year.

Here’s how the program works for eaters. Subscriptions start at $21.95 a year for the right to rent one Go Box container, a translucent, polypropylene clamshell made out of polypropylene #5, a recyclable plastic that is dishwasher-safe and BPA-free. Those who want to use more than one container at a time can pay $40 a year to rent up to four simultaneously. Provided they don’t take out more than their allotted number of containers, members get unlimited access to the Go Boxes stocked by participating vendors. When their meals are finished, they can drop off their clamshells at one of about 30 drop-off points located at businesses around the city. (Not all participating restaurants are also drop-off points).

Not all of Go Box’s participating vendors are restaurants. It also serves, for example, numerous outlets of New Seasons Market, a local grocery chain

Go Box / Facebook

Perhaps more interesting—and more relevant to Canteen by Dig—is how the program works for vendors. Restaurants and other eateries pay a one-time setup fee, including the cost of preparing a drop-off point for eateries who want to host one. From there, the costs are straightforward. To have their inventory restocked, vendors pay a price of 25 cents per container, and 15 cents per cup.

That might sound expensive. But Quarrell insists that those prices are comparable to what restaurants already pay for high-end, single-use items.

“For the vast majority of our food vendors, the cost is not a barrier, and it ends up being mostly cost-neutral for them,” she says. “Many of them are paying similarly, or maybe even more, for quote-unquote ‘compostable’ containers.”

This math checks out. On its website, the food-service packaging company World Centric, which supplies several leading fast-casual chains, sells 500-packs of 24-ounce molded fiber bowls for $118.50. That works out to nearly 24 cents per bowl—a pretty penny, considering that bowls like these, though marketed as “compostable,” are also treated with PFAS, and probably shouldn’t be composted. The Go Box version costs only about $0.01 more per use. For some vendors, the knowledge that they’re not generating refuse, or discharging worrisome chemicals into the environment, may be well worth the modest increase in overhead.

Earlier this year, Laura Rosenshine, the food waste consultant who works for Dig, introduced Quarrell to the company’s leadership, hoping that Go Box might provide the tech infrastructure that could power Dig’s reusables pilot. There was at least one precedent. In 2014, GoBox licensed its technology to a separate private business, Go Box SF Bay. Today that company works with dozens of vendors in California’s Bay Area, and operates seven drop-off sites between San Rafael and Palo Alto. It pays Go Box only for access to its technology, and runs the rest itself. If the model can work in San Francisco, why not in New York?

That’s the question that Dig will try to answer, starting this week. For now, it licenses the technology for its Canteen by Dig app from Go Box, and will handle other duties—namely stocking and washing its containers—itself. Since Dig already offers guests the option to be served in non-portable reusable bowls, it has dishwashing infrastructure on site. The main thing Dig customers will have to do differently is flash a screen on their Canteen app that says “good to go”—letting employees know that they’re enrolled in the program, and don’t already have a bowl checked out.

Eskin says that he’s not sure how soon the Canteen program will become available at Dig locations beyond 691 Broadway. Ultimately, though, he hopes the program will interest other restaurants, which can also license Go Box’s software. If enough people get involved, maybe a private company—or one of the restaurants themselves—will start to build communal dishwashing facilities, the kind Go Box already operates in Portland.

That ambition makes sense, and not just because of the extra work of washing containers. For now, Canteen members can return their containers only at the one restaurant that offers them—the Dig near Washington Square Park. But Eskin and Meltz imagine a future where those same customers can return their bowls, and pick up replacements, at Sweetgreen, or at Just Salad, or at Chipotle. With this approach, there may be strength in numbers.

“When chefs and general managers and operators wake up and go to work every day, there’s just a lot to think about,” Eskin says. “It’s what we call ‘shift happens’—you know, you have to put a call out because an oven goes down. What we’ve experienced, whether it’s introducing new ideas or new technologies, is that the friction and complexity of this business makes it harder to bring these things into existence.”

Change, in other words, doesn’t come easily in restaurants. “But because of where we’ve been able to get to as as a business, we do have the resources, we do have the desire, and we can get started,” he says. The company received $20 million in investment money earlier this year, including $15 million from Enlightened Hospitality Investments, which is partly owned by Shake Shack founder Danny Meyer’s Union Square Hospitality Group. The company, you might say, is in a position to experiment.

—

Often, in situations where business stands in the way of a social good, a familiar reason is given: It’s too expensive to do the right thing. In this case, conventional wisdom holds that many restaurants with take-out operations must use disposables, because reusable dishware is too costly. The strange thing is that the opposite seems to be true. The available evidence is limited, but all of it suggests that reusables can actually save restaurants money.

