Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting

“When you have to turn to that type of lending, it means that there’s a certain degree of desperation out there.”

The Trump Administration has paid farmers billions to offset losses from ongoing trade wars, but millions have also gone to an alternative farm lender.

Agrifund LLC, which does business as Ag Resource Management, or ARM, has received more trade mitigation money than anyone else, according to a Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture data. Through almost two years of payments, the total is about $75 million.

Under USDA rules, farmers can assign government payments they’re eligible for to third parties. If a producer has debt with ARM, it’s required.

This article is republished from The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting. Read the original article here.

Government payments go toward paying down any outstanding debt a farmer has with ARM until it’s paid off, said Billy Moore, the company’s spokesman. It’s written into their contracts, he said.

ARM is an industry-termed “alternative lender” because it is lightly regulated, it generally charges higher interest rates than traditional lenders, and farmers face fewer obstacles to getting the loans. During recent congressional testimony, bankers and other creditors said they’ve seen more and more farmers turn to alternative lenders recently.

The development of turning to riskier loans shows how desperate some farmers have gotten to stay in operation, said Glen Smith, the chairman and chief executive officer of the Farm Credit Administration, which regulates some agricultural lenders.

“It’s a symptom of stressed economic times when those types of lenders emerge,” he said. “When you have to turn to that type of lending, it means that there’s a certain degree of desperation out there.”

In November, the Wall Street Journal reported that ARM’s loan volume, over the past three years, had increased at a 40 percent rate. The trade wars have been one of a few factors in the company’s growth, Moore told the Midwest Center.

He said ARM provides a valuable service to farmers. Many farmers don’t have the equity—such as land or equipment—typically required by banks to get a loan, he said. ARM is different because it doesn’t rely on equity.

“We look more at their ability to produce [a crop],” he said. “We’ve expanded our footprint because the market is there and the need is there.”

If farmers do have loans with traditional lenders, the extra debt from an alternative loan may affect their ability to pay back their other debt.

ARM offers operating loans that mature in less than a year, Moore said. The interest rates it offers vary but are typically higher than banks, he said. The Wall Street Journal reported ARM charged interest rates of about 8 percent. Moore didn’t want to specifically say what his company’s rates were, but he said the rates could be higher than what the paper reported. More traditional lenders offer interest rates between 4 to 6 percent, Smith said.

Based in Texas, ARM has offices in the Midwest, the South and Texas. In a press release, it said it aims to bring “Wall Street financial solutions to rural America.”

The American Farm Bureau Federation’s policies on creditors states that farmers, to meet their financial needs, require “a variety of credit sources at the lowest possible interest rates,” Gary Joiner, the Texas Farm Bureau’s spokesperson, said in an email.

