Getty Images/EyeEm

How do today’s culinary guides reflect—and reframe—ideas about Jewishness?

Writer Charlotte Druckman and editor Rebecca Flint Marx are both Jewish journalists living in New York City. And they both love cookbooks. So they convened to have a conversation about recent-ish Jewish cookbooks—and ultimately, what it means for a cookbook to make a claim about its very Jewishness.

As secular women and curious eaters exploring their own relationships to Judaism and its varied food cultures, they have each considered this question before. Druckman, editor of the book Women on Food, grew up in what she describes as the “very WASP-y Upper East Side” of New York, attending an equally WASP-y all-girls school. Her atheist mother had left Reform Judaism but wanted to make sure her children connected to their heritage and had some religious instruction. For Druckman’s father, that meant many years of Hebrew school. So her early relationship with Jewish foods was mostly inherited through her father’s memories and some contact with New York’s once-immigrant community of Eastern European Jews.

Flint Marx, who works as an editor for Eater, was born in Birmingham, Alabama, where her mother’s family had roots dating back to the 1800s (yes, Jewish communities have long roots in the South). When the household moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, the self-confessed “Lender’s bagel kid” learned about Jewish deli foods from the famous Zingerman’s Delicatessen. Her awakening was a family affair. Her dad was an Army kid who lived in Germany in the 1950s—not a particularly good time or place to explore his Jewish identity. Later, when she and her sister were old enough to bat mitzvah, the entire family did it together.

Druckman and Flint Marx allowed us into their conversation as they discussed five cookbooks and their expectations as Jewish readers and eaters. This discussion has been edited for length.

—

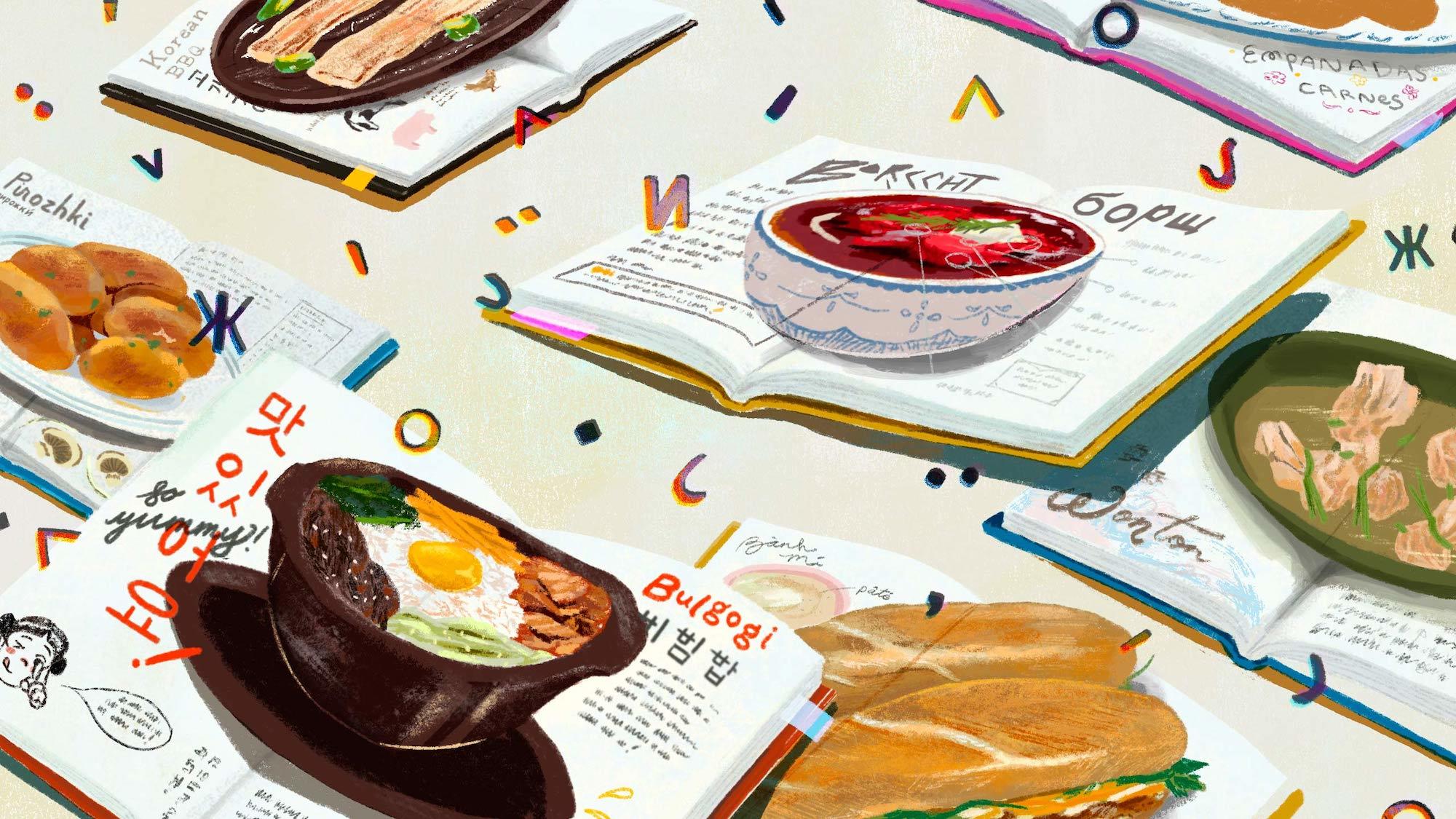

Druckman: With these cookbooks, I counted four different ways you can identify as Jewish. And they’re interconnected. It’s not just like one.