As a program manager at Rethink Disposable, a California-based initiative of the nonprofit environmental group Clean Water Action, it’s Samantha Sommer’s job to help wean eateries off single-use items. She provides the expertise and technical assistance cafes and restaurants need to switch to reusables, while pitching business owners on the potential benefits of doing so: happier customers, more fulfilled staff, improved environmental impacts, and extra money in the bank. In her experience, though, many restaurants don’t choose disposables as a way to cut costs. Instead, they choose to spend more money than they need to.

“Our experience working with thousands of food operators is that they want to do the right thing. They’re actually spending more—like 10 to 20 times more per item,” she says, comparing the cost of high-end, plant-based products to cheaper plastic and styrofoam offerings on the market. “But we tell our business owners that, when they’re investing all this money to procure potentially 30 different types of disposables each week, they’re really throwing all that money in the trash. The kicker is that they pay even more money to haul all that trash away. And the worst part about it, the real sting when the band-aid comes off, is when we say: ‘Yeah, I hate to tell you, but in this city, those cups aren’t recyclable. And they don’t want that compostable material you’re using. Oh, by the way, did you know that this compostable material tests really high for having perfluorinated compounds?’”

Sommer says it’s never easier for business owners to hear their good intentions were misplaced, and that their money was likely squandered. But there is a silver lining here. The restaurants spending the most on disposable products have the most to gain, financially, by abandoning them.

