In 2016, nearly 80 percent of California voters said they’d support health warning labels on soda advertisements in response to a survey conducted by Field Poll, a public research organization with a West Coast bent. The next year, Californians reaffirmed their support of policies aimed at reducing sugary beverage consumption: 62 percent of San Francisco voters said “yes” to a tax on a sugary beverages. On the same day, the cities of Oakland and Albany approved taxes with similarly wide margins.

Yet despite overwhelming public support, both policies have been stymied amid intense industry blowback. In 2018, then-Governor Jerry Brown signed legislation preventing cities and counties from imposing new soda taxes for the next 12 years. And last week, a federal appeals court unanimously delayed the implementation of San Francisco’s 2015 law requiring health warnings on ads for sugary beverages.

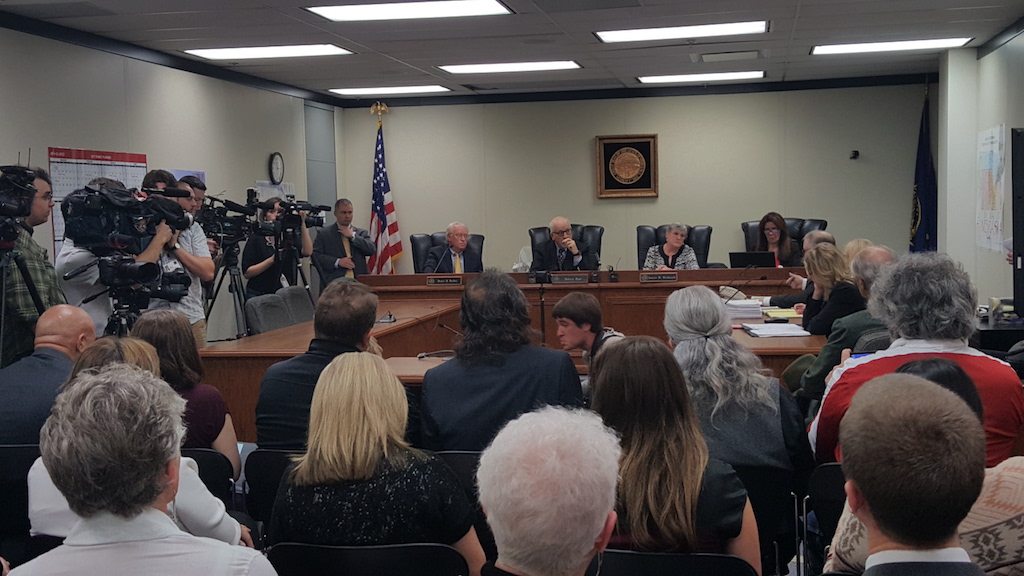

The 11-member court voted to grant an injunction to the American Beverage Association, a beverage industry trade organization that’s challenged the rules. This means the law won’t go into effect as long as the case is still being litigated. The court specifically took issue with the city’s requirement that warnings take up 20 percent of the space on any ad, calling the city’s argument for this proportion “unpersuasive.”

The warning would’ve applied only to print ads on billboards, in stadiums, on transit shelters, in buses and cabs, and so on. It did not include advertising in magazines, on television, on the internet, or on the drink containers themselves.

It’s unclear what kind of impact this warning might have had on sugary beverage sales. A 2018 study by researchers at Harvard University tested various types of sugary beverage warning labels at a Massachusetts hospital cafeteria over a 14-week period. They looked at calorie labels, text-based labels like the one proposed in San Francisco, and a graphic label that included text and pictures of decaying teeth, the naked upper body of an obese person, and a photo of a person getting an insulin shot.

Unsurprisingly, the graphic warning labels were the most effective, resulting in a 15 percent reduction in sugary beverage purchases. Tooth decay is not exactly appetizing.

But people in the cafeteria seemed to ignore the text-based health warnings and the calorie labels. Neither group saw a statistically significant difference in purchasing behavior from the baseline measurement.

In response to the court’s decision, a spokesperson for San Francisco’s City Attorney told NPR that the court’s decision was based solely on the size of the warning label, adding that the court “suggested” 10 percent would be sufficient. “We’re evaluating our next steps in light of this decision,” she added.

Correction 2/20/2019: We have updated this story to clarify that the court granted a preliminary injunction. We regret the error.