You can identify culturally. You can identify with it religiously, on a level of sacredness and belief. There’s also the question of ethnicity, which is related to culture, but that is its own pocket. And then finally, which I know you and I could talk about for hours, there’s the question of whether or not it’s a nationality. Like, do we all secretly think we’re Israeli, even though we’re American?

When I was looking at these cookbooks, I wanted to see how they engaged with any one of those identities. Most of them are basically just getting to the cultural part, the first part. There’s some sort of skirting around the religious aspect. It’s not easy to define Jewish food when it’s already not easy to define Jewishness, and everyone is looking at it very differently.

It’s not easy to define Jewish food when it’s already not easy to define Jewishness, and everyone is looking at it very differently.

Flint Marx: When you get any sort of diasporic cuisine, it’s like trying to herd cats. Borders shift. Chefs and culinary traditions oftentimes don’t really pay attention to shifting borders, where people are moving in the world. So it’s a very messy thing, which I think makes it exciting. But when you start to look at what Jewish food is through the prism of certain cookbooks, it can also be frustrating, enlightening, head-scratching.

Druckman: We should say that we’re not here to tell you whether or not you should buy these books. Or whether or not these recipes are well-tested or well-developed. Or whether or not we want to actually make the Everything Bagel Kugel. That’s not our purpose. We’re looking at them more as cultural objects—how these books reflect back ideas of Jewishness into the world in 2022. There’s been a spate of recently published books because there’s been heightened interest in Jewish food and Israeli food, which is interestingly not called Jewish food. It’s called Israeli food or else it’s just pegged as Middle Eastern—as though it represents all of that.

Flint Marx: That’s a dissertation.

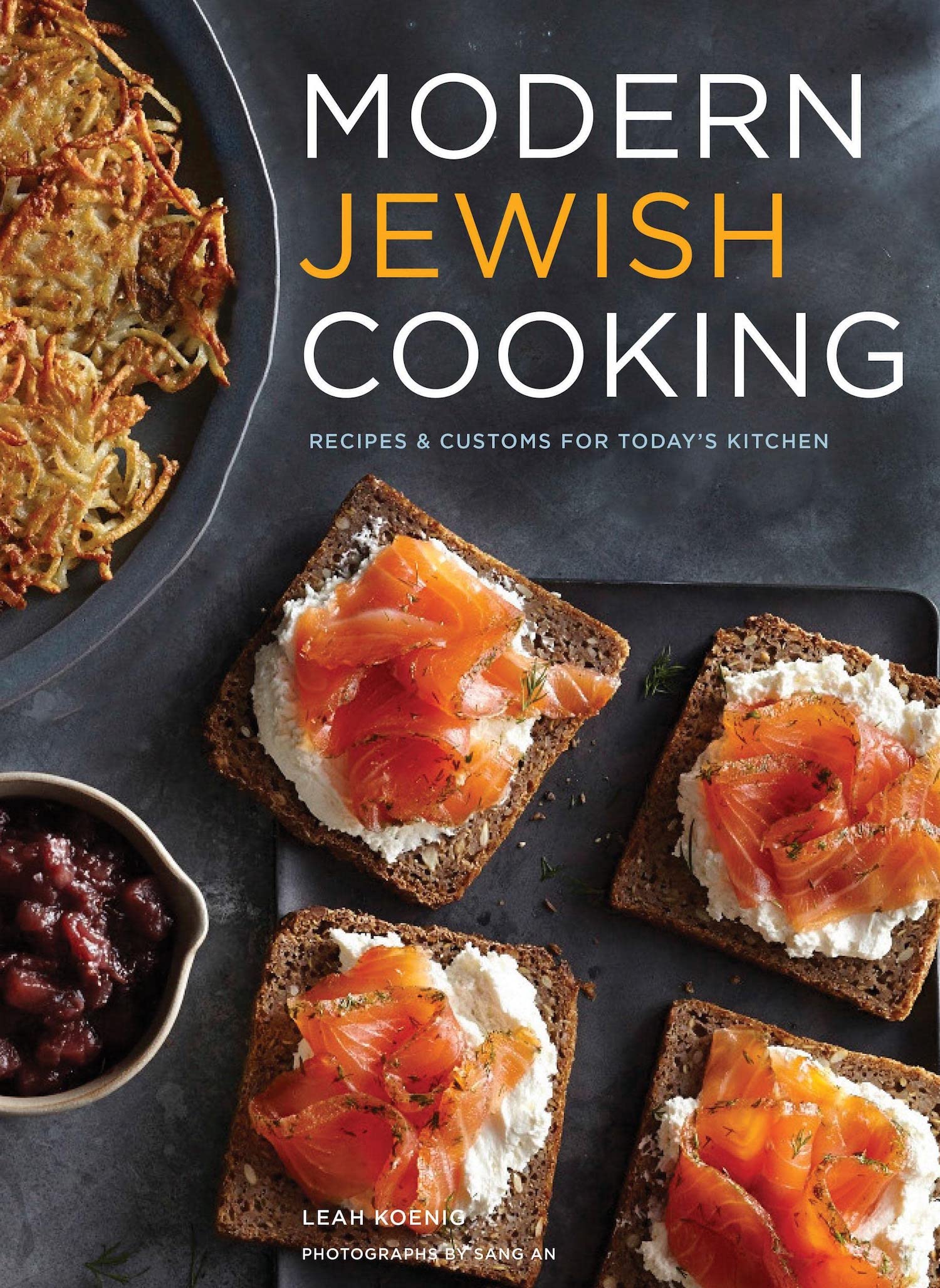

Druckman: The first book is Leah Koenig’s Modern Jewish Cooking. What year was that? 2015.