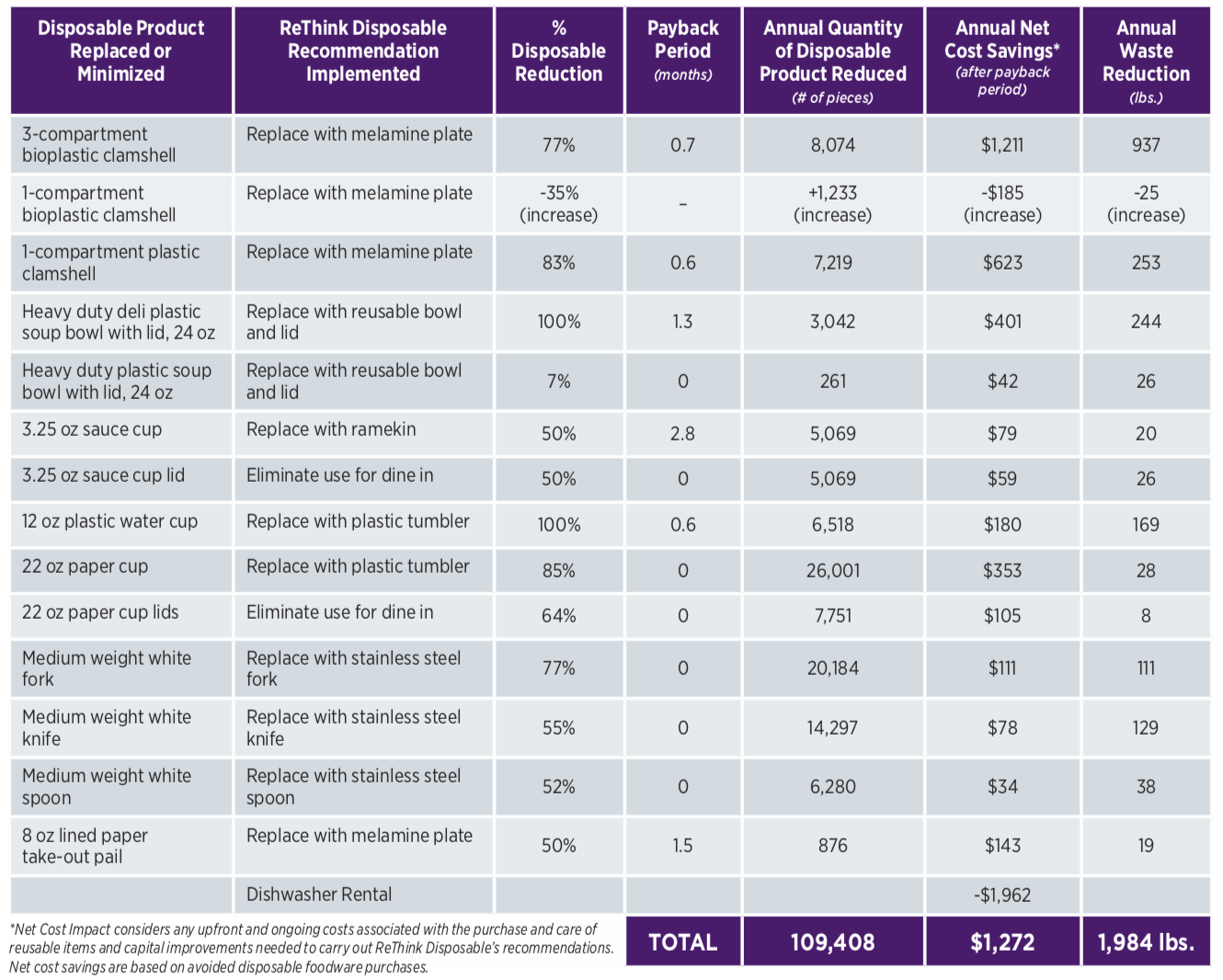

To illustrate this point, Sommer shared 25 Rethink Disposable case studies with me. These detailed documents itemize specific costs related to disposable goods, from bowls and cups and cutlery to packets of iodized salt. The results are striking. Even single, standalone restaurants can divert metric tons of trash from the landfill annually. Doing so can also save them thousands of dollars a year. These restaurants don’t seem to offer reusable take-home containers, in general. But the fact that they can save money by pivoting away from disposables still broadly illustrates the point: Single-use items cost restaurants dearly.

A taco spot in Los Angeles saved $416.18 in one year, and cut over 200 pounds of trash, simply by giving guests metal cutlery and reusable glasses for soda. That’s the simplest example. More ambitious makeovers had more impressive results. A food truck in Emeryville saved $2,028 mostly by switching out its disposable trays and paper wrap with reusable products, diverting over 2,500 pounds of waste. A 35-seat cafe in San Francisco saved $6,898.82 by ditching disposable cups, cutlery, straws, stirrers, hot lids, and cup sleeves, diverting more than 2,000 pounds of waste. A 24-seat Filipino restaurant in Sunnyvale saved $22,122.36 in one year by opting for reusable plates, bowls, flatware, and sauce dispensers, diverting more than 150,000 disposable items from the landfill.

Then there’s Bon Appétit Management Company—a subsidiary of Compass, the largest institutional food-service provider in the world. Bon Appétit saved $157,883, and prevented 26,926 pounds of waste in one year by implementing a range of straightforward policies at a cafe on the University of San Francisco campus, including replacing disposable salad bowls with reusable alternatives, and reducing the availability of disposable cutlery.

The surprising thing is that these savings all include the cost of investments made to prepare for the changeover, including additional expenses like new inventory, increased water usage, and added labor. Most newly purchased reusable stock paid for itself in a month or less, according to the case studies. Though Sommer says that improved practices can typically be implemented with existing staff, I found one case study where a 22-seat Hawaiian barbecue restaurant hired a part-time dishwasher to help with extra dishes. Even with that added expense, the company saved over $1,200 a year.

Excerpt from a Rethink Disposable case study, itemizing the savings that a California restaurant saved by switching to reusable products

Rethink Disposable

“Some business owners shriek when we say ‘You might want to hire a dishwasher,’” Sommer says. “But even with that cost, you’re still saving money and you’re creating a job.”

Why would any restaurant ever use disposables, I asked Sommer, if the benefits of reusables are that thunderingly obvious? She stipulated that she can speak only about the experience of eateries in California, where several specific factors come into play. There are strong environmental regulations that make it difficult, and expensive, to generate trash, for one thing. The state’s environmental progressivism is also embedded in California culture, which may make some business owners and customers more willing to modify their behavior.

“It’s a beautiful program,” she says. “But the thing is, it requires a very in-depth, unique support process for every single business. Each one is going to require something different. So it’s hard to guess what the results in a city like New York might be.”

In New York, things may very well be harder. Just Salad’s Noonan says that her company has had to offer customers an incentive to make the program work. Anyone using a reusable bowl gets a free topping of their choice, a giveaway that is in no way offset by the price of the $1 bowl. Ultimately, she says, the bowls end up becoming a kind of loyalty program, driving enough repeat visits to make the lost revenue more than worth it. But while taking that strategic risk might look smart now, it was a gamble.

“You have to do the work of figuring out the economics, and, and being comfortable with the loyalty benefits of the program, offsetting the cost of administering this kind of a program,” Noonan says.

In other words, though reusables may ultimately save money, they also require creativity, coordination, and an appetite for risk. They’re not an easy way out, so much as a choice to take a harder, more rewarding path. Customers, in the end, must also be convinced to join restaurants on that harder, better journey. And that may be where the trouble really lies.