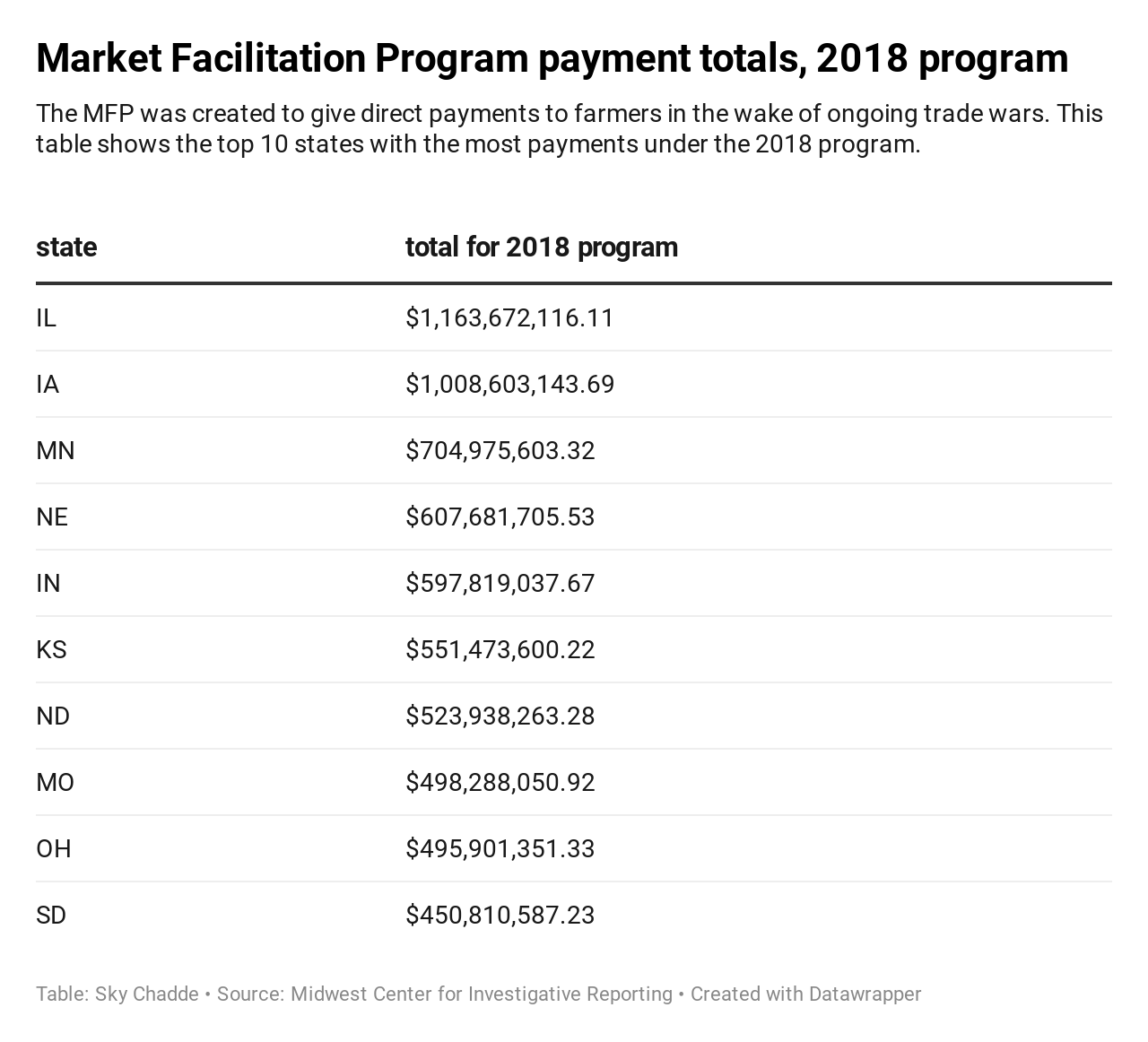

The Market Facilitation Program was created to help farmers affected by the Trump Administration’s trade wars by giving them direct payments, but difficult economic conditions in the Midwest persist.

This year, the share of loans with “major” or “severe” repayment problems hit a 20-year high, according to a survey released in August by the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, which examines economies in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan and Wisconsin.

In November, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, which includes Missouri and Nebraska, reported loan repayment rates were declining.

Through October 2019, about $9 billion in payments have been disbursed under the 2018 market facilitation program, and about $6.5 billion has been disbursed under the 2019 program, according to the USDA data. Up to $14.5 billion could be disbursed under the 2019 program.

The large majority of market facilitation payments have gone straight to farmers, according to the analysis of the data. Banks and members of the Farm Credit System, regulated by the Farm Credit Administration, have also received payments.

But, by far, ARM has received the most money under the program, according to the Midwest Center’s analysis of USDA payment data.

Under the 2018 trade mitigation program, ARM has received about $35 million. Under the 2019 program, it has received about $40 million, for a two-year total of about $75 million.

Market facilitation has been the most lucrative program for ARM. During the same time period, it received about $110 million total from all USDA’s Farm Service Agency payment programs, including trade mitigation, according to the analysis.

“It’s a symptom of stressed economic times when those types of lenders emerge.”

“The company with the second-highest amount from the trade mitigation program—AgCountry Farm Credit Services, a regulated lender in the Midwest—has received about $37 million for the two years combined, according to the analysis.

(The program has limits on how much money a single entity can receive, but it appears to not apply to third-parties that have been assigned the payment.)

The Midwest Center could only identify two other alternative lenders that had received market facilitation payments. They received much less than ARM—one has received about $7.5 million total, and the other about $1 million total.

Farmers pursue alternative loan options because they’ve borrowed “up to the hilt” and need an additional source of income to keep their operation going, said Alex White, a professor at Virginia Tech University who focuses on farm economics.

These loans are typically easier to get than traditional ones, and the influx of cash would, presumably, get producers through until their situation improves, he said.

With extreme weather increasing throughout the Midwest, farmers have struggled to produce a reliable crop.

That’s led some traditional lenders to avoid taking on the risk of lending to them, said Paul Erickson, the president and CEO of Conterra Ag, an Iowa-based lender that focuses on restructuring real estate debt. His company has worked with ARM, he said.

When it comes to the ability to access more traditional credit, “rural America has been left behind,” he said. “A lot of small family farms will be lost without ARM or Conterra.”

If farmers do have loans with traditional lenders, the extra debt from an alternative loan may affect their ability to pay back their other debt, Shan Hanes, the president and CEO of Heartland Tri-State Bank in Kansas told a congressional committee in December.

“It’s that one extra straw that broke the camel’s back,” he said. “Then, they come to us and they can’t figure out why they didn’t break even.”

Any farmer that takes on debt from alternative lenders should have an exit plan, said Mark Scanlan, the senior vice president for agriculture and rural policy at the Independent Community Bankers Association.

“They should still get advice outside of that non-traditional lender, just to be sure,” he said, “to be sure what they’re doing is wise.”

The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting is a nonprofit, online newsroom offering investigative and enterprise coverage of agribusiness, Big Ag and related issues through data analysis, visualizations, in-depth reports and interactive web tools. Visit us online at www.investigatemidwest.org/

Sky Chadde is the Midwest Center’s Gannett Agricultural Data Fellow. Lucille Sherman is a Gannett Data and Investigations reporter.

Pramod Acharya contributed to this story.