Courtesy of Chronicle Books

Flint Marx: I know we’re not doing product recommendations, but it’s aged well, in my opinion. So in 2015 or a few years earlier, we started to see this so-called renaissance or rebirth of traditional Jewish food, how to, say, make better gefilte fish and explore these Old World food traditions. The artisanal food movement in general took off, flourished, metastasized. And Jewish food got caught up in that. So you got this new generation of cooks and cookbook writers who were really interested in re-examining Jewish foods and using that same lens that people were putting on other cuisines that they wanted to quote unquote “modernize,” “elevate.”

Druckman: “Global” has become a sort of catchall now for this.

Flint Marx: When I first picked up this cookbook, I was really interested because it has the title Modern Jewish Cooking, and I was like, “Well, what does ‘modern’ actually mean here?” What is this going to tell us?” It did sort of bring in this idea of reinvention, but it wasn’t obnoxious about it. It wasn’t shticky. It’s restrained and elegant. And the recipes work. That’s a good thing to be able to say about any cookbook.

Druckman: I realized that “modern” was a nice euphemism for “assimilated.” And I don’t mean that as a bad thing, but assimilated into our American food culture. That’s across the board for all of the books we’re going to talk about today, I think, except maybe one.

They’re all looking at this from the distinct point of view of the American food landscape. And I kind of wish that that was stated explicitly; maybe I’m being a stickler. But when we’re talking about a diasporic cuisine, it’s nicer if the book can give it a little bit of a geographic focus just to anchor it. I really, really liked this cookbook because I did think it was balanced, and it was fair in terms of updating what we expect of certain ideas about Jewish food.

But as someone who is coming to these books wanting to learn more about the actual connection to Jewishness, I wish that they had given me more than just descriptions of the dish that I was about to cook. There’s never much of a statement about what makes these things Jewish. There’s like a fennel gratin, for example. And it looks delicious, [but] I’m looking at it and I’m thinking, “Well, what makes fennel gratin Jewish?”

Flint Marx: I think it’s food that can loosely be grouped as “It looks not out of place on a Sabbath table,” right? It’s food you can pass off as acceptable for a nice meal that might have some sort of ceremonial significance attached to it. But even as I’m saying that, I’m like, “Well, what food would that actually exclude? Who is the intended audience?”

It points to this overarching, really interesting question: How does a food become Jewish? I can’t answer that question. But this is the question on my mind when I look at this recipe of really nice-looking pan-roasted turnips. I certainly don’t object to it being there. I like that it’s there. If you’ve tasked yourself with making a quote unquote modern Jewish cookbook, you’re going to be looking for vegetable-forward recipes like turnips or fennel. It takes on the popular perception of Jewish food as being like, heavy and beige and outdated.

I realized that “modern” was a nice euphemism for “assimilated.” And I don’t mean that as a bad thing, but assimilated into our American food culture.

Druckman: Maybe I’m being annoying about this, but all they had to do in their headnote is say how it was a really nice way to round out a holiday meal. Also, there is this section about new Israeli cuisine going global. I wish she’d done it a little differently because it was presented as a trend. And it kind of lumped in Moroccan and Ethiopian food. I know and you know these Jewish populations are really different. I wish she could have teased that out.

Flint Marx: Overall, this is a book that makes me feel I’m reading something by a Jew who wants other people to know about Jewish food and have an appreciation for their traditions and culture behind it.

Druckman: I think it presumes that the readers are Jewish and that they probably know something about traditional Jewish food—so that they’re going to be in on the “joke,” you know what I mean? I just wish that some of that connection was made a bit stronger. Again, that’s my own bias. But for someone like me, where my knowledge of traditional Jewish food has come from being a writer and researching things, it’s not knowledge I naturally had.

Flint Marx: Yeah, totally. I think this book is more aimed at Jews than non-Jews. And I think that the tell is in the word “modern” because any Jew who picks up this book will know what that means. You’re not going to get the same heavy, stodgy recipes you’re probably expecting from a Jewish cookbook, which honestly, is really unfair. There’s a lot of Jewish cookbooks out there that completely disabuse that notion and do it very well.

