A surprising aspect of the contentious debate on the tip credit—the mechanism that allows restaurateurs to pay workers less than the minimum wage, provided they make up the difference in tips—has been the rush of servers who have come forward to say that raising wages would actually hurt them. The counterintuitive pitch is being aired consistently by servers at public hearings across the country: By paying us more, you’re really paying us less.

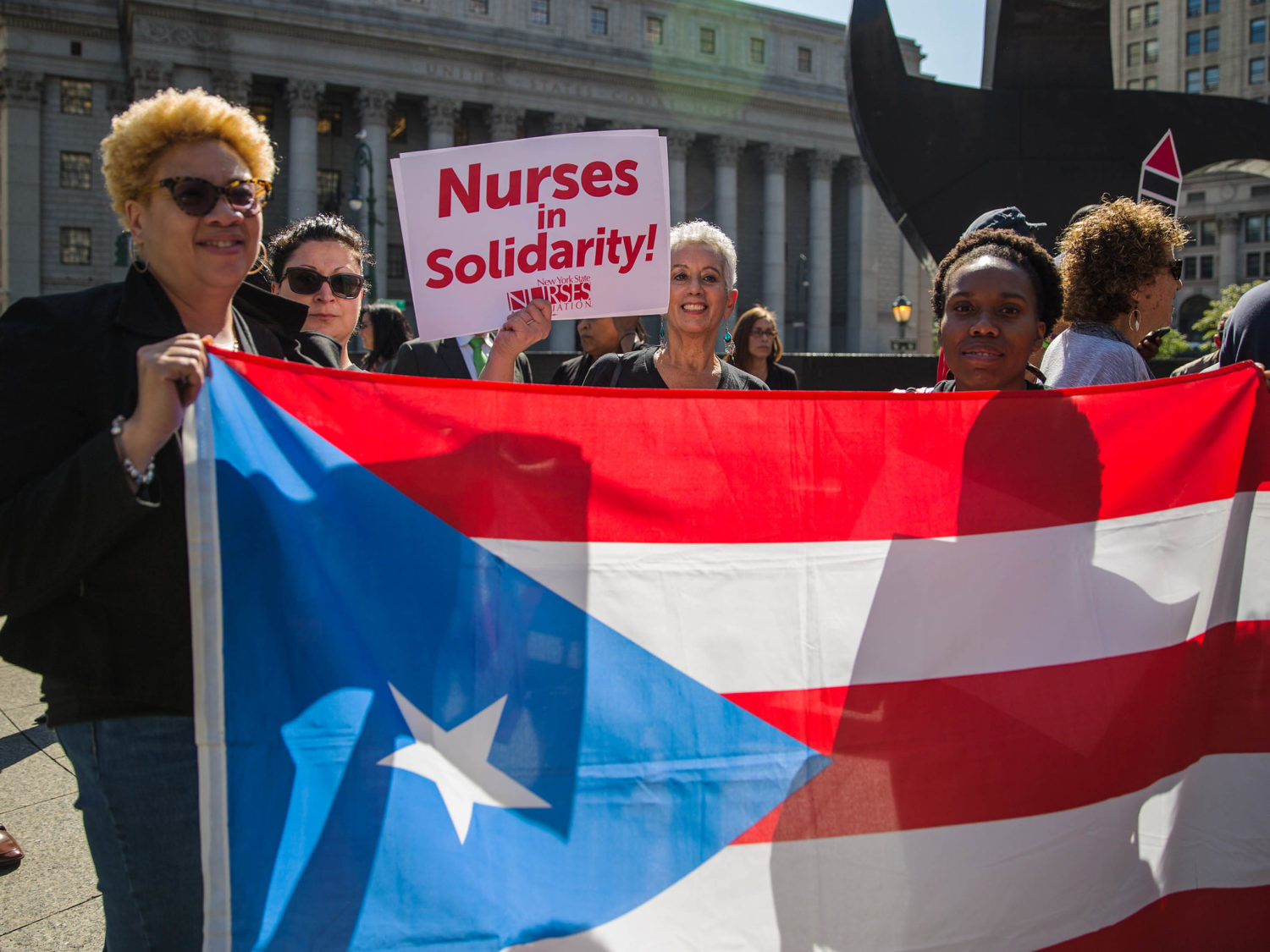

That grievance was aired, once again, this week in Washington, D.C., where the City Council called 253 people, including some waiters and bartenders, to testify about repealing the tip credit.