—

In order to understand how we got here—how single-use disposables became the norm, to the apparent detriment of the entire restaurant industry—it helps to understand the history of recycling in the U.S. The big push toward recycling in the 1970s was never really about environmental benefits or sensible economics. Instead, it was the way that some of the world’s biggest polluters attempted to launder their own reputations by putting the ethical onus of packaging waste on the American populace.

In a 1970 meeting with soda industry leaders, the president of the National Soft Drink Association explained how the optics of America’s growing litter problem posed an existential threat to business:

“It is your and my product that may lie along the side of the road, inviting public wrath,” he told his colleagues. “It is our trademark on it and it carries our product…. [The public is] going to be concerned with the final social consequence of your and my enterprise, and they are going to expect us to account for that consequence.”

Those remarks, as transcribed in the meeting’s minutes, were unearthed by Ohio State University historian Bartow J. Elmore, in his 2014 book Citizen Coke: The Making of Coca-Cola Capitalism. From there, Elmore lays out the facts in devastating detail: It was not eco-conscious hippies who lead the charge for recycling programs, but soft drink manufacturers who feared an angry public would start asking them to account for the environmental consequences of their business model.

Recognizing their vulnerability to criticism, soft drink manufacturers inundated the American public with advertisements extolling the benefits of recycling. They used their clout to fight bottle and can taxes, legislative measures that would have made the social cost of their products more apparent, despite clear evidence that such efforts would cut waste. And they lobbied heavily for curbside recycling programs, which Elmore says industry “pitched as a fix-all, rather than as a complement to additional waste reduction initiatives.” Elmore argues that these programs were attractive to lawmakers because they didn’t impose any upfront costs on American citizens. Unlike bottle taxes, this solution was unlikely to draw added scrutiny or public ire. And so, the public was never really forced to reckon with the impacts of its soda habit.

The trouble was that recycling programs didn’t really reduce waste; they only mitigated and disguised the extent of the damage. Even in the early 1970s, that writing was already on the wall. “Recycling is so far not paying its own way,” The New York Times reported in 1972. “And there is a growing belief that it will be years—if ever, before it makes any major dent in the nation’s mounting piles of solid wastes.” Today that vision has come to pass. Even now, after years of effort and billions of dollars spent, we still cannot recycle quickly or efficiently enough to reduce the staggering bulk of waste.

The history Elmore tells is instructive, as the restaurant industry has followed a parallel path. According to Grousset, the sustainability consultant, the problem really crystallized after World War II, when the explosive growth of cheap plastics and the rise of the automobile hit America at the same time. Americans wanted to take burgers and milkshakes with them in their cars. For a while, restaurants were more than happy to oblige them. But as the social and economic costs of that approach have grown, restaurants have been unwilling to admit that throwaway consumption is the fundamental problem. Instead, like the soft drink industry, they’ve tried to disguse the issue through greenwashing: by switching to single-use items that are ostensibly recyclable, supposedy plant-based, theoretically compostable. The suggestion is that, by stocking these products, a restaurant has already done its part.

The civilian eater, it turns out, is eager to believe this lie. It reinforces the comforting notion that the woes of over-consumption can be solved through new and better technology, and that our convenience comes without added costs.

Those who enroll in Canteen will receive a hard-shelled, reusable bowl made from black melamine, complete with a white plastic lid.

The Counter

But it’s possible that Canteen By Dig—the latest development in a sequence that started with Go Box, and Just Salad before that—represents the beginning of a fundamental realignment. These programs proceed from a different starting place: the assumption that restaurants bear some responsibility for the trash they put into the world. The open question is whether customers are ready to accept that responsibility, too. Because nothing is ever easier, in the short term, than buying something and quickly throwing it away.

I was curious about how Dig settled on the $3 figure, the amount the company will charge customers to use Canteen each month. And Eskin’s response is surprising. The number wasn’t really based on a projected break-even point.

“You know, we actually talked about making the program free,” he says. “But based on the studies that are out there, we thought this could actually work against getting the program off the ground. If there’s no price associated, then there’s no incentive that supports returning the bowl, or that supports active participation. So we did our best to come up with a number that we thought was a nice in-between to satisfy both sides.”

Assigning value to a common convenience that has long been free, the step soda makers were never willing to take, is a gamble, and a dare. It’s an invitation to make a meal just a bit more mindful, to break easy habits of consumption and replace them with a routine that requires more of us, in the name of being better. We’ll see if New York—at least the little swath of it near Washington Square Park—is up to the task.