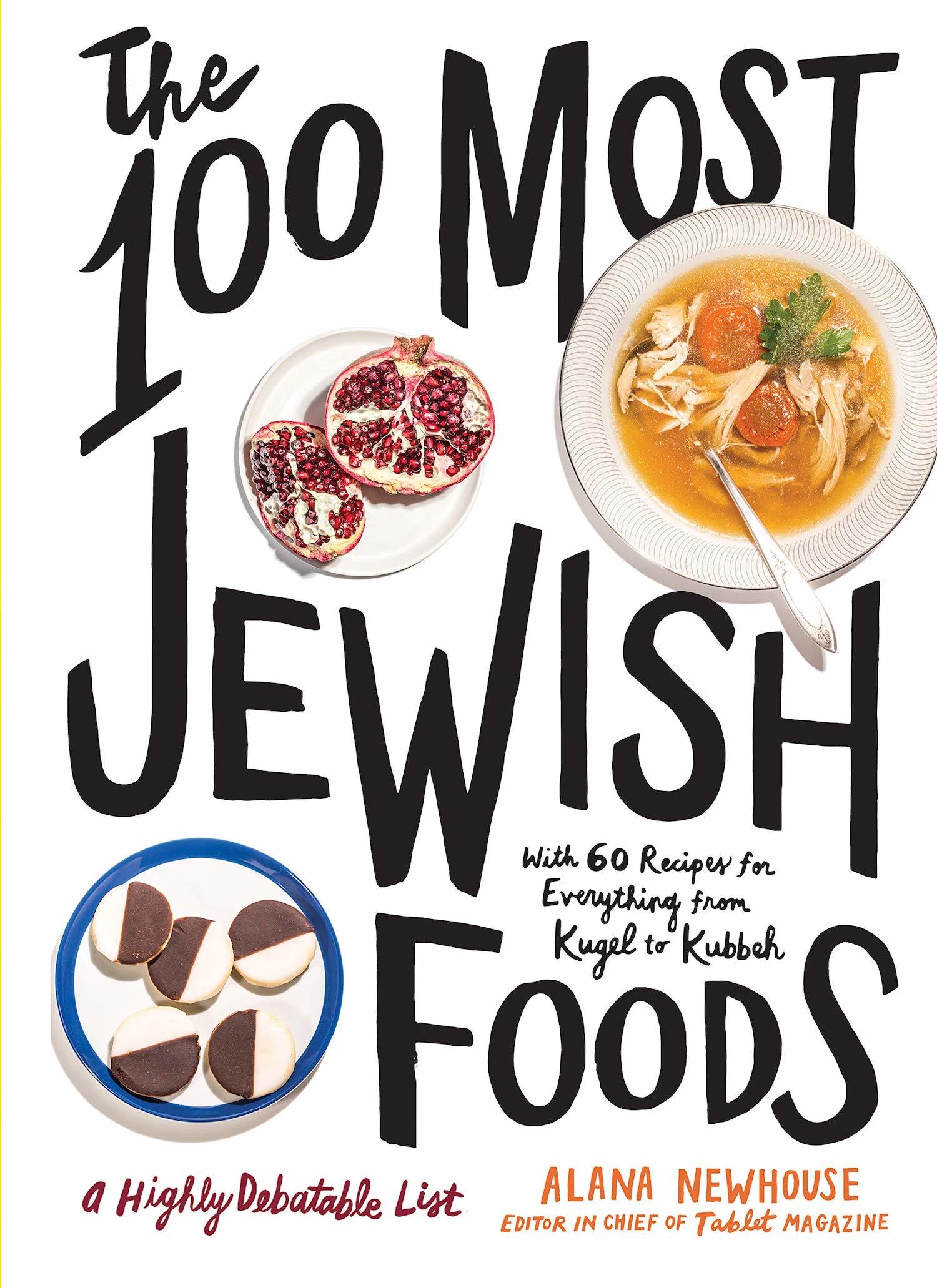

Druckman: So we are moving to The 100 Most Jewish Foods [by Alana Newhouse].

Courtesy of Artisan

Flint Marx: So a disclaimer: I was a recipe developer on this book, and I know at least one of the people who was very intricately involved with it.

Druckman: To what degree do you think of this book as a cookbook, having tested it versus objectively looking at it? Do you think people realize it’s a cookbook?

Flint Marx: I think it’s not a cookbook and not not a cookbook. How’s that for a non-answer? It’s true, though.

Certain people are going to come to this book because they want to read about, you know, culturally Jewish things. Honestly, even as somebody who developed recipes for this book, I personally don’t read it as a cookbook. I read it as a collection of really entertaining, often very thoughtful essays just about this whole question of what makes food Jewish. It forces you to engage with questions like: Why are we considering a used teabag Jewish?

And I appreciate that. I like that it’s argumentative and crotchety, which some would argue is also a very Jewish thing. So I appreciate it more from a philosophical standpoint than a practical cooking standpoint.

I read it as a collection of really entertaining, often very thoughtful essays just about this whole question of what makes food Jewish.

Druckman: Who do you think the audience for this book was? Because I am unclear. You think it’s Jewish.

Flint Marx: I think totally it’s for Jews and people who love them or live with one [laughing]. Because there’s all this Jewish shorthand.

Druckman: I understood very well what this book wants to do, and I liked that they clearly said there is no such thing as a definitive list of Jewish foods. Me being me, I’m like, “Well, then why do the book at all?” This also is a kind of a Jewish question. But that said, I don’t care to hear why Eric Ripert thinks gefilte fish is Jewish.

“People are coming to the concept of Jewishness with very different ideas, so the way one person writes about a product might be very deeply tied to a holiday or a renewal, while others may be talking about it in a completely secular way.” – Rebecca Flint Marx

MediaNews Group via Getty Images

Flint Marx: I kind of agree. He’s not Jewish?

Druckman: In no way. A Buddhist? My issue with this book was its need to package itself as a fun gift. My problem wasn’t so much which foods were chosen because that was always going to be debatable. The question was about who got to decide. There are a lot of people in this book where I was like, “Well, yes, that is someone who always writes about Jewish food or I know you.”

Flint Marx: I did really like it for the writing—it’s such a fun book to read. People are coming to the concept of Jewishness with very different ideas, so the way one person writes about a product might be very deeply tied to a holiday or a renewal, while others may be talking about it in a completely secular way. I think it’s representative of the range of experiences we all have.

I want to go back to something I said earlier when you asked “Who do you think this book is aimed at?” And I said Jews, and I do believe that. But to qualify that further, it’s like a specific slice of an American Jewish audience—people like me and you who grew up with cultural touchstones in certain communities and cultures. But you know, there are going to be other American Jews who look at this book and don’t have that connection.

Druckman: I do wonder if a deeply religious person would be offended. But I mean, a deeply religious person isn’t looking at these books. Orthodox people aren’t picking these cookbooks up.

I [often] read about how New York or like “New York Jew” is often code for “Jew.” When people think of a Jewish person like they’re often thinking of, like, Jerry Seinfeld. Maybe Mel Brooks or Jackie Mason or something. But there’s a certain kind of vibe that has been made synonymous with New York, even though it might not be said.

“When people think of a Jewish person like they’re often thinking of, like, Jerry Seinfeld. Maybe Mel Brooks or Jackie Mason or something. But there’s a certain kind of vibe that has been made synonymous with New York, even though it might not be said.” – Charlotte Druckman

Getty Images for Philly Fights Cancer

Flint Marx: It’s the Cranky New York Jew book. There’s so many neuroses threaded through it, which I personally like.