Ryan Aston, a public witness, warns that “15 dollars per hour is actually zero dollars per hour if the job doesn’t exist,” arguing that higher tipped minimum wage would cause restaurant layoffs.

— Leah Douglas (@leahjdouglas) September 17, 2018

The servers’ argument, which also surfaced this summer at similar hearings in New York, tends to go something like this: If you raise their wages, the restaurant’s payroll goes up. When the payroll goes up, menu prices increase. When prices go up, price-conscious diners stay home. Fewer customers means fewer tips. That’s less money for the servers, and less business for the restaurant. Eventually, the logic goes, restaurants have to lay off staff, or close down.

But does that argument actually hold up? For insight, look to Minnesota, which successfully eliminated the tip credit—first by reducing it to 20 percent as part of a 1977 minimum-wage bill, and then, as part of a 1984 bill, by phasing out the tip credit entirely in 5-percent increments over four years. (The state is now considering reinstating it.) A review of the archives of the Star-Tribune, Minnesota’s largest daily newspaper, reveals that the arguments people made for and against the tip credit some 40 years ago are the same ones we’re hearing today.

At the time, supporters of the tip credit, whose vocal proponents included lobbyists from the Minnesota Restaurant Association, restaurant owners, and even stock analysts, said killing the tip credit would be bad for the industry.

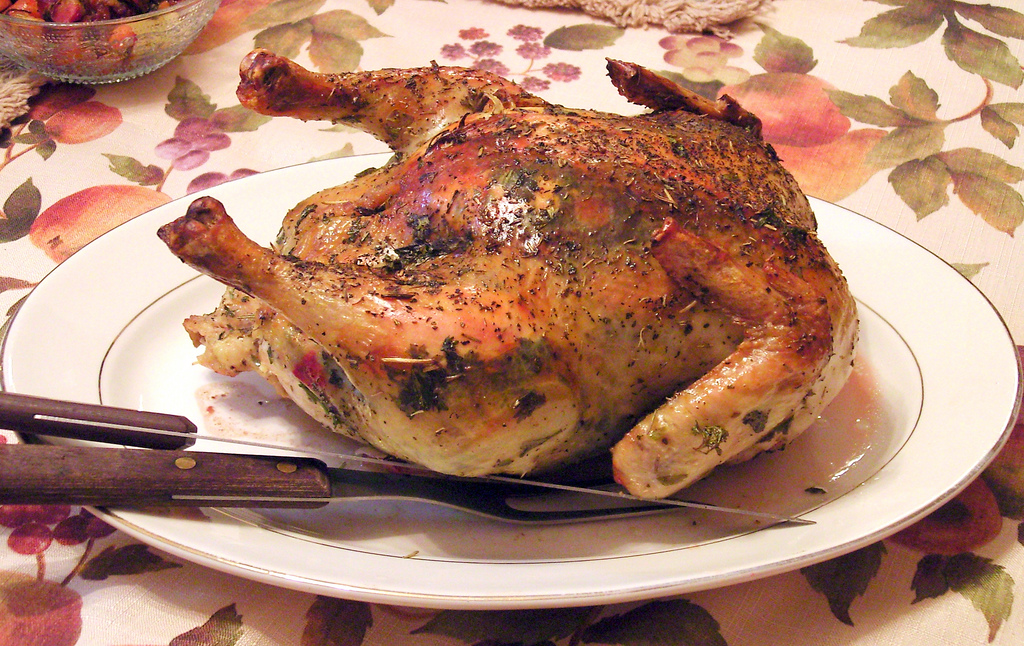

Prices would rise. “Imagine how high the restaurant menu prices would have to be raised to pay the waiters and waitresses equal to the amount a good one receives in tips,” wrote June and Bob Abrahamson, owners of The Soda Fountain restaurant, in a letter to the editor in 1977. “If this change in the law does pass, those legislators would probably be the first to complain about the price of a $3 hamburger.” (That’s over $12 in 2018.)