Druckman: Again, as a Jewish person looking for information about Jewish food, I feel like it’s the same few people writing about it over and over again. And unfortunately, they all kind of have the same point of view, which is an Eastern European kind of New York sensibility. What’s unfortunate is that they’ve kind of cornered the market. It would be nice to hear from Sephardic Jews, from more Arab Jews. It bugs me that the only Black Jewish food writer that we know about is Michael Twitty, for example. It becomes part of this sort of monolithic representation of Jewish food, and I would say almost monochromatic.

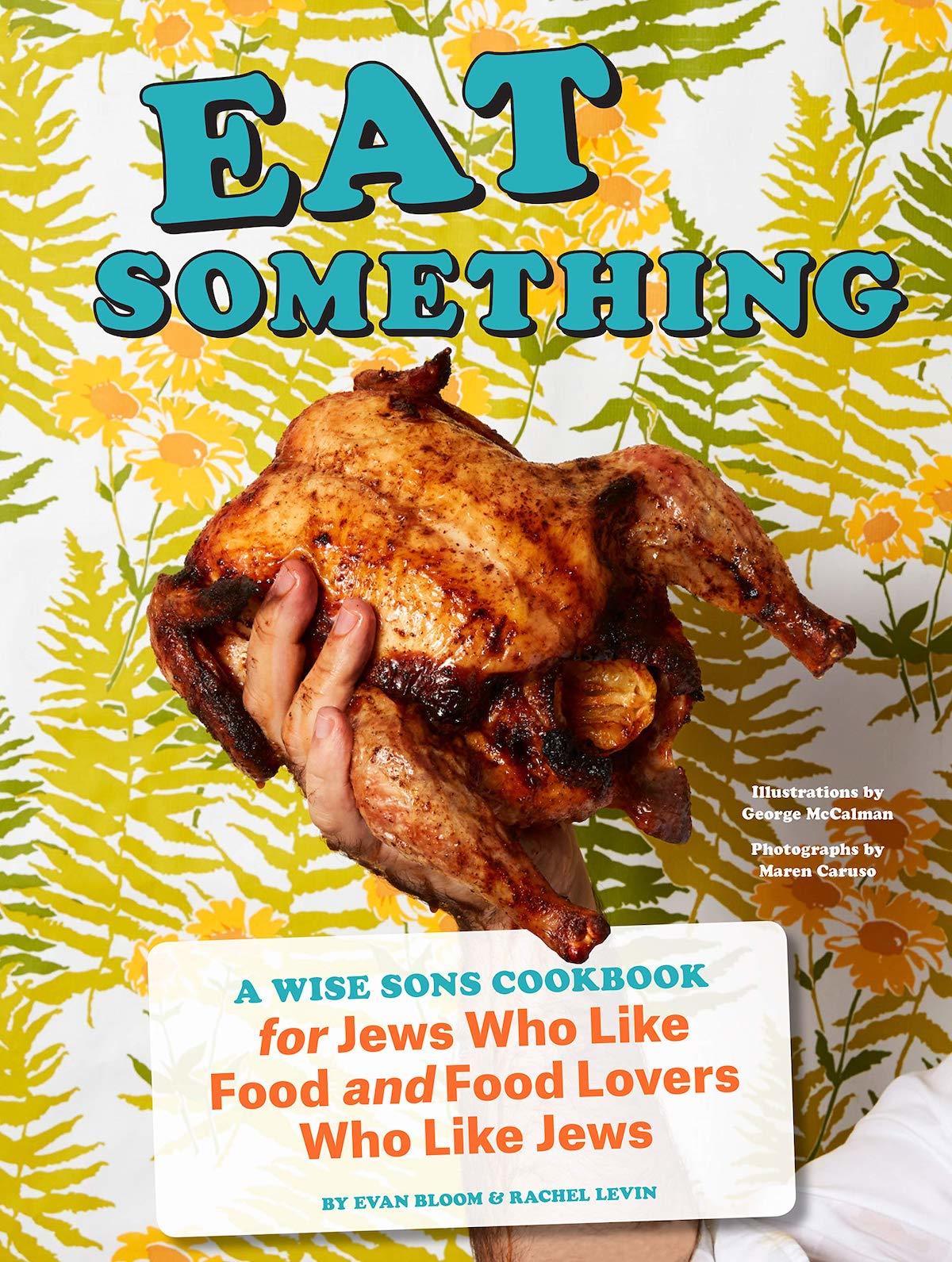

So Eat Something: A Wise Sons Cookbook for Jews Who Like Food and People Who Like Jews by Evan Bloom and Rachel Levin?

Flint Marx: Here’s the funny thing. We were talking so much about books being filtered through the lens of New York Jewishness. To me, this one has a very like, Florida and Northern California lens.

I feel like these books speak to a generational gap where we have people who are disconnected from their roots, like the disconnect from the immigrant part of their family that came here. Or it’s a disconnect from religious practice.

Druckman: I’m getting the Palm Beach or Boca Grandparent Vibe. I got a little annoyed at this book. Annoyed that we’re getting into high shtick. I wrote down that if we were giving the Hollywood pitch version of this book, it would be The Goldbergs, but it’s a cookbook.

Flint Marx: Mm-hmm. It’s a little borscht belt.

Druckman: But I feel like these books speak to a generational gap where we have people who are disconnected from their roots, like the disconnect from the immigrant part of their family that came here. Or it’s a disconnect from religious practice. But what I feel about cookbooks like this and the next one we’re going to talk about is that they’re operating off of a nostalgia for nostalgia. Instead of getting something that feels—I’m putting it in quotes—“real” or “authentic,” you get something that ends up seeming caricatured. But the actual experience or connections aren’t there. You’re missing something that your parents or grandparents had, and you’re trying to almost mimic their nostalgia for a thing they had and lost. You end up constructing something that feels forced.

I think that’s true of a lot of these cookbooks presenting this sort of rediscovery or reclamation of Jewish food. But it worries me you can end up inadvertently feeding stereotypes back to Jews. Like if this book is for “Jews who like food and food lovers who like Jews,” it comes dangerously close to stereotype. I also think it’s sort of dangerous when you’re talking about religious holidays and you’re trying to package it in an entertaining cookbook— it becomes really lifestyle-y.

Courtesy of Chronicle Books

Flint Marx: The way certain rituals are celebrated, the hallmarks, the cultural touchstones that they talk about a lot in this book, all to me seemed like it’s nostalgia for a specifically Gen-X childhood. I think one of the big inspirations for this cookbook was not a cookbook, but Bar Mitzvah Disco. It’s this sort of campy fun look back at like, your childhood bar mitzvah and what that looked like through photos.

Druckman: It’s good to be able to have a sense of humor about who we are all the time. But there is a fine line, when we’re talking about an actual cultural heritage.

I see how fun it was to do structurally and to create the voice. But then when I pick it up as an actual cookbook, it falls short of being effective as a place to learn about Jewish food. It’s possible that the reason that I’m sort of not getting it or that it seems like a sitcom to me, is that I didn’t grow up in the suburbs, right?

Flint Marx: I can identify more closely with the kind of Jewish experience they’re representing here. I grew up in a college town and what was, I suppose, a suburb within that town. I felt a longing reading this book. I think it was a longing for those big, really obnoxious, fun celebrations that revolved around food, where you end up kind of losing the meaning of whatever you’re ostensibly there to celebrate. What you’re getting is this sense of community. That was so important to me as somebody who grew up in an area that, well, we didn’t have no Jews, but we didn’t have a ton either.

When I moved to New York, it was a very different feeling to know that like everywhere you go, most likely you’re going to find somebody Jewish. And when I lived in San Francisco, which is where the authors of this book live, I had a hard time finding community. Not to say there wasn’t a community there, and maybe it’s where I was looking, but I didn’t experience a strong Jewish cultural connection there.

I felt a longing reading this book. I think it was a longing for those big, really obnoxious, fun celebrations that revolved around food, where you end up kind of losing the meaning of whatever you’re ostensibly there to celebrate.

Druckman: I wanted it to have a little more … gravitas isn’t the right word, but something that was anchoring it. On the other hand, I’m the last person who thinks a cookbook should be everything to all people. And if it has the effect that it’s intended to have, even just on you, then it nailed what it wanted to do.

Flint Marx: As my English professor said in freshman year of college, we all have baggage that we bring to whatever text we interact with, right? I look at this book and I’m like, “This feels familiar to me,” even though I didn’t grow up taking trips to Palm Beach or whatever. There is still that element of suburban Jewish life in the ’80s and ’90s that feels so familiar to me. And it makes me wish some of my relatives were still around, frankly.