Jobs would disappear. When the state passed the tip credit reduction in 1977, a state restaurant lobbyist said the higher wages would result in fewer jobs. “I’m afraid everyone will be taking a very close look at their part-timers,” Chum Bohr told the Star-Tribune. “Those 5- or 10-hour-a-week jobs are the ones that may well be eliminated.”

The industry would tank. Around the same time, a Democratic Congressman from Pennsylvania, John Dent, had introduced a federal minimum wage bill that would eliminate the tip credit across the country. If it passed, a trade publication predicted a loss of 190,000 jobs—due solely to the lost tip credit—while an Associated Press financial columnist advised restaurant investors to “run for your lives and don’t come back.”

Restaurants pressed their waiters and waitresses into service. When a bill was up to reduce the tip credit, the Star-Tribune reported that a Minnesota Restaurant Association lobbyist called a manager at a steakhouse in St. Paul to convince their servers to oppose the bill; one waitress happened to be the 22-year-old sister of a state senator who backed it. (The National Restaurant Association funds waiters to publicly support the tip credit to this day.) Several years later, Ember’s, a once-thriving restaurant company, paid a server named Karen Schmidt to attend a wage hearing, where she testified that she’d lose customers if menu prices were raised.

Even after Minnesota repealed the tip credit in 1984, representatives of the hotel, restaurant, and resort industries continued to press legislators to bring it back. The next year, in 1985, a state representative introduced a bill to freeze the tip credit at 15 percent, saying that prices at Minnesota resorts were sure to go up without the credit, and that the state would lose business to resorts in neighboring Iowa or Wisconsin. The attempt to stop the tip credit phase-out failed by a vote of 64 to 59.

And then again, in 1990, hospitality industry lobbyists pushed a proposal to restore the tip credit, saying that abolishing it had caused animosity between servers and kitchen help, who got no tips unless waitstaff pooled and shared them. (Mandatory “tip-pooling” had been banned as part of the 1977 legislation.) That, too, died in a senate subcommittee. What was the state’s solution to what pundits today still call the problem that’s tearing restaurants apart? “There’s a simple answer to that,” said a state senator from Minneapolis. “Raise the cooks’ wage.”

In the end, none of the doomsday scenarios actually played out. After the tip credit was repealed, Minnesota’s restaurant industry didn’t collapse the way it was expected to. Far from it. Between 1987, when the state’s tip credit was 5 percent, and 1992, when servers were on the regular minimum wage, the state added 716 bars and restaurants and 5,778 jobs, according to economic census data. At the same time, annual revenues increased by $816 million. Granted, growth was larger in the prior period—between 1982 and 1987, when the tip credit was still around, the state added many more restaurant jobs—but it was growth nonetheless.

So it wasn’t the servers who took the hit. Nor was it diners. If anyone, it was the owners. After the state got rid of the tip credit, sales and jobs continued to rise, but so did the payrolls—jumping by $270 million, or 40 percent, which was higher than almost any other retail sector. That might seem like a daunting statistic for the cash-strapped owner of a restaurant. But it also suggests that restaurants began paying their employees fairly, according to the rules everyone else follows. Today, restaurants in Minnesota appear to be doing fairly well: Employment in the sector has nearly doubled since 1990, according to state economic data.

What’s the takeaway from taking away the tip credit? If there’s pain in the industry, it’s temporary. And that ending the tip credit doesn’t herald the end of restaurants, despite grave pronouncements to the contrary.