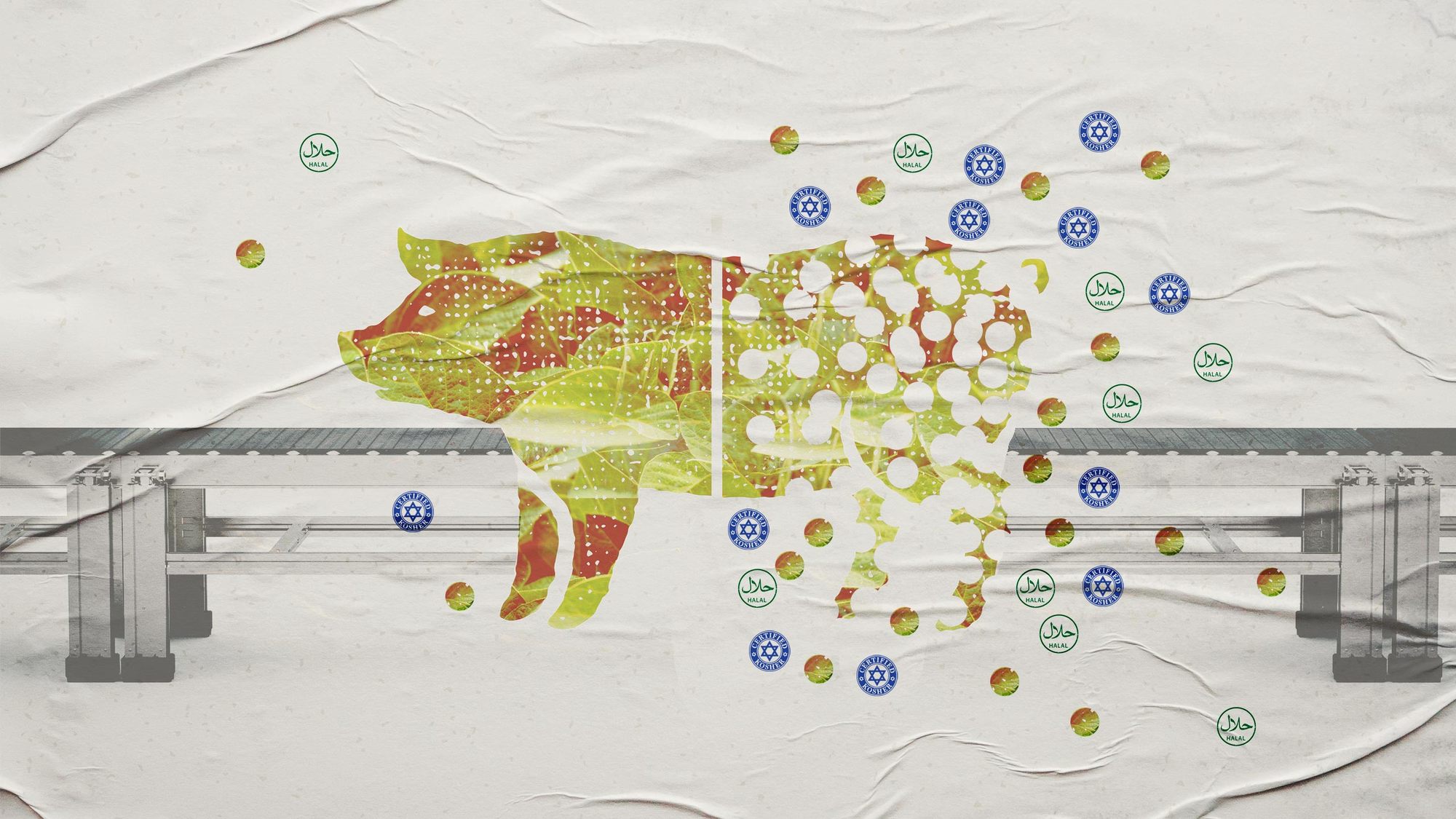

Druckman: Next is Jew-Ish by Jake Cohen. We should probably say that earlier this year, Jake Cohen was named as a defendant in a case about alleged discrimination at FeedFeed, the company where he worked. We did not know that when this story was first proposed. Neither of us looked at the book through that lens. So when we criticize this book—because we’re both very critical of this book—it is not related to issues outside of the book. It comes solely from having looked at the material.

This book really pissed me off.

Flint Marx: Yeah, me too. So the book, to be clear, is written as Jew hyphen ish. That title Jew-Ish, not Jewish, is billed as reinvented recipes from a “modern mensch.”

What pissed me off was this idea in the introduction, I’m paraphrasing, that if you’re not the kind of Jew who goes to synagogue, you are not fully Jewish, you are Jew-Ish. So already I’m kind of like, well, wait a minute because like, I don’t really go to temple. Does that mean I’m only sort of Jewish? Am I just a cultural Jew, a “less than”? This whole concept of varying degrees of what makes a Jew a Jew, told in this incredibly glib way, was really galling.

Druckman: And what made me even more annoyed was like he was saying, “We are not fully Jewish, but also you don’t have to do too much to be just like us and being just like us is really cool, so come join our party, right?” Incredibly reductive in so many ways. I felt like he was trying to offer himself up as the Alison Roman of Jewish cooking. This was a book about entertaining, where he was saying that you don’t have to know anything about Shabbat, but if you throw dinner parties every Friday night, you can be Jewish like me.

It also felt prescriptive, like he was saying that was the better way to be Jewish, that we should aspire to not necessarily feeling connected in any way, besides throwing Friday night dinner parties. Either way, if that’s what makes you feel Jewish, I’m not going to judge it. But I don’t think you should actually go around telling people that this is how to do it or how to be any degree of Jewish. My mind was kind of blown by it.

“There is something so elegant about making it about Shabbat throughout the year because that allowed it to be seasonal. I loved that she was able to get at this idea of repetition and where things came from in terms of religious practice and then how they spread.” – Charlotte Druckman

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Flint Marx: To be fair, I wouldn’t say that Jake Cohen is saying, you know, no Jewish anything. But I think I know what you’re saying: this idea of selective parts of Judaism as an aspirational lifestyle, that all you need to do is throw tahini on something and “Oh my God, it’s Jewish.”

Druckman: It’s like he’s selling Judaism as a lifestyle brand. And part of that brand means being minimally connected to actually being Jewish. These things are so decontextualized.

Flint Marx: Yeah, I think that’s a good way of putting it. It’s like a very decontextualized Jewish cookbook.

I think one of the recipes that really irked me was that tomato galette with everything bagel seasoning sprinkled on the crust, that was one of them. And the whole pumpkin spice babka thing.

Druckman: Oh lord.

Flint Marx: Look, I’m not a purist. I think the whole notion of authenticity is a trap. It’s impossible. And I think that the more people try to contort themselves into some prescribed idea of authenticity, we all lose from that. There’s nothing to be gained.

But having said that, I think there is something that really pissed me off about somebody taking a babka and being like, “Let’s put pumpkin spice on it” because … what? What is your goal here? You have this whole thing of reinventing recipes. To what end are you trying to make babka more fun? Babka’s already fun. It’s fucking chocolate and dough. What is more fun than that?

Look, this is a book for entertaining. I don’t have a problem with that. I like food that is designed to serve a bunch of people. That’s cool, but make it just an entertaining book. Just call it like 60 Sexy Sabbaths.

You can’t brand Jewishness, or you shouldn’t try. It’s a mess.

Druckman: Make it an entertaining cookbook. Just explain that you are someone who is not really a religious Jewish person, but has found a lot of comfort and inspiration in Jewish food. And you’ve been looking at food trends and applying that to Jewish food, because that’s how you like to entertain. That’s totally fine. But you don’t have to market it as some formula for being Jewish. You can’t brand Jewishness, or you shouldn’t try. It’s a mess.

Flint Marx: Yeah. Please don’t.

Flint Marx: Everybody has to come to Judaism in their own time if they’re going to come, and there’s no right or wrong way to do it. If Jake Cohen started going to Sabbath dinners or throwing them and felt a sense of kinship and appreciation for his heritage, I’m not going to knock that. But whether it translates to being a meaningful cookbook is a completely different story.

Druckman: On the one hand, that is on him. But it’s also on publishers or a cookbook editor. I would not take it upon myself to write a Jewish cookbook. I do not have any business doing it. The only way I could do it would be if I spent a very long time doing research, but I could not write a personal Jewish cookbook because I did not grow up having any of these Jewish traditional foods and I don’t feel well-versed in them. So throwing pumpkin spice onto things is not going to help my cause.

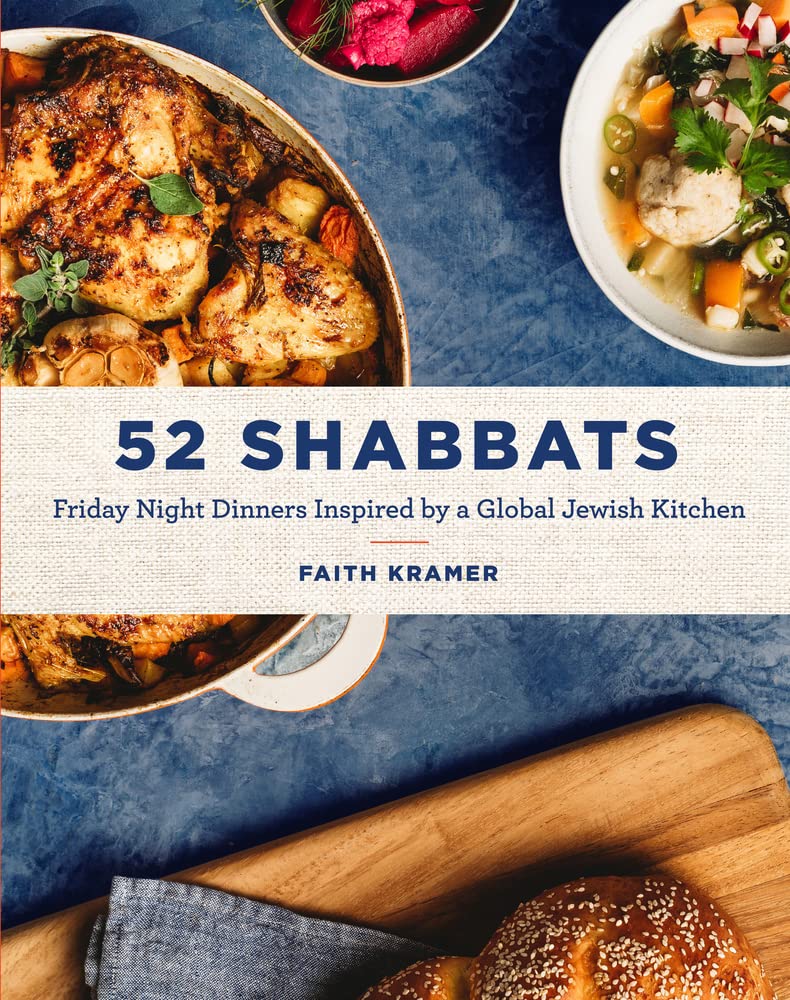

Our next book: Faith Kramer’s 52 Shabbats. It came out in December. It is actually a really lovely way to present the idea of what Shabbat is, as opposed to a totally decontextualized dinner party book.

I really liked 52 Shabbats. I would cook the most from Leah’s, but in terms of things I’m looking for in a cookbook about Jewish food or a Jewish experience, I really appreciated Faith Kramer’s 52. And I didn’t grow up having Shabbat.

Courtesy of The Collective Book Studio

Flint Marx: I did, in terms of there’d be a challah and a cup of Manischewitz on the table. But I don’t do this as an adult at all. One thing that I really enjoyed and appreciated about this book was the idea of diasporic cuisine and there being Jewish communities all over the world. This book really gets into that, and so much of what I appreciated about it was Faith Kramer’s willingness to really take the time to be like, here’s something you should know about how Jews in different countries celebrate the Sabbath or why certain foods have significance to certain people and in these traditions.

Druckman: It felt responsible. I felt like this was someone who is taking a more journalistic approach, and that sense of really trying to convey where things came from. I really liked how she would do recipes for this same main ingredient, but with very different treatments back to back. Salmon might be cooked one way in one part of the world by one Jew and another way by another Jew in another part of the world.

I also thought this was probably the book that most seamlessly integrated religion and ritual. There is something so elegant about making it about Shabbat throughout the year because that allowed it to be seasonal. I loved that she was able to get at this idea of repetition and where things came from in terms of religious practice and then how they spread. Again, all of these books have a certain European Jewish-centricity to them. But this one felt the most aware of that, the most removed from it.

I thought it really showed you, especially after the Holocaust and modern political shifts, how migration works. And it also made you understand, without having to hit you over the head with it, that fusion is a defining quality of Jewish cuisine.

What’s amazing with all the different sorts of migrations is that people end up coming almost full circle. So you’ll see that there was a community that moved to the other side of the world, and then some of them ended up going back. There’s a whole double cultural exchange happening geographically. That’s really cool.

Flint Marx: Along those lines, one of the things that really stuck with me about this book was how, when she talks about Jewish communities around the world, she’ll give you numbers. Like this many thousands of Jews once lived in Shanghai, for example, but by the year 2017, only 2,500 were left. So it’s almost like watching waves go back and forth across the planet. You see people go where geopolitical events carry them.

Druckman: In the meantime, if you didn’t want to get all of that depth of knowledge from this book, you could treat it as a really functional, entertaining cookbook. I actually pulled out an example of the comparative ingredient thing. There are two lentil recipes back to back. One is sweet and tart: roasted carrots with lentils. And then the next page is Berber lentils with cauliflower. But one was more of a sweet and sour, one was earthier. Reminded you where Jews have lived.

Flint Marx: That’s the thing. Something that people talk about when they talk about how cookbooks function: Is there a conversation going on between the various recipes in a cookbook? This book is very rich for that reason. I have not actually cooked out of this book. Yet as a book to read, I found myself completely absorbed, which is not something I normally say about most cookbooks.